CHATHAM HISTORICAL SOCIETY Medway Chronicle 'Keeping Medway's History Alive'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garage Sites in Medway (Waiting List)

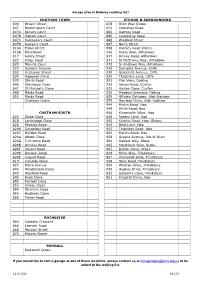

Garage sites in Medway (waiting list) CHATHAM TOWN STROOD & SURROUNDING 804 Bryant Street 878 Bligh Way Shops 807 Blockmakers Court 879 Carnation Road 807A Joiners Court 882 Darnley Road 807B Oakum Court 885 Leybourne Road 807C Sailmakers Court 888 Windmill Street 807D Sawyers Court 897 North Street 816A Eldon Street 898 Darnley Road Stores 816B Hardstown 916 Avery Way, Allhallows 817 Henry Street 917 Binney Road, Allhallows 823 Kings Road 971 St Matthews Way, Allhallows 829 Melville Court 972 St Andrews Way, Allhallows 830 Symons Avenue 918 Swingate Avenue, Cliffe 832 Ordnance Street 919 Quickrells Avenue, Cliffe 834 Hopewell Drive 920 Thatchers Lane, Cliffe 839 Sturla Road 921 Pips View, Cooling 846 Glenwood Close 922 James Road, Cuxton 847 St Michael’s Close 923 Hayley Close, Cuxton 848 Maida Road 935 Meadow Crescent, Halling 850 Maida Road 939 Hillview Cottages, High Halstow Chatham Grove 979 Harrison Drive, High Halstow 944 Miskin Road, Hoo 945 Wylie Road, Hoo CHATHAM SOUTH 946 Kingsnorth Villas, Hoo 820 Slade Close 948 Ropers Lane, Hoo 818 Lordswood Close 950 Knights Road, Hoo (Shops) 826 Phoenix Road 943 Bells Lane, Hoo 826H Sandpiper Road 955 Trubridge Road, Hoo 826C Bulldog Road 956 Marley Road, Hoo 826A Albion Close 958 Grayne Avenue, Isle of Grain 826G Turnstone Road 981 Mallard Way, Stoke 826B Achilles Road 965 Marshland View, Stoke 826F Valiant Road 967 Button Drive, Stoke 826D Renown Road 926 Miller Way, Frindsbury 826E Cygnet Road 927 Wainscott Walk, Frindsbury 819 Ironside Close 928 Holly Road, Frindsbury 827 Malta Avenue 929 Winston Drive, Frindsbury 842 Walderslade Road 930 Hughes Drive, Frindsbury 843 Wayfield Road 933 Gardenia Close, Frindsbury 849 Ryde Close 951 Kingshill Drive, Hoo 852 Penfold Close 853 Vulcan Close 854 Shanklin Close 855 Anglesey Close 856 Fisher Road ROCHESTER 860 Cordelia Crescent 866 Leander Road 868 Mordon Street 870 Princes Street TWYDALL Eastcourt Green If you would like to rent a garage at one of these locations, please contact us at [email protected] to be added to the waiting list. -

Clarion We Reported on the Renewed Interest in an Airport in the Thames Estu- Ary to Replace Heathrow As a Major Hub Airport

Our Community— Autumn Forward Together Edition 2012 Building on Jubilee Success Despite the rainy weather the Jubilee events in both Cliffe and Cliffe Woods were still a great success. In Cliffe Woods this was the first community event in many years and has inspired the Community Association to organise other events throughout the year and an Annual Summer Fair. (see page 2 for details). In Cliffe the early Jubilee event meant there was no Cliffe Fayre this year, but an extra event is planned for Saturday 27th October at the Buttway and Church—see inside for more details. The success of these events are also down to the support of local vil- L lagers like yourselves. It is this that makes it worthwhile—can you help with future events? Estuary Airport Update In the last edition of the Clarion we reported on the renewed interest in an airport in the Thames Estu- ary to replace Heathrow as a major hub airport. There has been publicity for an island in the Thames (Boris Island) and also at Grain (Foster’s Folly), but less for a proposal that sites the airport between Cliffe and High Halstow. We were promised consultation (again) in the spring, but this was delayed until after the London Mayor- al Elections in May. They were then planned for the summer but postponed to avoid the Olympics, Alt- hough many people expected they would finally get underway in the Autumn there has been a further delay so that the conclusions are not published until after the 2015 General (and Local) Elections., so we Clarion will be watching out for ‘calls for evidence’ and ‘scoping’ reports which often start the process. -

