Overcoming Inhibition in the Spindle Checkpoint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitosis Vs. Meiosis

Mitosis vs. Meiosis In order for organisms to continue growing and/or replace cells that are dead or beyond repair, cells must replicate, or make identical copies of themselves. In order to do this and maintain the proper number of chromosomes, the cells of eukaryotes must undergo mitosis to divide up their DNA. The dividing of the DNA ensures that both the “old” cell (parent cell) and the “new” cells (daughter cells) have the same genetic makeup and both will be diploid, or containing the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. For reproduction of an organism to occur, the original parent cell will undergo Meiosis to create 4 new daughter cells with a slightly different genetic makeup in order to ensure genetic diversity when fertilization occurs. The four daughter cells will be haploid, or containing half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. The difference between the two processes is that mitosis occurs in non-reproductive cells, or somatic cells, and meiosis occurs in the cells that participate in sexual reproduction, or germ cells. The Somatic Cell Cycle (Mitosis) The somatic cell cycle consists of 3 phases: interphase, m phase, and cytokinesis. 1. Interphase: Interphase is considered the non-dividing phase of the cell cycle. It is not a part of the actual process of mitosis, but it readies the cell for mitosis. It is made up of 3 sub-phases: • G1 Phase: In G1, the cell is growing. In most organisms, the majority of the cell’s life span is spent in G1. • S Phase: In each human somatic cell, there are 23 pairs of chromosomes; one chromosome comes from the mother and one comes from the father. -

Mitosin/CENP-F in Mitosis, Transcriptional Control, and Differentiation

Journal of Biomedical Science (2006) 13: 205–213 205 DOI 10.1007/s11373-005-9057-3 Mitosin/CENP-F in mitosis, transcriptional control, and differentiation Li Ma1,2, Xiangshan Zhao1 & Xueliang Zhu1,* 1Laboratory of Molecular Cell Biology, Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, 200031, China; 2Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100039, China Ó 2006 National Science Council, Taipei Key words: differentiation, kinetochore, mitosis, transcription Summary Mitosin/CENP-F is a large nuclear/kinetochore protein containing multiple leucine zipper motifs poten- tially for protein interactions. Its expression levels and subcellular localization patterns are regulated in a cell cycle-dependent manner. Recently, accumulating lines of evidence have suggested it a multifunctional protein involved in mitotic control, microtubule dynamics, transcriptional regulation, and muscle cell differentiation. Consistently, it is shown to interact directly with a variety of proteins including CENP-E, NudE/Nudel, ATF4, and Rb. Here we review the current progress and discuss possible mechanisms through which mitosin may function. Mitosin, also named CENP-F, was initially iden- acid residues (GenBank Accession No. CAH73032) tified as a human autoimmune antigen [1, 2] and [3]. The gene expression is cell cycle-dependent, as an in vitro binding protein of the tumor suppressor the mRNA levels increase following S phase Rb [3, 4]. Its dynamic temporal expression and progression and peak in early M phase [3]. Such modification patterns as well as ever-changing patterns are regulated by the Forkhead transcrip- spatial distributions following the cell cycle pro- tion factor FoxM1 [5]. -

1 Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Is Sufficient for Complete Cdc20

