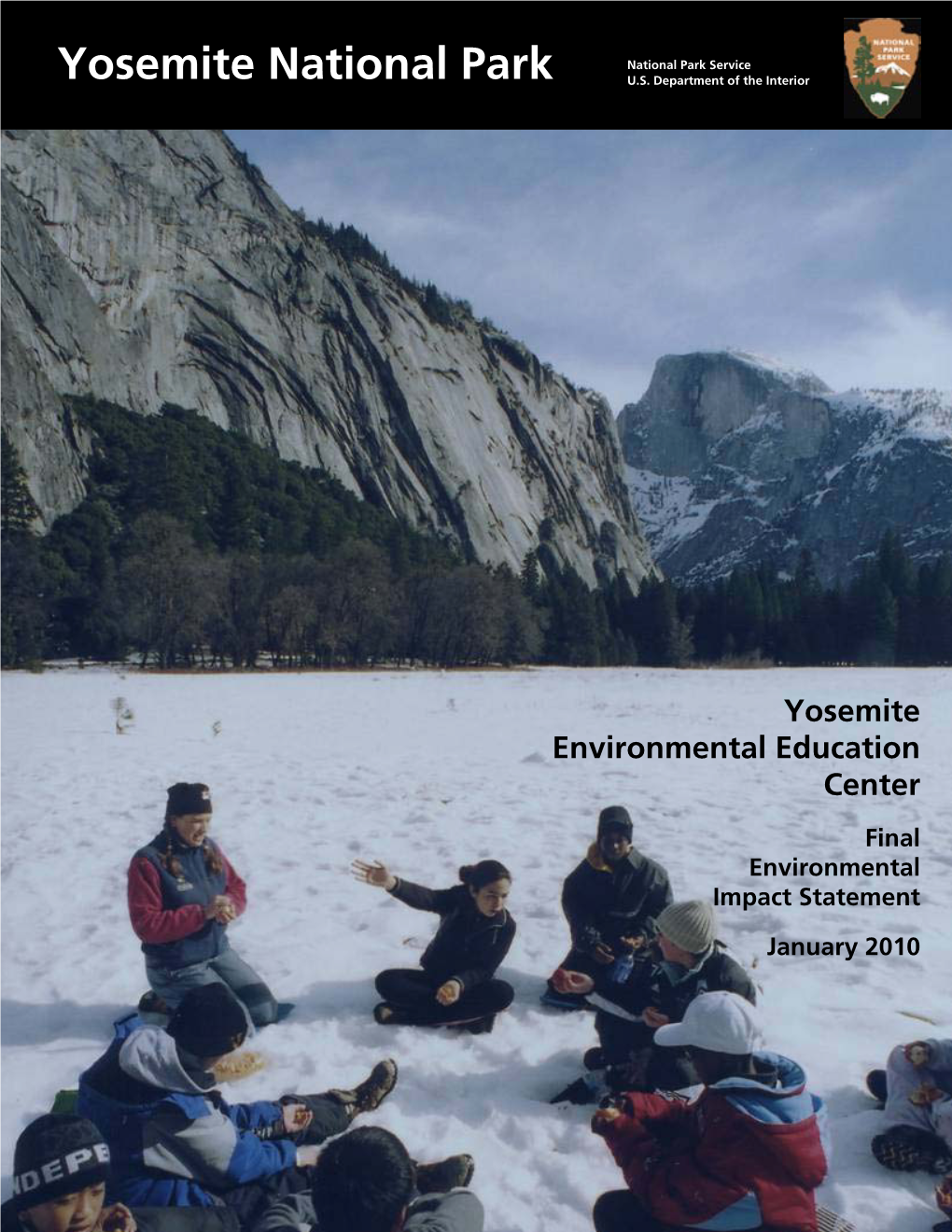

Yosemite Environmental Education Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK O C Y Lu H M Tioga Pass Entrance 9945Ft C Glen Aulin K T Ne Ee 3031M E R Hetc C Gaylor Lakes R H H Tioga Road Closed

