Don't BASH Your Head In: Rx for Shell Variables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At—At, Batch—Execute Commands at a Later Time

at—at, batch—execute commands at a later time at [–csm] [–f script] [–qqueue] time [date] [+ increment] at –l [ job...] at –r job... batch at and batch read commands from standard input to be executed at a later time. at allows you to specify when the commands should be executed, while jobs queued with batch will execute when system load level permits. Executes commands read from stdin or a file at some later time. Unless redirected, the output is mailed to the user. Example A.1 1 at 6:30am Dec 12 < program 2 at noon tomorrow < program 3 at 1945 pm August 9 < program 4 at now + 3 hours < program 5 at 8:30am Jan 4 < program 6 at -r 83883555320.a EXPLANATION 1. At 6:30 in the morning on December 12th, start the job. 2. At noon tomorrow start the job. 3. At 7:45 in the evening on August 9th, start the job. 4. In three hours start the job. 5. At 8:30 in the morning of January 4th, start the job. 6. Removes previously scheduled job 83883555320.a. awk—pattern scanning and processing language awk [ –fprogram–file ] [ –Fc ] [ prog ] [ parameters ] [ filename...] awk scans each input filename for lines that match any of a set of patterns specified in prog. Example A.2 1 awk '{print $1, $2}' file 2 awk '/John/{print $3, $4}' file 3 awk -F: '{print $3}' /etc/passwd 4 date | awk '{print $6}' EXPLANATION 1. Prints the first two fields of file where fields are separated by whitespace. 2. Prints fields 3 and 4 if the pattern John is found. -

Application for a Certificate of Eligibility to Employ Child Performers

Division of Labor Standards Permit and Certificate Unit Harriman State Office Campus Building 12, Room 185B Albany, NY 12240 www.labor.ny.gov Application for a Certificate of Eligibility to Employ Child Performers A. Submission Instructions A Certificate of Eligibility to Employ Child Performers must be obtained prior to employing any child performer. Certificates are renew able every three (3) years. To obtain or renew a certificate: • Complete Parts B, C, D and E of this application. • Attach proof of New York State Workers’ Compensation and Disability Insurance. o If you currently have employees in New York, you must provide proof of coverage for those New York State w orkers by attaching copies of Form C-105.2 and DB-120.1, obtainable from your insurance carrier. o If you are currently exempt from this requirement, complete Form CE-200 attesting that you are not required to obtain New York State Workers’ Compensation and Disability Insurance Coverage. Information on and copies of this form are available from any district office of the Workers’ Compensation Board or from their w ebsite at w ww.wcb.ny.gov, Click on “WC/DB Exemptions,” then click on “Request for WC/DB Exemptions.” • Attach a check for the correct amount from Section D, made payable to the Commissioner of Labor. • Sign and mail this completed application and all required documents to the address listed above. If you have any questions, call (518) 457-1942, email [email protected] or visit the Department’s w ebsite at w ww.labor.ny.gov B. Type of Request (check one) New Renew al Current certificate number _______________________________________________ Are you seeking this certificate to employ child models? Yes No C. -

Unix Introduction

Unix introduction Mikhail Dozmorov Summer 2018 Mikhail Dozmorov Unix introduction Summer 2018 1 / 37 What is Unix Unix is a family of operating systems and environments that exploits the power of linguistic abstractions to perform tasks Unix is not an acronym; it is a pun on “Multics”. Multics was a large multi-user operating system that was being developed at Bell Labs shortly before Unix was created in the early ’70s. Brian Kernighan is credited with the name. All computational genomics is done in Unix http://www.read.seas.harvard.edu/~kohler/class/aosref/ritchie84evolution.pdfMikhail Dozmorov Unix introduction Summer 2018 2 / 37 History of Unix Initial file system, command interpreter (shell), and process management started by Ken Thompson File system and further development from Dennis Ritchie, as well as Doug McIlroy and Joe Ossanna Vast array of simple, dependable tools that each do one simple task Ken Thompson (sitting) and Dennis Ritchie working together at a PDP-11 Mikhail Dozmorov Unix introduction Summer 2018 3 / 37 Philosophy of Unix Vast array of simple, dependable tools Each do one simple task, and do it really well By combining these tools, one can conduct rather sophisticated analyses The Linux help philosophy: “RTFM” (Read the Fine Manual) Mikhail Dozmorov Unix introduction Summer 2018 4 / 37 Know your Unix Unix users spend a lot of time at the command line In Unix, a word is worth a thousand mouse clicks Mikhail Dozmorov Unix introduction Summer 2018 5 / 37 Unix systems Three common types of laptop/desktop operating systems: Windows, Mac, Linux. Mac and Linux are both Unix-like! What that means for us: Unix-like operating systems are equipped with “shells”" that provide a command line user interface. -

