Island Poetry Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALTA Newsletter

Newsletter March 2015 Volume 22 Issue 1 ALTA NEWS March 2015 Volume 22 Issue 1 Inside this issue: Level 1 lessons 3 ready to go Online Bocas writers’ 4 series a big success Level 3 make 6 discoveries in Caribbean Beat More $$ to 7 sponsor a student It’s coming: ALTA’s website has a new look and will soon be ready to make its debut on the web. BELMONT 624-2582/3442 Mon-Thurs: [email protected] 84 Belmont Circular Road 8am-5pm Fri: 8am-4pm SAN FERNANDO 653-4656 St. Paul’s Anglican Church Hall, Mon & Friday: [email protected] 3rd Floor, 12 Harris Promenade 9:00am-4:00pm Emmanuel Marcano Wed 9:00am-5:00pm ARIMA 664-2582 Mon & Wed [email protected] Arima PTSC Terminal Mall 8am-3pm Carolyn Hepburn Fri 9am-5pm www.alta-tt.org Newsletter March 2015 Volume 22 Issue 1 VCTT RISES TO THE CHALLENGE, RALLIES New Look for ALTA Website VOLUNTEERS Anyone visiting ALTA’s website recently (www.alta-tt.org) would Volunteer recruitment has had have found a strange message about the site being unavailable. some challenges this year. Just Don’t worry. The site has been temporary disabled to make way when it seemed there would be a for the redesigned ALTA website, set to be launched in Term 3. small training session, ALTA got a The new layout, with more colour and photos, are in step with call at the beginning of February ALTA’s move to increase our use of information technology. from Volunteer Centre of Trinidad and Tobago (VCTT) President ALTA’s remodeled home on the web will continue to have all the Giselle Mendez offering to partner tutor resources and information for those wanting to know with ALTA to sustain our tutor base more about our programmes — plus additional features. -

MW Bocasjudge'stalk Link

1 Bocas Judge’s talk To be given May 4 2019 Marina Warner April 27 2019 The Bocas de Dragon the Mouths of the Dragon, which give this marvellous festival its name evoke for me the primary material of stories, songs, poems in the imagination of things which isn’t available to our physical senses – the beings and creatures – like mermaids, like dragons – which every culture has created and questioned and enjoyed – thrilled to and wondered at. But the word Bocas also calls to our minds the organ through which all the things made by human voices rise from the inner landscapes of our being - by which we survive, breathe, eat, and kiss. Boca in Latin would be os, which also means bone- as Derek Walcott remembers and plays on as he anatomises the word O-mer-os in his poem of that name. Perhaps the double meaning crystallises how, in so many myths and tales, musical instruments - flutes and pipes and lyres - originate from a bone, pierced or strung to play. Nola Hopkinson in the story she read for the Daughters of Africa launch imagined casting a spell with a pipe made from the bone of a black cat. When a bone-mouth begins to give voice – it often tells a story of where it came from and whose body it once belonged to: in a Scottish ballad, to a sister murdered by a sister, her rival for a boy. Bone-mouths speak of knowledge and experience, suffering and love, as do all the writers taking part in this festival and on this splendid short list. -

April – June 2012 Alumni Association (T&T Chapter) 751-0741 Mr

ST. AUGUSTINE NEWS STAN 2012 THE TIPPING POINT Malcolm Gladwell speaks at UWI graduate school TAKING DIRECTION Award-winning Film Director Renee Pollonais KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER Research Development Fund brings new opportunities BREAKING THE SILENCE child sexual abuse www.sta.uwi.edu/stan Campus Correspondents THE UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES 16 ST. AUGUSTINE CAMPUS Alma Jordan Library Exts. 82336/82337 (STARRS)/3600 (UEC) Ms. Allison Dolland April – June 2012 Alumni Association (T&T Chapter) 751-0741 Mr. Maurice Burke Arthur Lok Jack Graduate School of Business 662-9894 / 645-6700 Ext. 341 Ms. Adi Montas Bursary Ext. 83382 Mrs. Renee Sewalia Campus Bookshop Exts. 83520/83521 Ms. Michelle Dennis Campus Information Technology Centre (CITS) Ext. 83227 Mr. Nazir Alladin CARDI 645-1205 Ext. 8251 Anna Walcott-Hardy Mr. Selwyn King Editor CARIRI 662-7161/2 Ms. Irma Burkett Serah Acham Caribbean Centre for Monetary Studies (CCMS) Ext. 82544 Cristo Adonis Mrs. Kathleen Charles Dr Jo-Anne S. Ferreira Campus Projects Office (CPO) Ext. 82411 Mr. Alfred Reid Stacy Richards-Kennedy Centre for Criminology & Criminal Justice Sylvia Moodie-Kublalsingh Exts. 82019/82020 Mr. Omardath Maharaj 32 Ira Mathur Centre for Gender & Dev. Studies Exts. 83573/83548 Christie Sabga Ms. Donna Drayton Margaret Walcott Distance Education Centre (UWIDEC) Ext. 82430 Anna Walcott-Hardy Ms. Colleen Johnson Karen Wickham Division of Facilities Management Ext. 82054 Mr. Suresh Maharaj Contributing Writers Engineering Exts. 83073/82170 Dr. Hamid Farabi/Dr. Clement Imbert Johann Bennett Engineering Institute Exts. 83171/82197/82175 Sales Assistant Dr. Edwin Ekwue Guild of Students (GOS) 743-2378 Myriam Chancy Mr. Mervin Alwyn Agiste Humanities & Education Exts. -

THE NATIONAL GAS COMPANY of TRINIDAD and TOBAGO LIMITED MEDIA RELEASE NGC Bocas Lit Fest South Launched November 7Th 2016 Tradew

THE NATIONAL GAS COMPANY OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO LIMITED MEDIA RELEASE NGC Bocas Lit Fest South Launched November 7th 2016 Tradewinds Hotel was the site for the launch of 2016’s NGC Bocas Lit Fest (South) on Saturday 5th November 2016. NGC’s President, Mr. Mark Loquan, was the main speaker at the event. To an audience which included, Marina Salandy-Brown, Bocas Lit Fest founder & director; Michael Anthony, eminent author of Green days by the River fame; Sherid Mason, Chairman, San Fernando Arts Council (SFAC) and NGC Bocas Lit Fest South partners; Shella Murray, Vice- Chairman, San Fernando Arts Council (SFAC) and Ras Commander, Chairman, TUCO, Mr. Loquan expressed that NGC was “gratified by the success of this investment, especially given the challenges facing our business sector and the concomitant need for prudent expenditure. It is much easier to justify support for an organisation when it demonstrates consistent growth, when it addresses an underserviced need and when it delivers tangible results.” The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) has been partnering with the NGC Bocas Lit Fest since 2011. NGC’s support has grown from being that of a major sponsor in 2011 to title sponsor since 2012. For the past four years, the NGC Bocas Lit Fest has been one of NGC’s flagship investments within its Corporate Social Responsibility portfolio. Attendance at the NGC Bocas Lit Fest has grown from its inaugural 2011 figure of just over 3,000 to over 6,500 persons in 2015. The Festival allows the country and the region to showcase the talent and creativity via literature, films, music and speech. -

Download the Application Form, Visit

Let the Weeds Grow UWI researchers have got mind-blowing results from tests using seaweed as bio stimulants. A gold mine for agriculture might be floating up on our shores. See Page 8 ACHIEVER – 04 UP AHEAD – 07 CONFERENCE – 11 Sarika’s Success HONOURS – 04 New Dimensions Nelson’s Island A young actuary on the rise A campus you’ve never seen What rainbow to reef means Our Honorees The Bass Man in our head SUNDAY 5 AUGUST, 2018 – UWI TODAY 3 FROM THE PRINCIPAL The Best Time to Plant a Tree The term ‘Urban on street trees and their effect on driving behaviour, Greening’ embraces safety perception and speed in urban or suburban activities such as public areas. They surmised that tree-lined streets are safer in landscaping and the both urban and suburban areas. In addition, individual creation of urban forestry driving speeds were significantly lower in the suburban that seek to ‘green’ settings with trees. In other words, trees calm traffic and soften the urban and reduce the frequency and severity of crashes. This landscape and make it, research suggests that, quite apart from the aesthetic as they say, more ‘people appeal, there is validity – from a safety perspective – in friendly’. These greening having trees on our streets and highways. You may recall initiatives include there was a bit of an outcry when the trees lining the planting road verges and median of the highway between Curepe and Valsayn, islands with indigenous vegetation, removal of alien were removed. I am therefore pleased to note that Works species, upgrading of parks and gardens in inner city and Transport Minister, Rohan Sinanan, has promised areas, development of urban trails passing through that trees will be replanted once the new interchange is green areas, and getting landscape architects to design completed. -

Faculty Report 2013/2014

FACULTY REPORT 2013/2014 FACULTY OF ENGINEERING 02 FACULTY OF FOOD & AGRICULTURE 16 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES & EDUCATION 26 FACULTY OF LAW 44 FACULTY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES 50 FACULTY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 62 FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES 78 CENTRES & INSTITUTES 90 PUBLICATIONS AND CONFERENCES 134 1 Faculty of Engineering Professor Brian Copeland Dean, Faculty of Engineering Executive Summary For the period 2013-2014, the Faculty of Engineering continued its major activities in areas such as Curriculum and Pedagogical Reform (CPR) at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, Research and Innovation, and providing Support Systems (Administrative and Infrastructure) in keeping with the 2012-2017 Strategic Plan. FACULTY OF ENGINEERING TEACHING & LEARNING Accreditation Status New GPA During the year under review, the BSc Petroleum The year under review was almost completely Geoscience and MSc Petroleum Engineering dedicated to planning for the transition to a new GPA programmes were accredited by the Energy Institute, system scheduled for implementation in September UK. In addition, the relatively new Engineering Asset 2014. The Faculty adopted an approach where the new Management programme was accredited for the GPA system was applied to new students (enrolled period 2008 to 2015, thus maintaining alignment September 2014) only. Continuing students remain with other iMechE accredited programmes in the under the GPA system they encountered at first Department. registration. The Faculty plans to implement the new GPA scheme on a phased basis over the next academic The accreditation status of all BSc programmes and year so that by 2016–2017, all students will be under the those MSc programmes for which accreditation was new scheme. -

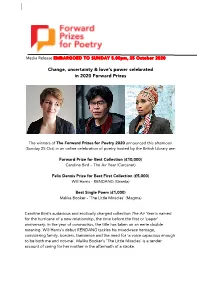

Change, Uncertainty & Love's Power Celebrated in 2020 Forward Prizes

Media Release EMBARGOED TO SUNDAY 5.00pm, 25 October 2020 Change, uncertainty & love’s power celebrated in 2020 Forward Prizes The winners of The Forward Prizes for Poetry 2020 announced this afternoon (Sunday 25 Oct) in an online celebration of poetry hosted by the British Library are: Forward Prize for Best Collection (£10,000) Caroline Bird – The Air Year (Carcanet) Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection (£5,000) Will Harris - RENDANG (Granta) Best Single Poem (£1,000) Malika Booker - ‘The Little Miracles’ (Magma) Caroline Bird’s audacious and erotically charged collection The Air Year is named for the hurricane of a new relationship, the time before the first or ‘paper’ anniversary: in the year of coronavirus, the title has taken on an eerie double meaning. Will Harris’s debut RENDANG tackles his mixed-race heritage, considering family, borders, transience and the need for ‘a voice capacious enough to be both me and not-me’. Malika Booker’s ‘The Little Miracles’ is a tender account of caring for her mother in the aftermath of a stroke. 2 The chair of the 2020 jury, writer, critic and cultural historian Alexandra Harris, commented: ‘We are thrilled to celebrate three winning poets whose finely crafted work has the protean power to change as it meets new readers.’ The Forward Prize for Poetry, founded by William Sieghart and run by the charity Forward Arts Foundation, are the most prestigious awards for new poetry published in the UK and Ireland, and have been sponsored since their launch in 1992 by the content marketing agency, Bookmark (formerly Forward Worldwide). -

NGC Bocas Lit Fest 2013 ‘A Great Gift to Our Country’

NGC Bocas Lit Fest 2013 ‘A great gift to our country’ Barbara Jenkins wins the inaugural Hollick Arvon Caribbean Guyanese author Rupert Roopnaraine wins the Writers’ Prize. Ruth Borthwick of Arvon (right) and The Sky’s Wild St Lucian poet Kendel Hyppolyte smiles radiantly as he Monique Roffey accepts the OCM Bocas Prize for CaribbeanArchipelago. Non-Fiction OCM Bocas Prize for Fault Lines. Dr Funso Aiyejina, writer and critic (left) present the award. is presented with the OCM Bocas Prize for his collection Literature at NGC Bocas Lit Fest 2013 for her work Noise: Selected Essays. The Winner Effect: The Science of Author Prof Ian Robertson autographs at a special a booking copy of signing at the National Library. the Mind and How to Use It ongratulations to the 2013 NGC Bocas Lit CFest for providing the country’s most vibrant, artistic showcase for the third straight year! Scores of Caribbean and international authors, readers, orators and performers brought their energy to the annual literary festival, making it Cassandra Patrovani Sylvester, NGC’s VP Human a powerful gathering of creative excellence. and Corporate Relations, speaks at the NGC Bocas Lecture: The Big Idea, in which “An embarrassment of riches” was how Prof Ian Robertson was the feature speaker. Trinidadian journalist, Andre Bagoo described Overall chair of the awards committee his experience at the NGC Bocas Lit Fest in his Edinburgh World Writers’ Conference panellists: (l-r) Chair Ifeona Fulani, Pankaj Mishra, Courttia Newland, and Jamaican author, Olive Senior. Catherine Belshaw, Literary Awards Officer Earl Lovelace and Olive Senior. Photo by Maria Nunes, Official Festival Photographer blog http://pleasurett.blogspot.com. -

Download the Guide to Kei Miller's Writers

Introducing ten unmissable emerging writers Kei Miller offers you a guide to contemporary British writing Ideas for your next festival, reading programme, or inspiration for your students Contents Your guide to contemporary British 1nta writing... 3 Kei Miller introduces his selection 4cts Caleb Azumah Nelson 5 Sairish Hussain 6 Daisy Lafarge 7 Rachel Long 8 Steven Lovatt 9 Mícheál McCann 10 Helen McClory 11 Gail McConnell 12 Jarred McGinnis 13 Ingrid Persaud 14 Vahni Capildeo on Kei Miller’s selection 15 Reception 17 Elif Shafak’s selection of 10 exciting women writers 19 Val McDermid’s selection of 10 compelling 20 LGBTQI+ writers Jackie Kay’s selection of 10 compelling 21 Black, Asian and ethnically diverse writers Owen Sheers’ selection of 10 writers asking 22 questions to shape our future The International Literature Showcase is a partnership between the National Centre for Writing and British Council, with support from Arts Council England and Creative Scotland. Your guide to contemporary British writing... Looking to book inspiring writers for your next festival? Want to introduce your students to exciting new writing from the UK? The International Literature Showcase is a partnership between the National Centre for Writing and British Council. It aims to showcase amazing writers based in the UK to programmers, publishers and teachers of literature in English around the world. To do so, we have invited five leading writers to each curate a showcase of themed writing coming out of the UK today. Following the high-profile launch of Elif Shafak’s showcase of women writers at London Book Fair, Val McDermid’s LGBTQI+ writers at the National Library of Scotland, Jackie Kay’s Black, Asian and ethnically diverse (BAED) writers at Manchester Literature Festival, and Owen Sheers’ writers asking questions that will shape our future at Norfolk & Norwich Festival, we have now revealed our final showcase: Kei Miller’s selection of ten unmissable emerging writers working in the UK today. -

Global Report

AN60 Spotlight Trinidad and Tobago “Our progressive economy is consistently bolstered by our international reputation as a peaceful and stable democratic nation” IntervIew The Honourable Kamla Persad-Bissessar, SC, MP, Prime Minister of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago Trinidad and Tobago’s prime minister, Kamla Persad-Bissessar, talks to Global about her plans for strengthening and di- versifying the economy away from its de- pendency on oil and gas reserves. She has high hopes of enhancing competitiveness through legislative and institutional re- forms, and strongly believes that expanding trade relations with Latin America and the new emerging economies is the way for- ward. Persad-Bissessar also touches on the rise of women’s participation in parliament, and reveals planned measures to tackle the big challenge in the country’s education system – that of boys’ underachievement. Global: For 2013, the World Bank has ranked Trinidad and Tobago at 69 of 185 countries for doing business. This is one step up from 2012, but still an uncom- petitive ranking for a country seeking to attract new foreign investment and encour- age local investors. What concrete steps are your government taking to improve the conditions for doing business? Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bisses- sar: Improving the ease of doing business in Trinidad and Tobago is a priority for the government of Trinidad and Tobago. In this regard, a series of reforms are be- ing aggressively pursued. [For example,] implementation of a Single Electronic Window for Trade and Business Facili- tation. This IT platform, which became operational in February 2012, links over ten government departments in delivering key business-related e-services (such as e- fiscal incentives, e-import/export licences and permits, e-company registration, e- work permits and e-certificates of origin for exporters) in real time to the business community. -

A Benefit Event

2018 VIRGIN ISLANDS LITERARY FESTIVAL & BOOK FAIR A BENEFIT EVENT Here we are on the other side of two category five hurricanes weaving together the strands of the 4th Virgin Islands Literary Festival and Book Fair 2018--- billed as a benefit event with an abbreviated itinerary scheduled for April 13 and 14. Over the years, there were a number of events at the University of the Virgin Islands aimed at bringing authors and books together; however, the idea of establishing an annual Literary Festival and Book Fair is credited to Dr. Simon Jones- Hendrickson, former Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences (CLASS). The first Program Chair was UVI Professor Dr. Valerie Knowles Combie. The 2018, program chair for the third year in succession is Alscess Lewis-Brown, UVI Professor and Editor of The Caribbean Writer. “We are aiming to make this abbreviated version of our treasured festival an unforgettable event,” Brown said with decided enthusiasm. “And our central theme: “Rough Tides, Tough Times: Reflections and Transitions” is both a gesture to and a capitalizing on our all-around tumultuous transition into 2018.” As in the past, the festival is a toast to ideas and a celebration of the imagination through literature, panel discussions and workshops on writing and publishing. This year, there will be a special emphasis on photography and film production.” Main events will be held on the island of St. Croix on the Albert Sheen Campus of the University of the Virgin Islands. There will also be several other venues including the Caribbean Museum Center for the Arts on the waterfront in Frederiksted, Balter’s St Croix Restaurant in Christiansted and, for the first time, UVI’s St. -

Literary Correspondence: Letters and Emails in Caribbean Writing Marta Fernández Campa

Literary Correspondence: Letters and emails in Caribbean writing Marta Fernández Campa Abstract This article explores the role of correspondence (and literary archives in general) in illuminating central aspects of Caribbean literary culture and authors’ work, with a consideration of the challenges and the need to preserve email correspondence for archives in the future. This study is part of a larger three-year Leverhulme research project, Caribbean Literary Heritage, now in its initial stage. Led by Professor Alison Donnell (University of East Anglia) with Professor Kei Miller (University of Exeter), with consultancy support from Dr David Sutton (University of Reading), the project focuses on the recovery research of forgotten or less known Caribbean writers and a study of the development of literary archives across generations to explore authors’ recordkeeping practices, and the new challenges and possibilities created by born-digital papers. Author Marta Fernández Campa is a Senior Research Associate at the University of East Anglia. She has previously worked at the University of Reading and the University of Saint Louis, Madrid campus. Her research focuses on literary archives, digital preservation and the role of archival records in writer’s creative work. She has published articles in Arc, Anthurium, Caribbean Beat and Small Axe, and has been the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship and the Center for the Humanities Fellowship at the University of Miami. Introduction Caribbean literary archives hold great value for understanding