SEND Parent Leaflet 2019-20

Frequently Used SEN Terms Who will support my child? Within school All teaching staff fulfil the role and responsibility for the progress of all their pupils. Our SENCO is Miss Heard. High Halstow Our partnerships Primary At High Halstow Primary Academy, Academy we work closely with other professionals: Marlborough Outreach Team SEND Parent/Carer Leaflet Contact Us: Bradfields Outreach 2019-20 Medway Inclusion Team High Halstow Primary Academy Speech & Language Therapist Please see our Local Offer Occupational Therapist Harrison Drive document and the LAT SEN Educational Psychologist High Halstow, Rochester, Kent, Policy for further detail. ME3 8TF Dog Training Art and Play Therapist Telephone: 01634 251098 Miss R Heard Your child may work with other Email: office@highhalstowprima professionals in addition to the Contact: [email protected] school staff to support their ryacademy.org.uk learning. How are children with Special Educational Needs identified and assessed? What We Offer At High Halstow, all our children’s needs are identified and met as early as possible through: observation, assessment, target setting and monitoring arrangements. listening to and following up parental concerns and the child’s views, wishes and feelings. the analysis of data including baseline What are the different types of assessments and end of Key Stage achievement to support available for children with We aim to give every pupil the opportunity track individual children’s progress over time. SEND in the school? to develop his/her full potential. It reviewing and improving teachers’ understanding recognises that all pupils have their own of a wide range of needs and effective strategies to Class teacher input, through targeted particular needs and seeks to ensure that meet those needs. -

New Properties Will Be Added Daily. Please Check Individual Adverts for Closing Dates

New properties will be added daily. Please check individual adverts for closing dates Studio sheltered flat ref no: 100 Location:Rhodes House, Beacon Hill, Unfurnished studio flat on the first floor. Living room and Chatham bedroom are combined. Communal activities include Landlord:mhs homes coffee mornings. Applicants must be 60 and over. £250 Social Rent:£115.93 pw Argos voucher will be given to help with furnishings. Service Charge:£14.72 pw Offers subject to satisfying the criteria of a Needs & Risk (£14.72 pw of which is not eligible for Assessment. First weeks rent to be paid in advance. benefit) Bidding closes:04 Oct 2021 Studio sheltered flat ref no: 870 Location:Brennan House, Victoria Shared garden, gas central heating, shower, energy Street, Gillingham performance Available at viewing. Landlord:Medway Council First floor studio flat. lift in building but must be able to Social Rent:£61.59 pw manage stairs in an emergency. 24/7 lifeline. Laundry. no Service Charge:£45.86 pw pets allowed. 2 weeks rent in advance. Bidding closes:03 Oct 2021 1 bed sheltered flat ref no: 591 Location:Spinnaker Court, The First floor 1 bedroom flat. Available November. Shared Fairway, Rochester, Kent garden, electric heating, bath and shower, energy Landlord:Moat Homes Ltd performance available at viewing. No list. No pets Social Rent:£85.00 pw allowed. Property is Unfurnished. No lift available. Service Charge:£20.00 pw Property is sheltered, 55s and over only. Close to Bidding closes:30 Sep 2021 transport and amenities. Please be advised an upfront fee of a weeks rent and occupation charge (if applicable) will be required. -

Time and Tides - the Project

Evaluation Report Contents 1. Introduction 2. Aims and achievements 3. Quantitative Monitoring Summary 4. Qualitative Feedback 5. Project Profile and Publicity 6. Lessons Learned 7. Future opportunities 1. Time and Tides - The project The Time and Tides project was a local history and community arts project funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and Medway Council. It was designed to explore the local history, traditions and cultural customs of rural Medway with particular focus on the villages of Cuxton, High Halstow and Upnor, while providing local history learning and arts opportunities for people in the process. The project ran for one year from November 2011 until November 2012. The project was extremely popular, with over 1700 people engaging in the project in some way, including primary school children, teenagers, people of working age and older people. Levels of engagement ranged from people with a strong and existing interest in local history to those who had never taken part in heritage events before. Some people became core volunteers to the project, others enjoyed attending events and made a conscious effort to attend while others engaged on a more casual basis, dropping into occasional sessions or coming across an event or exhibition simply by chance. The Medway Area Medway is divided into the heavily populated towns of Rainham, Gillingham, Chatham, Rochester and Strood and the rural areas to the North and South of these towns. The three villages of High Halstow, Cuxton and Upnor are situated on the Medway Peninsula, a particularly rurally isolated area with little agriculture or industry covering two thirds of the Medway geographical area. -

1 Introduction 1.1 What This Chapter Covers

Children and Young People: introduction | 1 1 Introduction 1.1 What this chapter covers This chapter presents data on issues affecting the health and wellbeing of children and young people in the London Borough of Hackney and the City of London. The analysis identifies areas of unmet need through examination of health inequalities and by comparing local data with other areas and over time. The chapter also outlines the evidence for what works in meeting children and young people’s health needs, and describes key services and support available locally with regards to prevention, identification and care/treatment. Much of the information contained within this chapter has been drawn from two health needs assessments conducted over the period 2015-2016 – one for 0-5 year olds, and the other for 5-19 year olds. These needs assessments can be found on the Hackney Council website. 1 The main local services for children and young people are listed within this chapter to highlight the range of support that is available. However, this is not intended to be a comprehensive directory of all local services. To search for further services in Hackney, please consult the ‘Children & Young People’s Resource Guide’, which has recently been updated (July 2016) by Hackney Children’s and Young People’s Services (CYPS).2 Please note, given the small number of children and young people resident in the City of London, many services are shared with neighbouring boroughs. However, they are not always shared with Hackney (for instance, youth offending is shared with Tower Hamlets). Where possible, services covering the City of London have been described. -

765 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

765 bus time schedule & line map 765 High Halstow - Hoo - Strood - London View In Website Mode The 765 bus line (High Halstow - Hoo - Strood - London) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) High Halstow: 4:55 PM (2) Westminster: 6:35 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 765 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 765 bus arriving. Direction: High Halstow 765 bus Time Schedule 23 stops High Halstow Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:55 PM Blackfriars Puddle Dock, London Tuesday 4:55 PM Cannon Street Wednesday 4:55 PM Upper Thames Street, London Thursday 4:55 PM The Tower Of London (Tb) Friday 4:55 PM Tower Hill, London Saturday Not Operational Canada Square North (H) 8 Canada Square, London Bexley Black Prince, Bexley Rochester Way (W), London 765 bus Info Direction: High Halstow Tollgate, Gravesend Stops: 23 Cyclopark, England Trip Duration: 115 min Line Summary: Blackfriars, Cannon Street, The Old Watling Street, Strood Tower Of London (Tb), Canada Square North (H), Bexley Black Prince, Bexley, Tollgate, Gravesend, Old Stangate Road, Earl Estate Watling Street, Strood, Stangate Road, Earl Estate, Parkƒelds, England Bligh Way Shops, Earl Estate, Fulmar Road, Earl Estate, Maple Road Bottom, Earl Estate, Darnley Bligh Way Shops, Earl Estate Arch, Strood, Post O∆ce, Strood, English Martyrs Church, Frindsbury Extra, Bingham Road, Frindsbury Fulmar Road, Earl Estate Extra, The Sans Pareil, Wainscott, Chattenden Lane, Chattenden, Swimming Pool, Hoo St Werburgh, St Maple Road Bottom, Earl Estate Werburgh Crescent, Hoo St Werburgh, The Five Bells, Hoo St Werburgh, Bell's Lane, Hoo St Werburgh, Darnley Arch, Strood Fourwents Road, Hoo St Werburgh, Longƒeld Avenue, High Halstow Post O∆ce, Strood 13 - 17 North Street, England English Martyrs Church, Frindsbury Extra Bingham Road, Frindsbury Extra 185 Frindsbury Road, England The Sans Pareil, Wainscott Wainscott Road, Frindsbury Extra Civil Parish Chattenden Lane, Chattenden Old School Court, Hoo St. -

Appendix B Introduction 1. This Appendix Sets out How The

Appendix B Introduction 1. This appendix sets out how the proposed warding scheme addresses the second and third of the Boundary Commission’s three statutory criteria for local government electoral reviews: the need to secure equality of representation; the need to reflect the identities and interests of local communities; and the need to secure effective and convenient local government. 2. Hackney’s diverse mix of people from different backgrounds gives it the third greatest degree of ethnic diversity, and the fifth greatest degree of religious diversity amongst local authorities in England and Wales. Ethnic and religious groups are widely dispersed across the borough. The one exception to this is the Orthodox Jewish/Charedi community in the Stamford Hill area, which is noticeably more concentrated than other groups. 3. Nearly three in five Hackney residents say they feel they belong either fairly or very strongly to their local neighbourhood (57%). This compares well to the London average of 52%. Many people feel they ‘belong’ in many different ways – to a small local area or estate, to one of Hackney’s distinctive sub-localities (source: Hackney Cohesion Review, published July 2010). 4. Our approach has been to seek to strengthen this identification with local areas through their reflection in the proposed warding arrangements, including retaining existing wards where possible, while correcting some known anomalies, for example where a small part of a housing estate falls in a different ward to the majority of the estate. 5. The fundamental problem that we have had to address is the imbalance between the south west of the borough and the north. -

July 2010 Learn Something New with Medway Adult Education

High Halstow TIMES Home of the Heron July 2010 Learn something new with Medway Adult Education Do you want to put your grey matter to the test and learn something new? The latest Medway Adult Community Learning Service (MACLS) directory is available now and is crammed full of exciting and fun courses, from learning a new language to brushing up on your maths and English skills, to discovering how to make your own clothes and basic DIY skills. There are a wide range of courses available for everyone of all ages who want to learn a new skill to improve their employability during the recession, with computing courses, website design, book keeping and the national Train to Gain qualifications. More than 7,000 people studied with MACLS in 2009/10; the youngest was a six-month old baby on a baby massage course, the oldest was 84-year-old. Families are also encouraged to spend quality time together, while learning valuable skills such as cookery, craft and sports and leisure. Gillingham FC is providing football coaching sessions for dads and their children, while families can learn about nature on a mini beast safari at Capstone Farm Country Park. MACLS teamed up with the Hundred of Hoo School in the spring to extend the range of courses on offer to people living on the Peninsula and surrounding areas who may not be able to attend courses at our other centres. The initial response was overwhelming and the range of courses has been increased. Portfolio Holder for Community Services Cllr Howard Doe said: “This directory offers a wide range of courses, whether you want to learn a new skill and improve your career prospects during the recession, or just want to learn for fun. -