Program #6: Word Count

CSc 227 — Program Design and Development Spring 2014 (McCann) http://www.cs.arizona.edu/classes/cs227/spring14/ Program #6: Word Count Due Date: March 11 th, 2014, at 9:00 p.m. MST Overview: The UNIX operating system (and its variants, of which Linux is one) includes quite a few useful utility programs. One of those is wc, which is short for Word Count. The purpose of wc is to give users an easy way to determine the size of a text file in terms of the number of lines, words, and bytes it contains. (It can do a bit more, but that’s all of the functionality that we are concerned with for this assignment.) Counting lines is done by looking for “end of line” characters (\n (ASCII 10) for UNIX text files, or the pair \r\n (ASCII 13 and 10) for Windows/DOS text files). Counting words is also straight–forward: Any sequence of characters not interrupted by “whitespace” (spaces, tabs, end–of–line characters) is a word. Of course, whitespace characters are characters, and need to be counted as such. A problem with wc is that it generates a very minimal output format. Here’s an example of what wc produces on a Linux system when asked to count the content of a pair of files; we can do better! $ wc prog6a.dat prog6b.dat 2 6 38 prog6a.dat 32 321 1883 prog6b.dat 34 327 1921 total Assignment: Write a Java program (completely documented according to the class documentation guidelines, of course) that counts lines, words, and bytes (characters) of text files. -

Praat Scripting Tutorial

Praat Scripting Tutorial Eleanor Chodroff Newcastle University July 2019 Praat Acoustic analysis program Best known for its ability to: Visualize, label, and segment audio files Perform spectral and temporal analyses Synthesize and manipulate speech Praat Scripting Praat: not only a program, but also a language Why do I want to know Praat the language? AUTOMATE ALL THE THINGS Praat Scripting Why can’t I just modify others’ scripts? Honestly: power, flexibility, control Insert: all the gifs of ‘you can do it’ and ‘you got this’ and thumbs up Praat Scripting Goals ~*~Script first for yourself, then for others~*~ • Write Praat scripts quickly, effectively, and “from scratch” • Learn syntax and structure of the language • Handle various input/output combinations Tutorial Overview 1) Praat: Big Picture 2) Getting started 3) Basic syntax 4) Script types + Practice • Wav files • Measurements • TextGrids • Other? Praat: Big Picture 1) Similar to other languages you may (or may not) have used before • String and numeric variables • For-loops, if else statements, while loops • Regular expression matching • Interpreted language (not compiled) Praat: Big Picture 2) Almost everything is a mouse click! i.e., Praat is a GUI scripting language GUI = Graphical User Interface, i.e., the Objects window If you ever get lost while writing a Praat script, click through the steps using the GUI Getting Started Open a Praat script From the toolbar, select Praat à New Praat script Save immediately! Save frequently! Script Goals and Input/Output • Consider what -

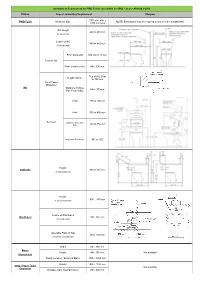

Summary of Requirement for PWD Toilets (Not Within an SOU) – As Per AS1428.1-2009

