The Writ of Prohibition in New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADMINISTRATIVE LAW PAPER CODE- 801 TOPIC- WRITS Constitutional Philosophy of Writs

CLASS- B.A.LL.B VIIIth SEMESTER SUBJECT- ADMINISTRATIVE LAW PAPER CODE- 801 TOPIC- WRITS Constitutional philosophy of Writs: A person whose right is infringed by an arbitrary administrative action may approach the Court for appropriate remedy. The Constitution of India, under Articles 32 and 226 confers writ jurisdiction on Supreme Court and High Courts, respectively for enforcement/protection of fundamental rights of an Individual. Writ is an instrument or order of the Court by which the Court (Supreme Court or High Courts) directs an Individual or official or an authority to do an act or abstain from doing an act. Understanding of Article 32 Article 32 is the right to constitutional remedies enshrined under Part III of the constitution. Right to constitutional remedies was considered as a heart and soul of the constitution by Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar. Article 32 makes the Supreme court as a protector and guarantor of the Fundamental rights. Article 32(1) states that if any fundamental rights guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution is violated by the government then the person has right to move the Supreme Court for the enforcement of his fundamental rights. Article 32(2) gives power to the Supreme court to issue writs, orders or direction. It states that the Supreme court can issue 5 types of writs habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto, and certiorari, for the enforcement of any fundamental rights given under Part III of the constitution. The Power to issue writs is the original jurisdiction of the court. Article 32(3) states that parliament by law can empower any of courts within the local jurisdiction of India to issue writs, order or directions guaranteed under Article 32(2). -

G:\OSG\Desktop

No. 08-267 In the Supreme Court of the United States UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, PETITIONER v. JACOB DENEDO ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ARMED FORCES PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI GREGORY G. GARRE Acting Solicitor General LOUIS J. PULEO Counsel of Record Col., USMC MATTHEW W. FRIEDRICH Director Acting Assistant Attorney BRIAN K. KELLER General Deputy Director MICHAEL R. DREEBEN Deputy Solicitor General TIMOTHY H. DELGADO Lt., JAGC, USN ERIC D. MILLER Navy-Marine Corps Assistant to the Solicitor Appellate Government General Division JOHN F. DE PUE Department of the Navy Attorney Washington, D.C. 20374 Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether an Article I military appellate court has ju- risdiction to entertain a petition for a writ of error co- ram nobis filed by a former service member to review a court-martial conviction that has become final under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, 10 U.S.C. 801 et seq. (I) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Opinions below........................................ 1 Jurisdiction........................................... 1 Statutes involved...................................... 2 Statement............................................ 2 Reasons for granting the petition........................ 8 A. Collateral review of a final court-martial judgment is not “in aid of” the jurisdiction of a military appellate court.................................. 10 B. Coram nobis review is neither necessary nor appropriate in light of the alternative remedies available to former members of the armed forces.... 17 C. The question presented is important and warrants this Court’s review .............................. 21 Conclusion .......................................... 25 Appendix A — Court of appeals opinion (Mar. -

15. Judicial Review

15. Judicial Review Contents Summary 413 A common law principle 414 Judicial review in Australia 416 Protections from statutory encroachment 417 Australian Constitution 417 Principle of legality 420 International law 422 Bills of rights 422 Justifications for limits on judicial review 422 Laws that restrict access to the courts 423 Migration Act 1958 (Cth) 423 General corporate regulation 426 Taxation 427 Other issues 427 Conclusion 428 Summary 15.1 Access to the courts to challenge administrative action is an important common law right. Judicial review of administrative action is about setting the boundaries of government power.1 It is about ensuring government officials obey the law and act within their prescribed powers.2 15.2 This chapter discusses access to the courts to challenge administrative action or decision making.3 It is about judicial review, rather than merits review by administrators or tribunals. It does not focus on judicial review of primary legislation 1 ‘The position and constitution of the judicature could not be considered accidental to the institution of federalism: for upon the judicature rested the ultimate responsibility for the maintenance and enforcement of the boundaries within which government power might be exercised and upon that the whole system was constructed’: R v Kirby; Ex parte Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1956) 94 CLR 254, 276 (Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Fullagar and Kitto JJ). 2 ‘The reservation to this Court by the Constitution of the jurisdiction in all matters in which the named constitutional writs or an injunction are sought against an officer of the Commonwealth is a means of assuring to all people affected that officers of the Commonwealth obey the law and neither exceed nor neglect any jurisdiction which the law confers on them’: Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth (2003) 211 CLR 476, [104] (Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ). -

