View / Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research. Internships. Study Away. Experiential Learning

RISE AT OBERLIN RESEARCH. INTERNSHIPS. STUDY AWAY. EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING. WAYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES MAJORS RISE RESEARCH: • The Karanis Housing Project: An Interactive Map of the University of Michigan Excavations at Karanis, Egypt • Documenting Oberlin’s Indigenous Arctic Ethnology Collection • Hydrology and Terracing in the Monte Pallano Area of Abruzzo, Italy • Mapping Mikt’sqaq Angayuk: A GIS Analysis of a Nineteenth-Century Sod House • The Role of Millet in Pre-Roman Italy INTERNSHIPS: • University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology • Denver Museum of Nature and Science • Historic Annapolis Lost Towns Project • Museum intern, South County History Center, Rhode Island STUDY AWAY: • Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies in Rome • University College London Institute of Archaeology • Oberlin-in-London 2019: Earth Science and Material Culture • The School for Field Studies, Tropical Island Biodiversity Studies, Panama EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING: • Archaeological Field Schools through the Institute for Field Research (IFR) • Oberlin Archaeology Society (student club) • Collections research opportunities with the Oberlin College Ethnographic Collection, Oberlin Near East Study Collection, Allen Memorial Art Museum, and Terrell Library Special Collections • Oberlin College-College of Wooster chapter of the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) (2 major annual lectures) FIRST DESTINATIONS OF RECENT ARCHAEOLOGY MAJORS: • Graduate School: PhD programs in archaeology or anthropology at Brown University; University -

September 28, 1995

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange The Kenyon Collegian College Archives 9-28-1995 Kenyon Collegian - September 28, 1995 Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian Recommended Citation "Kenyon Collegian - September 28, 1995" (1995). The Kenyon Collegian. 484. https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian/484 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College Archives at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kenyon Collegian by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume Cxxm, Number 3 E.lIJblished 1856 Tbunday, SepL 28, 1995 Sign theft signals. isolated homophobia By Gianna Maio isahisloryofbomopbobicaetivity ably fn-year SlUdenIS who aren't vandalism. According 10 Man Kenyonasaferenvironmenl They Managing Editor at KcnYOO.and say~ "Signs last ready to deal with these issues at Lavine '97. house manager of areplanning todisUibule mae safe ::-==-===---- .yearwao _dowa.Then: is a coDege," she says. Bauman is a CaplesclcnniuJly.gmfliIi waSwril- wne signs during Coming Out RCCCDt incidents of bislOry of vandalism here.. resident advisor in McBride resi- ee 00 Ibe eIev_ wall of Caples Week, and wid .... be distribut- homophobisCCll>COrllilliSafezane BoIh Bawnan and Kyk>eile dence.buthas_ooproblems eartier Ibis week rdaling 10 receer ing tbem in the dining halls in the signsoo campus baveapia SIim>d Ibe gcoI of Ibe signsas being a way with the signs on her hall. homophobic lellsions 011 campus. nosrfunoe. debaIe as to whether Kcayon Col- 10 cducaIc the community IDlIIO Andy Rkhmond '96. -

Kalamazoo College W.E. Upjohn Center for the Study Of

This digital document was prepared for Kalamazoo College by the W.E. Upjohn Center for the Study of Geographical Change a division of Western Michigan University College of Arts and Sciences COPYRIGHT NOTICE This is a digital version of a Kalamazoo College yearbook. Kalamazoo College holds the copyright for both the paper and digital versions of this work. This digital version is copyright © 2009 Kalamazoo College. All rights reserved. You may use this work for your personal use or for fair use as defined by United States copyright law. Commercial use of this work is prohibited unless Kalamazoo College grants express permission. Address inquiries to: Kalamazoo College Archives 1200 Academy Street Kalamazoo, MI 49006 e-mail: [email protected] .Ko\aVV\ti.XOO Co\\ege. ~a\C\mazoo \ V'f\~c."'~g~V\ Bubbling over, Steaming hot Our Indian name t-Jolds likely as not: Kalamazoo Is a Boiling Pot, Where simmering waters Slowly rise, Then nearly burst The cauldron's sides ; And where, after all, The aim and dream Bubbling, all in a turmoil, unquestionably alive, Is sending the lukewarm the Kalamazoo Coll ege program in the academic Up in steam. year 1963-64 has resembled nothing so much as M. K. a great cauldron of simmering water coming to a rolling boil. Much of the credit for this new energy and activity belongs to President Weimer K. Hicks, to whom, in this tenth year of his asso ciation with the College, this edition of the Boiling Pot is dedicated. MCod~m \ cs ACt '\Vi ti ~s Dff Cam?V0 Sports 0e\\\OrS \Jr\der c\o~~J\\e,r\ Summer Summer employment for caption writers. -

Kenyon Collegian Archives

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange The Kenyon Collegian Archives 10-18-2018 Kenyon Collegian - October 18, 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian Recommended Citation "Kenyon Collegian - October 18, 2018" (2018). The Kenyon Collegian. 2472. https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian/2472 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kenyon Collegian by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESTABLISHED 1856 October 18, 2018 Vol. CXLVI, No.8 Former SMAs create new group after losing confidentiality DEVON MUSGRAVE-JOHNSON SMA Program. In response, some of changes to the SMA program that SMAs would fall into the category support to peer education,” SPRA EDITOR-IN-CHIEF former SMAs have created a new included the discontinuation of the of mandated reporter, which means wrote in an email to the Collegian. support organization: Sexual Re- 24-hour hotline and the termination that the group could no longer have “While peer education is important, On Oct. 8, Talia Light Rake ’20 spect Peer Alliance.” of their ability to act as a confidential legal confidentiality and that the we recognize that there is a great need sent a statement through student Just a day before the letter was resource for students. Beginning this school could be held liable for infor- for peer support on this campus. We email titled “An Open Letter from released to the public, 16 of the 17 year, SMAs were required to file re- mation relayed to the SMAs. -

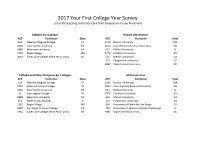

2017 Your First College Year Survey List of Participating Institutions and Their Comparison Group Placement

2017 Your First College Year Survey List of Participating Institutions and their Comparison Group Placement Catholic 4yr Colleges Private Universities ACE Institution State ACE Institution State 354 Albertus Magnus College CT 1145 Boston University MA 2266 Holy Family University PA 2053 Case Western Reserve University OH 5888 Neumann University PA 631 DePaul University IL 1187 Regis College MA 1773 Fordham University NY 2944 Silver Lake College of the Holy Family WI 525 Mercer University GA 172 Pepperdine University CA 1987 Wake Forest University NC Catholic and Other Religious 4yr Colleges All Universities ACE Institution State ACE Institution State 354 Albertus Magnus College CT 1145 Boston University MA 2753 Green Mountain College VT 2053 Case Western Reserve University OH 2266 Holy Family University PA 631 DePaul University IL 8 Huntingdon College AL 1773 Fordham University NY 5888 Neumann University PA 525 Mercer University GA 674 North Central College IL 172 Pepperdine University CA 1187 Regis College MA 260 University of California-San Diego CA 8307 San Diego Christian College CA 704 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign IL 2944 Silver Lake College of the Holy Family WI 1987 Wake Forest University NC Public/Private Universities, Private Nonsectarian 4yr Colleges - Very High Selectivity Public 4yr Colleges ACE Institution State ACE Institution State 1141 Babson College MA 1145 Boston University MA 1749 Colgate University NY 2053 Case Western Reserve University OH 1947 Elon University NC 631 DePaul University IL 1776 Hamilton -

Wallies Prepare to 'Bleed for the Bell'

FOOTBALL KEEPS ROLLING SEE PAGE SIX NOVEMBERAUGUST 30, 1, 2019 2019 Wabash Mourns Bulger ’19 and Seymour H’78 COURTESY OF THE BACHELOR ARCHIVES COURTESY OF THE BACHELOR ARCHIVES Trace Bulger ’19 passed away Wednesday, October 23 after a long battle with a rare Thaddeus Seymour H’78 passed away Saturday, October 26. Seymour served as the degenerative neuromuscular disease, which he battled while he was a student at 11th President of Wabash College from 1969 until 1978. Wabash. Wallies Prepare to ‘Bleed for the Bell’ ALEXANDRU ROTARU ’22 | between life and death. “We could very ASSISTANT COPY EDITOR • “Anything easily be saving somebody’s life just by against DePauw unites Wabash,” putting on this event and organizing Daren Glore ‘22 said. And this is something where people can donate true for athletics, academics, and blood,” Rotterman said. And “healthy philanthropy. This upcoming week, donors is the easiest way to get [the which is Wellness Week for the blood],” Glore said. Athletic Department, the Student Despite the humanitarian nature of Athletic Advisory Committee (SAAC) the event and the fierce competition and the Sphinx Club are hosting the between Wabash and DePauw, the ‘Bleed for the Bell’ annual blood drive, greatest challenge for this event is on November 5, where Wabash College having people donate blood. On the one and DePauw University are competing hand, “a lot of students are athletes, to see who can give the most amount and you don’t really want to give blood of blood to The American Red Cross. and then go to practice two hours Glore and Connor Rotterman ‘21 are later,” Rotterman said. -

Below Is a Sampling of the Nearly 500 Colleges, Universities, and Service Academies to Which Our Students Have Been Accepted Over the Past Four Years

Below is a sampling of the nearly 500 colleges, universities, and service academies to which our students have been accepted over the past four years. Allegheny College Connecticut College King’s College London American University Cornell University Lafayette College American University of Paris Dartmouth College Lehigh University Amherst College Davidson College Loyola Marymount University Arizona State University Denison University Loyola University Maryland Auburn University DePaul University Macalester College Babson College Dickinson College Marist College Bard College Drew University Marquette University Barnard College Drexel University Maryland Institute College of Art Bates College Duke University McDaniel College Baylor University Eckerd College McGill University Bentley University Elon University Miami University, Oxford Binghamton University Emerson College Michigan State University Boston College Emory University Middlebury College Boston University Fairfield University Morehouse College Bowdoin College Florida State University Mount Holyoke College Brandeis University Fordham University Mount St. Mary’s University Brown University Franklin & Marshall College Muhlenberg College Bucknell University Furman University New School, The California Institute of Technology George Mason University New York University California Polytechnic State University George Washington University North Carolina State University Carleton College Georgetown University Northeastern University Carnegie Mellon University Georgia Institute of Technology -

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 59 In Memory of Christina Elliott Sorum 1944-2005 Copyright © 2005 American Council of Learned Societies Contents Introduction iii Pauline Yu Prologue 1 The Liberal Arts College: Identity, Variety, Destiny Francis Oakley I. The Past 15 The Liberal Arts Mission in Historical Context 15 Balancing Hopes and Limits in the Liberal Arts College 16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz The Problem of Mission: A Brief Survey of the Changing 26 Mission of the Liberal Arts Christina Elliott Sorum Response 40 Stephen Fix II. The Present 47 Economic Pressures 49 The Economic Challenges of Liberal Arts Colleges 50 Lucie Lapovsky Discounts and Spending at the Leading Liberal Arts Colleges 70 Roger T. Kaufman Response 80 Michael S. McPherson Teaching, Research, and Professional Life 87 Scholars and Teachers Revisited: In Continued Defense 88 of College Faculty Who Publish Robert A. McCaughey Beyond the Circle: Challenges and Opportunities 98 for the Contemporary Liberal Arts Teacher-Scholar Kimberly Benston Response 113 Kenneth P. Ruscio iii Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education II. The Present (cont'd) Educational Goals and Student Achievement 121 Built To Engage: Liberal Arts Colleges and 122 Effective Educational Practice George D. Kuh Selective and Non-Selective Alike: An Argument 151 for the Superior Educational Effectiveness of Smaller Liberal Arts Colleges Richard Ekman Response 172 Mitchell J. Chang III. The Future 177 Five Presidents on the Challenges Lying Ahead The Challenges Facing Public Liberal Arts Colleges 178 Mary K. Grant The Importance of Institutional Culture 188 Stephen R. -

2016 NCAC Preseason Men's Soccer Poll

Keri Alexander Luchowski Executive Director P.O. Box 16679 Cleveland, OH 44116 Phone (440) 871-8100 Fax (440) 871-4221 [email protected] www.northcoast.org ALLEGHENY COLLEGE ★ DENISON UNIVERSITY ★ DEPAUW UNIVERSITY ★ HIRAM COLLEGE ★ KENYON COLLEGE OBERLIN COLLEGE ★ OHIO WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY ★ WABASH COLLEGE ★ WITTENBERG UNIVERSITY ★ COLLEGE OF WOOSTER NCAC Men's Soccer Special For Immediate Release KENYON TOPS PRESEASON POLL AS NORTH COAST August 24, 2016 PREPARES FOR 33RD MEN'S SOCCER CAMPAIGN CLEVELAND -- Kenyon has been selected as the preseason favorite based on balloting from league coaches heading into the 33rd North Coast men’s soccer season. The Lords, who posted a 19-2-1 record and advanced to the NCAA Tournament quarterfinals in 2015, earned eight of the first-place votes cast by league coaches to finish atop the poll with 98 total points. Ohio Wesleyan, coming off its NCAA- record 38th Division III NCAA Tournament appearance, earned one first-place vote and finished second in the poll with 89 points, while DePauw rounded out the top-three in third with 78 points and the final first-place vote. Oberlin checked in at fourth with 66 points, while Denison cracked the top-five in fifth with 61 points after posting its second 11-win season in the last three years last fall. Wabash earned the sixth position with 50 points, followed by Allegheny (35), Hiram (29), Wooster (26) and Wittenberg (18). Kenyon enters the 2016 season under the direction of head coach Chris Brown for the 12th consecutive season. In 11 seasons at the helm, Brown has compiled the most wins in program history with a record of 130-58-26, which includes 122 victories over the past nine seasons and four NCAA appearances during that time. -

Depauw University Catalog 2007-08

DePauw University Catalog 2007-08 Preamble .................................................. 2 Section I: The University................................. 3 Section II: Graduation Requirements .................. 8 Section III: Majors and Minors..........................13 College of Liberal Arts......................16 School of Music............................. 132 Section IV: Academic Policies........................ 144 Section V: The DePauw Experience ................. 153 Section VI: Campus Living ............................ 170 Section VII: Admissions, Expenses, Aid ............. 178 Section VIII: Personnel ................................ 190 This is a PDF copy of the official DePauw University Catalog, 2007-08, which is available at http://www.depauw.edu/catalog . This reproduction was created on December 17, 2007. Contact the DePauw University registrar, Dr. Ken Kirkpatrick, with any questions about this catalog: Dr. Ken Kirkpatrick Registrar DePauw University 313 S. Locust St. Greencastle, IN 46135 [email protected] 765-658-4141 Preamble to the Catalog Accuracy of Catalog Information Every effort has been made to ensure that information in this catalog is accurate at the time of publication. However, this catalog should not be construed as a contract between the University and any person. The policies contained herein are subject to change following established University procedures. They may be applied to students currently enrolled as long as students have access to notice of changes and, in matters affecting graduation, have time to comply with the changes. Student expenses, such as tuition and room and board, are determined each year in January. Failure to read this bulletin does not excuse students from the requirements and regulations herein. Affirmative Action, Civil Rights and Equal Employment Opportunity Policies DePauw University, in affirmation of its commitment to excellence, endeavors to provide equal opportunity for all individuals in its hiring, promotion, compensation and admission procedures. -

Class of 2018 Successes

High School Success 2017-18 A U S T I N W A L D O R F S C H O O L C L A S S O F 2 0 1 8 C O L L E G E S O F A C C E P T A N C E A N D M A T R I C U L A T I O N Agnes Scott College Eckerd College Oklahoma State University University of Arizona American University Fordham University Okl ahoma University University of Denver Austin Community College Goucher College Rider University University of Georgia Barnard College Hendrix College Sarah Lawrence College University of North Texas Bates College High Point University Seattle University University of Portland Baylor University Hobart & William Smith College Smith College University of Redlands Centre College Illinois Wesleyan University Southwestern University University of San Fransisco Colorado State University Kansas State University St. Edward's University University of Texas at Austin Connecticut College Lewis and Clark College Stephen F. Austin University University of Texas at Dallas Denison University Loyola University Chicago Texas A&M University University of Texas at San Antonio Depaul University Marymount Manhattan College Texas State University University of Wyoming Drew University Middlebury College Texas Tech University Washington University in St. Louis Drexel University Mount Holyoke College Trinity University Wesleyan College Earlham College Nova Southeastern Univeristy University of Alabama Whitman College Whittier College The Class of 2018 In tota l , e l e v e n g raduates All 1 6 graduates of the class of 2018 applied of the Class of 2018 earned to 7 4 , were accepted to 5 7 , and will $ 2 . -

Kenyon College

Kenyon College Years of Service Recognition Program Tuesday, June 15, 2021 Eleven O’clock in the Morning Table of Contents Five Years 1 Ten Years 19 Fifteen Years 28 Twenty Years 37 Twenty-Five Years 43 Thirty Years 46 Thirty-Five Years 48 Forty Years 51 Distinguished Service Awards 53 Five Years MacKenzie F. Avis Senior Assistant Director of Admissions A proud Michigan native, Mackie Avis made his way to Kenyon to ma- jor in history, study Latin and Czech, and spend a semester abroad in Prague. A true scholar-athlete, he was distinguished on the playing field as a member of the men’s lacrosse team, serving as the team’s captain and lead goal scorer. Mackie and his positive experience at the College inspired his younger brother to join him in Gambier. While staff members in the Enrollment Division are always happy to enroll students whose connection to Kenyon is strengthened by a legacy, we were particularly glad to have more members of the Avis family on campus. Over time, Mackie’s incred- ible devotion to family has inspired us, developing in all a particular care for his clan and for our own. As a son, sibling, cousin, and friend, Mackie is loyal, steady, and fun. Of course, all of these traits have served him well in his work on behalf of the College and the students he inspires every day. Reliable Mackie can be counted on to bring diplomacy and a deft touch to his work as an athletics liaison, completing many hundreds of pre-reads each year.