Summary of Requirement for PWD Toilets (not within an SOU) – as per AS1428.1-2009 Fixture Aspect and/or Key Requirement Diagram 1900 mm wide x PWD Toilet Minimum Size NOTE: Extra space may be required to allow for the a washbasin. 2300 mm long WC Height 460 to 480 mm (to top of seat) Centre of WC 450 to 460 mm (from side wall) From back wall 800 mm ± 10 mm Front of WC From cistern or like Min. 600 mm Top of WC Seat Height of Zone to 700 mm Toilet Paper Dispenser WC Distance of Zone Max. 300mm from Front of QC Height 150 to 200 mm Width 350 to 400 mm Backrest Distance above WC Seat 120 to 150 mm Angle from Seat Hinge 90° to 100° Height Grabrails 800 to 810 mm (to top of grab rail) Height 800 – 830 mm (to top of washbasin) Centre of Washbasin Washbasin Min. 425 mm (from side wall) Operable Parts of Tap Max. 300 mm (from front of washbasin) Width Min. 350 mm Mirror Height Min. 950 mm Not available (if provided) Fixing Location / Extent of Mirror 900 – 1850 mm Height 900 – 1100 mm Soap / Paper Towel Not available Dispenser Distance from Internal Corner Min. 500 mm Summary of Requirement for PWD Toilets (not within an SOU) – as per AS1428.1-2009 Fixture Aspect and/or Key Requirement Diagram Height 1200 – 1350 mm PWD Clothes Hook Not available Distance from Internal Corner Min. 500 mm Height 800 – 830 mm As vanity bench top Width Min. 120 mm Depth 300 – 400 mm Shelves Not available Height 900 – 1000 mm As separate fixture (if within any required Width 120 – 150 mm circulation space) Length 300 – 400 mm Width Min. -

Deviceinstaller User Guide

Device Installer User Guide Part Number 900-325 Revision C 03/18 Table of Contents 1. Overview ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Devices ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Choose the Network Adapter for Communication ....................................................................... 2 Search for All Devices on the Network ........................................................................................ 2 Change Views .............................................................................................................................. 2 Add a Device to the List ............................................................................................................... 3 View Device Details ..................................................................................................................... 3 Device Lists ................................................................................................................................. 3 Save the Device List ................................................................................................................ 3 Open the Device List ............................................................................................................... 4 Print the Device List ................................................................................................................ -

Sys, Shutil, and OS Modules

This video will introduce the sys, shutil, glob, and os modules. 1 The sys module contains a few tools that are often useful and will be used in this course. The first tool is the argv function which allows the script to request a parameter when the script is run. We will use this function in a few weeks when importing scripts into ArcGIS. If a zero is specified for the argv function, then it will return the location of the script on the computer. This can be helpful if the script needs to look for a supplemental file, such as a template, that is located in the same folder as the script. The exit function stops the script when it reach the exit statement. The function can be used to stop a script when a certain condition occurs – such as when a user specifies an invalid parameter. This allows the script to stop gracefully rather than crashing. The exit function is also useful when troubleshooting a script. 2 The shutil module contains tools for moving and deleting files. The copy tool makes a copy of a file in a new location. The copytree tool makes a copy of an entire folder in a new location. The rmtree tool deletes an entire folder. Note that this tool will not send items to the recycling bin and it will not ask for confirmation. The tool will fail if it encounters any file locks in the folder. 3 The os module contains operating system functions – many of which are often useful in a script. -

Useful Commands in Linux and Other Tools for Quality Control

Useful commands in Linux and other tools for quality control Ignacio Aguilar INIA Uruguay 05-2018 Unix Basic Commands pwd show working directory ls list files in working directory ll as before but with more information mkdir d make a directory d cd d change to directory d Copy and moving commands To copy file cp /home/user/is . To copy file directory cp –r /home/folder . to move file aa into bb in folder test mv aa ./test/bb To delete rm yy delete the file yy rm –r xx delete the folder xx Redirections & pipe Redirection useful to read/write from file !! aa < bb program aa reads from file bb blupf90 < in aa > bb program aa write in file bb blupf90 < in > log Redirections & pipe “|” similar to redirection but instead to write to a file, passes content as input to other command tee copy standard input to standard output and save in a file echo copy stream to standard output Example: program blupf90 reads name of parameter file and writes output in terminal and in file log echo par.b90 | blupf90 | tee blup.log Other popular commands head file print first 10 lines list file page-by-page tail file print last 10 lines less file list file line-by-line or page-by-page wc –l file count lines grep text file find lines that contains text cat file1 fiel2 concatenate files sort sort file cut cuts specific columns join join lines of two files on specific columns paste paste lines of two file expand replace TAB with spaces uniq retain unique lines on a sorted file head / tail $ head pedigree.txt 1 0 0 2 0 0 3 0 0 4 0 0 5 0 0 6 0 0 7 0 0 8 0 0 9 0 0 10 -

