BMH.WS0317.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

W. B. Yeats Easter 1916 This Poem Deals with the Dublin Rebellion Of

W. B. Yeats Easter 1916 This poem deals with the Dublin Rebellion of Easter 1916 which is believed to have been the beginning of modern Ireland, in spite of its immediate failure. Yeats was in Dublin when it happened, and though at first he was against the violence and the bloodshed that accompanied it and he thought the sacrifice of its leaders wasteful, he sympathized with the rebels when sixteen of them were executed. In Stanza One the poet describes the previous lives of the rebels to suggest that they were average or normal citizens who sacrificed their lives for the sake of Irish independence. They were normal Irish people with "vivid faces" and he used to meet them with a nod of the head or saying polite meaningless words. However, he shared with them the love of Ireland: Be certain that they and I But lived where motely is worn The word "motely" means colourful dress which symbolizes Irish people. The stanza ends with "a terrible beauty is born" which may allude to the Birth of Hellen of Troy, Maud Gonne and Ireland because Irish independence will be accompanied by violence and bloodshed. In Stanza Two the poet mentions some of the significant rebels b eginning with "that woman" which refers to Maud Gonne, the most beautiful woman in Ireland according to Ye ats who was with the rebels; she was imprisoned in England after the rising but she escaped to Dublin in 1918. Because of her interest in Irish independence and in politics and argument, her beautiful voice became shrill. -

Easter Rising Heroes 1916

Cead mile Failte to the 3rd in a series of 1916 Commemorations sponsored by the LAOH and INA of Cleveland. Tonight we honor all the Men and Women who had a role in the Easter 1916 Rising whether in the planning or active participation.Irish America has always had a very important role in striving for Irish Freedom. I would like to share a quote from George Washington "May the God in Heaven, in His justice and mercy, grant thee more prosperous fortunes and in His own time, cause the sun of Freedom to shed its benign radiance on the Emerald Isle." 1915-1916 was that time. On the death of O'Donovan Rossa on June 29, 1915 Thomas Clarke instructed John Devoy to make arrangements to bring the Fenian back home. I am proud that Ellen Ryan Jolly the National President of the LAAOH served as an Honorary Pallbearer the only woman at the Funeral held in New York. On August 1 at Glasnevin the famous oration of Padraic Pearse was held at the graveside. We choose this week for this presentation because it was midway between these two historic events as well as being the Anniversary week of Constance Markeivicz death on July 15,1927. She was condemned to death in 1916 but as a woman her sentence was changed to prison for life. And so we remember those executed. We remember them in their own words and the remembrances of others. Sixteen Dead Men by WB Yeats O but we talked at large before The Sixteen men were shot But who can talk of give and take, What should be and what not While those dead men are loitering there To stir the boiling pot? You say that -

Deirdre Toomey

Margaret Ward, Maud Gonne: Ireland's joan of Arc (London: Pandora, I990) X I+ I 2II pp. Margery Brady, The Love Story of Yeats and Maud Gonne (Cork: Mercier Press, I990) I28 pp. Deirdre Toomey Margaret Ward's is the best life of Maud Gonne so far. But that is faint praise. The author has the great advantage of not being at a loss when dealing with Irish politics, and her interest in women in Irish nationalism - see her Unmanageable Revolutionaries: Women and Irish Nationalism (London: Pluto Press, 1984) - results in detailed coverage of Maud Gonne's involvement with women's groups. The biography is very well illustrated and includes a photo graph of the adolescent Iseult which makes the basis of Yeats's infatuation clear. The political and biographical coverage of the earlier part of Maud Gonne's life is not particularly good. Given Margaret Ward's training as a historian, it is regrettable that she presents material from both A Servant of the Queen and Autobiographies without verification. Both are vital but slippery works. Where Yeats's account of his own political career is distorted, self-serving or confused, she follows it without question. I will examine a group of misapprehensions to illustrate the problem. After the debacle of the New Irish Library, Ward states, "Yeats ... did not return to Irish political life tilll897". But Yeats was elected President of the London Young Ireland Society (a front for the Irish National Alliance and Irish Republican Brotherhood) in December 1896: he did not achieve such an important position by staying out of politics. -

Who Were the 'Extremists'?

Who were the ‘Extremists’? Pierce Beasley (Piaras Béaslaí) (1881-1965) was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Irish Volunteers. He worked as a freelance journalist, having been sacked from the Evening Telegraph in 1914 due to his separatist activities. He was also the producer of na h-Aisteoirí, a company of Gaelic amateur actors heavily involved in the IRB. During the Rising, he was deputy commanding officer of the 1 st Dublin Battalion under Edward Daly. He went on to become a Sinn Féin MP in 1918, but left politics following independence. Bealsaí is mentioned in 108 of the 251 reports. Thomas Byrne (1877-1962) was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and a captain in the Irish Volunteers. A veteran of the Second Boer War, where he had fought in the Irish Brigade with Major John MacBride, he led the Maynooth Volunteers to the GPO during the Easter Rising. Following independence, Byrne was appointed Captain of the Guard at Dáil Éireann by Michael Collins. Byrne is mentioned in 108 of the 251 reports, primarily as a frequent visitor to the shop of Thomas J Clarke. Thomas J Clarke (1858-1916), known as Tom, was a central figure in the leadership of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and helped to found the Irish Volunteers in 1913. A key figure in planning the Rising, he was the first to sign the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and was shot in the first round of executions at Kilmainham Jail on 3 May 1916. Clarke lived at 10 Richmond Avenue, Fairview and owned a tobacconist’s shop at 75a Parnell Street which was a hub of IRB activity in the city. -

Assessed Literary Response, Practical Criticism and Situated

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository Reading from nowhere: assessed literary response, Practical Criticism and situated cultural literacy Dr John Gordon, University of East Anglia Abstract School examinations of student responses to literature often present poetry blind or ‘unseen’, inviting decontextualised close reading consistent with the orientation-to- text associated with Practical Criticism (originating in the UK) and New Criticism (originating in the USA). The approach survives in the UK after curricular reforms and government have promulgated cultural literacy as foundational for learning. How is cultural literacy manifest in student responses to literature? To what extent can it be reconciled with Practical Criticism where the place of background knowledge in literary reading is negligible? This article explores their uneasy relationship in pedagogy, curricula and assessment for literary study, discussing classroom interactions in England and Northern Ireland where senior students (aged 16-17) of English Literature consider Yeats’ ‘culture-making’ poem ‘Easter, 1916’. Using methods where teachers withhold contextual information as they elicit students’ responses, the divergent responses of each class appear to arise from differing access to background knowledge according to local though superficially congruent British cultures. The author proposes ‘situated cultural literacy’ to advance the limited application of Practical Criticism in unseen tasks, acknowledge Richards’ original intent, and support the coherence of assessment with curricular arrangements invoking cultural literacy as a unifying principle. Introduction A core academic literacy practice of native-language literary study requires instantaneous close reading of previously unseen texts, presented without contextualising detail. -

W. B. Yeats: a Life and Times

W. B. Yeats: A Life and Times Readers should be alerted to the fact that there are some disparities of dates between the chronologies of Yeats's life in some of the books listed in the Guide to Further Reading. 1858 Irish Republican Brotherhood founded. 1865 13 June, William Butler Yeats born at Georgeville, Sandymount Avenue, in Dublin, son of John Butler Yeats and Susan Yeats (nee Pollexfen). 1867 Family moves to London (23 Fitzroy Road, Regent's Park), so that father can follow a career as a portrait painter. Brothers Robert and Jack and sister Elizabeth born here. The Fenian Rising and execution of the 'Manchester Martyrs'. 1872 Yeats spends an extended holiday with maternal grandparents at Sligo in West of Ireland. 1873 Founding of the Home Rule League. 1874 Family moves to 14 Edith Villas, West Kensington. 1876 Family moves to 8 Woodstock Road, Bedford Park, Chiswick. 1877--80 Yeats attends Godolphin School, Hammersmith, London. Holidays in Sligo. 1877 Charles Stewart Parnell chairman of the Home Rule League. 1879 Irish Land League founded by Parnell and Michael Davitt. 188~1 A decline in J. B. Yeats's income because of the Irish Land War sends the family back to Ireland (Balscadden Cottage, Howth, County Dublin), while he remains in London. 159 160 W. B. Yeats: A Critical Introduction 1881-3 Yeats attends Erasmus Smith High School, Harcourt St, Dublin 1882 Family moves to Island View, Howth. Yeats spends holidays with uncle George Pollexfen, Sligo. Writes first poems. Adolescent passion for his cousin Laura Armstrong. Phoenix Park Murders. Land League suppressed. -

GONNE, MAUD, 1866-1953. Maud Gonne Collection, Circa 1870-1978

GONNE, MAUD, 1866-1953. Maud Gonne collection, circa 1870-1978 Emory University Robert W. Woodruff Library Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Gonne, Maud, 1866-1953. Title: Maud Gonne collection, circa 1870-1978 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 771 Extent: 2.5 linear feet (5 boxes), 1 oversized papers box (OP), and AV Masters: 0.25 linear feet (1 box) Abstract: Collection of letters, photographs and geneological material relating to Maud Gonne including primary materials collected by Professor Conrad Balliet in the course of his research, as well as audiotaped interviews conducted by him with a number of family members and acquaintances. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Special restrictions apply: this collection includes copies of original materials held by other repositories. These copies may not be reproduced without the permission of the owner of the originals. Related Materials in This Repository Maud Gonne and W.B. Yeats papers and W.B. Yeats collection Source Purchase, 1995, with subsequent additions. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Maud Gonne collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Maud Gonne Collection, circa 1870-1978 Manuscript Collection No. 771 Processing Processed, 1995. This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. -

Mccauley Palmer

McCauley Palmer Professor McGowan ENGL 89 28 August 2018 John MacBride Biography Early Life Born on May 7th, 1865, John Macbride was the fifth of five sons to local shopkeepers Patrick and Honoria MacBride in Westport, Co. Mayo (McCracken). MacBride earned the nickname “Foxy Jack” early on due to his distinctive appearance as a ”small, wiry, red-headed man, with grey eyes and a long nose” (McCracken). The foundation of his career began with his education at the Christian Brothers' School in Westport and later at St Malachy's College, located in Belfast. From his fairly extensive education of the time, MacBride then traveled to Castlerea, Co, Roscommon to work in a draper’s shop although he had originally studied medicine. Eventually, his studies led him to pursue chemistry in Dublin working in Moore’s wholesale pharmacy. Early on MacBride became identified by the British as a “dangerous nationalist” due to his association with various Irish nationalist associations including the Irish Republican Brotherhood, Gaelic Athletic Association and Celtic Literary Society. These commitments sparked a life-long commitment to Irish nationalism and led him to travel to the U.S. and South Africa (Wikipedia). Role in Second Anglo-Boer War Perhaps MacBride’s most notable involvement was that of raising the Irish Transvaal Brigade in the Second Anglo-Boer War, later coined as “MacBride’s Brigade”(McCracken). The group arose in October of 1899 with the beginning of the South African War. However, MacBride was originally second in command to an ex-U.S. Cavalry officer, Colonel John Blake, since MacBride lacked true military experience. -

YEATS and WOMEN in the Same Series

YEATS AND WOMEN In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Edited by Warwick Gould Maud Gonne, c. 1900. YEATS AND WOMEN Edited by Deirdre Toomey Yeats Annual No.9 A Special Number Series Editor: Warwick Gould M © Deirdre Toomey 1992 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1992 978-0-333-53647-6 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 33-4 Alfred Place, London WCIE 7DP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 1992 by MACMILLAN ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-11930-1 ISBN 978-1-349-11928-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-11928-8 ISSN 0278-7688 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Contents List of Abbreviations ix Editorial Board Xl Notes on the Contributors Xll List of Plates XVl Editor's Introduction XlX Acknowledgements XXll ARTICLES AND TRANSLATION 3 "Secret Communion": Yeats's Sexual Destiny JOHN HARWOOD 3 At the Feet of the Goddess: Yeats's Love Poetry and the Feminist Occult ELIZABETH BUTLER CULLINGFORD 31 Patronage and Creative Exchange: Yeats, Lady Gregory and the Economy of Indebtedness JAMES PETHICA 60 Labyrinths: Yeats and Maud Gonne DEIRDRE TOOMEY 95 "The Music of Heaven": Dorothea Hunter WARWICK GOULD 132 The Eugenics Movement in the 1930s and the Emergence of On the Boiler DAVID BRADSHAW 189 Florence Farr: Letters toW. -

Have Faith, Watercolor Attributed to Maud Gonne

Have faith, watercolor attributed to Maud Gonne. probably 1910-1944 MS.2020.061 https://hdl.handle.net/2345.2/MS2020-061 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Have faith, watercolor attributed to Maud Gonne. MS.2020.061 - Page 2 - Summary Information Creator: Gonne, Maud, 1866-1953 Title: Have faith, watercolor attributed to Maud Gonne Collection Identifier: MS.2020.061 Date [inclusive]: probably 1910-1944 Physical Description 1.75 Linear Feet (1 container) Language of the English Material: Abstract: Watercolor illustration of the Virgin Mary and child, attributed to Irish revolutionary, suffragette, actress, and -

The Historic Oliver St. John Gogarty's Temple Bar, Dublin

est. 2006 June 2020 • Volume 14 - Issue 6 The Historic Oliver St. John Gogarty’s Temple Bar, Dublin Inch by Inch, Row by Row SAFE HOME Call TODAY to be a part of the Editor s including those that came to us advertiser driven newsmagazine. You Ohio Irish American News! ’ after we went to print, save-the-date can pick up a print edition at any one Corner items, and things that have spurred of our 211 locations across Ohio, as By John O’Brien, Jr. discussion on our community. well as in Indiana, Kentucky, New June 2020 Vol. 14 • Issue 6 JOHN J. COUGHLIN 216.647.1144 We have launched four episodes York, Pennsylvania and Michigan, Publisher John O’Brien Jr. September 11, 1931 - May 19, 2020 so far and will continue to release for free; you can view any of the Editor John O’Brien Jr. On September 11, 1931, the world was blessed @Jobjr Design/Production Christine Hahn Í the podcasts every other week, social media and website info, the Website Rich Croft@VerticalLift with the gift of John J. Coughlin, Jr. His humor, FULL PAGE BLEED FULL PAGE Half PAGE alternating with our eBulletin, which podcast, our Youtube channel, and Columnists kind-hearted spirit, and Irish charm encompass who 11” WIDE X 12” TALL 9.75”WIDE X 10”TALL 9.75”WIDE X 5”TALL Inch by inch, row by row, has similar stories at times, and the eBulletin, for free, thanks to the Akron Irish Lisa O’Rourke he was. He was a man of great faith and dedication gonna make this garden grow An Eejit Abroad CB Makem immediate info. -

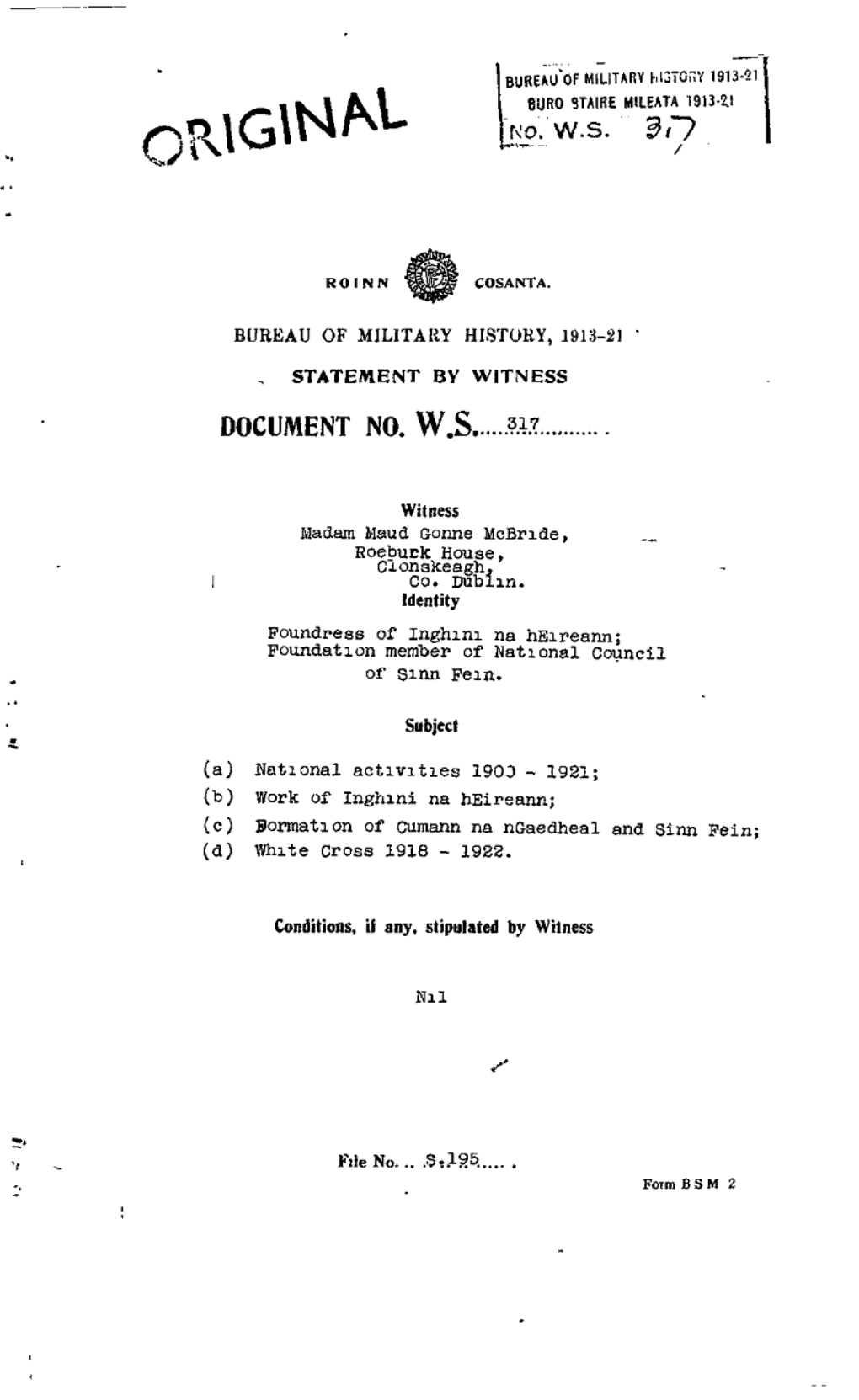

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU of MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT by WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO W.S. Witness Liam De Róiste No. 2 Janemou

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO W.S. Witness Liam de Róiste No. 2 Janemount, Sunday's Well, Cork. Identity. Member, Coiste Gnotha, Gaelic League. Member, Dáil Éireann, 1918-1923. Subject. National Activities, 1899-1918. Irish Volunteers, Cork City, 1913-1918. Conditions,if any, Stipulatedby Witness. Nil. File No FormB.S.M.2 STATSUENT OF LIAM DR ROISTE. CERTIFICATE BY THE DIRECTOR OF THE BUREAU. This statement by Liam de Roiste consists of 385 pages, signed on the last page by him. Owing to its bulk it has not been possible for the Bureau, with the appliances at its disposal. to bind it in one piece, and it has, therefore, for convenience in stitching, been separated into two sections, the first, consisting of pages 1-199, and the other, of pages 200-385, inclusive. The separation into two sections baa no other significance. The break between the two sections occurs in the middle of a sentence, the last words in section I, on page 199, being "should be", and the first in section II, on page 200, being "be forced". A certificate in these terms, signed by me as Director of the Bureau, is bound into each of the two parts. McDunphy DIRECTOR. (M. McDunphy) 27th November, 1957. STATIENT BY LIAM DE R0ISTE 2. Janemount, Sundav's Woll. Cork. This statement was obtained from Mr. de Roiste, at the request of Lieut.-Col. T. Halpin, on behalf of the Bureau of Military History, 26 Westland Row, Dublin. Mr. do Hoists was born in Fountainstown in the Parish of Tracton, Co.