Daniel Compares Notes with Jeremiah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daniel Abraham David Elijah Esther Hannah John Moses

BIBLE CHARACTER FLASH CARDS Print these cards front and back, so when you cut them out, the description of each person is printed on the back of the card. ABRAHAM DANIEL DAVID ELIJAH ESTHER HANNAH JOHN MOSES NOAH DAVID DANIEL ABRAHAM 1 Samuel 16-30, The book of Daniel Genesis 11-25 2 Samuel 1-24 • Very brave and stood up for His God Believed God’s • A person of prayer (prayed 3 • • A man after God’s heart times/day from his youth) promises • A great leader Called himself what • Had God’s protection • • A protector • Had God’s wisdom (10 times God called him • Worshiper more than anyone) • Rescued his entire • Was a great leader to his nation from evil friends HANNAH ESTHER ELIJAH 1 Samuel 1-2 Book of Esther 1 Kings 17-21, 2 Kings 1-3 • Prayers were answered • God put her before • Heard God’s voice • Kept her promises to kings • Defeated enemies of God • Saved her people God • Had a family who was • Great courage • Miracle worker used powerfully by God NOAH MOSES JOHN Genesis 6-9 Exodus 2-40 Gospels • Had favor with God • Rescued his entire • Knew how much Jesus • Trusted God country loved him. • Obeyed God • God sent him to talk to • Was faithful to Jesus • Wasn’t afraid of what the king when no one else was people thought about • Was a caring leader of • Had very powerful him his people encounters with God • Rescued the world SARAH GIDEON PETER JOSHUA NEHEMIAH MARY PETER GIDEON SARAH Gospels judges 6-7 Gensis 11-25 • Did impossible things • Saved his city • Knew God was faithful with Jesus • Destroyed idols to His promises • Raised dead people to • Defeated the enemy • Believed God even life without fighting when it seemed • God was so close to impossible him, his shadow healed • Faithful to her husband, people Abraham MARY NEHEMIAH JOSHUA Gospels Book Nehemiah Exodus 17-33, Joshua • Brought the future into • Rebuilt the wall for his • Took people out of her day city the wilderness into the • God gave her dreams to • Didn’t listen to the promised land. -

Daniel 1. Who Was Daniel? the Name the Name Daniel Occurs Twice In

Daniel 1. Who was Daniel? The name The name Daniel occurs twice in the Book of Ezekiel. Ezek 14:14 says that even Noah, Daniel, and Job could not save a sinful country, but could only save themselves. Ezek 28:3 asks the king of Tyre, “are you wiser than Daniel?” In both cases, Daniel is regarded as a legendary wise and righteous man. The association with Noah and Job suggests that he lived a long time before Ezekiel. The protagonist of the Biblical Book of Daniel, however, is a younger contemporary of Ezekiel. It may be that he derived his name from the legendary hero, but he cannot be the same person. A figure called Dan’el is also known from texts found at Ugarit, in northern Syrian, dating to the second millennium BCE. He is the father of Aqhat, and is portrayed as judging the cause of the widow and the fatherless in the city gate. This story may help explain why the name Daniel is associated with wisdom and righteousness in the Hebrew Bible. The name means “God is my judge,” or “judge of God.” Daniel acquires a new identity, however, in the Book of Daniel. As found in the Hebrew Bible, the book consists of 12 chapters. The first six are stories about Daniel, who is portrayed as a youth deported from Jerusalem to Babylon, who rises to prominence at the Babylonian court. The second half of the book recounts a series of revelations that this Daniel received and were interpreted for him by an angel. -

Notes on Amos 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Amos 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE AND WRITER The title of the book comes from its writer. The prophet's name means "burden-bearer" or "load-carrier." Of all the 16 Old Testament writing prophets, only Amos recorded what his occupation was before God called him to become a prophet. Amos was a "sheepherder" (Heb. noqed; cf. 2 Kings 3:4) or "sheep breeder," and he described himself as a "herdsman" (Heb. boqer; 7:14). He was more than a shepherd (Heb. ro'ah), though some scholars deny this.1 He evidently owned or managed large herds of sheep, and or goats, and was probably in charge of shepherds. Amos also described himself as a "grower of sycamore figs" (7:14). Sycamore fig trees are not true fig trees, but a variety of the mulberry family, which produces fig-like fruit. Each fruit had to be scratched or pierced to let the juice flow out so the "fig" could ripen. These trees grew in the tropical Jordan Valley, and around the Dead Sea, to a height of 25 to 50 feet, and bore fruit three or four times a year. They did not grow as well in the higher elevations such as Tekoa, Amos' hometown, so the prophet appears to have farmed at a distance from his home, in addition to tending herds. "Tekoa" stood 10 miles south of Jerusalem in Judah. Thus, Amos seems to have been a prosperous and influential Judahite. However, an older view is that Amos was poor, based on Palestinian practices in the nineteenth century. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

The Book of Daniel Its Historical Trustworthiness and Prophetic Character

G. Ch. Aalders, “The Book of Daniel: Its Historical Trustworthiness and Prophetic Character,” The Evangelical Quarterly 2.3 (July 1930): 242-254. The Book of Daniel Its Historical Trustworthiness and Prophetic Character G. Ch. Aalders [p.242] In the January issue of this periodical I endeavoured to throw light upon the turn of the tide which has been accomplished in Pentateuchal criticism during the last decennia. I now want to draw the attention of our readers to another problem of the Old Testament which has been of no less importance in negative Bible criticism. The vast majority of Old Testament students have been wont to deny to the Book of Daniel any historical value and to dispute its real prophetic character. In the case of this book it again was regarded as one of the most certain and unshakable results of scientific research, that it could not have originated at an earlier date than the Maccabean period, and, therefore, neither be regarded as a trustworthy witness to the events it mentions, nor be accepted as a proper prediction of the future it announces. Now as to this date, criticism certainly is receding; and this retreat is characterised by the fact that, in giving up the unity of the book, for some parts a considerably higher age is accepted. Meinhold took the lead: he separated the narrative part (chs. ii-vi) from the prophetic part (chs. vii-xii), and leaving the latter to the Maccabean period claimed for the former a date about 300 B.C.1 Various scholars followed, e.g. -

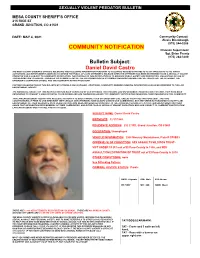

Daniel David Castro Community Bulletin

SEXUALLY VIOLENT PREDATOR BULLETIN MESA COUNTY SHERIFF’S OFFICE 215 RICE ST GRAND JUNCTION, CO 81501 DATE: MAY 4, 2021 Community Contact: Alexis Brumbaugh (970) 244-3206 COMMUNITY NOTIFICATION Division Supervisor: Sgt. Brian Prunty (970) 244-3280 Bulletin Subject: Daniel David Castro THE MESA COUNTY SHERIFF’S OFFICE IS RELEASING THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION PURSUANT TO COLORADO REVISED STATUTES 16-13-901 THROUGH 16-13-905, WHICH AUTHORIZES LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES TO INFORM THE PUBLIC OF A SEX OFFENDER’S RELEASE WHEN THE OFFENDER HAS BEEN DETERMINED TO BE A SEXUALLY VIOLENT PREDATOR AND IS SUBJECT TO COMMUNITY NOTIFICATION. THE PURPOSE OF THIS NOTIFICATION IS TO ENHANCE PUBLIC SAFETY AND PROTECTION. VIGILANTISM, OR USE OF THIS INFORMATION TO HARASS, THREATEN, OR INTIMIDATE ANY OF THE FOLLOWING PEOPLE IS CRIMINAL BEHAVIOR AND WILL NOT BE TOLERATED: THE OFFENDER, THE OFFENDER'S SIGNIFICANT OTHERS, AND THE COMMUNITY NOTIFICATION TEAM. FURTHER DISSEMINATION OF THIS BULLETIN BY CITIZENS IS DISCOURAGED. ADDITIONAL COMMUNITY MEMBERS NEEDING INFORMATION SHOULD BE REFERRED TO THE LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCY. THE INDIVIDUAL SUBJECT OF THIS NOTIFICATION HAS BEEN CONVICTED OF SEX OFFENSES THAT REQUIRE LAW ENFORCEMENT REGISTRATION. FURTHER, THEY HAVE BEEN DETERMINED TO PRESENT A HIGH POTENTIAL TO RE-OFFEND AND ARE THEREFORE SUBJECT TO COMMUNITY NOTIFICATION REGARDING THEIR RESIDENCE IN THIS COMMUNITY. THIS LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCY HAS NO LEGAL AUTHORITY TO DIRECT WHERE A SEX OFFENDER MAY LIVE. UNLESS COURT RESTRICTIONS EXIST, THEY ARE CONSTITUTIONALLY FREE TO LIVE WHEREVER THEY CHOOSE. SEX OFFENDERS HAVE ALWAYS LIVED IN OUR COMMUNITIES, BUT THEY WERE NOT REQUIRED TO NOTIFY LAW ENFORCEMENT OF THEIR RESIDENCE UNTIL REGISTRATION LAWS WERE IMPLEMENTED PURSUANT TO THE JACOB WETTERLING ACT IN 1994. -

Daniel Jeremiah Conference Call Transcript

NFL Network Media Conference Tuesday, March 9, 2021 Daniel Jeremiah It's going to be fascinating to see what happens in free agency. The expectation is we're going to see a lot more THE MODERATOR: Good afternoon, everyone. Thank names pop up over this week as teams try and get under you for joining us on today's call with NFL Network analyst the yet-to-be-determined salary cap. I can't remember a Daniel Jeremiah. I wanted to provide some information on time this late in the process where there was less known, a few NFL Network programming notes. Throughout the but it's going to make it a really fun spring here as we month of March NFL Network provides coverage of pro march towards the draft. days from around the country with a special additions of Path to the Draft hosted by Daniel, Bucky Brooks, Rhett Again, thank you guys for joining us, and fire away. Lewis, and others. Q. What is the white helmet behind you? Coverage of pro days this week includes Clemson and Texas on Thursday, March 11 at 5:00 p.m. eastern time DANIEL JEREMIAH: That's App State. That's the and North Dakota State and Oklahoma on Friday, March all-Americana Appalachian State helmet right there. 12 at 12:00 noon eastern time. Please follow @NFLmedia on Twitter for further details. Q. First, news today, Kenny Golladay, the Lions are going to let him test free agency, so firmly would put Additionally daily editions of Path to the Draft air Monday wide receiver at No. -

Interview with Daniel David Moses Craig Walker

*44/ 114 Interview with Daniel David Moses Craig Walker DANIEL DAVID A strong infuence? A friend noticed a quote from Shake- ould you describe the circumstances speare somewhere in Almighty Voice and His Wife. And I do under which you wrote “Still Septem- keep going to productions of Chekhov &didn’t he insist ber?” they were comedies?& even though until recently Ca- C nadian productions usually made them sombre. Tough DANIEL DAVID her own plays weren’t as interesting, Gwendolyn MacEw- I had agreed with folks at the NAC to contrib- en’s poetry stays with me. And I still remember a student ute to educational materials about indigenous production of Endgame I saw in the Burton Auditorium at culture they were compiling by writing an York as an undergrad. It was clown-ish in a good way. essay about the characteristics of indigenous theatre. Ten my father died and I no longer Q: I think of you as a person who feels a strong responsi- felt I could write any essay. I asked, consider- bility to community, including naturally, to the Indigenous ing the situation, if I could contribute a short community. Do you think that such a sense of responsibil- play and they agreed. Specifc details from ity is an asset or a burden to a creative writer? my and my family’s experience of my father’s passing came together for me. DANIEL DAVID An asset. Where else do you fnd enough stories? Once Q: You are probably as well known in Canada you as an artist have matured sufciently to express your as a poet as you are as a playwright: can you own self, the story of that self really can(t support a conti- explain how you decide whether a particular nuing interest&that(s my perception of my self, of cour- subject, such as this one, is beter suited to a se& unless it(s considered in the context of or in confict poetic or a dramatic treatment? with a community. -

Daniel 14:23-42

FROM THE BOOK OF DANIEL Chapter 14:23-42 There was a great dragon which the Babylonians worshiped. “Look!” said the king to Daniel, “you cannot deny that this is a living god, so adore it.” But Daniel answered, “I adore the Lord, my God, for he is the living God. Give me permission, O king, and I will kill this dragon without sword or club.” “I give you permission,” the king said. Then Daniel took some pitch, fat, and hair; these he boiled together and made into cakes. He put them into the mouth of the dragon, and when the dragon ate them, he burst asunder. “This,” he said, “is what you worshiped.” When the Babylonians heard this, they were angry and turned against the king. “The king has become a Jew,” they said; “he has destroyed Bel, killed the dragon, and put the priests to death.” They went to the king and demanded: “Hand Daniel over to us, or we will kill you and your family.” When he saw himself threatened with violence, the king was forced to hand Daniel over to them. They threw Daniel into a lions’ den, where he remained six days. In the den were seven lions, and two carcasses and two sheep had been given to them daily. But now they were given nothing, so that they would devour Daniel. In Judea there was a prophet, Habakkuk; he mixed some bread in a bowl with the stew he had boiled, and was going to bring it to the reapers in the field, when an angel of the Lord told him, “Take the lunch you have to Daniel in the lions’ den at Babylon.” But Habakkuk answered, “Babylon, sir, I have never seen, and I do not know the den!” The angel of the Lord seized him by the crown of his head and carried him by the hair; with the speed of the wind, he set him down in Babylon above the den. -

Bartimaeus Hector Avalos Iowa State University, [email protected]

Philosophy and Religious Studies Publications Philosophy and Religious Studies 2006 Bartimaeus Hector Avalos Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/philrs_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Other Religion Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ philrs_pubs/6. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy and Religious Studies at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy and Religious Studies Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bartimaeus Abstract "Son of Timaeus." A blind beggar healed by Jesus as the latter exits Jericho (Mark 10:46-52). Disciplines Biblical Studies | History of Religion | Other Religion Comments This is a encyclopedia entry from The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible 1 (2006): 403. Posted with permission. This book chapter is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/philrs_pubs/6 BaftlDlaetus 403 Baruch, Book of :JARTIMAEUS bahr'tuh-mee'uhs [BapTtiJalos Bar· An introduction (1:1-14) is followed by a public prayer :tiJnaios]. "Son of Timaeus." A blind beggar healed of penitence (1: 15-3:8). After the prayer concludes by py jesus as the latter exits Jericho (Mark 10:46-52). highlighting Mosaic law and the obedience it elicits, the ~'hereafter, Bartlmaeus follows Jesus, presumably into third section (3:9-4:4) follows in the form of a poem ~em. -

The Fulfillment of Joel 2:28–32: a Multiple-Lens Approach Daniel J. Treier*

JETS 40/1 (March 1997) 13–26 THE FULFILLMENT OF JOEL 2:28–32: A MULTIPLE-LENS APPROACH DANIEL J. TREIER* Peter’s citation of Joel 2:28–32 in Acts 2:16–21 is a signi˜cant text for our attempts to de˜ne the relationship between Israel and the Church and to understand God’s eschatological program. Pivotal questions concerning the Joel text include how wide its application is, how to interpret its apoca- lyptic imagery, and whether it was ful˜lled on the day of Pentecost when Peter cited it. Three major positions have emerged in response to these questions. Typ- ical of a dispensational approach is A. C. Gaebelein: Careless and super˜cial expositors have often stated that Peter said that all this happened in ful˜llment of what was spoken by Joel. He did not use the word ful˜lled at all. Had he spoken of a ful˜llment then of Joel’s prophecy, he would have uttered something which was not true, for the great prophecy of Joel was not ful˜lled on that day.1 In this understanding, Peter uses Joel 2 as an analogy or rhetorical device but as nothing more. Alternatively, John Stott presents a more covenantal approach: “We must be careful not to requote Joel’s prophecy as if we are still awaiting its ful- ˜lment, or even as if its ful˜lment has been only partial, and we await some future and complete ful˜lment.”2 While Stott has recognized the reality of a Pentecost ful˜llment, this position typically extends the ful˜llment to include the apocalyptic imagery as well. -

The Story of Daniel

Lexomics: The Story of Daniel Lexomics: The Story of Daniel (Slide 1) The Book of Daniel, The Dover Bible, Latin (Slide 2) The Old Testament book of Daniel tells the story of the prophet Daniel and the Israelite exiles in King Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon. The two most famous episodes are the stories of the three youths in the fiery furnace and Daniel in the lion’s den. Biblical Daniel (Latin Vulgate or Vetus Latina) Prayer of Three Youths Azarias Canticum trium Oratio Azariae puerorum Anglo-Saxon Daniel (Slide 3) The Anglo-Saxon poem Daniel is a verse adaptation of the biblical story, found in the 10th century Junius manuscript. In addition to the Old Testament tale, the Anglo-Saxon poet drew on two Latin canticles. (A canticle is a short hymn or song written for church services.) Both the Oratio Azariae and the Canticum trium puerorum were canticles previously adapted from the biblical Daniel as early as the fifth century. The Oratio Azariae is Azarias’ prayer for deliverance from the fiery furnace, and the Canticum trium puerorum is the song of praise that the three youths sing after emerging unscathed from the fire. When the poet wrote Daniel, he adapted the Latin prose of the Bible into Anglo-Saxon poetry, but when he reached the song of Azarias and the song of the three youths, he drew upon the canticles for these sections of the text rather than relying solely on the original biblical source. Junius Manuscript, Anglo-Saxon (Slide 4) Scholars figured out the history of the composition of the Old English Daniel by painstakingly comparing the precise arrangement of scenes in the canticles to the arrangement in the Bible, paying close attention to the linguistic details of the text.