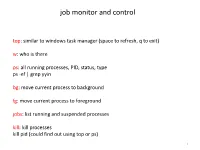

Install and Run External Command Line Softwares

job monitor and control top: similar to windows task manager (space to refresh, q to exit) w: who is there ps: all running processes, PID, status, type ps -ef | grep yyin bg: move current process to background fg: move current process to foreground jobs: list running and suspended processes kill: kill processes kill pid (could find out using top or ps) 1 sort, cut, uniq, join, paste, sed, grep, awk, wc, diff, comm, cat All types of bioinformatics sequence analyses are essentially text processing. Unix Shell has the above commands that are very useful for processing texts and also allows the output from one command to be passed to another command as input using pipe (“|”). less cosmicRaw.txt | cut -f2,3,4,5,8,13 | awk '$5==22' | cut -f1 | sort -u | wc This makes the processing of files using Shell very convenient and very powerful: you do not need to write output to intermediate files or load all data into the memory. For example, combining different Unix commands for text processing is like passing an item through a manufacturing pipeline when you only care about the final product 2 Hands on example 1: cosmic mutation data - Go to UCSC genome browser website: http://genome.ucsc.edu/ - On the left, find the Downloads link - Click on Human - Click on Annotation database - Ctrl+f and then search “cosmic” - On “cosmic.txt.gz” right-click -> copy link address - Go to the terminal and wget the above link (middle click or Shift+Insert to paste what you copied) - Similarly, download the “cosmicRaw.txt.gz” file - Under your home, create a folder -

ANSWERS ΤΟ EVEN-Numbered

8 Answers to Even-numbered Exercises 2.1. WhatExplain the following unexpected are result: two ways you can execute a shell script when you do not have execute permission for the file containing the script? Can you execute a shell script if you do not have read permission for the file containing the script? You can give the name of the file containing the script as an argument to the shell (for example, bash scriptfile or tcsh scriptfile, where scriptfile is the name of the file containing the script). Under bash you can give the following command: $ . scriptfile Under both bash and tcsh you can use this command: $ source scriptfile Because the shell must read the commands from the file containing a shell script before it can execute the commands, you must have read permission for the file to execute a shell script. 4.3. AssumeWhat is the purpose ble? you have made the following assignment: $ person=zach Give the output of each of the following commands. a. echo $person zach b. echo '$person' $person c. echo "$person" zach 1 2 6.5. Assumengs. the /home/zach/grants/biblios and /home/zach/biblios directories exist. Specify Zach’s working directory after he executes each sequence of commands. Explain what happens in each case. a. $ pwd /home/zach/grants $ CDPATH=$(pwd) $ cd $ cd biblios After executing the preceding commands, Zach’s working directory is /home/zach/grants/biblios. When CDPATH is set and the working directory is not specified in CDPATH, cd searches the working directory only after it searches the directories specified by CDPATH. -

Linux Networking Cookbook.Pdf

Linux Networking Cookbook ™ Carla Schroder Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Paris • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo Linux Networking Cookbook™ by Carla Schroder Copyright © 2008 O’Reilly Media, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (safari.oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: (800) 998-9938 or [email protected]. Editor: Mike Loukides Indexer: John Bickelhaupt Production Editor: Sumita Mukherji Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery Copyeditor: Derek Di Matteo Interior Designer: David Futato Proofreader: Sumita Mukherji Illustrator: Jessamyn Read Printing History: November 2007: First Edition. Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O’Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. The Cookbook series designations, Linux Networking Cookbook, the image of a female blacksmith, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Java™ is a trademark of Sun Microsystems, Inc. .NET is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O’Reilly Media, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein.