The Impacts of Targeted Public and Nonprofit Investment on Neighborhood Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valentine Richmond History Walks Self-Guided Walk of the Oregon Hill Neighborhood

Valentine Richmond History Walks Self-Guided Walk of the Oregon Hill Neighborhood All directions are in italics. Enjoying your tour? The tour starts in front of St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, 240 S. Laurel Street Take a selfie (near the corner of Idlewood Avenue and Laurel Street). and tag us! @theValentineRVA WELCOME TO OREGON HILL The Oregon Hill Historic District extends from Cary Street to the James River and from Belvidere Street to Hollywood Cemetery and Linden Street. Oregon Hill’s name is said to have originated in the late 1850s, when a joke emerged that people who were moving into the area were so far from the center of Richmond that they might as well be moving to Oregon. By the mid-1900s, Oregon Hill was an insular neighborhood of white, blue-collar families and had a reputation as a rough area where outsiders and African-Americans, in particular, weren’t welcome. Today, Oregon Hill is home to two renowned restaurants and a racially and economically diverse population that includes long-time residents, Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) students and people wanting to live in a historic part of Richmond. You’re standing in front of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, which began in 1873 as a Sunday school mission of St. Paul's Episcopal Church in downtown Richmond. The original church building, erected in 1875, was made of wood, but in 1901, it was replaced by this building. It is Gothic Revival in style, and the corner tower is 115 feet high. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. -

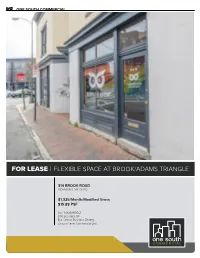

For Lease | Flexible Space at Brook/Adams Triangle

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR LEASE | FLEXIBLE SPACE AT BROOK/ADAMS TRIANGLE 314 BROOK ROAD RICHMOND, VA 23220 $1,325/Month/Modified Gross $19.88 PSF PID: N0000119012 800 Leasable SF B-4 Central Business Zoning Ground Level Commercial Unit PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO Downtown Arts District Storefront A perfect opportunity located right in the heart of the Brook/Adams Road triangle! This beautiful street level retail storefront boasts high ceilings, hardwood floors, exposed brick walls, and an expansive street-facing glass line. With flexible use options, this space could be a photographer studio, a small retail maker space, or the office of a local tech consulting firm. An unquestionable player in the rise of Broad Street’s revitalization efforts underway, this walkable neighborhood synergy includes such residents as Max’s on Broad, Saison, Cite Design, Rosewood Clothing Co., Little Nomad, Nama, and Gallery5. Come be a part of the creative community that is transforming Richmond’s Arts District and meet the RVA market at street level. Highlights Include: • Hardwood Floors • Exposed Brick • Restroom • Janitorial Closet • Basement Storage • Alternate Exterior Entrance ADDRESS | 314 Brook Rd PID | N0000119012 STREET LEVEL BASEMENT STOREFRONT STORAGE ZONING | B-4 Central Business LEASABLE AREA | 800 SF LOCATION | Street Level STORAGE | Basement PRICE | $1,325/Mo/Modified Gross 800 SF HISTORIC LEASABLE SPACE 1912 CONSTRUCTION PRICE | $19.88 PSF *Information provided deemed reliable but not guaranteed 314 BROOK RD | RICHMOND VA 314 BROOK RD | RICHMOND VA DOWNTOWN ARTS DISTRICT AREA FAN DISTRICT JACKSON WARD MONROE PARK 314 BROOK RD VCU MONROE CAMPUS RICHMOND CONVENTION CTR THE JEFFERSON BROAD STREET MONROE WARD RANDOLPH MAIN STREET VCU MED CENTER CARY STREET OREGON HILL CAPITOL SQUARE HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY DOWNTOWN RICHMOND CHURCH HILL ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM ANN SCHWEITZER RILEY [email protected] 804.723.0446 1821 E MAIN STREET | RICHMOND VA ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL 2314 West Main Street | Richmond VA 23220 | onesouthcommercial.com | 804.353.0009 . -

