Indentured Indians in Natal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dominant Anopheles Vectors of Human Malaria in the Asia-Pacific

Sinka et al. Parasites & Vectors 2011, 4:89 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/4/1/89 RESEARCH Open Access The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in the Asia-Pacific region: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis Marianne E Sinka1*, Michael J Bangs2, Sylvie Manguin3, Theeraphap Chareonviriyaphap4, Anand P Patil1, William H Temperley1, Peter W Gething1, Iqbal RF Elyazar5, Caroline W Kabaria6, Ralph E Harbach7 and Simon I Hay1,6* Abstract Background: The final article in a series of three publications examining the global distribution of 41 dominant vector species (DVS) of malaria is presented here. The first publication examined the DVS from the Americas, with the second covering those species present in Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Here we discuss the 19 DVS of the Asian-Pacific region. This region experiences a high diversity of vector species, many occurring sympatrically, which, combined with the occurrence of a high number of species complexes and suspected species complexes, and behavioural plasticity of many of these major vectors, adds a level of entomological complexity not comparable elsewhere globally. To try and untangle the intricacy of the vectors of this region and to increase the effectiveness of vector control interventions, an understanding of the contemporary distribution of each species, combined with a synthesis of the current knowledge of their behaviour and ecology is needed. Results: Expert opinion (EO) range maps, created with the most up-to-date expert knowledge of each DVS distribution, were combined with a contemporary database of occurrence data and a suite of open access, environmental and climatic variables. -

Tla Hearing Board

TLA HEARING BOARD Hearing Schedule from 01/10/2018 to 01/10/2018 Location: AHMEDABAD S.No. TM Class Hearing Hearing Proprietor Agent Name Despatch Despatch No. Date Schedule Name No. Date 1 2876867 19 01/10/2018 Morning MORBI CERAMIC T.C.PATEL & CO., ---- 07/08/2018 PVT.LTD. 16:23:14 (10.30 am to 1.00 pm) 2 2966977 5 01/10/2018 Morning TREXGEN T.C.PATEL & CO., ---- 07/08/2018 PHARMACEUTICALS 16:23:14 (10.30 am PVT. LTD to 1.00 pm) 3 3077180 30 01/10/2018 Morning MUSARRATALI T.C.PATEL & CO., ---- 07/08/2018 MAQBULAHMED 16:23:16 (10.30 am ANSARI to 1.00 pm) 4 3080279 31 01/10/2018 Morning PATEL T.C.PATEL & CO., ---- 07/08/2018 SANJAYKUMAR 16:23:20 (10.30 am MAHENDRABHAI to 1.00 (HUF) pm) 5 3084456 19 01/10/2018 Morning HARMONY MR. RAJENDRA ---- 07/08/2018 SURFACES LIMITED RAJNIKANT RAVAL 12:24:47 (10.30 am PROPRIETOR OF to 1.00 TRADESAFE pm) 6 3125619 14 01/10/2018 Morning MAVJIBHAI O. T.C.PATEL & CO., ---- 07/08/2018 SHIRVI 16:16:18 (10.30 am to 1.00 pm) 7 3125620 19 01/10/2018 Morning MAVJIBHAI O. T.C.PATEL & CO., ---- 07/08/2018 SHIRVI 16:16:18 (10.30 am to 1.00 pm) 8 3080274 25 01/10/2018 Morning MAHENDRAKUMAR T.C.PATEL & CO., ---- 07/08/2018 MOTILAL KOTHARI 16:23:18 (10.30 am to 1.00 pm) 9 3107468 24 01/10/2018 Morning MAITREYA MAITREYA ---- 07/08/2018 PANKAJBAHI PANKAJBAHI 11:21:39 (10.30 am MEHTA MEHTA to 1.00 pm) 10 3100884 5 01/10/2018 Morning TROIKAA TROIKAA ---- 07/08/2018 PHARMACEUTICALS PHARMACEUTICALS 11:21:45 (10.30 am LTD LTD to 1.00 pm) 11 3107800 30 01/10/2018 Morning ATA FOODS PVT. -

Extracts of Annual Return 2019

First Name Middle Name Last Name Folio Number DP ID-Client Id Account Number Number of Shares held Class of Shares First Name Middle Name Last Name Folio Number DP ID-Client Id Accoount Number Number of shares held Class of shares A A PALANIAPPAN IN30154914500110 3000 Equity Shares A ABDULMUTHALEEF IN30039418411288 500 Equity Shares A ABDULVAHEETH 1203320009143157 100 Equity Shares A AKILA IN30177413526661 645 Equity Shares A ANBANANTHAN A005295 2100 Equity Shares A ARUNA KUMARI IN30154954641721 250 Equity Shares A ARUNMANI 1208160001178720 350 Equity Shares A ASHOK KUMAR 1203230002287272 998 Equity Shares A ATHIYAN IN30163741910124 200 Equity Shares A BABU 1204010000058132 500 Equity Shares A BALA GANESAN IN30108022126704 710 Equity Shares A BENNETT IN30023911722735 700 Equity Shares A BHAGAVATHIAMMAL 1601430105165465 500 Equity Shares A C MAVANI HUF IN30048429312899 2000 Equity Shares A C THARKAR 1301740000013364 200 Equity Shares A C V SEKHARA RAO IN30267933159089 2 Equity Shares A C VARGHESE IN30151610218693 100 Equity Shares A C VIGNESH IN30039419519831 200 Equity Shares A C VISWANATHAN IN30088813141151 3630 Equity Shares A Carrolene Vincia IN30281410739842 150 Equity Shares A Chanchal Surana 1207650000001416 4050 Equity Shares A DEEPA N KAMATH IN30113526276499 50 Equity Shares A DEEPA RANI IN30051320083659 410 Equity Shares A DEVENDRAN IN30163740588097 10 Equity Shares A DINESHKUMAR A DINESHKUMAR 1208160000802961 25 Equity Shares A EASWARAN IN30051311035375 100 Equity Shares A G SHARES AND SEC LTD IN30100610091238 290 Equity Shares -

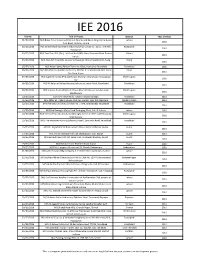

IEE 2016 File No

IEE 2016 File No. Title of Project District Year of Filing 01/IEE/2016 M/S Breez Frost Industries (Pvt) Ltd, (Stones and Beads Mfg,Co) Harbanse Lahore 2016 Pura Road, TajPura, Lahore 02/IEE/2016 M/s One the Mall (Commercial Building) Plot Survey No. 167/1, The Mall, Rawalpindi 2016 Rawalpindi 03/IEE/2016 M/S Zam Zam LPG, (Pvt), Ltd Chak No 3/WB, 6 km. Burewala Road District Vehari 2016 Vehari. 04/IEE/2016 M/S Abdullah Rice Mills. Mouza Kot Saisingh Chiniot road District Jhang. Jhang 2016 05/IEE/2016 M/S Amcon (pvt), Paradis Tower at,136/c, D-ground, Faisalabad Faisalabad 2016 06/IEE/2016 M/S Medifarnecs (Harble medicene), Plot No. 9-D, Small Ind Estate. Feroz Kasur 2016 Pur Road, Kasur 07/IEE/2016 M/S Suprewe Farnes,(Pvt) Ltd Mouza Dholwan, Manawala, Farooqabad, Sheikhupura 2016 SKP 08/IEE/2016 M/S Al-Raheem Vallays Housing Scheme at Satian Road, Faisalabad Faisalabad 2016 09/IEE/2016 M/S Seasons Foods (Pvt) Ltd, Mouza Mian Ali Fakiran, Safadar abad. Sheikhupura 2016 Sheikhupura 10/IEE/2016 M/S A.N Textile Mills , Satiana road Faisalabad Faisalabad 2016 11/IEE/2016 M/S Akbar oil Traders Mouza Chak No.175/RB, Shak Kot, Nankana Nankana Sahib 2016 12/IEE/2016 M/S Mianwali LPG (Pvt) Ltd Chak No. 77/RB, Jarawnwala, Faisalabad Faisalabad 2016 13/IEE/2016 M/S Pak Packages (Ext), (Food Packaging Files), 9-S.I.E, Lahore Lahore 2016 14/IEE/2016 M/S Friends Petro Chamicals Ltd (Storage) 2.2-km off SKP road Ferozwala, Sheikhupura 2016 Sheikhupura. -

Punjab Part Iv

Census of India, 1931 VOLUME ,XVII PUNJAB PART IV. ADMINISTRATIVE VOLlJME BY KHA~ AHMAD HASAN KHAN, M.A., K.S., SUPERINTENDENT OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB & DELHI. Lahore FmN'l'ED AT THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING PRESS, PUNJAB. 1933 Revised L.ist of Agents for the Sale of Punja b Government Pu hlications. ON THE CONTINENT AND UNITED KINGDOM. Publications obtainable either direct from the High Oommissioner for India. at India House, Aldwych. London. W. O. 2. or through any book seller :- IN INDIA. The GENERAL MANAGER, "The Qaumi Daler" and the Union Press, Amritsar. Messrs. D. B.. TARAPOREWALA. SONS & Co., Bombay. Messrs. W. NEWMAN & 00., Limite:>d, Calolltta. Messrs. THAOKER SPINK & Co., Calcutta. Messrs. RAMA KaIsHN A. & SONS, Lahore The SEORETARY, Punjab Religiolls Book Sooiety, Lahore. The University Book Agency, Kaoheri Road, Labore. L. RAM LAL SURI, Proprietor, " The Students' Own Agency," Lahore. L. DEWAN CHAND, Proprietor, The Mercantile Press, Lahore. The MANAGER, Mufid-i-'Am Press. Lahore. The PROPRIETOR, Punjab Law BOQk Mart, Lahore. Thp MANAGING PROPRIETOR. The Commercial Book Company, Lahore. Messrs. GOPAL SINGH SUB! & Co., Law Booksellers and Binders, Lahore. R. S. JAln\.A. Esq., B.A., B.T., The Students' Popular Dep6t, Anarkali, Lahore. Messrs. R. CAl\IBRAY & Co •• 1l.A., Halder La.ne, BowbazlU' P.O., Calcutta. Messrs. B. PARIKH & Co. Booksellers and Publishers, Narsinhgi Pole. Baroda. • Messrs. DES BROTHERS, Bo(.ksellers and Pnblishers, Anarkali, Lahore. The MAN AGER. The Firoz Book Dep6t, opposite Tonga Stand of Lohari Gate, La.hore. The MANAGER, The English Book Dep6t. Taj Road, Agra. ·The MANAGING PARTNER, The Bombay Book Depbt, Booksellers and Publishers, Girgaon, Bombay. -

University of Nairobi Students' Association Independent Electoral

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI STUDENTS’ ASSOCIATION INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL COMMISION COLLEGE OF BIOLOGICAL AND PHYSICAL SCIENCES ELECTORAL COLLEGE SCHOOOL OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATICS PHD IN INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND PHD IN COMPUTER SCIENCE S/No. Student Names Reg. No. Citizenship Disability status Year of study 1 WANGUNYU PAULINE WAMBUI P80/52756/2018 Kenyan None 3 2 MUTURI MOSES KURIA P80/52781/2018 Kenyan None 3 3 KAMUNYA SAMUEL MUTHEE P80/53896/2018 Kenyan None 3 4 OSERO BENARD ONG'ERA P80/51504/2017 Kenyan None 3 5 ABUODHA ATIENO LUCY P80/51585/2017 Kenyan None 3 6 WANJAWA BARACK WAMKAYA P80/51662/2017 Kenyan None 3 7 AKUKU BONIFACE OKELO P80/51686/2017 Kenyan None 3 8 OTIENO ERICK OCHIENG P80/51691/2017 Kenyan None 3 9 MULI ELIZABETH MWIKALI P80/51786/2017 Kenyan None 3 10 MULUNDA CHRISTINE KAGONYA P80/52206/2017 Kenyan None 3 11 OKOLA ISAAC P80/52197/2017 Kenyan None 3 12 OMINA JAMES ADUNYA P80/49903/2015 Kenyan None 3 13 NGARUIYA MARY NJERI P80/50002/2015 Kenyan None 3 14 LWANDE CHARLES OMONDI P80/98407/2015 Kenyan None 3 15 MUTURI PETER NDWIGA P80/99008/2015 Kenyan None 3 16 KIBUKU RACHAEL NJERI P80/99449/2015 Kenyan None 3 17 KAMAU SHARON WANJIRU P80/94228/2014 Kenyan None 3 18 OKIOGA EDGAR NYAMWEYA P80/91081/2013 Kenyan None 3 19 OKIRO JOSEPH ONYANGO P80/92601/2013 Kenyan None 3 20 KITUKU BENSON NZIOKA P80/92741/2013 Kenyan None 3 21 KENEI JONAH KIPCHIRCHIR P80/92801/2013 Kenyan None 3 22 KAMAU JOSEPH KURIA P80/92821/2013 Kenyan None 3 23 OMBUI EDWARD OSORO P80/92844/2013 Kenyan None 3 24 MUNENE JAMES KINYUA P80/92901/2013 Kenyan None -

Remembering Ghazi Ilam Din Shaheed

Südasien-Chronik - South Asia Chronicle 7/2017, S. 201-225 © Südasien-Seminar der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin ISBN: 978-3-86004-330-1 Remembering Ghazi Ilam Din Shaheed: The Construction of Memory, Religious Affect and Blasphemy in the Muslim Public Sphere in Colonial Panjab and Contemporary Pakistan HASHIM RASHID [email protected]/[email protected] KEYWORDS: GHAZI SHAHEED, PUNJAB, PAKISTAN, PUBLIC SPHERE, RELIGION 201 "This young son of a carpenter has surpassed us, O educated ones" – Sir Allama Mohammad Iqbal "We have already expressed our regrets on the murder of Rajpal…the reasons for regret in the current situation were two: one, that an individual was killed against the constitution, and, two, that the atmosphere had, to a great extent, been temperate and this event has allowed selfishly motivated groups to spread chaos." – Inqilaab, 12 April 1929, 'Rajpal’s Murder: Attempts to Spoil the Atmosphere'. The specter of Ghazi Ilam Din Shaheed continues to haunt Pakistan. The convicted murderer of a Hindu publisher in Lahore in 1929 contin- ues to be remembered as the role model for how a Muslim should respond to blasphemy against the Prophet Mohammad. When the Aasia Bibi case erupted in November 2010, pamphlets and sermons on who he was and the need for someone to take on his legacy was articulated across clerical circles. The entire affair ended with the ghost of Ilam Din possessing another individual: Mumtaz Qadri. The young FORUM boy who murdered a Hindu publisher, Raj Pal, guilty of circulating the blasphemous book, Rangeela Rasul on 2 April 1929, near Taxali Gate in Lahore is remembered as a hero. -

Dynamics of Social Exclusion Thesis

BHADOHI CARPET INDUSTRY: DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL EXCLUSION THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN SOCIOLOGY BY ASFIYA KARIMI UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ABDUL MATIN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2016 The work is dedicated to my Loving MOM and DAD who always encourage me to follow my dreams Acknowledgement It’s been a long road, of journey there are so many people to whom thanks I extend. First and foremost is a well-deserved thanks to my supervisor Prof. Abdul Matin Chairperson of the department of Sociology. He not only like a mentor but as a critic has crystallized me. He had involved me in several activities that helped me in shaping my personality. I can never forget his care and affection. I had been in a real pinch! Great mentorship, so approachable, good advice is his game. His debt on me will never be paid. I am extremely grateful to the UGC, for granting me the fellowship that really helped me to devote my energies fully into research work. It is a pleasure to express my gratitude wholeheartedly to the Library of Indian Institute of Economic Growth and Ratan Tata Library in Delhi University and Central library of BHU and JNU for allowing me to access their resources. I wish to thanks the staff of Maulana Azad Library of AMU for their cooperative assistance during my studies. I would also like to thank Ibne Hasan our seminar librarian of Sociology for providing the required material and also the seminar library of Commerce, History and Economics department of AMU for providing me the required material during my research work. -

Dengue Plan 2017

Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Responsibility of LWMC .......................................................................................................................... 4 1. Objectives:- ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Duration of the Plan:- ............................................................................................................................ 5 3. Scope of Work ...................................................................................................................................... 5 4. LWMC Anti Dengue Activities .......................................................................................................... 10 5.1 Plot Clearance ............................................................................................................................. 10 5.1.1 Open Plots Detail ................................................................................................................ 10 5.1.2 Schedule for Open Plot Clearance ...................................................................................... 11 5.1.3 Targets for Removal of Waste from Open Plots ................................................................. 13 5.1.4 SOPs for Plot Clearance ..................................................................................................... -

Consolidated Statement Showing Scheduled Castes, Scheduled

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME I INDIA PART V-B (iii) Consolidated Statement Showing Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Denotified Communities and other Communities of Similar Status III Different Statute ~Censllses Starting from 1921 ~---""" ~ \\EE!f1.i1At: 7i1?;" ~ .. ;,-,..- - -.., .... ', '" , ~ r "","II' " t:( ., 'DR~ r " Y;;. t -;.. \. ~-," 0 .. ", ~ ) ~ '" .".._\... ./,~ '''':' ......", '-. -.-- _-"EY '* 'Vi.w D-'--~\· - , A. MITRA of the Indian Civil Service Registrar General and ex-officio Census Commissioner for JnQia CENSUS OF INDIA 1961-UNION PUBLICATIONS .. General Report on the Census: PART I-A General Report PART I-A (i) (Text) Levels of Regional Development in India PART I-A (ii) (Tables) Levels of Regional Development in India PART I-B Vital Statistics of the decade PART I-C Subsidiary Tables -EART II .. .. Cemu" Tables on Population: )PART If-A(i) General Population Tables PART lI-A(ii) Union Primary CenslIs Abstracts PART IT-D(i) General Economic Tables ( B-1 to B-IV) PART IT-B(ii) General Economic Tables (B-V) PART If-f3(iii) General Economic Tables (B-VI to B-IX) PART JI. -C(i) Social and Cultural Tables PART H-C(ii) Language' Tables PART II-C(iii) Migration Tables ( D-T to D-V) PART II-C(iv) Migration Tables CD-VI) PART III . " HOllsehold Economic Tables: PART rrr (i) lIomehold Economic Tables (14 States) PA RT ITT Oi) Household Economic Tables (India, Uttar Pradesh and Union Territories) PART IV .. .. Report on Housing and Establishments PART IV--A(i) Housing Report PART IV-A(ii) Report on Industrial Establish\!)ents PART IV-A(iii)Housc Types and Village layouts PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V . -

Dr. Jaswant Singh Neki

III/2015 NAGAARA IN DEDICATION Dr. Jaswant Singh Neki The Chardi Kalaa Foundation In the home of the brave and the land of the free, the spirit of the Khalsa shall rise up for all to see http://www.chardikalaa.com/ EEditorialEditorial JASWANT SINGH NEKI A Life to Celebrate uru Granth Sahib repeatedly institution in Chandigarh that imparted make for a fuller, richer and fruitful warns us that whoever and postgraduate specialty training to life. A talented and lucky few are then G whatever is born must die: Indian medical graduates. I have run remembered and celebrated as public “Jo ayaa so challsee sabh koi aayee vaarye” across many who graduated from there intellectuals. (p.473). Furthermore, we have only one – clearly their academic standards This is where I pigeonhole Dr life to live. were frst rate and a compliment to the Jaswant Singh Neki; this is where Dr students and faculty. He also spent An obituary, reckoning of a life, is Neki excelled. And I speak from the some time in France and rounded off not always easy to capture in words vantage point of one who helped edit a distinguished career with a stint with and some lives make it a daunting the translation of his seminal work – the World Health Organisation. Essays undertaking; today is such an occasion. Ardaas in English – and also participated within this Issue will explore his life- Eulogies, for some people like Dr with him at many a symposia on Sikhs journey in more detail. Jaswant Singh Neki, are an almost and Sikhi over the years where we impossible task. -

AUTHOR INDEX (By Abstract Number)

AUTHOR INDEX (By Abstract Number) A Adler, Douglas G. 498, 1189, Alaber, Omar A. Mo1279, Sa1303, Aloreidi, Khalil Su1550 Aadam, A. Aziz 667, 1183, Mo1242, Mo1285, Mo1639, Sa1434 Alotaibi, Nawaf Sa1468 Sa2015, Sp458, Su1298, Su1424 Sa1228, Sa1231, Sa1428, Sa1438, Alajati, bana Tu1024 Alqahtani, Aayed 93, Sp786 Aamar, Ali Su1291, Su1550 Sa1950, Sp1131, Sp589, Su1249, Alameri, Aws Su1450 Al-Qaisi, Mohanad T. Su1031, Abad, Mary Raina Angeli 878, Su1260, Su1291, Su1517, Su1555, alam Janjua, Muhammad Su1548 Sa1251, Sa1262, Sa1268, Sa1283, Su1574, Tu1146, Tu1147, Tu1158 fayyaz Tu1085 Alrajhi, Saad Su1521 Sa1296 Aepli, Patrick 495 Alansari, Ahmed Sa2005 Al-Sabah, Salman Sa1959 Abadia, Carlos D. Su1055 Aerts, Maridi 958, Su1268 Alaoui, Ahmed Amine Mo1624, Al-Shahrani, Abdullah A. Sa1955, Abbas, Aamer Tu1032 Afghani, Elham Sp586 Mo1667 Su1260, Su1514 Abbas, Ali M. 973, Sa1944, Su1269, Agarunov, Emil Sa1410, Su1017, Alateeqi, Fadhel Mo1988 Al-Taee, Ahmad Su1569, Su1570 Su1427, Tu1029, Tu1114 Tu1512 Alazmi, Waleed Sa1959 Altamirano, Maria J. Mo1690 Abdalhadi, Haneen Su1250 Agarwal, Amol 496 Albashir, Siwar M. Tu1153 Altayar, Osama Sa1426, Sa1955 Abdelfatah, Mohamed M. 52, Aggarwal, Manik Tu1560 Albawaliz, Anas Sa1437 Althoff, Friederike C. Su1443 1189, Sa1278, Sa1293, Tu1493, Aggarwal, Soorya N. Sa1465 Albeniz, Eduardo 361, 666, 1179, Aluizio, Carla L. Mo1741 Tu1524 Aghaie Meybodi, Mohamad 51, Mo1749 Alvarado, Marlon Rojas Sa1244 Abdelfattah, Ahmed Sa1243 55, 666 Alberani, Angela Tu1136 Alvarez, Alberto 361 Abdelfattah, Thaer Su1326 Agnihotri, Abhishek Mo1245, Albillos, Agustin Su1286 Alvarez-Gonzalez, Marco A. 1179 Abdelhafez, Mohamed 961, Mo1271, Mo1292, Sa1969, Sa2052, Albrecht, Heinz 495 Alves, Jairo S. Tu1087 Su1337 Su1325, Su1443, Tu1542 Alburquerque, Marco Su1055, Alves, Venancio A. Tu1563 Abdelqader, Abdelhai Sa1467 Agrawal, Anurag Tu1177, Su1279, Su1515 Alvisi, Costanza Su1536 Abdelrahim, Mohamed Mo1697, Tu1178, Tu1179 Aldhwayan, Madhawi Sa1961 Al-Yaman, Wael A.