A Comparative Analysis of the Black Arts Movement and the Hip Hop Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

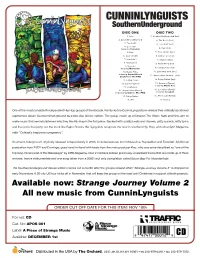

Strange Journey Volume 2 All New Music from Cunninlynguists

DISC ONE DISC TWO 1. Intro 1. SouthernUnderground (Inst) 2. SouthernUnderground 2. The South (Inst) 3. The South 3. Love Ain't (Inst) 4. Love Ain't 4. Rain (Inst) featuring Tonedeff 5. Rain 5. Doin’ Alright (Inst) 6. Doin’ Alright 6. Old School (Inst) 7. Interlude 1 7. Seasons (Inst) 8. Old School 8. Nasty Filthy (Inst) 9. Seasons 9. Falling Down (Inst) featuring Masta Ace 10. Nasty Filthy 10. Sunrise/Sunset (Inst) featuring Supastition & 11. Appreciation (Remix) - (Inst) Cashmere The PRO 11. Falling Down 12. Dying Nation (Inst) 12. Sunrise/Sunset 13. Seasons (Remix) featuring Masta Ace 13. Interlude 2 14. Appreciation (Remix) 14. Love Ain't (Remix) featuring featuring Cashmere The PRO Tonedeff 15. Dying Nation 15. The South (Remix) 16. War 16. Karma One of the most consistent independent Hip Hop groups of the decade, Kentucky trio CunninLynguists re-release their critically acclaimed sophomore album SouthernUnderground as a two disc deluxe edition. The group, made up of Deacon The Villain, Natti and Kno, aim to make music that reminds listeners why they like Hip Hop in the first place. Backed with quality beats and rhymes, gritty sounds, witty lyrics and low ends that jump out the trunk like Rajon Rondo, the ‘Lynguists recapture the soul in southern Hip Hop, with what Spin Magazine calls “Outkast’s tragicomic poignancy”. SouthernUnderground, originally released independently in 2003, includes features from Masta Ace, Supastition and Tonedeff. Additional production from RJD2 and Domingo, goes hand-in-hand with beats from the main producer Kno, who was once described as “one of the top loop-miners east of the Mississippi” by URB Magazine. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies Undergraduate & Graduate Course Descriptions

W.E.B. DU BOIS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES UNDERGRADUATE & GRADUATE COURSE DESCRIPTIONS UNDERGRADUATE AFROAM 101. Introduction to Black Studies Interdisciplinary introduction to the basic concepts and literature in the disciplines covered by Black Studies. Includes history, the social sciences, and humanities as well as conceptual frameworks for investigation and analysis of Black history and culture. AFROAM 111. Survey African Art Major traditions in African art from prehistoric times to present. Allied disciplines of history and archaeology used to recover the early history of certain art cultures. The aesthetics in African art and the contributions they have made to the development of world art in modern times. (Gen.Ed. AT, G) AFROAM 113. African Diaspora Arts Visual expression in the Black Diaspora (United States, Caribbean, and Latin America) from the early slave era to the present. AFROAM 117. Survey of Afro-American Literature (4 credits) The major figures and themes in Afro-American literature, analyzing specific works in detail and surveying the early history of Afro-American literature. What the slave narratives, poetry, short stories, novels, drama, and folklore of the period reveal about the social, economic, psychological, and artistic lives of the writers and their characters, both male and female. Explores the conventions of each of these genres in the period under discussion to better understand the relation of the material to the dominant traditions of the time and the writers' particular contributions to their own art. (Gen.Ed. AL, U) (Planned for Fall) AFROAM 118. Survey of Afro-American Literature II (4 credits) Introductory level survey of Afro-American literature from the Harlem Renaissance to the present, including DuBois, Hughes, Hurston, Wright, Ellison, Baldwin, Walker, Morrison, Baraka and Lorde. -