Downtown Richmond, Virginia

Hebrew Cemetery HOSPITAL ST. Shockoe Cemetery Downtown Richmond, Virginia Visitor Center Walking Tour Richmond Liberty Trail Interpretive Walk Parking Segway Tour Richmond Slave Trail Multiuse Trail Sixth Mt. Zion Baptist Church Park Water Attraction James River Flood Wall National Donor J. Sargeant Reynolds Memorial Community College Maggie Walker Downtown Campus National Bill “Bojangles” Oliver Hill Greater Robinson Statue Historic Site Bust Richmond Richmond Convention Coliseum Abner Center Clay Park Hippodrome Theater Museum and Valentine White House of John Richmond the Confederacy Jefferson RICHMOND REGION Abady Marshall History Center Park VISITOR CENTER House Festival VCU Medical Center Patrick Park and MCV Campus Richmond’s Henry Park City First African African Burial Stuart C. Virginia Repertory The National Hall Old City Monumental Siegel Center Sara Belle and Theater Hall Church Baptist Church Ground Neil November St. John’s Theatre Libraryof Virginia Church Richmond Virginia Civil Rights Lumpkin’s Jail Elegba Center Stage George Monument Washington River Chimborazo Folklore . Winfree Cottage T Monument S Medical Museum Society City Segs H Executive T 2 Bell Virginia Mansion 1 Tower Beth Ahabah Capitol Old Museum & St. Paul’s 17th Street Episcopal First Fellows Edgar Allan Archives Freedom Reconciliation Hall Farmers’ Market Soldiers & Sailers VCU Monroe Richmond Bolling Church Statue Poe Museum Monument Park Campus Monroe Center Public Library Haxall Main Street Cathedral of the Park House Auction Station Virginia W.E. Singleton -

406 W Broad St Richmond, Va 23220

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR LEASE | 4,000 SF W BROAD ST COMMERCIAL SPACE 406 W BROAD ST RICHMOND, VA 23220 $3,500/Month/Modified Gross PID: N0000206019 4,000+/- SF TOTAL 1,636+/- SF Street Level Retail 2,364+/- SF Lower Level Office/Storage 2 Off-Street Parking Spaces B-4 Central Business Zoning PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO Downtown Commercial Space on W Broad St This 4,000+/- SF commercial space is available for immediate lease. Located on this busy stretch of W Broad St in Richmond’s Downtown Arts District, this listing features 1,636+/- SF of street level space. Large storefront windows, exposed brick, and hardwood flooring are highlights of the interior that was completely renovated in 2010. In addition, 2,364+/- SF is available on the lower level for offices or storage. The B-4 Central Business zoning allows for a wide variety of commercial uses including retail, restaurant, office, personal service, and many others, and makes this location ideal for a new Downtown business. ADDRESS | 406 W Broad St STREET LEVEL 1,636+/- SF COMMERCIAL FIRST LEVEL PID | N0000206019 ZONING | B-4 Central Business LEASABLE AREA | 4,000 +/- SF STREET LEVEL | 1,636 +/- SF PRICE | $3,500/Mo/Modified Gross 2,364+/- SF B-4 CENTRAL PARKING | 2 Spaces Off-Street LOWER LEVEL BUSINESS ZONING *Information provided deemed reliable but not guaranteed 406 W BROAD ST | RICHMOND VA 406 W BROAD ST | RICHMOND VA DOWNTOWN ARTS DISTRICT N BELVIDERE ST JACKSON WARD FAN DISTRICT 406 W BROAD ST MONROE PARK N ADAMS ST VCU MONROE CAMPUS RICHMOND CONVENTION CTR THE JEFFERSON BROAD STREET MONROE WARD RANDOLPH MAIN STREET VCU MED CENTER CARY STREET OREGON HILL CAPITOL SQUARE HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY UNION HILL DOWNTOWN RICHMOND CHURCH HILL ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL CONTACT CLINT GREENE [email protected] 804.873.9501 1821 E MAIN STREET | RICHMOND VA ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL 2314 West Main Street | Richmond VA 23220 | onesouthcommercial.com | 804.353.0009 . -

Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2016 Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia Sharron Smith College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Sharron, "Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1477068460. http://doi.org/10.21220/S2D30T This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia Sharron Renee Smith Richmond, Virginia Master of Liberal Arts, University of Richmond, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, Mary Baldwin College, 1989 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2016 © Copyright by Sharron R. Smith ABSTRACT The Virginia State Constitution of 1869 mandated that public school education be open to both black and white students on a segregated basis. In the city of Richmond, Virginia the public school system indeed offered separate school houses for blacks and whites, but public schools for blacks were conducted in small, overcrowded, poorly equipped and unclean facilities. At the beginning of the twentieth century, public schools for black students in the city of Richmond did not change and would not for many decades. -