Common Law Powers

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. • ;:, . '. .',,~. ' b. '. ()" '. }" " Common Law Powers This microfiche was produced from documents received for inc~usion In the HeJIRS data base.' Since HCJRS cannot exercise of State Attornys control over the physical condition of the documents submitted, neral th~ individual frame qualit~ will vary. Th! resolution chart on this frame may be used to evaluate the :document quality. January, 1975 . ..~ Ij II . II 2 5 i, 1.0 1111/ . i.! 'I The National Association of Attorneys General 2.2 , ! ,! Committee on the Office of Attorney General I 1.1 :I , j A. F. Summer, Chairman I ·1 I .1l 1111,1.25 111111.4 1111I i.6 1 I I 1 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART . It NATIONAL BUREAU Of STANDARDS-1963-A I : I ; ! U Microfilmin& procedlfJres used to create this fiche comply with the standards set forth in 41CFR 101·11.504/. ~. ft. " • .1 Points of view or opinions $tahd in this documant are those of the authorls) and do not represent the official pOSition 9J policies o~ tha U.S. Department of Justice. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE lAW ENFORCEMENT ASSISTANCE ADMINISTRATION NA TlOHAl CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFERENCE SERVICE WASHINGTON, D.C. 20531 ··----w_~w ....... o ate f i I m'e II; 8/5/7 5 ~"""""'-~"'-~-' ~ .... ---.--~ --------------------- ----.--~-------------------------------------------- THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ATTORNEYS GENERAL National Association of Attorneys General COMMITTEE D.N THE OFFICE OF ATTORNEY GENERAL Committee on the Office of Attorney General I Chairman j Attorney General A. F. Summer, Mississippi President-Elect, National Association of Attorneys General ,\! Vice-Chairman Attorney General Rufus L. -

Functus Officio and the Piwrogative Writ of Prohibition

FUNCTUS OFFICIO AND THE PIWROGATIVE WRIT OF PROHIBITION By Ross A. SUNDBERG* An imaginary system cunningly planned for the evil purpose of thwarting justice and maximizing fruitless litigation would copy the major features of the extraordinary remedies. For the purpose of creating treacherous procedural snares and preventing or delaying the decision of cases on their merits, such a scheme would insist upon a plurality of remedies . .l There would appear to have been a deal of unnecessary litigation occasioned by the very fine line separating the stages at which the writs of certiorari and prohibition are properly sought. The objection in point of plurality of remedies is supported by the law of functus oficio-that despite the many points of law common to certiorari and prohibition each is available at a different stage in proceedings. The scene for the discussion that follows can be set very simply: Once proceedings have begun in the tribunal, but not until they have begun, prohibition may be obtained at any time until they are finished. if the proceedings have ended, the lower tribunal is said to be functus officio and prohibition ceases to be available.2 Is this a rehement that should be retained? Is it likely to result in many cases failing to reach the merits? Have the courts done anything to minimize the procedural difficulties that could arise from the distinction? These are some of the questions to which attention should be directed. The writs have the following points in common: historically they were used to control inferior courts; they are available in respect of a body with power to determine questions affecting the rights of subjects and having an obligation to act judicially; neither goes to an administrative tribunal, or so it is said;3 they are available only when the power to determine is de- rived from statute or subordinate legislation; the rules as to standing are the same; neither writ lies against the Crown. -

Petition for Writ of Prohibition/Mandate

RICHARD L. DUQUETTE Attorney at Law P.O. Box 2446 Carlsbad, CA 920182446 SBN 108342 Telephone: (760) 7300500 Attorney for Petitioner CHRISTINA HARRIS SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO, CENTRAL DIVISION CHRISTINA HARRIS and all ) CASE NO. UNNAMED AND FUTURE ) PETITIONERS SIMILARLY ) PETITION FOR WRIT OF SITUATED, ) PROHIBITION/MANDATE; ) STAY REQUESTED; Petitioner, ) VERIFICATION; MEMORANDUM ) OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES; VS. ) REQUEST FOR ATTORNEY FEES ) & COSTS; AND EXHIBITS SUPERIOR COURT OF SAN DIEGO ) COUNTY, And DOES 110; ) IMMEDIATE STAY OF 12/4/06 ) JURY TRIAL REQUESTED Respondent, ) ) (Local Rule 7.2.3) ______________________________ ) Word Count: 3,336 PETITION FOR WRIT OF PROHIBITION/MANDATE Immediate Action Requested TO THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA FOR THE COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO, HONORABLE J. SAMMARTINO, PRESIDING JUDGE: Petitioner lawfully authorized her counsel to appear for her in a misdemeanor matter pursuant to Penal Code sections 977 and 1043, and thus was not personally in court on September 8, 2006 (readiness hearing before Judge Mills) or November 8, 2006 -1- _______________________________________________________________________________________________ PETITION FOR WRIT OF PROHIBITION/MANDATE AND REQUEST FOR STAY (trial call before Judge Kirkman) (Exhibit B). The trial court called petitioner’s case, and since petitioner was not personally present, the court issued a warrant for her arrest, but stayed it until December 4, 2006. When the court was thereafter informed that petitioner was lawfully appearing: 1.) through counsel 2.) was never ordered in open court on the recordto appear at the readiness conference contrary to the court docket (Exhibit P), and thus had 3.) not failed to appear, the court refused to send the case out for a speedy Jury Trial. -

Mandamus in the Federal Courts As an Original Action

Volume 72 Issue 3 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 72, 1967-1968 3-1-1968 Mandamus in the Federal Courts as an Original Action Timothy L. McNickle Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Timothy L. McNickle, Mandamus in the Federal Courts as an Original Action, 72 DICK. L. REV. 468 (1968). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol72/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANDAMUS IN THE FEDERAL COURTS AS AN ORIGINAL ACTION In Stern v. South Chester Tube Co.1 the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held that, notwithstanding diver- sity, the federal district courts have no jurisdiction to grant relief in the nature of mandamus to compel inspection of the records of a private corporation when it is the only relief sought. A Pennsyl- vania statute2 which gives a stockholder of a corporation the right to inspect the corporation's books and records and which is enforce- able in Pennsylvania courts by a writ of mandamus 3 does not alter the limitation on the district court's jurisdiction as imposed by the All Writs Act.4 Contrary views of the district court's jurisdiction were ad- vanced by the majority and dissenting opinions in Stern. The majority could find no basis for mandamus jurisdiction in federal district courts. -

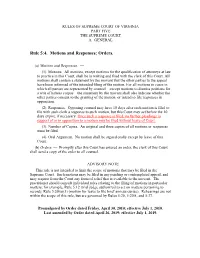

Rule 5:4. Motions and Responses; Orders

RULES OF SUPREME COURT OF VIRGINIA PART FIVE THE SUPREME COURT A. GENERAL Rule 5:4. Motions and Responses; Orders. (a) Motions and Responses. — (1) Motions. All motions, except motions for the qualification of attorneys at law to practice in this Court, shall be in writing and filed with the clerk of this Court. All motions shall contain a statement by the movant that the other parties to the appeal have been informed of the intended filing of the motion. For all motions in cases in which all parties are represented by counsel – except motions to dismiss petitions for a writ of habeas corpus – the statement by the movant shall also indicate whether the other parties consent to the granting of the motion, or intend to file responses in opposition. (2) Responses. Opposing counsel may have 10 days after such motion is filed to file with such clerk a response to such motion, but this Court may act before the 10 days expire, if necessary. Once such a response is filed, no further pleadings in support of or in opposition to a motion may be filed without leave of Court. (3) Number of Copies. An original and three copies of all motions or responses must be filed. (4) Oral Argument. No motion shall be argued orally except by leave of this Court. (b) Orders. — Promptly after this Court has entered an order, the clerk of this Court shall send a copy of the order to all counsel. ADVISORY NOTE This rule is not intended to limit the scope of motions that may be filed in the Supreme Court. -

RULES Supreme Court of the United States

RULES OF THE Supreme Court of the United States ADOPTED APRIL 18, 2019 EFFECTIVE JULY 1, 2019 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES 1 First Street, N. E. Washington, DC 20543 Clerk of the Court ............................... (202) 479-3011 Reporter of Decisions.......................... (202) 479-3390 Marshal of the Court........................... (202) 479-3333 Librarian................................................ (202) 479-3175 Telephone Operator ............................. (202) 479-3000 Visit the U.S. Supreme Court Website http://www.supremecourt.gov Mailing Address of the Solicitor General of the United States (see Rule 29.4) Room 5616 Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, N. W. Washington, DC 20530-0001 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I. THE COURT Page Rule 1. Clerk ................................................................................................ 1 Rule 2. Library ............................................................................................ 1 Rule 3. Term ................................................................................................ 1 Rule 4. Sessions and Quorum ................................................................... 2 PART II. ATTORNEYS AND COUNSELORS Rule 5. Admission to the Bar.................................................................... 2 Rule 6. Argument Pro Hac Vice.............................................................. 3 Rule 7. Prohibition Against Practice ...................................................... 4 Rule 8. Disbarment and Disciplinary -

Changed the Maxpages

0001 XPP 7.3C.1 Patch #3 SPEC: SC_01444: nonLLP: 1446: XPP-PROD Mon Oct 23 17:03:04 2006 [ST: 1] [ED: 10000] [REL: 2007] (Beg Group) VER: [SC_01444-Local:23 Oct 06 17:02][MX-SECNDARY: 03 Oct 06 14:42][TT-TT000001: 30 Aug 06 13:14] 0 Chapter 11 ACTIONS IN LIEU OF PREROGATIVE WRITS Synopsis PART I: STRATEGY § 11.01 Scope § 11.02 Objective and Strategy PART II: DETERMINING WHETHER ACTION IN LIEU OF PREROGATIVE WRITS MAY BE BROUGHT § 11.03 CHECKLIST: Determining Whether Action in Lieu of Prerogative Writs May Be Brought § 11.04 Understanding Nature and Purpose of Action in Lieu of Prerogative Writs [1] Understanding that Availability of Action in Lieu of Prerogative Writs Is Limited to that of Traditional Prerogative Writs [2] Maintaining Action in Lieu of Prerogative Writs as of Right § 11.05 Determining Whether Review of Official Action Could Have Been Sought by Applying for Writ of Certiorari [1] Determining Whether Review of Agency or Municipal Action is Sought [2] Determining Whether Adequate Remedy at Law Exists [3] Considering that Certiorari Review of Actions by Judicially-Created Agencies Is Unavailable § 11.06 Determining Whether Writ of Mandamus Was Available to Compel Official Action Sought 11-1 0002 XPP 7.3C.1 Patch #3 SPEC: SC_01444: nonLLP: 1446: XPP-PROD Mon Oct 23 17:03:05 2006 [ST: 1] [ED: 10000] [REL: 2007] VER: [SC_01444-Local:23 Oct 06 17:02][MX-SECNDARY: 03 Oct 06 14:42][TT-TT000001: 30 Aug 06 13:14] 0 NEW JERSEY PLEADINGS 11-2 [1] Determining Whether Compelling Official Action Is Remedy Sought [2] Considering that Mandamus -

Advance Sheets Supreme Court

376 N.C.—No. 3 Pages 558-679 BOARD OF LAW EXAMINERS ADVANCE SHEETS OF CASES ARGUED AND DETERMINED IN THE SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA APRIL 12, 2021 MAILING ADDRESS: The Judicial Department P. O. Box 2170, Raleigh, N. C. 27602-2170 COMMERCIAL PRINTING COMPANY PRINTERS TO THE SUPREME COURT AND THE COURT OF APPEALS THE SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA Chief Justice CHERI BEASLEY1 PAUL MARTIN NEWBY2 Associate Justices ROBIN E. HUDSON MARK A. DAVIS3 SAMUEL J. ERVIN, IV PHIL BERGER, JR.4 MICHAEL R. MORGAN TAMARA PATTERSON BARRINGER5 ANITA EARLS Former Chief Justices RHODA B. BILLINGS JAMES G. EXUM, JR. BURLEY B. MITCHELL, JR. HENRY E. FRYE SARAH PARKER MARK D. MARTIN Former Justices ROBERT R. BROWNING GEORGE L. WAINWRIGHT, JR. J. PHIL CARLTON EDWARD THOMAS BRADY WILLIS P. WHICHARD PATRICIA TIMMONS-GOODSON JAMES A. WYNN, JR. ROBERT N. HUNTER, JR. FRANKLIN E. FREEMAN, JR. ROBERT H. EDMUNDS, JR. G. K. BUTTERFIELD, JR. BARBARA A. JACKSON ROBERT F. ORR Clerk AMY L. FUNDERBURK Librarian THOMAS P. DAVIS Marshal WILLIAM BOWMAN 1Term ended 31 December 2020. 2Sworn in 1 January 2021. 3Term ended 31 December 2020. 4Sworn in 1 January 2021. 5Sworn in 1 January 2021. i ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE OF THE COURTS Director MCKINLEY WOOTEN6 ANDREW HEatH7 Assistant Director DAVID F. HOKE OFFICE OF APPELLATE DIVISION REPORTER ALYSSA M. CHEN JENNIFER C. PETERSON NICCOLLE C. HERNANDEZ 6Resigned 7 January 2021. 7Appointed 8 January 2021. ii SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA CASES REPORTED FILED 5 FEBRUARY 2021 Comm. to Elect Dan Forest In re J.T.C. ...................... 642 v. -

State Ex Rel. New Prospect V. Ruehlman

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS FIRST APPELLATE DISTRICT OF OHIO HAMILTON COUNTY, OHIO STATE OF OHIO EX REL. NEW : CASE NO. C-180591 PROSPECT BAPTIST CHURCH, : Relator, O P I N I O N. : vs. : HON. ROBERT P. RUEHLMAN, JUDGE, COURT OF COMMON : PLEAS, HAMILTON COUNTY, OHIO, Respondent. : Original Action in Mandamus and Prohibition Judgment of the Court: Writ of Mandamus is Denied; Writ of Prohibition is Granted in Part and Denied in Part Date of Judgment Entry: December 20, 2019 American Civil Liberties Union of Ohio Foundation, Joseph W. Mead, Freda J. Levinson and David J. Carey, for Relator, Joseph T. Deters, Hamilton County Prosecuting Attorney, Pamela J. Sears and Cooper D. Bowen, Assistant Prosecuting Attorneys, for Respondent. OHIO FIRST DISTRICT COURT OF APPEALS MOCK, Presiding Judge. {¶1} This is an original action in which the relator, New Prospect Baptist Church (“New Prospect”), a local religious organization, seeks writs of prohibition and mandamus involving respondent, the Hon. Robert P. Ruehlman, a judge of the Hamilton County Court of Common Pleas. {¶2} New Prospect seeks to prevent respondent from enforcing an August 16, 2018 permanent injunction issued under Civ.R. 65, in a nuisance action brought against the city of Cincinnati in the case numbered A-1804285 (“the underlying case”). Based on affidavits from public health and police officials, respondent found that illegal encampments by homeless persons on public rights-of-way on Third Street in downtown Cincinnati were a nuisance and constituted “a hazard to the health and safety of the general public, including those living in the illegal encampments.” {¶3} Respondent further found that, in response to its earlier temporary restraining orders, the homeless encampments were moving to other locations within the Cincinnati city limits including a community park in the city’s Over-the- Rhine neighborhood.