123456789 il 395 ra T Dorothy Lake t s A Bond C re A Pass S KE LA c i f i c IN a TW P Tower Peak Barney STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST Mary Lake Lake Buckeye Pass Twin Lakes 9572ft EMIGRANT WILDERNESS 2917m k H e O e O r N V C O E Y R TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST N Peeler B A Lake Crown B C Lake Haystack k Peak e e S Tilden r AW W Schofield C TO Rock Island OTH IL Peak Lake RI Pass DG D Styx E ER s Matterhorn Pass l l Peak N a Slide E Otter F a Mountain S Lake ri e S h Burro c D n Pass Many Island Richardson Peak a L Lake 9877ft R (summer only) IE 3010m F LE Whorl Wilma Lake k B Mountain e B e r U N Virginia Pass C T O Virginia S Y N Peak O N Y A Summit s N e k C k Lake k c A e a C i C e L C r N r Kibbie d YO N C n N CA Lake e ACK AI RRICK K J M KE ia in g IN ir A r V T e l N k l U e e pi N O r C S O M Y Lundy Lake L Piute Mountain N L te I 10541ft iu A T P L C I 3213m T Smedberg k (summer only) Lake e k re e C re Benson Benson C ek re Lake Lake Pass C Vernon Creek Mount k r e o Gibson e abe Upper an r Volunteer McC le Laurel C McCabe E Peak rn Lake u Lake N t M e cCa R R be D R A Lak D NO k Rodgers O I es e PLEASANT EA H N EL e Lake I r l Frog VALLEY R i E k G K C E LA e R a e T I r r Table Lake V North Peak T T C N Pettit Peak A INYO NATIONAL FOREST O 10788ft s Y 3288m M t ll N Fa s Roosevelt ia A e Mount Conness TILT r r Lake Saddlebag ILL VALLEY e C 12590ft (summer only) h C Lake ill c 3837m Lake Eleanor ilt n Wapama Falls T a (summer only) N S R I Virginia c A R i T Lake f N E i MIGUEL U G c HETCHY Rancheria Falls O N Highway 120 D a MEADOW -

Yosemite Valley Hiking Map U.S

Yosemite National Park National Park Service Yosemite Valley Hiking Map U.S. Department of the Interior To To ) S k Tioga n Tioga m e To o e k w r Road 10 Shuttle Route / Stop Road 7 Tioga . C Ranger Station C 4 n 3.I mi (year round) 6.9 mi ( Road r e i o 5.0 km y I e II.I km . 3.6 mi m n 6 k To a 9 m 5.9 km 18 Shuttle Route / Stop . C Self-guiding Nature Trail Tioga North 0 2 i Y n ( . o (summer only) 6 a Road 2 i s . d 6 m e 5.0 mi n m k i I Trailhead Parking ( 8.0 km m Bicycle / Foot Path I. it I.3 0 e ) k C m (paved) m re i ( e 2 ) ) k . Snow I Walk-in Campground m k k m Creek Hiking Trail .2 k ) Falls 3 Upper e ( e Campground i r Waterfall C Yosemite m ) 0 Fall Yosemite h I Kilometer . c r m 2 Point A k Store l 8 6936 ft . a ) y 0 2II4 m ( m I Mile o k i R 9 I. m ( 3. i 2 5 m . To Tamarack Flat North m i Yosemite Village 0 Lower (5 .2 Campground . I I Dome 2.5 mi Yosemite k Visitor Center m 7525 ft 0 Fall 3.9 km ) 2294 m . 3 k m e Cre i 2.0 mi Lower Yosemite Fall Trail a (3 To Tamarack Flat ( Medical Royal Mirror .2 0 y The Ahwahnee a m) k . -