The Historic Residential Suburb of Highland Springs Henrico County, Virginia

Evaluation of Eligibility For Inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places: The Historic Residential Suburb of Highland Springs Henrico County, Virginia Paula Barlowe Prepared for: Henrico County Department of Community Revitalization URSP 797, Directed Research, VCU Professor Kimberly Chen January 5, 2014 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................Page 1 The Neighborhood of Highland Springs............................................................Page 3 History...............................................................................................................Page 3 Restrictive Covenants to Deed of Sale .............................................................Page 5 Plats..................................................................................................................Page 5 Life in Highland Springs....................................................................................Page 6 1890-1920....................................................................................................Page 6 The 1920’s to 1940s ....................................................................................Page 7 Mid-20th c. to Present..................................................................................Page 7 African Americans in Highland Springs........................................................Page 9 Recent Statistics: Population, Demographics, & Housing ...............................Page -

Learning Together in Highland Park to Build Civic Capacity

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 Learning Together in Highland Park to Build Civic Capacity Grace Leonard Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5371 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Learning Together in Highland Park to Build Civic Capacity A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Urban and Regional Planning at Virginia Commonwealth University by Grace Leonard, Master of Urban and Regional Planning Director: Dr. Meghan Gough, Associate Professor & Program Chair L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs Virginia Commonwealth University Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia May 2018 Acknowledgements As I finish this paper I am months away from the ten-year anniversary of my move to Richmond, and this work builds on a decade of learning in, and engaging with, a place. Richmond is the city that I will forever see as the community where I found my own footing. As I learned to find language for the city’s assets, and needs, I began to find language for my assets and needs. Thanks to the VCU Master of Urban and Regional Planning program for providing a curriculum that gives attention to both the processes and outcomes my project describes. -

Richmond Region Attractions Map RICHMOND RACEWAY COMPLEX Visitor Center Walking Tour Richmond Liberty Trail Interpretive Walk

EXIT Lewis Ginter 81 Botanical Garden Richmond International Raceway Richmond Region Attractions Map RICHMOND RACEWAY COMPLEX Visitor Center Walking Tour Richmond Liberty Trail Interpretive Walk Bryan Park Classic Parking Segway Tour Richmond Slave Trail Amphitheater Multiuse Trail Park Water Attraction James River Flood Wall Arthur Ashe, Jr. Athletic Center SPARC (School of the Performing Arts in the The Diamond The Shops at Richmond Community) Greyhound Virginia Union University Willow Lawn Henley Street Bus Terminal Jackson Hebrew Theatre Co Cemetery Willow Lawn Sports Backers Ward Theatre Children’s Stadium Matthew Fontaine Museum of Sixth Mt. Zion Shockoe Hill Virginia Repertory Maury Monument Stonewall Richmond Baptist Church Cemetery Theatre: Children’s Jackson Science Museum Theatre of Virginia Abner Arthur Ashe, Jr. Monument of Virginia HistoricClay Park Monument Bill “Bojangles” The Showplace Museum Jefferson Robinson Statue Davis Broad Monument Robert E. Lee Stuart C. District Siegel Center Virginia Monument J.E.B. Stuart Street Historical National Monument Maggie Walker Greater Society National Donor Virginia Museum Virginia Repertory Richmond Memorial of Fine Arts Beth Ahabah Theatre: Sara Belle and Historic Site Convention Virginia Center Museum & Archives Neil November Theatre Center for Architecture Hippodrome Theater J. Sargeant Reynolds Confederate War Cathedral of the Sacred Heart & Oliver Richmond Community College Memorial Chapel VCU Monroe Museum of VA Catholic History Coliseum Park Campus Hill Bust Downtown Campus Monroe RICHMOND REGION Wilton House Park VISITOR CENTER W.E. Singleton Elegba Fan Center for the Folklore Performing Arts Altria Society Theater John Marshall Valentine Abady Courthouse John Marshall Richmond Festival Park House History Center Carytown Richmond Museum and Agecroft Hall Public The National City Hall Theater White House of Library the Confedracy Monroe Richmond Library of Paddle Boat CenterStage Rental Confederate Bolling Haxall Virginia Monument House Ward Old City VCU Medical Center Christopher St. -

Golden Hammer Awards

Golden Hammer Awards 1 WELCOME TO THE 2018 GOLDEN HAMMER AWARDS! Storefront for Community Design and Historic You are focusing on blight and strategically selecting Richmond welcome you to the 2018 Golden Hammer projects to revitalize at risk neighborhoods. You are Awards Ceremony! As fellow Richmond-area addressing the challenges to affordability in new and nonprofits with interests in historic preservation and creative ways. neighborhood revitalization, we are delighted to You are designing to the highest standards of energy co-present these awards to recognize professionals efficiency in search of long term sustainability. You are working in neighborhood revitalization, blight uncovering Richmond’s urban potential. reduction, and historic preservation in the Richmond region. Richmond’s Golden Hammer Awards were started 2000 by the Alliance to Conserve Old Richmond Tonight we celebrate YOU! Neighborhoods. Historic Richmond and Storefront You know that Richmond has much to offer – from for Community Design jointly assumed the Golden the tree-lined streets of its historic residential Hammers in December 2016. neighborhoods to the industrial and commercial We are grateful to you for your commitment to districts whose collections of warehouses are attracting Richmond, its quality of life, its people, and its places. a diverse, creative and technologically-fluent workforce. We are grateful to our sponsors who are playing You see the value in these neighborhoods, buildings, important roles in supporting our organizations and and places. our mission work. Your work is serving as a model for Richmond’s future Thank you for joining us tonight and in our effort to through the rehabilitation of old and the addition of shape a bright future for Richmond! new. -

NPS Form 10 900 OMB No. 1024 0018

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property Historic name Three Chopt Road Historic District Other nameslsite VA DHR No. 127-6064 number 2. Location Street & Both sides of a 1.3 mile stretch of Three Chopt Rd from its not for number intersection with Cary St Rd on the south to Bandy Rd on the north. City or Richmond town State zip - Virginia code VA county .- In9endentCity code 760 code --23226 3. StatelFederal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this xnomination -request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and / meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property xmeets -does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: - natiob - statewide -x local Signature of certifyiirg officialmitle Virginia Department of Historic Resources State or Federal agencylbureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property - meets -does not meet the National Register criteria. -

General Photograph Collection Index-Richmond Related Updated 10/3/14

THE VALENTINE General Photograph Collection Richmond-related Subjects The Valentine’s Archives hold one million photographs that document people, places, and events in Richmond and Virginia. This document is an index of the major Richmond- related subject headings of the Valentine’s General Photograph Collection. Photographs in this collection date from the late 19th century until the present and are arranged by subject. Additional major subjects in the General Photograph Collection include: • Civil War • Cook Portrait Collection – Portraits of famous Virginians • Museum Collection – Museum objects and buildings • Virginia Buildings and Places The Valentine also has the following additional photograph collections: • Small Photograph Collection – Prints 3”x5” and under • Oversized Photograph Collection – Large and panoramic prints • Cased Image Collection – 400+ daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, tintypes, and framed photographs • Stereograph Collection – 150+ views of Richmond, Virginia and the Civil War • Over 40 individual photograph collections – Including those of Robert A. Lancaster, Jr., Palmer Gray, Mary Wingfield Scott, Edith Shelton, and the Colonial Dementi Studio. Please inquire by email ([email protected]), fax (804-643-3510), or mail (The Valentine, Attn: Archives, 1015 E. Clay Street, Richmond, VA 23219) to schedule a research appointment, order a photograph, or to obtain more information about photographs in the Valentine’s collection. Church Picnic in Bon Air, 1880s Cook Collection, The Valentine Page 1 of 22 The Valentine -

Virginia ' Shistoricrichmondregi On

VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUPplanner TOUR 1_cover_17gtm.indd 1 10/3/16 9:59 AM Virginia’s Beer Authority and more... CapitalAleHouse.com RichMag_TourGuide_2016.indd 1 10/20/16 9:05 AM VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUP TOURplanner p The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collection consists of more than 35,000 works of art. © Richmond Region 2017 Group Tour Planner. This pub- How to use this planner: lication may not be reproduced Table of Contents in whole or part in any form or This guide offers both inspira- by any means without written tion and information to help permission from the publisher. you plan your Group Tour to Publisher is not responsible for Welcome . 2 errors or omissions. The list- the Richmond region. After ings and advertisements in this Getting Here . 3 learning the basics in our publication do not imply any opening sections, gather ideas endorsement by the publisher or Richmond Region Tourism. Tour Planning . 3 from our listings of events, Printed in Richmond, Va., by sample itineraries, attractions Cadmus Communications, a and more. And before you Cenveo company. Published Out-of-the-Ordinary . 4 for Richmond Region Tourism visit, let us know! by Target Communications Inc. Calendar of Events . 8 Icons you may see ... Art Director - Sarah Lockwood Editor Sample Itineraries. 12 - Nicole Cohen G = Group Pricing Available Cover Photo - Jesse Peters Special Thanks = Student Friendly, Student Programs - Segway of Attractions & Entertainment . 20 Richmond ; = Handicapped Accessible To request information about Attractions Map . 38 I = Interactive Programs advertising, or for any ques- tions or comments, please M = Motorcoach Parking contact Richard Malkman, Shopping .