Situation of Polling Stations

Medway Council Election of Police & Crime Commissioner For the Area of Kent To be held on Thursday, 6th May 2021 The situation of the Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote at each station are set out below: Polling Station and Address Persons entitled to vote at that station 1 / CCC1 Balfour Junior School, Balfour Road, Chatham, ME4 6QX 1 to 3683 2 / CCC2 New Road School, Bryant Street, Chatham, ME4 5QN 1 to 2071 3 / CCC3 White Road Community Centre, Keyes Avenue, Chatham, ME4 5UN 1 to 4345 4 / CCC4 All Saints Church Hall, Magpie Hall Road, Chatham, ME4 5NE 1 to 1376 5 / CLC1 Lordswood School, Lordswood Lane, Chatham, ME5 8NN 1 to 3352 6 / CLC2 St Davids Church Hall, Off Newton Close, Lordswood, Chatham, ME5 8TR 1 to 3274 7 / CLC3 Grand Quee Suite, Lordswood Leisure Centre, North Dane Way, ME5 8YE 1 to 298 8 / CLW1 Luton Library, 2 Nelson Terrace,, Chatham, ME5 7LA 1 to 3024 9 / CLW2 All Saints Church Hall, Magpie Hall Road, Chatham, ME4 5NE 1 to 2557 10 / CLW3 Stonecross Lea Community Centre, Stonecross Lea, Chatham, ME5 0BL 1 to 1550 11 / CLW4 Wayfield Primary School, Wayfield Road, Chatham, ME5 0HH 1 to 3146 12 / CPP1 Church of Christ the King, Dove Close, Princes Park, Chatham, ME5 7PX 1 to 3034 13 / CPP2 Maundene School, Swallow Rise, Chatham, ME5 7QB 1 to 4394 14 / CPP3 Church of Christ the King, Dove Close, Princes Park, Chatham, ME5 7PX 1 to 224 15 / CW1 Hook Meadow Community Centre, King George Road, Chatham, ME5 0TZ 1 to 4212 16 / CW2 St Williams Church, Walderslade Village Centre, Walderslade, -

Rural Community Profile for High Halstow (Parish)

1 Rural community profile for High Halstow (Parish) Action with Communities in Rural England (ACRE) Rural evidence project October 2013 Community profile for High Halstow (Parish), © ACRE, OCSI 2013. Finding your way around this profile report 2 A national review carried out by John Egan highlighted a set of characteristics that a community should have in order to create thriving, vibrant, sustainable communities to improve the quality of life of its residents. These characteristics were broken down into a set of themes, around which this report for High Halstow is structured Social and cultural See pages 5-12 for information on who lives in the local community, how the local community is changing and community cohesion… Equity & prosperity See pages13-21 for information on deprivation, low incomes, poor health and disability in the local community… Economy See pages 22-27 for information on the labour market, skills and resident employment… Housing & the built environment See pages 28-33 for information on housing in the local area, household ownership, affordability and housing conditions… Transport and connectivity See pages 34-37 for information on access to transport and services within the local area… Services See pages 38-39 for information on distance to local services… Environmental See pages 40-41 for information on the quality of the local environment… Governance See pages 42-43 for information on the level of engagement within the local community… This report was commissioned by Action with Communities in Rural England (ACRE) and the Rural Community Councils from Oxford Consultants for Social Inclusion (OCSI), www.ocsi.co.uk / 01273 810 270. -

Circular Walks on the Hoo Peninsula

CIRCULARWALKSONTHE Hoo Peninsula Further information Medway Council has a duty to protect, maintain and record rights of way and any problems encountered on them should be reported to: Medway Council, Rights of Way Team, Frontline Services, Regeneration, Community and Culture, Annex B, Civic Centre, Rochester, Kent ME2 4AU Phone: 01634 333333. Minicom: 01634 333111 Email: [email protected] All maps in this publication are reproduced/based upon the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Key to maps Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Medway Council 2008. Copyright licence no: 100024225, 2008 Car parking Text: Medway Swale Estuary Partnership Photography: Mark Loos, David Wise, www.davewise.biz Viewpoint Maps: Sue Meheux, Medway Council Disclaimer Toilet While every care is taken in compiling this publication, neither Medway Council nor its servants or agents can accept any liability whatsoever for any incorrect statement contained herein, nor any omission. Refreshments G2238 Designed by Medway Council’s Communications Team www.medway.gov.uk/communications Point of interest Public house Caution CIRCULARWALKSONTHE Hoo Peninsula Further information Medway Council has a duty to protect, maintain and record rights of way and any problems encountered on them should be reported to: Medway Council, Rights of Way Team, Frontline Services, Regeneration, Community and Culture, Annex B, Civic Centre, Rochester, Kent ME2 4AU Phone: 01634 333333. Minicom: 01634 333111 Email: [email protected] All maps in this publication are reproduced/based upon the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright.