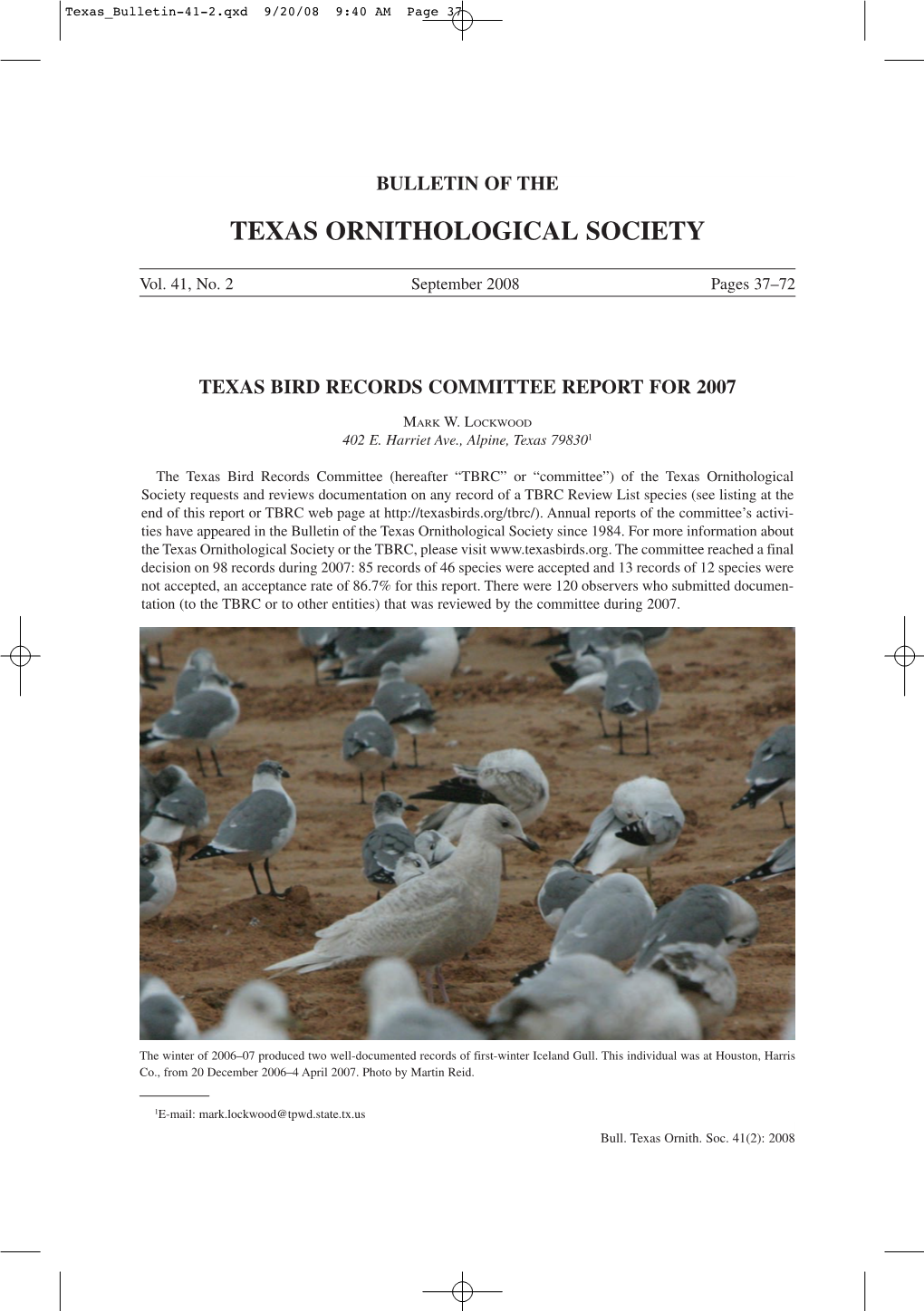

Bulletin Vol. 41, No. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antbird Guilds in the Lowland Caribbean Rainforest of Southeast Nicaragua1

The Condor 102:7X4-794 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 2000 ANTBIRD GUILDS IN THE LOWLAND CARIBBEAN RAINFOREST OF SOUTHEAST NICARAGUA1 MARTIN L. CODY Department of OrganismicBiology, Ecology and Evolution, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1606, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Some 20 speciesof antbirdsoccur in lowland Caribbeanrainforest in southeast Nicaragua where they form five distinct guilds on the basis of habitat preferences,foraging ecology, and foraging behavior. Three guilds are habitat-based,in Edge, Forest, and Gaps within forest; two are behaviorally distinct, with species of army ant followers and those foraging within mixed-species flocks. The guilds each contain 3-6 antbird species. Within guilds, species are segregatedby body size differences between member species, and in several guilds are evenly spaced on a logarithmic scale of body mass. Among guilds, the factors by which adjacent body sizes differ vary between 1.25 and 1.75. Body size differ- ences may be related to differences in preferred prey sizes, but are influenced also by the density of the vegetation in which each speciescustomarily forages. Resumen. Unas 20 especies de aves hormiguerasviven en el bosque tropical perenni- folio, surestede Nicaragua, donde se forman cinquo gremios distinctos estribando en pre- ferencias de habitat, ecologia y comportamiento de las costumbresde alimentacion. Las diferenciasentre las varias especiesson cuantificadaspor caractaristicasde1 ambiente vegetal y por la ecologia y comportamientode la alimentaci6n, y usadospara definir cinco grupos o gremios (“guilds”). Tres gremios se designanpor las relacionesde habitat: edge (margen), forest (selva), y gaps (aberturasadentro la selva); dos mas por comportamiento,partidarios de army ants (hormigasarmadas) y mixed-speciesflocks (forrejando en bandadasde especies mexcladas). -

A Comprehensive Multilocus Phylogeny of the Neotropical Cotingas

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 81 (2014) 120–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A comprehensive multilocus phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae, Aves) with a comparative evolutionary analysis of breeding system and plumage dimorphism and a revised phylogenetic classification ⇑ Jacob S. Berv 1, Richard O. Prum Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208105, New Haven, CT 06520, USA article info abstract Article history: The Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae: Aves) are a group of passerine birds that are characterized by Received 18 April 2014 extreme diversity in morphology, ecology, breeding system, and behavior. Here, we present a compre- Revised 24 July 2014 hensive phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas based on six nuclear and mitochondrial loci (7500 bp) Accepted 6 September 2014 for a sample of 61 cotinga species in all 25 genera, and 22 species of suboscine outgroups. Our taxon sam- Available online 16 September 2014 ple more than doubles the number of cotinga species studied in previous analyses, and allows us to test the monophyly of the cotingas as well as their intrageneric relationships with high resolution. We ana- Keywords: lyze our genetic data using a Bayesian species tree method, and concatenated Bayesian and maximum Phylogenetics likelihood methods, and present a highly supported phylogenetic hypothesis. We confirm the monophyly Bayesian inference Species-tree of the cotingas, and present the first phylogenetic evidence for the relationships of Phibalura flavirostris as Sexual selection the sister group to Ampelion and Doliornis, and the paraphyly of Lipaugus with respect to Tijuca. -

Belize), and Distribution in Yucatan

University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland Institut of Zoology Ecology of the Black Catbird, Melanoptila glabrirostris, at Shipstern Nature Reserve (Belize), and distribution in Yucatan. J.Laesser Annick Morgenthaler May 2003 Master thesis supervised by Prof. Claude Mermod and Dr. Louis-Félix Bersier CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1. Aim and description of the study 2. Geographic setting 2.1. Yucatan peninsula 2.2. Belize 2.3. Shipstern Nature Reserve 2.3.1. History and previous studies 2.3.2. Climate 2.3.3. Geology and soils 2.3.4. Vegetation 2.3.5. Fauna 3. The Black Catbird 3.1. Taxonomy 3.2. Description 3.3. Breeding 3.4. Ecology and biology 3.5. Distribution and threats 3.6. Current protection measures FIRST PART: BIOLOGY, HABITAT AND DENSITY AT SHIPSTERN 4. Materials and methods 4.1. Census 4.1.1. Territory mapping 4.1.2. Transect point-count 4.2. Sizing and ringing 4.3. Nest survey (from hide) 5. Results 5.1. Biology 5.1.1. Morphometry 5.1.2. Nesting 5.1.3. Diet 5.1.4. Competition and predation 5.2. Habitat use and population density 5.2.1. Population density 5.2.2. Habitat use 5.2.3. Banded individuals monitoring 5.2.4. Distribution through the Reserve 6. Discussion 6.1. Biology 6.2. Habitat use and population density SECOND PART: DISTRIBUTION AND HABITATS THROUGHOUT THE RANGE 7. Materials and methods 7.1. Data collection 7.2. Visit to others sites 8. Results 8.1. Data compilation 8.2. Visited places 8.2.1. Corozalito (south of Shipstern lagoon) 8.2.2. -

Boc1282-080509:BOC Bulletin.Qxd

boc1282-080509:BOC Bulletin 5/9/2008 7:22 AM Page 107 Andrew Whittaker 107 Bull. B.O.C. 2008 128(2) Field evidence for the validity of White- tailed Tityra Tityra leucura Pelzeln, 1868 by Andrew Whittaker Received 30 March 2007; final revision received 28 February 2008 Tityra leucura (White- tailed Tityra) was described by Pelzeln (1868) from a specimen collected by J. Natterer, on 8 October 1829, at Salto do Girao [=Salto do Jirau] (09º20’S, 64º43’W) c.120 km south- west of Porto Velho, the capital of Rondônia, in south- central Amazonian Brazil (Fig 1). The holotype is an immature male and is housed in Vienna, at the Naturhistorisches Museum Wien (NMW 16.999). Subsequent authors (Hellmayr 1910, 1929, Pinto 1944, Peters 1979, Ridgely & Tudor 1994, Fitzpatrick 2004, Mallet- Rodrigues 2005) have expressed severe doubts concerning this taxon’s validity, whilst others simply chose to ignore it (Sick 1985, 1993, 1997, Collar et al. 1992.). Almost 180 years have passed since its collection with the result that T. leucura has slipped into oblivion, and the majority of Neotropical ornithologists and birdwatchers are unaware of its existence. Here, I review the history of T. leucura and then describe its rediscovery from the rio Madeira drainage of south- central Amazonian Brazil, providing details of my field observa- tions of an adult male. I present the first published photographs of the holotype of T. leucura, and compare plumage and morphological differences with two similar races of Black- crowned Tityra T. inquisitor pelzelni and T. i. albitorques. T. inquisitor specimens were examined at two Brazilian museums for abnormal plumage characters. -

Predation on Vertebrates by Neotropical Passerine Birds Leonardo E

Lundiana 6(1):57-66, 2005 © 2005 Instituto de Ciências Biológicas - UFMG ISSN 1676-6180 Predation on vertebrates by Neotropical passerine birds Leonardo E. Lopes1,2, Alexandre M. Fernandes1,3 & Miguel Â. Marini1,4 1 Depto. de Biologia Geral, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 31270-910, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 2 Current address: Lab. de Ornitologia, Depto. de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, 31270-910, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected]. 3 Current address: Coleções Zoológicas, Aves, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Avenida André Araújo, 2936, INPA II, 69083-000, Manaus, AM, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected]. 4 Current address: Lab. de Ornitologia, Depto. de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade de Brasília, 70910-900, Brasília, DF, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We investigated if passerine birds act as important predators of small vertebrates within the Neotropics. We surveyed published studies on bird diets, and information on labels of museum specimens, compiling data on the contents of 5,221 stomachs. Eighteen samples (0.3%) presented evidence of predation on vertebrates. Our bibliographic survey also provided records of 203 passerine species preying upon vertebrates, mainly frogs and lizards. Our data suggest that vertebrate predation by passerines is relatively uncommon in the Neotropics and not characteristic of any family. On the other hand, although rare, the ability to prey on vertebrates seems to be widely distributed among Neotropical passerines, which may respond opportunistically to the stimulus of a potential food item. -

AOS) Committee on Classification and Nomenclature: North and Middle America (NACC) 3 June 2020

American Ornithological Society (AOS) Committee on Classification and Nomenclature: North and Middle America (NACC) 3 June 2020 Guidelines for English bird names The American Ornithological Society’s North American Classification Committee (NACC) has long held responsibility for arbitrating the official names of birds that occur within its area of geographic coverage. Scientific names used are in accordance with the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN 1999); the committee has no discretion to modify scientific names that adhere to ICZN rules. English names for species are developed and maintained in keeping with the following guidelines, which are used when forming English names for new or recently split species and when considering proposals to change established names for previously known species: A. Principles and Procedures 1. Stability of English names. The NACC recognizes that there are substantial benefits to nomenclatural stability and that long-established English names should only be changed after careful deliberation and for good cause. As detailed in AOU (1983), NACC policy is to “retain well established names for well-known and widely distributed species, even if the group name or a modifier is not precisely accurate, universally appropriate, or descriptively the best possible.” The NACC has long interpreted this policy as a caution against the ever-present temptation to ‘improve’ well-established English names and this remains an important principle. In practice, this means that proposals to the NACC advocating a change to a long-established English name must present a strongly compelling, well-researched, and balanced rationale. 2. Name change procedures. The NACC process of considering an English name change is the same as for other nomenclatural topics. -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

Avian Monitoring Program

AVIAN INVENTORY AND MONITORING REPORT OSA CONSERVATION PROPERTIES CERRO OSA PIRO NEENAH PAPER OSA PENINSULA, COSTA RICA PREPARED BY: KAREN M. LEAVELLE FOR: OSA CONSERVATION APRIL 2013 Scarlet Macaw © Alan Dahl TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 3 Study Site 3 Bird Surveys 5 RESULTS Community Composition and Density 6 Neotropical Migratory and Indicator Species 6 Habitat and Elevation Associations Neenah Paper 12 LITERATURE CITED 14 Table 1: Osa Priority Species 3 Table 2: Species Richness 6 Table 3: Cumulative list of resident bird species 7 Table 4: Cumulative list of Neotropical migratory birds 10 Table 5: BCAT by elevation 11 Table 6: BCAT by forest type 12 Table 7: Neenah Paper species richness 12 Appendix A: Bird species densities Osa Conservation 15 Appendix B: Bird species densities Neenah Paper 16 Appendix C: Threatened or endemic species 17 Appendix D: Comprehensive list of all OC bird species 18 Appendix E: Comprehensive list of all Osa Peninsula species 24 RECOMMENDED CITATION Leavelle, K.M. 2013. Avian Inventory and Monitoring Report for Osa Conservation Properties at Cerro Osa and Piro Research Stations, Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. Technical Report for Osa Conservation. p 36. Washington, DC. INTRODUCTION The Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica is home to over 460 tropical year round resident and overwintering neotropical migratory bird species blanketing one of the most biologically diverse corners of the planet. The Osa habors eight regional endemic species, five of which are considered to be globally threatened or endangered (Appendix C), and over 100 North American Nearctic or passage migrants found within all 13 ecosystems that characterize the peninsula. -

Caye Caulker Forest and Marine Reserve

Caye Caulker Forest and Marine Reserve- Integrated Management Plan 2004-2009 *** Prepared For Belize Coastal Zone Management Institute/Authority and Belize Fisheries Department By Ellen M McRae, Consultant, CZMA/I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 LIST OF TABLES 8 LIST OF MAPS 9 LIST OF ACRONYMS 10 1. INTRODUCTION 12 1.1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION 12 1.1.1 Habitat Suitability—Rationale for Area’s Selection 12 1.1.2 History of Caye Caulker’s Protected Areas 14 1.1.3 Current Status 15 1.1.4 Legislative Authority 15 1.1.5 Context 17 1.2 GENERAL INFORMATION 17 1.2.1 Purpose and Scope of Plan 17 1.2.2 Location 18 1.2.3 Access 19 1.2.4 Land Tenure and Seabed Use 19 1.2.5 Graphic Representation 20 1.2.5.1 Mapping 20 1.2.5.2 Aerial Photographic and Satellite Imagery 20 1.2.5.3 Other Remote Imagery 21 2 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT 21 2.1 GEOLOGY, SUBSTRATE AND BATHYMETRY 21 2.2 HYDROLOGY 22 2.3 TIDES AND CURRENTS 23 2.4 WATER QUALITY 23 2.4.1 Seawater 23 2.4.2 Groundwater and Surface Waters on the Caye 24 2.5 CLIMATE AND WEATHER 25 2.5.1 General Climate Regime 26 2.5.2 Rainfall 26 2.5.3 Extreme Weather Events 26 3 BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT 29 3.1 EMERGENT SYSTEMS 29 3.1.1 Littoral Forest 29 3.1.1.1 Flora 31 3.1.1.2 Fauna 33 3.1.1.3 Commercially Harvested Species 36 3.1.1.4 Rare, Threatened and Endangered Species 37 3.1.1.5 Threats to Systems 38 3.1.2 Mangroves 39 3.1.2.1 Flora 40 3.1.2.2 Fauna 40 3.1.2.3 Commercially Harvested Species 42 3.1.2.4 Rare, Threatened and Endangered Species 43 3.1.2.5 Threats to System 44 3.2 SUBMERGED SYSTEMS 45 3.2.1 Seagrass and Other Lagoon -

Environmental Impact Assessment

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT For ARA MACAO Resort & Marina To be located in: Placencia, Stann Creek District Prepared by: Volume 1 January 2006 Table of Contents 1.0 Project Description & Layout Plan 1-1 1.01 Project Location and Description 1-1 1.02 The Physical Development Plans and the Description of the Facilities. 1-2 1.03 Plan Layout 1-5 1.04 Specifications for the Facilities and Forecast of Activities 1-7 1.05 Phases of Project Implementation 1-7 2.0 The Physical Environment 2-1 2.01 Topography 2-1 2.02 Climate 2-5 2.03 Geology 2-6 2.2 Project Facilities 2-10 3.0 Policy and Legal Administrative Framework 3-1 3.1 Policy 3-1 3.2 Legal Framework 3-2 3.3 Administrative Framework 3-4 3.4 The EIA Process 3-6 3.5 Permits and approvals required by the project 3-7 3.6 International And Regional Environmental Agreements 3-8 4.0 Flora and Fauna 4-1 4.1 Introduction 4-1 4.1.1 Mangrove Swamp 4-1 4.1.2 Freshwater Marsh and Swamps 4-1 4.1.3 Transitional Low Broadleaf Forest 4-1 4.2 Flora Survey 4-2 4.3 Avifaunal Survey 4-6 4.3.1 Results of bird census 4-6 4.4 Species of Key Conservation Concern 4-10 4.4.1 Reptiles 4-10 4.4.1.1 Crocodiles (Family Crocodylidae) 4-10 4.4.1.2 Spiny Tailed Iguana 4-11 4.4.1.3 Boa Constrictor 4-11 4.4.1.4 Mammals 4-11 4.5 Estimated Alteration of Vegetation 4-12 4.6 Impacts and Mitigation Measures 4-12 5.0 Water Resource 5-1 5.1 Occupancy Rate 5-1 5.2 Potable Water Demand 5-1 5.3 Water Source 5-3 5.3.1 Preferred Option 5-3 5.4 Water Supply Description 5-5 5.5 Ground and Surface Waters Analysis 5-5 5.5.1 Water Quality -

The Evolutionary Tree of Birds

HANDBOOK OF BIRD BIOLOGY THE CORNELL LAB OF ORNITHOLOGY HANDBOOK OF BIRD BIOLOGY THIRD EDITION EDITED BY Irby J. Lovette John W. Fitzpatrick Editorial Team Rebecca M. Brunner, Developmental Editor Alexandra Class Freeman, Art Program Editor Myrah A. Bridwell, Permissions Editor Mya E. Thompson, Online Content Director iv This third edition first published 2016 © 2016, 2004, 1972 by Cornell University Edition history: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology (1e, 1972); Princeton University Press (2e, 2004) Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030‐5774, USA For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell. The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

YUCATAN, MEXICO - 2018 Th Th 27 Jan – 4 Feb 2018 HIGHLIGHTS Either for Rarity Value, Excellent Views Or Simply a Group Favorite

YUCATAN, MEXICO - 2018 th th 27 Jan – 4 Feb 2018 HIGHLIGHTS Either for rarity value, excellent views or simply a group favorite. Yucatan Wren Ocellated Turkey Bare-throated Tiger Heron Lesser Roadrunner Yucatan Bobwhite American Flamingo Mexican Sheartail Gray-throated Chat Buff-bellied Hummingbird Rose-throated Tanager Black Catbird Black-headed Trogon White-bellied Emerald White-bellied Wren Lesson’s Motmot Eye-ringed Flatbill Blue Bunting Pale-billed Woodpecker Keel-billed Toucan Bat Falcon White-necked Puffbird Laughing Falcon Collared Aracari Tawny-winged Woodcreeper Cozumel Emerald Cozumel Vireo Yellow-tailed Oriole Ruddy Crake Yucatan Woodpecker Turquoise-browed Motmot Yucatan Jay Couch’s Kingbird Rufous-tailed Jacamar King Vulture Green Jay Velasquez’s Woodpecker Leaders: Rose-throated Steve Bird, Becard Gina Nichol Black Skimmers Yellow-throated Warbler Bright-rumped Attila “Golden” Warbler Magnificent Frigatebirds Vermilion Flycatcher Yucatan Vireo Red-legged Honeycreepers Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl Morelet’s Crocodile Yucatan Black Howler SUMMARY: Our winter getaway to the Yucatan in Mexico enjoyed some lovely warm, not too hot weather and some fabulous birds. The dinners and picnic lunches were excellent and our two superb drivers helped things run smoothly. Our local guide knew many of the key birding spots and we soon racked up a great list of sought after species. One of the real highlights was going out on a boat trip from Rio Lagartos where we enjoyed superb views of many water birds, including American Flamingos, Reddish Egrets darting around, terns, pelicans, a Morelet’s Crocodile and even Common Black Hawks sat around looking for a hand out. The dry thorny scrub produced many more species and a special treat was visiting Muyil Ruins where we not only enjoyed some excellent archaeology but also some great wildlife which including 6 Ocellated Turkeys, many other nice birds and an amazing experience with the loudest Yucatan Black Howler monkey in existence.