San Diego Public Library New Additions September 2008

San Diego Public Library New Additions September 2008 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes Newspaper Room Audiovisual Materials Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/ABE Abé, Shana. The dream thief FIC/ABRAHAMS Abrahams, Peter, 1947- Delusion [SCI-FI] FIC/ADAMS Adams, Douglas, 1952- Dirk Gently's holistic detective agency FIC/ADAMSON Adamson, Gil, 1961- The outlander : a novel FIC/ADLER Adler, Elizabeth (Elizabeth A.) Meet me in Venice FIC/AHERN Ahern, Cecelia, 1981- There's no place like here FIC/ALAM Alam, Saher, 1973- The groom to have been FIC/ALEXANDER Alexander, Robert, 1952- The Romanov bride FIC/ALI Ali, Tariq. Shadows of the pomegranate tree FIC/ALLEN Allen, Preston L., 1964- All or nothing [SCI-FI] FIC/ALLSTON Allston, Aaron. Star wars : legacy of the force : betrayal [SCI-FI] FIC/ANDERSON Anderson, Kevin J. Darksaber FIC/ARCHER Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- A prisoner of birth FIC/ARCHER Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- A prisoner of birth FIC/ARCHER Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- Cat o'nine tales and other stories FIC/ASARO Asaro, Catherine. The night bird FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Emma FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Mansfield Park FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Minor works FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Northanger Abbey and Persuasion FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Sense and sensibility FIC/BAHAL Bahal, Aniruddha, 1967- Bunker 13 FIC/BALDACCI Baldacci, David. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

Evan Dando Fireside Mauro Scocco Jesse Malin Libertines

Nummer 2 • 2003 Sveriges största musiktidning Evan Dando Fireside Mauro Scocco Jesse Malin Libertines TheCardigans Appliance • The Radio Dept. • Luna • All Systems Go BLÅGULT GULD: Anders Ilar • Chords • Natalie Gardiner • Pauline Kamusewu • Dialog Cet Groove 2 • 2003 Ledare Omslag Nick Cave av Polly Borland Byt ut politikerna! Groove Box 112 91 Tre frågor till Björn Olsson sidan 4 404 26 Göteborg En idé som kanske inte är så radikal nister Thomas Öberg och Stefan The Radio Dept. sidan 4 som man vid en första anblick kan Sundström jordbruksminister. Telefon 031–833 855 tro vore att göra musiker och andra Marit Bergman miljöminister, Dre- En överklass i nitar sidan 4 Elpost [email protected] kulturarbetare till politiker – för en gen näringsminister, utrikesminis- http://www.groove.st Appliance sidan 6 roligare och mer mänsklig framtid. ter ska Hives-Pelle vara, Promoe Vi skulle utrota hyckleriet kring justitieminister, Thomas diLeva Vad är det för fel på folk? sidan 6 Chefredaktör & ansvarig utgivare sprit och festande hos våra folkval- försvarsminister och som statsmi- Gary Andersson, [email protected] Luna sidan 8 da och därmed inse att samhällets nister kunde Robyn passa. Titta på toppar faktiskt också bara är män- denna lista och säg mig ärligt att Skivredaktör Ett subjektivt alfabet sidan 8 niskor. Dessutom skulle vi styra in detta skulle funka sämre än upp- Björn Magnusson, [email protected] på en mer humanistisk syn som ställningen för vår tandlösa och Blågult guld sidan 10 inriktar sig mer på livskvalitet än på räddhågsna ledning. Nej, jag tänk- Mediaredaktör Dan Andersson, [email protected] Evan Dando sidan 12 sterila ekonomiska kalkyler. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

2010 Harlem Book Fair Program & Schedule

2010 HARLEM BOOK FAIR PROGRAM & SCHEDULE Tribute to Book-TV Presented by Max Rodriguez, Founder – Harlem Book Fair Schomburg/Hughes Auditorium 11:00a - 11:15a Tribute to Howard Dodson, Chief of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Presented by Herb Boyd; Max Rodriguez; Kassahun Checole Schomburg/Hughes Auditorium 11:15a - 11:30a SCHOMBURG C-SPAN PANEL DISCUSSIONS God Is Not A Christian: Can We All Get Along in A World of Holy Wars and Religious Chauvinism? Schomburg/Hughes Auditorium (Televised Live on C-Span’s Book-TV) 11:40a - 12:55p Who is the one true God? Who are the chosen people? Questions like these have driven a thousand human struggles through war, terrorism and oppression. Humanity has responded by branching off into multiple religions--each one pitted against the other. But it doesn't have to be that way, according to Bishop Carlton Pearson and many others. This New Thought spiritual leader will discuss these and many other burning questions with author and theologian, Obery Hendricks and others. MODERATOR: Malaika Adero, Up South: Stories, Studies, and Letters of This Century's African American Migrations, The New Press PANELISTS: Obrey Hendricks, The Politics of Jesus: Rediscovering the True Revolutionary Nature of Jesus' Teachings and How They Have Been Corrupted (Doubleday); Bishop Carlton Pearson, God is Not a Christian, Nor a Jew, Muslim, Hindu...God Dwells with Us, in Us, Around Us, as Us (Simon&Schuster), Sarah Sayeed,, and others. Book signing immediately following discussion in Schomburg lobby. Is Racial Justice Passe? Barack Obama, American Society, and Human Rights in the 21st Century Schomburg/Hughes Auditorium (Televised Live on C-Span’s Book-TV) 1:05p - 2:20p Barack Obama's election as the 44th President of the United States upends conventional notions of citizenship, racial justice, and equality that contoured the modern civil rights movement. -

