Loggerhead-Shrike-En.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

True Shrikes), Including 31 Specieswithin Genera Are Coveredin Singlepage Overviews.Line Lanius, Coruinella and Eurocephalus

Books SHRIKES. Norbert Lefranc. 1997. Yale University Some species have bright rufous or sandy caps Press, New Haven, Connecticut. Hard cover, 192 and backs. A few, such as the Long-tailedShrike, pp. $35.00 U.S. have strikinggeographic plumage variations. Some shrikesare as small as House Sparrows. The recentflood of world-wideidentification guides for specific groups of birds, such as seabirds, In 35 pages of introductorymaterial, the author waterfowl and shorebirds, has now reached presents informationon: taxonomy,overviews of passerine groupings, and the treatment has the genera, and a brief guide to the features of the expanded to include life history information.This species accounts. The overview of the genus is a welcome addition, as many bird enthusiasts Laniuscovers: names; morphology,plumages and have expanded their interests, and wish to learn molts; origins, present distribution,migration 'and more about the birds they see. Many of these wintering areas; habitat; social organization and guides are being written in Europe and cover general behavior;food habits,larders and foraging groupswhich occur primarilyin the Old World. behavior; nests, eggs and breeding behavior; population dynamics; population changes and Shrikes covers the three genera of the family presumedcauses; and conservation.The othertwo Laniidae(true shrikes), including 31 specieswithin genera are coveredin singlepage overviews.Line Lanius, Coruinella and Eurocephalus. Twenty- drawings in the introduction supplerbent the color sevenof thesespecies are in the firstgenus, whose plates. name is the Latin word for butcher, perhaps referringto their habit of hangingprey on spines. Species accounts average three pages (range 1- 9), and include a clear range map (1/4 to 1 page), Scientistsbelieve that the family Laniidae evolved identification details, measurements, distribution in Australia as part of a great radiation that and status, molt, voice, habitat, habits, food, produced the corvids, a number of Australian breeding and references. -

Bird Species Checklist

6 7 8 1 COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi Bank Swallow R White-throated Sparrow R R R Bird Species Barn Swallow C C U O Vesper Sparrow O O Cliff Swallow R R R Savannah Sparrow C C U Song Sparrow C C C C Checklist Chickadees, Nuthataches, Wrens Lincoln’s Sparrow R U R Black-capped Chickadee C C C C Swamp Sparrow O O O Chestnut-backed Chickadee O O O Spotted Towhee C C C C Bushtit C C C C Black-headed Grosbeak C C R Red-breasted Nuthatch C C C C Lazuli Bunting C C R White-breasted Nuthatch U U U U Blackbirds, Meadowlarks, Orioles Brown Creeper U U U U Yellow-headed Blackbird R R O House Wren U U R Western Meadowlark R O R Pacific Wren R R R Bullock’s Oriole U U Marsh Wren R R R U Red-winged Blackbird C C U U Bewick’s Wren C C C C Brown-headed Cowbird C C O Kinglets, Thrushes, Brewer’s Blackbird R R R R Starlings, Waxwings Finches, Old World Sparrows Golden-crowned Kinglet R R R Evening Grosbeak R R R Ruby-crowned Kinglet U R U Common Yellowthroat House Finch C C C C Photo by Dan Pancamo, Wikimedia Commons Western Bluebird O O O Purple Finch U U O R Swainson’s Thrush U C U Red Crossbill O O O O Hermit Thrush R R To Coast Jackson Bottom is 6 Miles South of Exit 57. -

Field Checklist (PDF)

Surf Scoter Marbled Godwit OWLS (Strigidae) Common Raven White-winged Scoter Ruddy Turnstone Eastern Screech Owl CHICKADEES (Paridae) Common Goldeneye Red Knot Great Horned Owl Black-capped Chickadee Barrow’s Goldeneye Sanderling Snowy Owl Boreal Chickadee Bufflehead Semipalmated Sandpiper Northern Hawk-Owl Tufted Titmouse Hooded Merganser Western Sandpiper Barred Owl NUTHATCHES (Sittidae) Common Merganser Least Sandpiper Great Gray Owl Red-breasted Nuthatch Red-breasted Merganser White-rumped Sandpiper Long-eared Owl White-breasted Nuthatch Ruddy Duck Baird’s Sandpiper Short-eared Owl CREEPERS (Certhiidae) VULTURES (Cathartidae) Pectoral Sandpiper Northern Saw-Whet Owl Brown Creeper Turkey Vulture Purple Sandpiper NIGHTJARS (Caprimulgidae) WRENS (Troglodytidae) HAWKS & EAGLES (Accipitridae) Dunlin Common Nighthawk Carolina Wren Osprey Stilt Sandpiper Whip-poor-will House Wren Bald Eagle Buff-breasted Sandpiper SWIFTS (Apodidae) Winter Wren Northern Harrier Ruff Chimney Swift Marsh Wren Sharp-shinned Hawk Short-billed Dowitcher HUMMINGBIRDS (Trochilidae) THRUSHES (Muscicapidae) Cooper’s Hawk Wilson’s Snipe Ruby-throated Hummingbird Golden-crowned Kinglet Northern Goshawk American Woodcock KINGFISHERS (Alcedinidae) Ruby-crowned Kinglet Red-shouldered Hawk Wilson’s Phalarope Belted Kingfisher Blue-gray Gnatcatcher Broad-winged Hawk Red-necked Phalarope WOODPECKERS (Picidae) Eastern Bluebird Red-tailed Hawk Red Phalarope Red-headed Woodpecker Veery Rough-legged Hawk GULLS & TERNS (Laridae) Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Gray-cheeked Thrush Golden -

NORTHERN SHRIKE-TIT CRESTED SHRIKE-TIT Falcunculus (Frontatus) Whitei

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory NORTHERN SHRIKE-TIT CRESTED SHRIKE-TIT Falcunculus (frontatus) whitei Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Near Threatened Photo: T. Collins Description The northern shrike-tit is a distinctive medium-sized bird. It has a dull green back and wings, yellow belly and boldly marked black and white head, with a small black crest. Its bill is unusually deep, strong and hooked. Distribution This taxon forms part of a superspecies of three geographically isolated populations, in eastern and south-eastern Australia, south-western Australia and northern Australia. These taxa are variously accorded subspecific (Christidis and Boles 1994, 2008) or full specific (Schodde and Known locations of the northern shrike-tit Mason 1999) status. Molecular genetics analyses are required to resolve the taxonomy within the to near Borroloola. More recent records in the superspecies. Northern Territory (NT) expand our knowledge of them here and include locations in north east Until relatively recently there were remarkably Arnhem Land to Kalkarindgi (semi-arid Victoria few records of the northern shrike-tit (Robinson River District). The most frequent recent records and Woinarski 1992), scattered between the are from the Sturt Plateau and from the south-west Kimberley (Western Australia) east Maningrida area (R. Noske pers. comm.), though For more information visit www.denr.nt.gov.au 2 this reflects greater research effort in these Northern shrike-tits use calls to maintain pairs areas. and territories, particularly during the breeding season. These calls, though not loud, are The species has not been relocated in the distinctive and provide the best means of Borroloola area since it was first recorded there detecting the subspecies at a location (Ward in 1913. -

Small, D. M. 2017. Winter Site Fidelity and Over

Fall 2017 Maryland Birdlife Volume 66, Number 2 Maryland Birdlife 66(2):9–19 Winter Site Fidelity and Over-wintering Site Persistence of a Northern Shrike, Lanius borealis, in Maryland Daniel M. Small Chester River Field Research Station, Washington College, 210 South Cross Street, Chestertown, MD 21620 [email protected] Abstract: Observations were made of a single adult Northern Shrike (Lanius borealis) over a four-year period during the winters of 2007–2008 to 2011–2012 on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. A new record early arrival date of 13 October and a record late last occurrence date of 16 April were established for the state. Average annual residence time was 155 days ±13.9 SE. Average home range size was 71.7 ha ±23.1 SE (177.1 ac ±57.1 SE) using the minimum convex polygon method and 69.1 ha ±17.7 SE (170.5 ac ±43.7 SE ) using the kernel density estimate for 95% percent volume contours. Average core home range or 50% percent volume contours was 13.7 ha ±5.49 SE (33.9 ac ±13.6 SE). Each winter’s home range was comprised of multiple habitat types, but native grasslands and early successional shrub-scrub habitat annually dominated the core home range. Northern Shrikes (Lanius borealis) are Nearctic breeders that migrate to southern Canada and northern United States annually, but distance and timing vary greatly between individuals and across years (Paruk et al. 2017). Numbers of migrating Northern Shrikes fluctuate annually throughout the winter range (Atkinson 1995, Rimmer and Darmstadt 1996), and the species is not recorded annually in Maryland. -

Standard Abbreviations for Common Names of Birds M

Standard abbreviations for common names of birds M. Kathleen Klirnkiewicz I and Chandler $. I•obbins 2 During the past two decadesbanders have taken The system we proposefollows five simple rules their work more seriouslyand have begun record- for abbreviating: ing more and more informationregarding the birds they are banding. To facilitate orderly record- 1. If the commonname is a singleword, use the keeping,bird observatories(especially Manomet first four letters,e.g., Canvasback, CANV. and Point Reyes)have developedstandard record- 2. If the common name consistsof two words, use ing forms that are now available to banders.These the first two lettersof the firstword, followed by forms are convenientfor recordingbanding data the first two letters of the last word, e.g., manually, and they are designed to facilitate Common Loon, COLO. automateddata processing. 3. If the common name consists of three words Because errors in species codes are frequently (with or without hyphens),use the first letter of detectedduring editing of bandingschedules, the the first word, the first letter of the secondword, Bird BandingOffices feel that bandersshould use and the first two lettersof the third word, e.g., speciesnames or abbreviationsthereof rather than Pied-billed Grebe, PBGR. only the AOU or speciescode numbers on their field sheets.Thus, it is essentialthat any recording 4. If the common name consists of four words form have provision for either common names, (with or without hypens), use the first letter of Latin names, or a suitable abbreviation. Most each word, •.g., Great Black-backed Gull, recordingforms presentlyin use have a 4-digit GBBG. -

Äthiopien Im Februar 2012 Schulz & Gerdes

ALBATROS-TOURS ORNITHOLOGISCHE STUDIENREISEN Jürgen Schneider Altengassweg 13 - 64625 Bensheim - Tel.: +49 (0) 62 51 22 94 - Fax: +49 (0) 62 51 64 457 E-Mail: [email protected] - Homepage: www.albatros-tours.com Äthiopien vom 04.02.12 – 23.02.12 von M. Schulz & Dr. K. Gerdes Foto: J. Schneider Reisebericht 1 ALBATROS-TOURS Unsere Gruppe von link nach rechts: R.M.Schulz (Reiseleiter), R.E.Schulz, K.Gerdes, A.Freitag, H.Gerdes, A.Krüger, S.Grüttner und G.Peter Foto: M. Schulz Reisebericht 2 ALBATROS-TOURS Äthiopien vom 04.02.12 – 23.02.12 von M. Schulz Reiseleiter: M. Schulz Teilnehmer: E. Schulz, S. Grüttner, Dr. K. Gerdes, H. Gerdes, A. Krüger, A.Freitag, G. Peter Sa. 04.02.2012 Start in Frankfurt, alle sind da. So 05.02.2012 Ankunft in Addis. Lange Einreise Warterei .Es sind nur 2 Schalter besetzt aber 2 große Flugzeuge angekommen. Adane empfängt uns .Simone war schon vor 3 Jahren hier, hat also gute Erfahrungen mit Adane, dem Land und der Ornis. Wir fahren zum Hotel (mit 3 Autos) in dem Günther, der aus Kenia gekommen ist, auf uns wartet. Frisch machen umziehen und –START- zum Abenteuer Äthiopien. Erste Eindrücke werden gesammelt. Eine menschenvolle, von Autos und deren Abgasen/Staub total versmogte Stadt. Die ganze Stadt entspricht so gar nicht deutschem Standard. Alles auch „NEUES“ sieht irgendwie „Alt“ aus… Die „Neuheit“ bei dieser „Schneider Reise“ ist die Begleitung durch einen einheimischen Orni. Murat wird unterwegs eingeladen, ein Kenner der Vogelwelt und der Örtlichkeiten! Ein „vogelverrückter“, der ein SEHR kompetenter, angenehmer Reisebegleiter war. -

WINTER of the BUTCHER-BIRD: the Northern Shrike Invasion of 1995-1996

WINTER OF THE BUTCHER-BIRD: The Northern Shrike Invasion of 1995-1996 by Wayne R. Petersen and William E. Davis, Jr. Little did Massachusetts birders realize that the appearance of a Northern Shrike {Lanius excubitor) in East Orleans on October 13, 1995, was the beginning of perhaps the most spectacular winter irruption of Northern Shrikes ever in the Northeast. Although the vanguard of Northern Shrike migration does not usually arrive in Massachusetts until late October (Veit and Petersen 1993), the appearance of one shrike on October 13 was hardly reason to suspect that anything out of the ordinary was about to take place. To underscore the magnitude of the shrike invasion, consider the following; Between October 13, 1995 and April 27, 1996, a total of 192 Northern Shrike reports appeared in the Bird Sightings column of Bird Observer (Bird Observer24:51, 111, 170, 219, 227). • In describing the winter season in New England, Blair Nikula (1996) noted that Northern Shrikes appeared in "record or near-record numbers everywhere—far too many to tally accurately, but dozens were found in every state and the Regionwide total easily exceeded 300 birds." • Northern Shrike was one of only 17 species reported on every one of 24 eastern Massachusetts Christmas Bird Counts (CBCs) summarized in Bird Observer (24:117), and the 1995-1996 shrike count equaled or exceeded ten- year maxima in 27 of 29 CBC count areas (Table 1). • CBC Counts for Northern Shrikes included 25 at Nantucket and 19 each at Concord, Greater Boston, and Newburyport. • 561 Northern Shrikes were tallied on New England CBCs, with this species reported on all but five of 104 CBCs conducted throughout New England in 1995-1996; the average New England CBC total for Northern Shrike over the past 12 years is 62.9 birds (Petersen 1996). -

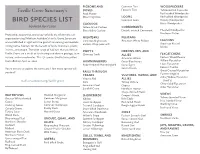

Bird Species List

PIGEONS AND Common Tern WOODPECKERS DOVES Forster’s Tern Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Faville Grove Sanctuary’s Rock Pigeon Red-headed Woodpecker Mourning Dove LOONS Red-bellied Woodpecker BIRD SPECIES LIST Common Loon Downy Woodpecker CUCKOOS Hairy Woodpecker Updated April 2020 Yellow-billed Cuckoo CORMORANTS Black-billed Cuckoo Double-crested Cormorant Pileated Woodpecker Protecting, supporting, and enjoying birds are what make our Northern Flicker organization sing! Madison Audubon’s Faville Grove Sanctuary NIGHTJARS PELICANS American White Pelican FALCONS was established in 1998 with the goal of conserving and reestab- Common Nighthawk Eastern Whip-poor-will American Kestrel lishing native habitats for the benefit of birds, mammals, plants, Merlin insects, and people. The wide range of habitats that you find at SWIFTS HERONS, IBIS, AND Faville Grove are a result of fascinating and diverse geology, burn Chimney Swift ALLIES FLYCATCHERS history, and microclimates. This 171-species bird list was pulled American Bittern Eastern Wood-Pewee from eBird on April 22, 2020. HUMMINGBIRDS Great Blue Heron Willow Flycatcher Ruby-throated Hummingbird Great Egret Least Flycatcher Eastern Phoebe You’re invited to explore the sanctuary. How many species will Green Heron Great Crested Flycatcher you find? RAILS THROUGH CRANES VULTURES, HAWKS, AND Eastern Kingbird Alder/Willow Flycatcher Virginia Rail ALLIES (Traill’s) madisonaudubon.org/faville-grove Sora Turkey Vulture Olive-sided Flycatcher American Coot Osprey Alder Flycatcher Sandhill Crane Northern -

Lanius Colluriocollurio)) Atat Gambell,Gambell, Alaskaalaska

FirstFirst NorthNorth AmericaAmerica RecordRecord ofof Red-backedRed-backed ShrikeShrike ((LaniusLanius colluriocollurio)) atat Gambell,Gambell, AlaskaAlaska PAUL E. LEHMAN • 11192 PORTOBELO DRIVE, SAN DIEGO, CA 92124 • LEHMAN.PAULVERIZON.NET PETER PYLE • THE INSTITUTE FOR BIRD POPULATIONS, P. O. BOX 1346, POINT REYES STATION, CA 94956 • PPYLEBIRDPOP.ORG NIAL MOORES • BIRDS KOREA, 1010, SAMIK TOWER 3DONG, NAMCHEON 2 DONG, BUSAN, REPUBLIC OF KOREA • NIAL.MOORESBIRDSKOREA.ORG JULIAN HOUGH • 80 SEA STREET, NEW HAVEN, CT 06519 • WWW.NATURESCAPEIMAGES.WORDPRESS.COM GARY H. ROSENBERG • P. O. BOX 91856, TUCSON, AZ 85752 • GHROSENBERGCOMCAST.NET Abstract and winters primarily in southern Africa. that provide exposed, rich soil, some degree We document the first record for Alaska and We speculate that it may have reached of protection from the wind, and (by late the Western Hemisphere of a Red-backed Gambell via misorientation in an approxi- summer and early autumn) a relatively lush Shrike (Lanius collurio), a first-fall bird pres- mately 180º opposite direction from normal growth of two species of Artemisia. Known ent at Gambell, St. Lawrence Island 3-22 migratory paths. A bird identified after an colloquially as wormwood or sage, this veg- October 2017. It was primarily in juvenile extensive review as a hybrid Red-backed × etation grows to a height of approximately a feathering but showed evidence that the Turkestan Shrike had occurred previously in half-meter or more. The food and cover pro- preformative body-feather molt had com- Mendocino County, California, in March–- vided by the middens are attractive to both menced. Based on details of structure and April 2015; but the Gambell shrike showed Asian and North American landbird migrants, plumage and following review of a series of no evidence of hybridization. -

Loggerhead Shrike Lanius Ludovicianus

Wyoming Species Account Loggerhead Shrike Lanius ludovicianus REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: Migratory Bird USFS R2: Sensitive USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: Sensitive State of Wyoming: Protected Bird CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: Bird of Conservation Concern WGFD: NSS4 (Bc), Tier II WYNDD: G4, S4S5 Wyoming Contribution: LOW IUCN: Least Concern PIF Continental Concern Score: 11 STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS The Wyoming Natural Diversity Database has assigned Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) a state conservation rank ranging from S4 (Apparently Secure) to S5 (Secure) because of uncertainty over extrinsic stressors and population trends of the species in Wyoming. Loggerhead Shrike is classified as Sensitive by Region 2 of the U.S. Forest Service and the Wyoming Bureau of Land Management because of significant range-wide declines from historic levels that may impact the future viability of the species; the cause of the declines are currently unknown 1, 2. Although the species is not classified as Threatened or Endangered, the San Clemente Loggerhead Shrike (L. l. mearnsi) is Endangered throughout its range in California 3. Finally, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources classifies the status of the Loggerhead Shrike as Least Concern 4; however, population trends are decreasing. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: Loggerhead Shrikes, also known as butcherbirds, and Northern Shrikes (L. excubitor) are the only North American species in the family Laniidae. The number and distinctness of subspecies of Loggerhead Shrike varies among reports 5. For the purposes of this document, we follow Yosef (1996) and recognize 9 subspecies. Only L. l. excubitorides is found in Wyoming 6. Description: Loggerhead Shrike is a robin-sized passerine identifiable by its gray back, head, and breast; white chin, throat, and belly; black mask; black primaries and secondaries with a white wing patch; black tail with white outer tail coverts; and small, black, slightly hooked bill 5. -

Ethiopia Endemics

Ethiopia Endemics 11 th - 29 th January 2008 Tour Leaders: Fraser Gear & Cuan Rush Trip Report compiled Tour Leader by Cuan Rush Top 10 birds as voted by participants 1. Prince Ruspoli’s Turaco 2. Lammergeier 3. Arabian Bustard 4. Spotted Creeper 5. Golden-breasted Starling 6. Red-naped Bush-shrike 7. Abyssinian Roller 8. Nile Valley Sunbird 9. Double-toothed Barbet 10. Abyssinian Longclaw 10. Northern Carmine Bee-eater RBT Ethiopia Trip Report January 2008 2 Top 5 Mammals as voted by participants 1. Ethiopian Wolf 2. Gelada Baboon 3. Aardvark 4. Striped Hyena 5. Serval Tour Summary Ethiopia is a land of amazing contrasts, incredible scenery, friendly people and delectable birds and wildlife. Our tour covered the main highlights of the country including the Rift Valley Lakes, the highland plateaus and Juniper Forests of the Bale Mountains, the arid southern region and the wild and seemingly uninhabitable east. The combination of these areas, a great group dynamic and a well-oiled ground team produced a truly awesome tour and ended with a combined total of 59 endemic/near-endemic bird species. The starting point of our adventure was in Addis Ababa, the third highest capital city in the world at 2400m above seal level. A walk in the gardens of our hotel (the afternoon before the official start of the trip) yielded Eurasian Wryneck, Rueppell’s Robin-Chat and Abyssinian Slaty-Flycatcher. We then ventured southwards in order to explore the Rift Valley Lakes and the forests near Wondo Genet. The mudflats, mixed Acacia woodland and grassland and open expanses of the lakes afforded us some good birding.