CORMAC MCCARTHY and the ETHICS of READING By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESCRIPTIVE ETHICS in the SUDAN: an EXAMPLE by TORENORD~NSTAM

DESCRIPTIVE ETHICS IN THE SUDAN: AN EXAMPLE by TORENORD~NSTAM The study of ethical beliefs in the Sudan is a fascinating and more or less unexplored field of research. The purpose of this paper is to give an introductory survey of some of the problems and possible lines of research \vithin this field. I shall first give a general outline of the nature of descriptive ethics, as I see it, then I shall highlight somc of the problems in the field by discussing onc particulnr exainple. Finally, I shall bricfly indicate why research of this nature is of speci~il importance in a developing country like the Sudan. The field of descriptive ethics Descriptive ethics can be defined as the description and analysis of the ethics of individuals and groups. Such a brief definition will introduce the nature of the field, but it certainly stands in need of further explanation. This applies partie- ularly to the key word in the definition, the term "ethics," which can be used in a variety of ways with more or less clear meanings. 1 propose to take the term "ethics" in a wide sense so that any view about what is right and wrong, good and bad, praiseworthy and blame~vorthywill count as a inoral vieu.. An individual's ethics is, then, the system comprising all his values and ideals, all his opinions about right and wrong conduct, all his beliefs about deserts and punishment, responsibility and free will, and so on. In short, an individual's ethics. in this sense, consists of his ideal of life: it is the sum total of his personality ideals, his social ideals, his political ideals, Iiis economic ideals, and so forth. -

The Influence of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick on Cormac Mccarthy's Blood Meridian

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 8-1-2014 The Influence of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick on Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian Ryan Joseph Tesar University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Repository Citation Tesar, Ryan Joseph, "The Influence of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick on Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian" (2014). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2218. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/6456449 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF HERMAN MELVILLE’S MOBY-DICK ON CORMAC MCCARTHY’S BLOOD MERIDIAN by Ryan Joseph Tesar Bachelor of Arts in English University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts – English Department of English College of Liberal Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas August 2014 Copyright by Ryan Joseph Tesar, 2014 All Rights Reserved - THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend the thesis prepared under our supervision by Ryan Joseph Tesar entitled The Influence of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick on Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts - English Department of English John C. -

AP 12 English Literature & Composition

AP 12 English Literature & Composition Summer Reading Assignment Congratulations on your choice to take AP Literature. Students choosing this course are interested in studying literature of various periods and genres and using this wide reading knowledge in discussions of literary topics. This is a college level course that requires careful reading and critical analysis of a work’s structure, style, and themes as well as smaller scale elements, such as the use of figurative language, imagery, symbolism, and tone. Thoughtful discussions and writing about complex, canonical texts in the company of one’s fellow students is our goal. It goes without saying that you should be reading a bit in preparation for this course. Specifically, we ask that you select and read one of the following texts and complete the assignments outlined to help us to build upon a common conversation at the beginning of the year. Reading Assignments: Before beginning your selection, read “How to Mark a Book” by Mortimer Adler. (The essay is easy to find on- line by searching for the title and author) Then choose one of the following texts to read and annotate according to Adler’s description: To the Lighthouse – Virginia Woolf The Scarlet Letter - Nathaniel Hawthorne Blood Meridian – Cormac McCarthy Slaughterhouse Five – Kurt Vonnegut On the Road – Jack Kerouac For Whom the Bell Tolls – Ernest Hemingway The Sound and the Fury – William Faulkner How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accent – Julia The Joy Luck Club- Amy Tan Alvarez Ceremony - Leslie Marmon Silko All of these books are readily available at your local library and from major bookstores. -

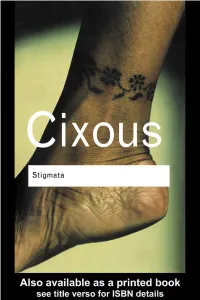

Stigmata: Escaping Texts

Stigmata ‘Hélène Cixous is in my eyes, today, the greatest writer in the French language… Stigmata is henceforth a classic…. One of her most recent masterpieces.’ Jacques Derrida Routledge Classics contains the very best of Routledge publishing over the past century or so, books that have, by popular consent, become established as classics in their field. Drawing on a fantastic heritage of innovative writing published by Routledge and its associated imprints, this series makes available in attractive, affordable form some of the most important works of modern times. For a complete list of titles visit http://www.routledgeclassics.com/ Hélène Cixous Stigmata Escaping texts With a foreword by Jacques Derrida and a new preface by the author London and New York First published 1998 by Routledge First published in Routledge Classics 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge New York, NY 100 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge's collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1998, 2005 Hélène Cixous Index compiled by Indexing Specialists (UK) Ltd, 202 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex BN3 2DJ, UK All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Representations of Politicized

i MEMORIALS FOR THE UNMOURNED: REPRESENTATIONS OF POLITICIZED VIOLENCE IN CONTEMPORARY U.S.-MEXICO BORDER FICTION by PRESTON WALTRIP Bachelor of Arts, 2012 University of Dallas Irving, Texas Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of AddRan College of Liberal Arts Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May, 2016 i Copyright by Preston Wayne Waltrip 2016 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe many thanks, first, to my thesis committee members, whose guidance contributed not only to the completion of this thesis, but also to my development as a scholar. I am especially grateful to Dr. Easterbrook for making his time and expertise available to me from the moment I set foot on campus. I am also thankful to Dr. Colón and Dr. Darda for their direction, advice, and availability throughout this process. I would like to thank my parents for their continued support and encouragement during my time as a graduate student. They believe in me and in the work I’m doing despite not quite understanding why anyone in their right mind would want to do it. Finally, I want to thank my friends: Jacquelyn, who helped me work through many of my ideas for this project; Jamie, who got us free pizza that one time; Chase, who tolerates a perpetually cluttered coffee table and, like me, will gladly sacrifice a few hours of sleep for the sake of a long, philosophical conversation; and all the graduate students in the TCU English department, who have consistently gone out of their way to be kind and supportive to me and to one another. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Normative and Descriptive Aspects of Management Education: Differentiation and Integration

Journal of Educational Issues ISSN 2377-2263 2015, Vol. 1, No. 1 Normative and Descriptive Aspects of Management Education: Differentiation and Integration Gavriel Meirovich (Corresponding author) Department of Management, Bertolon School of Business, Salem State University 352 Lafayette Street, Salem, MA 01930, United States Tel: 978-543-6948 Fax: 978-542-6027 E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 7, 2015 Accepted: May 27, 2015 Published: June 3, 2015 doi:10.5296/jei.v1i1.7395 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5296/jei.v1i1.7395 Abstract This study advocates strongly for clear differentiation and synthesis of descriptive and normative approaches in management education. There is a certain isolation of normative and descriptive theoretical frameworks presented in management courses. Normative frameworks in management explain how organizations should be managed, while descriptive frameworks show how they actually are managed. Significant portions of what we teach in the business curriculum are predominantly descriptive; other parts are mostly normative, or prescriptive. If these domains are not sufficiently connected, the relevance of both approaches diminishes. When one piece of material explains only the current reality without providing tools to improve it, while another piece prescribes steps for improvement that are not grounded in a particular context, students lose interest in both. The paper presents various modes of differentiation and integration between two realms and pertinent ways to recalibrate management courses. Keywords: Normative and descriptive framework, Differentiation, Integration 1. Introduction The purpose of business education is preparing future business professionals for successful careers and meaningful lives. The continued rise of its cost poses difficult questions about the relevance of contemporary business education in general and management education in particular. -

Normative Ethics

Normative ethics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Normative ethics is the new "it" branch of philosophical ethics concerned with Ethics classifying actions as right and wrong. Theoretical Normative ethics attempts to develop a set of rules governing human conduct, Meta-ethics or a set of norms for action. It deals with what people should believe to be right Normative · Descriptive Consequentialism and wrong, as distinct from descriptive ethics, which deals with what people do Deontology believe to be right and wrong. Hence, normative ethics is sometimes said to be Virtue ethics prescriptive, rather than descriptive. Ethics of care Good and evil · Morality Moreover, because it examines standards for the rightness and wrongness of actions, normative ethics is distinct from meta-ethics, which studies the nature Applied of moral statements, and from applied ethics, which places normative rules in practical contexts. Bioethics · Medical Engineering · Environmental Human rights · Animal rights Normative ethical theories Legal · Media Business · Marketing Consequentialism (Teleology) argues that the morality of an action is Religion · War contingent on the action's outcome or result. Some consequentialist theories include: Core issues Utilitarianism, which holds that an action is right if it leads to the most value for the greatest number of people (Maximizes value for Justice · Value all people). Right · Duty · Virtue Egoism, the belief that the moral person is the self-interested Equality · Freedom · Trust person, holds that an action is right if it maximizes good for the Free will · Consent self. Moral responsibility Deontology argues that decisions should be made considering the factors Key thinkers of one's duties and other's rights. -

The Sunset Limited Press Release

588 Sutter Street #318 San Francisco, CA 94102 415.677.9596 fax 415.677.9597 www.sfplayhouse.org PRESS RELEASE VENUE: 533 Sutter Street, @ Powell For immediate release Contact: Susi Damilano August, 2010 [email protected] West Coast Premiere of THE SUNSET LIMITED By Cormac McCarthy Directed by Bill English September 28 through November 6th Press Opening: October 2nd San Francisco, CA (August 2010) - The SF Playhouse (Bill English, Artistic Director; Susi Damilano, Producing Director) are thrilled to announce casting for the West Coast Premiere of The Sunset Limited by Cormac McCarthy which opens their eighth season. “The theme of the 2010-2011 season is ‘Why Theatre?”, remarked English. “Why do we do theatre? How does theatre serve our community?” Each of our selections for our eighth season will give a different answer to these questions. Based on the belief that mankind created theatre to serve a spiritual need in our community, our riskiest and most challenging season yet will ask us to face mankind’s deepest mysteries. We open the season with one of the most powerful writers of our time, Cormac McCarthy (All the Pretty Horses, The Road, No Country for Old Men). The play, billed as “a novel in play form” brings us into a startling encounter on a New York subway platform which leads two strangers to a run-down tenement where they engage in a brilliant verbal duel on a subject no less compelling than the meaning of life. TV and film star Carl Lumbly (Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train, Alias, Cagney & Lacey) returns to the SF Playhouse to reunite with local favorite Charles Dean (White Christmas, Awake and Sing!) after having performed together in Berkeley Rep’s 1997 production of Macbeth. -

A Translation Autopsy of Cormac Mccarthy's The

A TRANSLATION AUTOPSY OF CORMAC MCCARTHY’S THE SUNSET LIMITED IN SPANISH: LITERARY AND FILM CODA Michael Scott Doyle [T]he translation is not the work, but a path toward the work. —José Ortega y Gasset, “The Misery and Splendor of Translation,” 109 We now have the personal word of the author’s to be transformed into a personal word of the trans- lator’s. As always with translation, this calls for a choice among synonyms. —Gregory Rabassa, If This Be Treason: Translation and Its Dyscontents, 12–13 Glossary of the Codes Used S1 = the first Spanish TLT version to be analyzed = Y1,theliterary translation-in-progress S2 = the second Spanish TLT version to be analyzed = Y2, the final, published literary translation S3 = the third Spanish TLT version to be analyzed = the movie subtitles S4 = the fourth Spanish TLT version to be analyzed = the movie dubbing SLT-E = Source Language Text English (Translation from English) SLT-X = Source Language Text in X Language (Translation from Language X) TLT = Target Language Text TLT-S = Target Language Text Spanish (translation into Spanish) Y1 = Biopsy Stage of a Translation = the Translation-in-Progress (in the Process of Being Translated) Y2 = Autopsy Stage of a Translation = the Final Published Translation (Post-process of the Act of Translating, an Outcome of Y1) Introduction: From Biopsy to Autopsy The literary translation criticism undertaken in the Sendebar article “A Translation Biopsy of Cormac McCarthy’s The Sunset Limited in Spanish: Shadowing the Re-creative Process” antici- pates a postmortem -

Blood Meridian and the “Creation” of Historical Narrative by Josh Boissevain

Blood Meridian and the “Creation” of Historical Narrative by Josh Boissevain Each age tries to form its own conception of the past. Each age writes the history of the past anew with reference to the conditions uppermost in its own time. -Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of History History is a strong myth, perhaps . the last great myth. It is a myth that once subtended the possibility of an ‘objective’ enchainment of events and causes and the possibility of a narrative enchainment of discourse. The age of history, if one can call it that, is also the age of the novel. -Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation In one sense, Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West is a book about the West; it is a book that bridges the gap between the “old” mythological and the “new” revisionist Western and creates a new direction for the genre to follow—that of a more realistic myth. It uses and inverts several classic aspects of the cliché western and pairs them with themes and issues associated with modern historical interpretations of the West, generating a new type of Western. It is an example of what Richard Slotkin would term a productive revision of myth. In another sense, Blood Meridian is a book about much more than the West; it is a book about history and the representation of history. It is a critique on the process in which “history,” (the textual representation of past events where thematic sequence and significance are artificially imposed) is created—and continuously recreated—to fit the hegemonic cultural narrative. -

Music Recommendation and Discovery in the Long Tail

MUSIC RECOMMENDATION AND DISCOVERY IN THE LONG TAIL Oscar` Celma Herrada 2008 c Copyright by Oscar` Celma Herrada 2008 All Rights Reserved ii To Alex and Claudia who bring the whole endeavour into perspective. iii iv Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Xavier Serra, for giving me the opportunity to work on this very fascinating topic at the Music Technology Group (MTG). Also, I want to thank Perfecto Herrera for providing support, countless suggestions, reading all my writings, giving ideas, and devoting much time to me during this long journey. This thesis would not exist if it weren’t for the the help and assistance of many people. At the risk of unfair omission, I want to express my gratitude to them. I would like to thank all the colleagues from MTG that were —directly or indirectly— involved in some bits of this work. Special mention goes to Mohamed Sordo, Koppi, Pedro Cano, Mart´ın Blech, Emilia G´omez, Dmitry Bogdanov, Owen Meyers, Jens Grivolla, Cyril Laurier, Nicolas Wack, Xavier Oliver, Vegar Sandvold, Jos´ePedro Garc´ıa, Nicolas Falquet, David Garc´ıa, Miquel Ram´ırez, and Otto W¨ust. Also, I thank the MTG/IUA Administration Staff (Cristina Garrido, Joana Clotet and Salvador Gurrera), and the sysadmins (Guillem Serrate, Jordi Funollet, Maarten de Boer, Ram´on Loureiro, and Carlos Atance). They provided help, hints and patience when I played around with the machines. During my six months stage at the Center for Computing Research of the National Poly- technic Institute (Mexico City) in 2007, I met a lot of interesting people ranging different disciplines.