Scott F. Gilbert-Developmental Biology, 9Th Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cleavage of Cytoskeletal Proteins by Caspases During Ovarian Cell Death: Evidence That Cell-Free Systems Do Not Always Mimic Apoptotic Events in Intact Cells

Cell Death and Differentiation (1997) 4, 707 ± 712 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 13509047/97 $12.00 Cleavage of cytoskeletal proteins by caspases during ovarian cell death: evidence that cell-free systems do not always mimic apoptotic events in intact cells Daniel V. Maravei1, Alexander M. Trbovich1, Gloria I. Perez1, versus the cell-free extract assays (actin cleaved) raises Kim I. Tilly1, David Banach2, Robert V. Talanian2, concern over previous conclusions drawn related to the Winnie W. Wong2 and Jonathan L. Tilly1,3 role of actin cleavage in apoptosis. 1 The Vincent Center for Reproductive Biology, Department of Obstetrics and Keywords: apoptosis; caspase; ICE; CPP32; actin; fodrin; Gynecology, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, proteolysis; granulosa cell; follicle; atresia Boston, Massachusetts 02114 USA 2 Department of Biochemistry, BASF Bioresearch Corporation, Worcester, Massachusetts 01605 USA Abbreviations: caspase, cysteine aspartic acid-speci®c 3 corresponding author: Jonathan L. Tilly, Ph.D., Massachusetts General protease (CASP, designation of the gene); ICE, interleukin- Hospital, VBK137E-GYN, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, Massachusetts 1b-converting enzyme; zVAD-FMK, benzyloxycarbonyl-Val- 02114-2696 USA. tel: +617 724 2182; fax: +617 726 7548; Ala-Asp-¯uoromethylketone; zDEVD-FMK, benzyloxycarbo- e-mail: [email protected] nyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-¯uoromethylketone; kDa, kilodaltons; Received 28.1.97; revised 24.4.97; accepted 14.7.97 ICH-1, ICE/CED-3 homolog-1; CPP32, cysteine protease Edited by J.C. Reed p32; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose)-polymerase; MW, molecular weight; STSP, staurosporine; C8-CER, C8-ceramide; DTT, dithiothrietol; cCG, equine chorionic gonadotropin (PMSG or Abstract pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin); ddATP, dideoxy-ATP; kb, kilobases; HEPES, N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N'-(2- Several lines of evidence support a role for protease ethanesulfonic acid); SDS ± PAGE, sodium dodecylsulfate- activation during apoptosis. -

Vertebrate Embryonic Cleavage Pattern Determination

Chapter 4 Vertebrate Embryonic Cleavage Pattern Determination Andrew Hasley, Shawn Chavez, Michael Danilchik, Martin Wühr, and Francisco Pelegri Abstract The pattern of the earliest cell divisions in a vertebrate embryo lays the groundwork for later developmental events such as gastrulation, organogenesis, and overall body plan establishment. Understanding these early cleavage patterns and the mechanisms that create them is thus crucial for the study of vertebrate develop- ment. This chapter describes the early cleavage stages for species representing ray- finned fish, amphibians, birds, reptiles, mammals, and proto-vertebrate ascidians and summarizes current understanding of the mechanisms that govern these pat- terns. The nearly universal influence of cell shape on orientation and positioning of spindles and cleavage furrows and the mechanisms that mediate this influence are discussed. We discuss in particular models of aster and spindle centering and orien- tation in large embryonic blastomeres that rely on asymmetric internal pulling forces generated by the cleavage furrow for the previous cell cycle. Also explored are mechanisms that integrate cell division given the limited supply of cellular building blocks in the egg and several-fold changes of cell size during early devel- opment, as well as cytoskeletal specializations specific to early blastomeres A. Hasley • F. Pelegri (*) Laboratory of Genetics, University of Wisconsin—Madison, Genetics/Biotech Addition, Room 2424, 425-G Henry Mall, Madison, WI 53706, USA e-mail: [email protected] S. Chavez Division of Reproductive & Developmental Sciences, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Department of Physiology & Pharmacology, Oregon Heath & Science University, 505 NW 185th Avenue, Beaverton, OR 97006, USA Division of Reproductive & Developmental Sciences, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Oregon Heath & Science University, 505 NW 185th Avenue, Beaverton, OR 97006, USA M. -

Cleavage: Types and Patterns Fertilization …………..Cleavage

Cleavage: Types and Patterns Fertilization …………..Cleavage • The transition from fertilization to cleavage is caused by the activation of mitosis promoting factor (MPF). Cleavage • Cleavage, a series of mitotic divisions whereby the enormous volume of egg cytoplasm is divided into numerous smaller, nucleated cells. • These cleavage-stage cells are called blastomeres. • In most species the rate of cell division and the placement of the blastomeres with respect to one another is completely under the control of the proteins and mRNAs stored in the oocyte by the mother. • During cleavage, however, cytoplasmic volume does not increase. Rather, the enormous volume of zygote cytoplasm is divided into increasingly smaller cells. • One consequence of this rapid cell division is that the ratio of cytoplasmic to nuclear volume gets increasingly smaller as cleavage progresses. • This decrease in the cytoplasmic to nuclear volume ratio is crucial in timing the activation of certain genes. • For example, in the frog Xenopus laevis, transcription of new messages is not activated until after 12 divisions. At that time, the rate of cleavage decreases, the blastomeres become motile, and nuclear genes begin to be transcribed. This stage is called the mid- blastula transition. • Thus, cleavage begins soon after fertilization and ends shortly after the stage when the embryo achieves a new balance between nucleus and cytoplasm. Cleavage Embryonic development Cleavage 2 • Division of first cell to many within ball of same volume (morula) is followed by hollowing -

Lineage and Fate of Each Blastomere of the Eight-Cell Sea Urchin Embryo

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 5, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Lineage and fate of each blastomere of the eight-cell sea urchin embryo R. Andrew Cameron, Barbara R. Hough-Evans, Roy J. Britten, ~ and Eric H. Davidson Division of Biology, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 91125 USA A fluoresceinated lineage tracer was injected into individual blastomeres of eight-cell sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) embryos, and the location of the progeny of each blastomere was determined in the fully developed pluteus. Each blastomere gives rise to a unique portion of the advanced embryo. We confirm many of the classical assignments of cell fate along the animal-vegetal axis of the cleavage-stage embryo, and demonstrate that one blastomere of the animal quartet at the eight-cell stage lies nearest the future oral pole and the opposite one nearest the future aboral pole of the embryo. Clones of cells deriving from ectodermal founder cells always remain contiguous, while clones of cells descendant from the vegetal plate {i.e., gut, secondary mesenchyme) do not. The locations of ectodermal clones contributed by specific blastomeres require that the larval plane of bilateral symmetry lie approximately equidistant {i.e., at a 45 ° angle) from each of the first two cleavage planes. These results underscore the conclusion that many of the early spatial pattems of differential gene expression observed at the molecular level are specified in a clonal manner early in embryonic sea urchin development, and are each confined to cell lineages established during cleavage. [Key Words: Development; cell lineage; dye injection; axis specification] Received December 8, 1986; accepted December 24, 1986. -

Developmental Patterns: What's a Protostome and a Deuterostome?

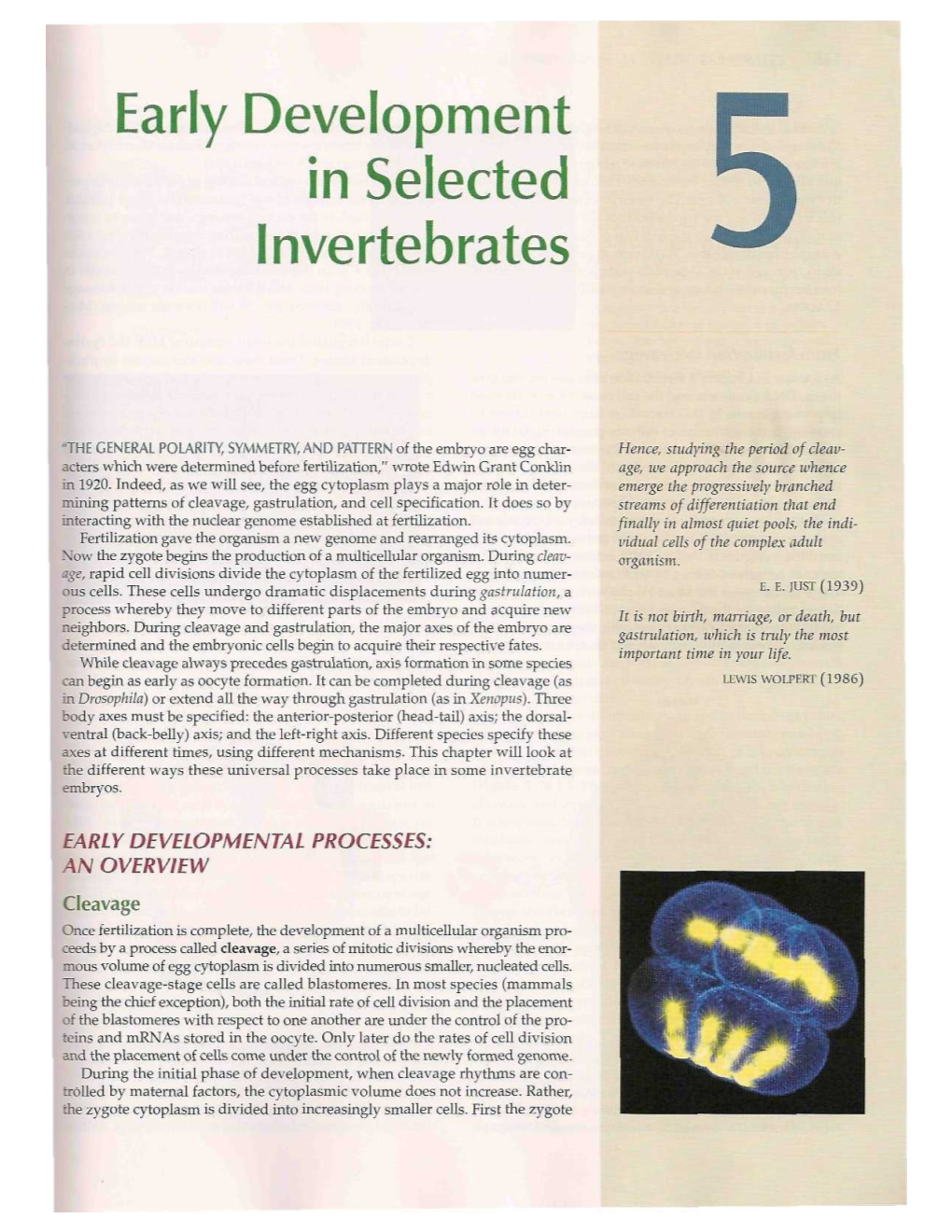

Developmental Patterns: What’s a Protostome and a Deuterostome? Early Development cleavage • Fertilized Egg Blastula reorganization • Blastula Gastrula What Characterizes Cleavage? • Outcome – large egg divided into typical small cells – large increase in number of cells, chromatin, surface membrane • Characteristics – no growth – cell cycle: rapid S, little G1 – shape the same except for cavity (blastocoele) – use of storage reserves (from oogenesis) – embryonic gene activity relatively unimportant Cleavage Patterns I • Holoblastic – complete cleavage • Isolecithal – evenly distributed yolk • Mesolecithal – slight polarization of yolk Cleavage Patterns II • Meroblastic – incomplete division • Telolecithal – more yolk at one end • Centrolecithal – yolk in the center What Characterizes Gastrulation? • Outcome – increase in overt differentiation – morphogenetic changes • Characteristics – slowing of cell division – little if any growth – increasing importance of embryo gene activity – cell movements and rearrangements – establishment of basic body plan In What Ways Do Cells Move? Gastrulation • Common Processes – changes in cell contacts – motility – shape – cell-cell communication – interactions of cells with extracellular matrix – all precise and orderly The Body Plan • Gastrula establishes basic pattern – ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm – primary germ layers primordial organ rudiments – germ layers bring cells to new positions to • self-differentiate in correct spatial relationships • be induced by new neighbors Early Development of Selected -

Cleavage and Gastrulation in Drosophila Embryos

Cleavage and Gastrulation in Introductory article Drosophila Embryos Article Contents . Drosophila’s Unusual Syncytial Blastoderm: an Uyen Tram, University of California, Santa Cruz, California, USA Overview . Fertilization and the Initiation of Mitotic Cycling Blake Riggs, University of California, Santa Cruz, California, USA . Preblastoderm William Sullivan, University of California, Santa Cruz, California, USA . Syncytial Blastoderm and Nuclear Migration . Pole Cell Formation The cytoskeleton guides early embryogenesis in Drosophila, which is characterized by a . The Cortical Divisions and Cellularization series of rapid synchronous syncytial nuclear divisions that occur in the absence of . Rapid Nuclear Division and the Cell Cycle cytokinesis. Following these divisions, individual cells are produced in a process called . Overview of Gastrulation cellularization, and these cells are rearranged during the process of gastrulation to produce . Cell Shape Changes an embryo composed of three primordial tissue layers. Cell Movements . Mitotic Domains Drosophila’s Unusual Syncytial Blastoderm: an Overview and finally cellularize during interphase of nuclear cycle 14. Immediately following completion of cellularization, Like many other insects, early embryonic development in gastrulation is initiated with the formation of the head the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster is rapid and occurs in a and ventral furrows. syncytium. The first 13 nuclear divisions are completed in Space is limited during the syncytial divisions. This just over 3 hours and occur in the absence of cytokinesis, problem is particularly acute during the cortical divisions producing an embryo of some 6000 nuclei in a common when thousands of nuclei are rapidly dividing in a confined cytoplasm. At the interphase of nuclear 14, these nuclei are monolayer. In spite of the crowding, embryogenesis is an packaged into individual cells in a process known as extremely precise process. -

Emerging Roles of Caspase-3 in Apoptosis

Cell Death and Differentiation (1999) 6, 99 ± 104 ã 1999 Stockton Press All rights reserved 13509047/99 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/cdd Review Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis Alan G. Porter*,1 and Reiner U. JaÈnicke1 being crucial for this process in diverse metazoan organisms.3±5 In mammals, caspases (principally cas- 1 Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, The National University of Singapore, pase-3) appear to be activated in a protease cascade that 30 Medical Drive, Singapore 117609, Republic of Singapore leads to inappropriate activation or rapid disablement of key * corresponding author: Alan G. Porter, Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, structural proteins and important signaling, homeostatic and The National University of Singapore, 30 Medical Drive, Singapore 117609, repair enzymes.3 Caspase-3 is a frequently activated death Republic of Singapore; tel: 65 874-3761; fax: 65 779-1117; email: [email protected] protease; however, the specific requirements of this (or any other) caspase in apoptosis were until now largely unknown. Received 23.9.98; revised 5.11.98; accepted 12.11.98 Recent work, reviewed here, has revealed that caspase-3 is Edited by G. Salvesen important for cell death in a remarkable tissue-, cell type- or death stimulus-specific manner, and is essential for some of the characteristic changes in cell morphology and certain Abstract biochemical events associated with the execution and Caspases are crucial mediators of programmed cell death completion of apoptosis. (apoptosis). Among them, caspase-3 is a frequently activated death protease, catalyzing the specific cleavage of many key Caspase-3 is a frequently activated cellular proteins. -

19 Apoptosis Chapter 9 Neelu Yadav Phd [email protected] Why Cells Decide to Die? - Stress, Harmful, Not Needed - Completed Its Life Span

#19 Apoptosis Chapter 9 Neelu Yadav PhD [email protected] Why cells decide to die? - Stress, harmful, not needed - Completed its life span Death stimulation or Stress Cell Survival Death Functions of PCD during Development Involution of the mammary gland after lactation Fuchs and Steller. Cell Volume 147, Issue 4 2011 742 - 758 Types of Cell Death Cell Death Controlled cell death Uncontrolled cell death Physiological cell death or Necrotic cell death (?) Programmed cell death (Type III) Autophagic cell death Apoptotic cell death (Type II) (Type I) Caspase-independent Caspase-dependent Extrinsic pathway Intrinsic pathway (Death receptor-mediated) Types of Cell Death Fink and Cookson, Infect Immun. 2005 Evolutionary Conservation of the Core Apoptotic Machinery Yaron Fuchs , Hermann Steller Cell Volume 147, Issue 4 2011 742 - 758 What is the difference between key cell death mechanisms Apoptosis Autophagy Necrosis -Genetically programmed Genetically programmed Not (?) genetically -Extra and intracellular Extra and intracellular Acute injury (?) (Extra) -Cell shrinkage Autophagic vacuoles Cytoplasm swelling -Blebbing Blebbing Disruption of Memb -Organelle intact Sequesteration Disruption -Chromatin condensation Partial condensation Non-condensed -DNA fragmentation (laddering) No laddering No laddering -Phagocytosis with Phagocytosis with Release of intracellular no inflammation no inflammation contents & inflammation -Caspase-dependent Caspase-independent Caspase-independent What is Apoptosis? - A predominant form of cell death -

Unit 14 Cleavage and Gastrulation

UNIT 14 CLEAVAGE AND GASTRULATION Structure 14.1 Introduction Objectives 14.2 Cleavage Yolk and Cleavage Planes of Cleavage Pattern of Cleavage Roducts of Cleavage (Morula and Blastula) Mechanism of Cleavage 14.3 Gastrulation Fate Maps Morphogenetic Movements Gastrulation*inSome Animals 14.4 Summary 14.5 Terminal Questions 14.6 Answers 14.1 INTRODUCTION In Unit 13 ~f this Block you have studied that spermatozoa reach the ovum by either chance or chemical attraction. Eventually, one spermatozoon fuses wi the ovum to restore the diploid genomic condition and activates all the potentials ir the fertilised egg cell or zygote to develop into a new individual of the next generation. But the zygote is one cell and the adult body in the Metazoa is constituted of many cells - from a few hundred to many billions of cells. It implies that the unicellular zygote must enter the phase of rapid divisions in quick succession to convert itself into a multicellular body. Such a series of divisions of the zygote is known as cleavage or segmentation. In this multicellular structure formed as a result of cleavage the various cells or cell groups later become tearranged as layers and sublayers during a process called gastrulation. Cleavage and gasuulation are significant phases in the ontogenetic development because cleavage transforms the unicellular zygote into a mullicellular body and gastrulation lays the foundation of primary organ rudiments so as to initiate the formation of organs according to the body plan of the particular metazoan group of animals to which the particular individual belongs. 0 bjectives After you have read this unit you should be able to: explain the various planes of cleavage furrows . -

Developmental Biology B.Sc. Biotechnology 4Th Semester (Generic Elective) Unit-II Early Embryonic Development Unit-II Reference Notes

INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL TRIBAL UNIVERSITY AMARKANTAK, M.P. 484886 SUBJECT- Biotechnology TITLE- Developmental Biology B.Sc. Biotechnology 4th Semester (Generic Elective) Unit-II Early Embryonic Development Unit-II Reference Notes Dr. Parikipandla Sridevi Assistant Professor Dept. of Biotechnology Faculty of Science Indira Gandhi National Tribal University Amarkantak, MP, India Pin: 484887 Mob No: +919630036673, +919407331673 Email Id: [email protected], [email protected] [email protected] Unit II UNIT II: Early embryonic development Cleavage: Definition, types, patterns & mechanism Blastulation: Process, types & mechanism, Gastrulation: Morphogenetic movements– epiboly, emboly, extension, invagination, convergence, de-lamination. Formation & differentiation of primary germ layers, Fate Maps in early embryos. CONTENTS 1. Cleavage: types, pattern & mechanism 2. Blastulation- types & mechanism 3. Gastrulation: Morphogenetic movements 4. Germ layers & fate maps in early embryos 1. CLEAVAGE: types, pattern & mechanism The process of cleavage remains one of the earliest mechanical activity in the conversion of a single celled egg into a multicellular embryo. It is initiated by the sperm during fertilization. However, in parthenogenetic eggs cleavage can commence without the influence of fertilization. The process of cleavage or cellulation happens through repeated mitotic divisions. These divisions result in cells called blastomeres. In later stages of development, the blastomeres occupy different regions and differentiate into several types of body cells. The first cleavage of frog’s egg was observed by Swammerdam in 1738. The entire process of cleavage in frog’s egg was studied by Prevost and Dumas in 1824. With the development of microscopes cleavages and further stages were observed in the eggs of sea urchin, star fishes, amphioxus and hen’s eggs. -

Early Development I: Cleavage

Early Development I: Cleavage Lecture Outline Four Major Developmental Events The Timing of Early Development Cleavage: Functions and Events Mitotic vs Normal Cell Cycle The Purposes of Cleavage The Stages of Early Cleavage Cleavage, Compaction, Blastocyst Formation and Hatching Mammalian Compaction What is E-Cadherin? Cadherin & Compaction Formation of the Blastocyst Hatching of the Blastocyst References Four Major Developmental Events There are 4 major developmental processes that occur in human embryogenesis. Cell Division (Cleavage) - Converts 1 cell to many; the egg is one cell, the embryo is multicellular; the conversion from one cell into many involves an initial cleavage (embryonic mitoses) phase followed by regular mitotic cell divisions. Cell Differentiation - formation of different, specialized cell types; the egg is one cell type, the embryo contains hundreds of cell types; understanding how cells specialize is a fundamental problem of developmental biology Morphogenetic Events - literally the "generation of shape", morphogenesis results in the embryonic organization, the pattern & polarity to cells, organs & tissues; the egg is round while the embryo has a specific organization of multiple layers of different cells; the terms morphogenesis and differentiation are not synonymous although many researchers today make this mistake in terminology; cell differentiation is just one component of morphogenesis Growth - Increases size of organism; the embryo increases dramatically in size from the next to invisible egg to the full grown fetus. Of course there are other component events that also occur such as apoptosis (controlled cell death) which underlies many morphogenetic events in the formation of tissues and organs. Apoptosis was discussed earlier in the course. The Timing of Early Development As we work through early development over the next several lectures you should have a basic idea of when specific events occur. -

Development of Amphioxus Upto Formation of Coelom

Development of Amphioxus Upto the formation of Coelom SHUSHMA KUMARI HOD & Assistant Professor, Zoology J. D. women’s College Patna BSC (Zoology) – Part II INTRODUCTION Amphioxus, plural amphioxi, or amphioxuses, also called lancelet, any of certain members of the invertebrate subphylum Cephalochordata of the phylum Chordata. Amphioxi are small marine animals found widely in the coastal waters of the warmer parts of the world and less commonly in temperate waters. Both morphological and molecular evidence show them to be close relatives of the vertebrates. • Development of amphioxus is indirect involving a larval stage. • The early embryology of Amphioxus is simple and straightforward. • The early development of Amphioxus is of great phylogenetic significance because it resembles with those of invertebrates like Echinodermates on one hand and vertebrates on other hand. • Development of Amphioxus was described by many scientists viz., Hatscheck (4882, 1888), Wilson (1983), Cerfontaine (1906) and Conklin (1932). • The work of Conklin is most recent and accepted one. Fertilizaion • Fertilization is external, taking place in the surrounding seawater where eggs and spermatozoa areshed. • Before fertilization, the ovum has an outer thin vitellinemembrane, enclosing a peripheral cytoplasmic layer, central yolky cytoplasm mainly towards the vegetal pole and a fluid filled germinal sac or nucleus towards the animalpole. • During fertilization the sperm enters the egg near the vegetalpole. PresumptiveArea Cleavage andBlastulation • The cleavage of eggs is Holoblastic and is of Equaltype. • Thefirstcleavageis Meridional,i.e. oriented alongthe median axisfrom animal to vegetal pole. • Theresult of cleavageis the formation of two identical blastomeres establishing the bilateral symmetry of the adultanimal. • TheSecondcleavageis also oriented from animal to vegetal pole but at right angleto the first and divides the first two blastomeres into4 equal sized cells • The third cleavage is horizontal (transverse) and slightly above the equatorial region.