Spindle assembly checkpoint is sufficient for complete Cdc20 sequestering in mitotic control Bashar Ibrahim Bio System Analysis Group, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, and Jena Centre for Bioinformatics (JCB), 07743 Jena, Germany Email: [email protected] Abstract The spindle checkpoint assembly (SAC) ensures genome fidelity by temporarily delaying anaphase onset, until all chromosomes are properly attached to the mitotic spindle. The SAC delays mitotic progression by preventing activation of the ubiquitin ligase anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) or cyclosome; whose activation by Cdc20 is required for sister-chromatid separation marking the transition into anaphase. The mitotic checkpoint complex (MCC), which contains Cdc20 as a subunit, binds stably to the APC/C. Compelling evidence by Izawa and Pines (Nature 2014; 10.1038/nature13911) indicates that the MCC can inhibit a second Cdc20 that has already bound and activated the APC/C. Whether or not MCC per se is sufficient to fully sequester Cdc20 and inhibit APC/C remains unclear. Here, a dynamic model for SAC regulation in which the MCC binds a second Cdc20 was constructed. This model is compared to the MCC, and the MCC-and-BubR1 (dual inhibition of APC) core model variants and subsequently validated with experimental data from the literature. By using ordinary nonlinear differential equations and spatial simulations, it is shown that the SAC works sufficiently to fully sequester Cdc20 and completely inhibit APC/C activity. This study highlights the principle that a systems biology approach is vital for molecular biology and could also be used for creating hypotheses to design future experiments. Keywords: Mathematical biology, Spindle assembly checkpoint; anaphase promoting complex, MCC, Cdc20, systems biology 1 Introduction Faithful DNA segregation, prior to cell division at mitosis, is vital for maintaining genomic integrity. -

Kinetochores, Microtubules, and Spindle Assembly Checkpoint

Review Joined at the hip: kinetochores, microtubules, and spindle assembly checkpoint signaling 1 1,2,3 Carlos Sacristan and Geert J.P.L. Kops 1 Molecular Cancer Research, University Medical Center Utrecht, 3584 CG Utrecht, The Netherlands 2 Center for Molecular Medicine, University Medical Center Utrecht, 3584 CG Utrecht, The Netherlands 3 Cancer Genomics Netherlands, University Medical Center Utrecht, 3584 CG Utrecht, The Netherlands Error-free chromosome segregation relies on stable and cell division. The messenger is the SAC (also known as connections between kinetochores and spindle microtu- the mitotic checkpoint) (Figure 1). bules. The spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) monitors The transition to anaphase is triggered by the E3 ubiqui- such connections and relays their absence to the cell tin ligase APC/C, which tags inhibitors of mitotic exit cycle machinery to delay cell division. The molecular (CYCLIN B) and of sister chromatid disjunction (SECURIN) network at kinetochores that is responsible for microtu- for proteasomal degradation [2]. The SAC has a one-track bule binding is integrated with the core components mind, inhibiting APC/C as long as incorrectly attached of the SAC signaling system. Molecular-mechanistic chromosomes persist. It goes about this in the most straight- understanding of how the SAC is coupled to the kineto- forward way possible: it assembles a direct and diffusible chore–microtubule interface has advanced significantly inhibitor of APC/C at kinetochores that are not connected in recent years. The latest insights not only provide a to spindle microtubules. This inhibitor is named the striking view of the dynamics and regulation of SAC mitotic checkpoint complex (MCC) (Figure 1). -

Kinetochore Structure, Duplication, and Distribution in Mammalian Cells : Analysis by Human Autoantibodies from Scleroderma Patients

Kinetochore Structure, Duplication, and Distribution in Mammalian Cells : Analysis by Human Autoantibodies from Scleroderma Patients SARI BRENNER, DANIEL PEPPER, M . W. BERNS, E . TAN, and B . R . BRINKLEY Department of Cell Biology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas 77030, High Voltage Electron Microscope Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, Department of Developmental and Cell Biology, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California 92717, and Department of Medicine, University of Colorado, Medical Center, Denver, Colorado 80262 ABSTRACT The specificity of the staining of CREST scleroderma patient serum was investigated by immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy. The serum was found to stain the centromere region of mitotic chromosomes in many mammalian cell types by immunofluores- cence. It also localized discrete spots in interphase nuclei which we have termed "presumptive kinetochores ." The number of presumptive kinetochores per cell corresponds to the chromo- some number in the cell lines observed . Use of the immunoperoxidase technique to localize the antisera on PtK2 cells at the electron microscopic level revealed the specificity of the sera for the trilaminar kinetochore disks on metaphase and anaphase chromosomes . Presumptive kinetochores in the interphase nuclei were also visible in the electron microscope as randomly arranged, darkly stained spheres averaging 0.22 p,m in diameter. Preabsorption of the antisera was attempted using microtubule protein, purified tubulin, actin, and microtubule-associated proteins . None of these proteins diminished the immunofluorescence staining of the sera, indicating that the antibody-specific antigen(s) is a previously unrecognized component of the kinetochore region . In some interphase cells observed by both immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy, the presumptive kinetochores appeared as double rather than single spots . -

Molecular Biology and Applied Genetics

MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND APPLIED GENETICS FOR Medical Laboratory Technology Students Upgraded Lecture Note Series Mohammed Awole Adem Jimma University MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND APPLIED GENETICS For Medical Laboratory Technician Students Lecture Note Series Mohammed Awole Adem Upgraded - 2006 In collaboration with The Carter Center (EPHTI) and The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health Jimma University PREFACE The problem faced today in the learning and teaching of Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology for laboratory technologists in universities, colleges andhealth institutions primarily from the unavailability of textbooks that focus on the needs of Ethiopian students. This lecture note has been prepared with the primary aim of alleviating the problems encountered in the teaching of Medical Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology course and in minimizing discrepancies prevailing among the different teaching and training health institutions. It can also be used in teaching any introductory course on medical Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology and as a reference material. This lecture note is specifically designed for medical laboratory technologists, and includes only those areas of molecular cell biology and Applied Genetics relevant to degree-level understanding of modern laboratory technology. Since genetics is prerequisite course to molecular biology, the lecture note starts with Genetics i followed by Molecular Biology. It provides students with molecular background to enable them to understand and critically analyze recent advances in laboratory sciences. Finally, it contains a glossary, which summarizes important terminologies used in the text. Each chapter begins by specific learning objectives and at the end of each chapter review questions are also included. -

BUB3 That Dissociates from BUB1 Activates Caspase-Independent Mitotic Death (CIMD)

Cell Death and Differentiation (2010) 17, 1011–1024 & 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1350-9047/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/cdd BUB3 that dissociates from BUB1 activates caspase-independent mitotic death (CIMD) Y Niikura1, H Ogi1, K Kikuchi1 and K Kitagawa*,1 The cell death mechanism that prevents aneuploidy caused by a failure of the spindle checkpoint has recently emerged as an important regulatory paradigm. We previously identified a new type of mitotic cell death, termed caspase-independent mitotic death (CIMD), which is induced during early mitosis by partial BUB1 (a spindle checkpoint protein) depletion and defects in kinetochore–microtubule attachment. In this study, we have shown that survived cells that escape CIMD have abnormal nuclei, and we have determined the molecular mechanism by which BUB1 depletion activates CIMD. The BUB3 protein (a BUB1 interactor and a spindle checkpoint protein) interacts with p73 (a homolog of p53), specifically in cells wherein CIMD occurs. The BUB3 protein that is freed from BUB1 associates with p73 on which Y99 is phosphorylated by c-Abl tyrosine kinase, resulting in the activation of CIMD. These results strongly support the hypothesis that CIMD is the cell death mechanism protecting cells from aneuploidy by inducing the death of cells prone to substantial chromosome missegregation. Cell Death and Differentiation (2010) 17, 1011–1024; doi:10.1038/cdd.2009.207; published online 8 January 2010 Aneuploidy – the presence of an abnormal number of of spindle checkpoint activity.20,21 -

Kinetochore Life Histories Reveal the Origins of Chromosome Mis-Segregation and Correction Mechanisms Onur Sen1,+, Jonathan U

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.30.436326; this version posted March 31, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Kinetochore life histories reveal the origins of chromosome mis-segregation and correction mechanisms Onur Sen1,+, Jonathan U. Harrison2,+, Nigel J. Burroughs1,2,*, and Andrew D. McAinsh1,* 1Centre for Mechanochemical Cell Biology and Division of Biomedical Sciences, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom 2Mathematics Institute and Zeeman Institute, University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom *Corresponding authors +These authors contributed equally to this work ABSTRACT Chromosome mis-segregation during mitosis leads to daughter cells with deviant karyotypes (aneuploidy) and an increased mutational burden through chromothripsis of mis-segregated chromosomes. The rate of mis-segregation and the aneuploidy state are hallmarks of cancer and linked to cancer genome evolution. Errors can manifest as “lagging chromosomes” in anaphase, although the mechanistic origins and likelihood of correction are incompletely understood. Here we combine lattice light sheet microscopy, endogenous protein labelling and computational analysis to define the life history of > 104 kinetochores throughout metaphase and anaphase from over 200 cells. By defining the "laziness" of kinetochores in anaphase, we reveal that chromosomes are at a considerable and continual risk of mis-segregation. We show that the majority of kinetochores are corrected rapidly in early anaphase through an Aurora B dependent process. Moreover, quantitative analyses of the kinetochore life histories reveal a unique dynamic signature of metaphase kinetochore oscillations that forecasts their fate in the subsequent anaphase. -

The Genome of Schmidtea Mediterranea and the Evolution Of

OPEN ArtICLE doi:10.1038/nature25473 The genome of Schmidtea mediterranea and the evolution of core cellular mechanisms Markus Alexander Grohme1*, Siegfried Schloissnig2*, Andrei Rozanski1, Martin Pippel2, George Robert Young3, Sylke Winkler1, Holger Brandl1, Ian Henry1, Andreas Dahl4, Sean Powell2, Michael Hiller1,5, Eugene Myers1 & Jochen Christian Rink1 The planarian Schmidtea mediterranea is an important model for stem cell research and regeneration, but adequate genome resources for this species have been lacking. Here we report a highly contiguous genome assembly of S. mediterranea, using long-read sequencing and a de novo assembler (MARVEL) enhanced for low-complexity reads. The S. mediterranea genome is highly polymorphic and repetitive, and harbours a novel class of giant retroelements. Furthermore, the genome assembly lacks a number of highly conserved genes, including critical components of the mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint, but planarians maintain checkpoint function. Our genome assembly provides a key model system resource that will be useful for studying regeneration and the evolutionary plasticity of core cell biological mechanisms. Rapid regeneration from tiny pieces of tissue makes planarians a prime De novo long read assembly of the planarian genome model system for regeneration. Abundant adult pluripotent stem cells, In preparation for genome sequencing, we inbred the sexual strain termed neoblasts, power regeneration and the continuous turnover of S. mediterranea (Fig. 1a) for more than 17 successive sib- mating of all cell types1–3, and transplantation of a single neoblast can rescue generations in the hope of decreasing heterozygosity. We also developed a lethally irradiated animal4. Planarians therefore also constitute a a new DNA isolation protocol that meets the purity and high molecular prime model system for stem cell pluripotency and its evolutionary weight requirements of PacBio long-read sequencing12 (Extended Data underpinnings5. -

List, Describe, Diagram, and Identify the Stages of Meiosis

Meiosis and Sexual Life Cycles Objective # 1 In this topic we will examine a second type of cell division used by eukaryotic List, describe, diagram, and cells: meiosis. identify the stages of meiosis. In addition, we will see how the 2 types of eukaryotic cell division, mitosis and meiosis, are involved in transmitting genetic information from one generation to the next during eukaryotic life cycles. 1 2 Objective 1 Objective 1 Overview of meiosis in a cell where 2N = 6 Only diploid cells can divide by meiosis. We will examine the stages of meiosis in DNA duplication a diploid cell where 2N = 6 during interphase Meiosis involves 2 consecutive cell divisions. Since the DNA is duplicated Meiosis II only prior to the first division, the final result is 4 haploid cells: Meiosis I 3 After meiosis I the cells are haploid. 4 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ Chromosomes condense. Because of replication during interphase, each chromosome consists of 2 sister chromatids joined by a centromere. ¾ Synapsis – the 2 members of each homologous pair of chromosomes line up side-by-side to form a tetrad consisting of 4 chromatids: 5 6 1 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ During synapsis, sometimes there is an exchange of homologous parts between non-sister chromatids. This exchange is called crossing over. 7 8 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis (2N=6) Prophase I: ¾ the spindle apparatus begins to form. ¾ the nuclear membrane breaks down: Prophase I 9 10 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, 4 Possible Metaphase I Arrangements: Metaphase I: ¾ chromosomes line up along the equatorial plate in pairs, i.e. -

Anaphase Bridges: Not All Natural Fibers Are Healthy

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Anaphase Bridges: Not All Natural Fibers Are Healthy Alice Finardi 1, Lucia F. Massari 2 and Rosella Visintin 1,* 1 Department of Experimental Oncology, IEO, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, 20139 Milan, Italy; alice.fi[email protected] 2 The Wellcome Centre for Cell Biology, Institute of Cell Biology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3BF, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-5748-9859; Fax: +39-02-9437-5991 Received: 14 July 2020; Accepted: 5 August 2020; Published: 7 August 2020 Abstract: At each round of cell division, the DNA must be correctly duplicated and distributed between the two daughter cells to maintain genome identity. In order to achieve proper chromosome replication and segregation, sister chromatids must be recognized as such and kept together until their separation. This process of cohesion is mainly achieved through proteinaceous linkages of cohesin complexes, which are loaded on the sister chromatids as they are generated during S phase. Cohesion between sister chromatids must be fully removed at anaphase to allow chromosome segregation. Other (non-proteinaceous) sources of cohesion between sister chromatids consist of DNA linkages or sister chromatid intertwines. DNA linkages are a natural consequence of DNA replication, but must be timely resolved before chromosome segregation to avoid the arising of DNA lesions and genome instability, a hallmark of cancer development. As complete resolution of sister chromatid intertwines only occurs during chromosome segregation, it is not clear whether DNA linkages that persist in mitosis are simply an unwanted leftover or whether they have a functional role. -

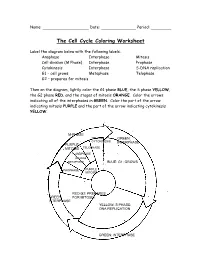

The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet

Name: Date: Period: The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet Label the diagram below with the following labels: Anaphase Interphase Mitosis Cell division (M Phase) Interphase Prophase Cytokinesis Interphase S-DNA replication G1 – cell grows Metaphase Telophase G2 – prepares for mitosis Then on the diagram, lightly color the G1 phase BLUE, the S phase YELLOW, the G2 phase RED, and the stages of mitosis ORANGE. Color the arrows indicating all of the interphases in GREEN. Color the part of the arrow indicating mitosis PURPLE and the part of the arrow indicating cytokinesis YELLOW. M-PHASE YELLOW: GREEN: CYTOKINESIS INTERPHASE PURPLE: TELOPHASE MITOSIS ANAPHASE ORANGE METAPHASE BLUE: G1: GROWS PROPHASE PURPLE MITOSIS RED:G2: PREPARES GREEN: FOR MITOSIS INTERPHASE YELLOW: S PHASE: DNA REPLICATION GREEN: INTERPHASE Use the diagram and your notes to answer the following questions. 1. What is a series of events that cells go through as they grow and divide? CELL CYCLE 2. What is the longest stage of the cell cycle called? INTERPHASE 3. During what stage does the G1, S, and G2 phases happen? INTERPHASE 4. During what phase of the cell cycle does mitosis and cytokinesis occur? M-PHASE 5. During what phase of the cell cycle does cell division occur? MITOSIS 6. During what phase of the cell cycle is DNA replicated? S-PHASE 7. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell grow? G1,G2 8. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell prepare for mitosis? G2 9. How many stages are there in mitosis? 4 10. Put the following stages of mitosis in order: anaphase, prophase, metaphase, and telophase.