Yosemite Guide @Yosemitenps

Yosemite Guide @YosemiteNPS Yosemite's rockclimbing community go to great lengths to clean hard-to-reach areas during a Yosemite Facelift event. Photo by Kaya Lindsey Experience Your America Yosemite National Park August 28, 2019 - October 1, 2019 Volume 44, Issue 7 Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Summer-only Route: Upper Hetch Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Hetchy Shuttle Fall Yosemite Tuolumne Village Campground Meadows Lower Yosemite Parking The Ansel Fall Adams Yosemite l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area Picnic Area Valley l T Area in inset: al F e E1 t 5 Restroom Yosemite Valley i 4 m 9 The Ahwahnee Shuttle System se Yo Mirror Upper 10 3 Walk-In 6 2 Lake Campground seasonal 11 1 Wawona Yosemite North Camp 4 8 Half Dome Valley Housekeeping Pines E2 Lower 8836 ft 7 Chapel Camp Yosemite Falls Parking Lodge Pines 2693 m Yosemite 18 19 Conservation 12 17 Heritage 20 14 Swinging Center (YCHC) Recreation Campground Bridge Rentals 13 15 Reservations Yosemite Village Parking Curry Upper Sentinel Village Pines Beach il Trailhead E6 a Curry Village Parking r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M E4 ey ses erce all only d Ri V ver E5 Nevada Fall To & Bridalveil Fall d oa R B a r n id wo a a lv W e i The Yosemite Valley Shuttle operates from 7am to 10pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Yosemite Valley Visitor Center

k e k e e r e C r Upper C n Yosemite o h y c r Fall n k A a e C e l r Yosemite Point a n C 6936ft y a Lower o 2114m i North Dome e d R t 7525ft i Yosemite n I 2294m m Fall e s ek o re Y U.S. Yosemite Valley Visitor Center C ya Court a Wilderness Center n e Museum Royal Arch T Lower Yosemite Medical Clinic Cascade Fall Trail Washington Columbia YOSEMITE Column Mirror Rock VILLAGE ROYAL Eagle Lake T ARCHES 4094ft Peak H 1248m 7779ft R The Ahwahnee Half Dome 2371m Sentinel Visitor E 8836ft Bridge Parking E North 2693m B Housekeeping Pines Camp 4 R Yosemite Camp Lower O Lodge Pines Chapel Stoneman T Bridge Middle H LeConte Brother E Memorial Road open ONLY to R Lodge pedestrians, bicycles, Ribbon S Visitor Parking and vehicles with Fall Swinging Bridge Curry Village Upper wheelchair emblem Pines Lower placards Sentinel Little Yosemite Valley El Capitan Brother Beach Trailhead for Moran 7569ft Four Mile Trail (summer only) R Point Staircase Mt Broderick i 2307m Trailhead 6706ft 6100 ft b Falls Horse Tail Parking 1859m b 2044m o Fall Trailhead for Vernal n Fall, Nevada Fall, and Glacier Point El Capitan Vernal C 7214 ft Nature Center John Muir Trail r S e e 2199 m at Happy Isles Fall Liberty Cap e n r k t 5044ft 7076ft ve i 4035ft Grizzly Emerald Ri n rced e 1230m 1538m 2157m Me l Peak Pool Silver C Northside Drive ive re Sentinel Apron Dr e North one-way Cathedral k El Capitan e Falls 0 0.5 Kilometer id To Tioga Road, Tuolumne Meadows Bridge Beach hs y ed R ut a y J and Hwy 120; and Hetch Hetchy Merc iv So -w horse trail onl o 0 0.5 Mile er -

Yosemite Forest Dynamics Plot

REFERENCE COPY - USE for xeroxing historic resource siuay VOLUME 3 OF 3 discussion of historical resources, appendixes, historical base maps, bibliography YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK / CALIFORNIA Historic Resource Study YOSEMITE: THE PARK AND ITS RESOURCES A History of the Discovery, Management, and Physical Development of Yosemite National Park, California Volume 3 of 3 Discussion of Historical Resources, Appendixes, Historical Base Maps, Bibliography by Linda Wedel Greene September 1987 U.S. Department of the Interior / National Park Service b) Frederick Olmsted's Treatise on Parks ... 55 c) Significance of the Yosemite Grant .... 59 B. State Management of the Yosemite Grant .... 65 1. Land Surveys ......... 65 2. Immediate Problems Facing the State .... 66 3. Settlers' Claims ........ 69 4. Trails ........%.. 77 a) Early Survey Work ....... 77 b) Routes To and Around Yosemite Valley ... 78 c) Tourist Trails in the Valley ..... 79 (1) Four-Mile Trail to Glacier Point ... 80 (2) Indian Canyon Trail ..... 82 (3) Yosemite Fall and Eagle Peak Trail ... 83 (4) Rim Trail, Pohono Trail ..... 83 (5) Clouds Rest and Half (South) Dome Trails . 84 (6) Vernal Fall and Mist Trails .... 85 (7) Snow Trail ....... 87 (8) Anderson Trail ....... (9) Panorama Trail ....... (10) Ledge Trail 89 5. Improvement of Trails ....... 89 a) Hardships Attending Travel to Yosemite Valley . 89 b) Yosemite Commissioners Encourage Road Construction 91 c) Work Begins on the Big Oak Flat and Coulterville Roads ......... 92 d) Improved Roads and Railroad Service Increase Visitation ......... 94 e) The Coulterville Road Reaches the Valley Floor . 95 1) A New Transportation Era Begins ... 95 2) Later History 99 f) The Big Oak Flat Road Reaches the Valley Floor . -

Yosemite Nature Notes

Yosemite Nature Notes VOL. XXX SEPTEMBER, 1951 NO. 9 82 YOSEMITE-NATURE_NOTES Sugar pines in Yosemite National Park Cover Photo : Aerial vi ew of Yosemite Valley and the Yosemite high Sierra . Made and donated to Yosemite Museum by Mr. Clarence Srock of Aptos, California . See back cover for outline index chgrt . Yosemite Nature Notes THE MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF THE YOSEMITE NATURALIST DIVISION AND THE YOSEMITE NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION, INC. C . P. Russell, Superintendent P . E . McHenry, Park Naturalist H . C . Parker, Assoc. Park Naturalist N . B . Herkenham, Asst. Park Naturalist W. W . Bryant, Junior Park Naturalist VOL. XXX SEPTEMBER, 1951 NO. 9 YOSEMITE'S PIONEER ARBORETUM By O. L. Wallis, Park Ranger A pioneer attempt to "interpret" quarters was established at Camp the botanical features of Yosemite A . E. Wood near Wawona. Major National Park for its visitors was the Bigelow, Ninth Cavalry, was the act- establishment of the arboretum near ing superintendent. Wawona in 1904 by Maj . John Bige- It is apparent from his reports of low, Jr. This was 16 years before 1904 that the major was deeply in- Dr . Harold C. Bryant initiated the terested in all natural history, but nature-guiding service in . Yosemite, especially did he enjoy trees. He the nucleus of the present naturalist wrote that the forest reservation of interpretive program for the entire Yosemite had the following purposes: National Park Service . To provide a great museum of nature for the general public tree of cost . To preserve Evidences of this arboretum and not only trees, but everything that is associ- botanical garden can still be found ated with them in nature ; not only the sylva, along the banks of the South Fork but also the flora and tauna, the animal life, and Inc mineral and geological features of the of the Merced River, across from the country comprised to the park. -

BEDROCK GEOLOGY of the YOSEMITE VALLEY AREA YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA Prepared by N

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I-1639 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF THE YOSEMITE VALLEY AREA YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA Prepared by N. King Huber and Julie A. Roller From the writings of Frank C. Calkins and other sources PREFACE INTRODUCTION Frank Calkins' work in Yosemite was preceded by Yosemite Valley, one of the world's great natural works Henry W. Turner, also of the U.S. Geological Survey, of rock sculpture, is carved into the west slope of the who began mapping the Yosemite and Mount Lyell 30- Sierra Nevada. Immense cliffs, domes, and waterfalls minute quadrangles in 1897 and laid the foundation that tower over forest, meadows, and a meandering river, Calkins' work was built on. Although Turner never creating one of the most scenic natural landscapes in completed this sizable assignment, he recognized the North America (fig. 1). In Yosemite Valley and the differing types of plutonic rocks and, for example, named adjoining uplands, the forces of erosion have exposed, the El Capitan Granite. with exceptional clarity, a highly complex assemblage of Calkins mapped the valley and adjacent areas of granitic rocks. The accompanying geologic map shows the Yosemite National Park during the period 1913 through distribution of some of the different rocks that make up 1916, at the same time that Francois Matthes was this assemblage. This pamphlet briefly describes those studying the glacial geology of Yosemite. Calkins rocks and discusses how they differ, both in composition summarized the bedrock geology of part of Yosemite in and structure, and the role they played in the evolution the appendix of Matthes' classic volume "Geologic History of the valley. -

Glacier Point Area Hiking Map U.S

Yosemite National Park National Park Service Glacier Point Area Hiking Map U.S. Department of the Interior 2.0 mi (3.2 k To m 3.1 ) Clouds Rest m i (5 3.8 mi .0 0 k . 5.8 km m) 1 7 . Half 1 m cables Dome ) k i km m 8836ft 0.5 .1 (permit mi i (3 2693m required) m 0 1.9 .8 km ) Glacier Point m For Yosemite Valley trails and information, k r 1 . e 2 v i (7 ( m .7 i 8 km i Bunnell please see the Yosemite Valley Hiking Map. 4. ) R m d Point 3 Four Mile . e 1 c r Trailhead ) e at Road km M Fl ) 0.8 k 7214ft Happy Isles km 6.7 mi (1 a .6 O 2199m Trailhead (1 mi g 1 0 i .0 Vernal Fall 1. B Roosevelt m 1 i Point .6 k Little Yosemite Valley 7380ft m 2250m 6100ft Nevada Fall 0.4 mi 1859m 120 ) 0.6 km Sentinel m Road Trail 1 k ) . m k Crane Flat Dome 4 .2 1.0 mi 4 (4 . Wawona Tunnel 8122ft m i Bridalveil Fall 1 m 1.6 km ( i Tunnel 6 2476m i ( . Parking Area Ranger Station 2 2 m View . d Washburn 3 9 a . k 0.7 mi 0 Point m o Inspiration km) (3.9 mi 2.4 1.1 km Telephone Campground Taft Point ) R Point 7503ft l Illilouette Fall 3 Illilouette Ridge a .7 m 2287m Store Restrooms t i (6 r .0 1.1 mi (1.8 km) o k Sentinel Dome r ) m Stanford m P k e ) & Taft Point 2 Point 0 . -

The Archaeology of the Cahokia Mounds ICT-II: Site Structure

The Archaeology of the Cahokia Mounds ICT-II: Site Structure James M. Collins fU Mound 72 Illinois Cultural Resources Study No. 10 Illinois Historic Preservation Agency JLUNOIS HISTORICAL SURVEY The Archaeology of the Cahokia Mounds ICT-II: Site Structure James M. Collins 1990 Illinois Cultural Resources Study No. 10 Illinois Historic Preservation Agency Springfield THE CULTURAL RESOURCES STUDY SERIES The Cultural Resources Study Series was designed by the Illinois State Historic Preservation Office and Illinois Historic Preservation Agency to provide for the rapid dissemination of information to the professional community on archaeological investigations and resource management. To facilitate this process the studies are reproduced as received. Cultural Resources Study No. 10 reports on the features and structural remains excavated at the Cahokia Mounds Interpretive Center Tract-II. The author provides detailed descriptions and interpretations of household and community patterns and their relationship to the evolution of Cahokia 's political organization. This repwrt is a revised version of a draft previously submitted to the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. The project was funded by the Illinois Department of Conservation and, subsequently, by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. William 1. Woods served as Principal Investigator. The work reported here was financed in part with federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of the Interior and administered by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of the Interior or the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Funds for preparation of this report were provided by a grant from The University of Iowa, Office of the Vice President for Research. -

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

@YosemiteNPS Yosemite Guide Yosemite Photo by Christine Loberg Loberg Christine by Photo Yosemite National Park June 21, 2017 – July 25, 2017 Volume 42, Issue 5 Issue 42, Volume 2017 25, July – 2017 21, June Park National Yosemite America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Summer-only Route: Upper Shuttle System El Capitan Yosemite Shuttle Hetch Fall Yosemite Hetchy Village Campground Tuolumne Lower Yosemite Parking Meadows The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area Picnic Area l T al F Yosemite e 5 t E1 Restroom i 4 Valley m 9 The Majestic Area in inset: se Yo Mirror Yosemite Valley Upper 10 3 Yosemite Hotel Walk-In 6 2 Lake Shuttle System seasonal Campground 11 1 Yosemite North Camp 4 8 Half Dome Valley Housekeeping Pines E2 Lower 8836 ft 7 Chapel Camp Wawona Yosemite Falls Parking Lodge Pines 2693 m Yosemite 18 19 Conservation 12 17 Heritage 20 14 Swinging Center (YCHC) Recreation Campground Bridge Rentals 13 Reservations Yosemite Village Parking 15 Pardon our dust! Shuttle service routes are Half Dome Upper Sentinel Village Pines subject to change as pavement rehabilitation Beach il Trailhead E7 a Half Dome Village Parking and road work is completed throughout 2017. r r T te Parking e n il i Expect temporary delays. w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr E4 op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d Ri V ver E6 Nevada Fall To & Bridalveil Fall d oa R B a r n id wo a Wa lv e The Yosemite Valley Shuttle operates from 7am to 10pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Excavations at Four Archeological Sites on the Cnm Rio Rancho Campus, Sandoval County, New Mexico

EXCAVATIONS AT FOUR ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE CNM RIO RANCHO CAMPUS, SANDOVAL COUNTY, NEW MEXICO Alexander Kurota, Patrick Hogan, Brian Cribbin, and F. Scott Worman Office of Contract Archeology University of New Mexico EXCAVATIONS AT FOUR ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE CNM RIO RANCHO CAMPUS, SANDOVAL COUNTY, NEW MEXICO by Alexander Kurota, Patrick Hogan, Brian Cribbin, and F. Scott Worman With Contributions from Connie Constan, Robin M. Cordero, David Holtkamp, Darden Hood, Douglas Rocks-Macqueen, and Pamela J. McBride Prepared for Central New Mexico Community College Dan L. Pearson CNM Facilities Planning 901 Buena Vista Drive SE Albuquerque, NM 87106 (505) 224-4580; Fax (505) 224-4566 Submitted by Patrick Hogan Principal Investigator Report Production by Donna K. Lasusky Graphics by Ronald Stauber, Adrienne Actis, and David Holtkamp Office of Contract Archeology MSC07 4230 1 University of New Mexico 1717 Lomas Blvd. NE Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001 Tel: (505) 277-5853; Fax: (505) 277-6726 NMCRIS No. 116136 OCA/UNM Project No. 185-992 February 2010 ii ABSTRACT This report documents the results of archeological data recovery and construction monitoring at four archeological sites located on the Central New Mexico (CNM) campus in Rio Rancho, Sandoval County, New Mexico. The work was performed by the Office of Contract Archeology, University of New Mexico (OCA/UNM) as a follow-up project to the Class III OCA survey of the 40-acre parcel of CNM-owned land. That survey documented six archeological sites and 12 Isolated Occurrences. Four of the sites, including LA 158640, and LA 158641, were recommended as eligible for the nomination to the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion “d” of 36 CFR 60.4. -

CANOEING for CONNECTION Ii

Canoe Tripping as a Context for Connecting with Nature: A Case Study Mira Freiman Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the M.A. in Education Faculty of Education University of Ottawa © Mira Freiman, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 CANOEING FOR CONNECTION ii Acknowledgments Thanks first and foremost to my participants. I could not have done this without you but also, thanks for making it so much fun. Thanks to Mark who shares in, and celebrates my connection with nature, and who has supported this project since the beginning. Thanks to Mumsy, Daddy and Ariel who have supported me always and have recognized my love for nature since my beginning. Thanks to Grits for my happy Tuesday afternoons, Sabina who always fills me with hope and peace, Margaux for our chats and Holly for her quiet mind. Thanks to Camp Deep Waters: As a people, you are my community; as an idea, you impassion every aspect of my life; as a place, you are my home. Every single friend I’ve made there; camper, administrator, leader, director, maintenance person and cook alike; has informed these pages. Thanks to Professor Giuliano Reis. It was in your class that I first realized my passion for teaching connection with nature for environmental education. Since that time, and throughout this journey, you have been patient and generous. You have listened to my ideas and made sense of them when I could not. You have shared resources and enthusiasm. This is all so very much appreciated. Your guidance has been invaluable.