Fear of a Muslim Planet

SOUND UNBOUND edited by Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 6 2008 Paul D. Miller All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any elec- tronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information stor- age and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. For information about special quantity discounts, please email special_sales@mitpress .mit.edu This book was set in Minion and Syntax on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong, and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sound unbound / edited by Paul D. Miller. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-63363-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Music—21st century—History and criticism. 2. Music and technology. 3. Popular culture—21st century. I. DJ Spooky That Subliminal Kid. ML197.S694 2008 780.9005—dc22 2007032443 10987654321 Contents Foreword by Cory Doctorow ix 1 An Introduction, or My (Ambiguous) Life with Technology 1 Steve Reich 2 In Through the Out Door: Sampling and the Creative Act 5 Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid 3 The Future of Language 21 Saul Williams 4 The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagiarism Mosaic 25 Jonathan Lethem 5 ‘‘Roots and Wires’’ Remix: Polyrhythmic Tricks and the Black Electronic 53 Erik Davis 6 The Life and Death of Media 73 Bruce Sterling 7 Un-imagining Utopia 83 Dick Hebdige 8 Freaking the Machine: A Discussion about Keith Obadike’s Sexmachines 91 Keith + Mendi Obadike 9 Freeze Frame: Audio, Aesthetics, Sampling, and Contemporary Multimedia 97 Ken Jordan and Paul D. -

A Moral Call for a National Moratorium on Water, Power and Broadband Shutoffs

To: The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Mitch McConnell Speaker Majority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. Senate Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable Kevin McCarthy The Honorable Chuck Schumer Minority Leader Democratic Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. Senate Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20510 cc: U.S. Senate Environment and Public Works Committee U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation Date: July 30, 2020 A Moral Call for a National Moratorium on Water, Power and Broadband Shutoffs Dear Senate Majority Leader McConnell, Minority Leader Schumer, Speaker Pelosi, Minority Leader McCarthy, Chairman Barrasso, and Ranking Member Carper, Chairwoman Murkowski, Ranking Member Manchin, Chairman Wicker, and Ranking Member Cantwell: On behalf of our congregants, members and supporters nationwide, we, the undersigned 537 faith leaders and organizations urge Congress to take decisive, moral action and implement a nationwide moratorium on the shut-offs of electricity, water, broadband, and all other essential utility services for all households, places of worship, and other non-profit community centers as part of the next COVID-19 rescue package. As faith leaders in the Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Baha’i, and other religious traditions, we call on you to come to the aid of struggling families and houses of worship across the country--and ensure that we all have access to water, power, and broadband during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Nearly 80% of the American population self identifies as being grounded in a faith ideology. -

CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY AWH Department

DRAFT – DO NOT DISTRIBUTE CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY AWH Department Course Syllabus AWS 600—Seminar in Africana Women’s Studies: Sonia Sanchez Instructor: Dr. Stephanie Y. Evans Office Hours Wednesdays, 3:00pm-4:00 pm or by appointment Office Location McPheeters-Dennis Hall, Room 200w Office Telephone 404-880-6352 Email [email protected] Resource Page: www.ProfessorEvans.net Course# and Credit Level Course Title Semester Time Section Hours (U/G) CAWS 01 Seminar in Africana Women’s Studies 3 Spring 2015 Thursday G 600 CMW 314 4:30-7:00 pm Brief Description This course is designed to introduce students to the discipline of Africana Women’s Studies by providing an overview of the social, political, intellectual and theoretical approaches utilized in such an academic undertaking. Special focus will be given to AWS via close reading of Professor Sonia Sanchez’s body of work. Sonia Sanchez on Womanism “I wrote poems that were obviously womanist before we even started talking about it.” (p. 73) “I think that one of the things that we, that black women, have to understand is that they’ve been involved in womanist issues all their lives.” (p. 103) “So, what I’m saying is at some point our sensibilities, our sensitivity, our herstory made us approach the whole idea of what it was to be a black woman in a different fashion, in a different sense. And that is why I think Alice talks about being a womanist, as opposed to a feminist.” (p. 104) “I think you—if you say out loud, I am a womanist or I want to go into women’s studies and/or I want to go to a university to learn something and I’m a history major or a political science major, the very fact that you are a black woman coming into those departments will change some of the stuff that goes on in there, by the very fact that you are there.” (p.