Interview with Arnold Dreyblatt Christoph Cox, 1998 CC: You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abendprogramm Nicolas Collins, Alvin Lucier, Arnold Dreyblatt

NICOLAS COLLINS Oehring, Nicolas Collins, Lou Reed, KONRAD SPRENGER SONIC ARTS LOUNGE Der New Yorker Performer, Kompo- MERZBOW a.k.a., Masami Akita, (JÖRG HILLER) NICOLAS COLLINS/ALVINLUCIER nist und Klangkünstler, Jahrgang Radu Malfatti, Bernhard Guenter, Der Komponist, Musiker und Pro- 1954, studierte bei Alvin Lucier Mario Bertoncini (nuova conso- duzent ist 1977 in Lahr geboren NICOLAS COLLINS ARNOLDDREYBLATT Komposition und arbeitete viele nanza) und Keiji Hainoand zusam- und lebt heute in Berlin. Sprenger Roomtone Variations Jahre mit David Tudor und der men. Der Schwerpunkt der Arbeit machte als Produzent Aufnahmen für Computer und Instrumentalisten (2013) Gruppe Composers Inside Electro- von Friedl liegt beim inside-piano, mit Künstlern wie Ellen Fullman, T HEO RCHESTRAOFEXCITEDSTRINGS nics zusammen. Collins ist Pionier den Spieltechniken und Möglich- Arnold Dreyblatt, Robert Ashley Fassung für Klavier im Berghain (2014) UA 15’ in der Verwendung von selbstent- keiten des Innenklaviers. und Terry Fox. Er spielte mit Bands 18 03201422UHR wickelten elektronischen Schalt- wie Ethnostress oder Ei sowie mit Reinhold Friedl, Klavier kreisen, sogenannten Handmade dem Künstlerkollektiv Honeysuckle Electronics, Mikrocomputern, ARNOLD DREYblatt Company. Seit 2000 spielt er regel- BERG HAIN Radiogeräten, aufgelesenem geboren 1953 in New York, ist Kom- mäßig mit den Komponisten Alvin LUCIER Klangmaterial und verfremdeten ponist, Performer und Bildender Arnold Dreyblatt und Ellen Fullman. MAERZMUSIKFESTIVALFÜRAKTUELLEMUSIK Musikinstrumenten. Unter ande- Künstler. Er studierte bei Pauline Gegenwärtig konzentriert er sich The Bird of Bremen Flies Through the Hou- rem hat er eine Kombination von Oliveros, La Monte Young und Alvin auf Live-Performances mit ses of the Burghers Posaune und Computer entworfen, Lucier und lebt seit 1984 in Berlin. -

ELLEN FULLMAN & KONRAD SPRENGER Title

out on may 1st on Choose Records (Berlin) and exclusively distributed by a-musik: ELLEN FULLMAN & KONRAD SPRENGER, ORT. CD is ready for shipping now, LP will be available in mid-april. Pre-orders are welcome. artist: ELLEN FULLMAN & KONRAD SPRENGER title: Ort label: CHOOSE format: LP cat #: Choose2LP artist: ELLEN FULLMAN & KONRAD SPRENGER title: Ort label: CHOOSE format: CD cat #: Choose2CD "Ellen Fullman, composer, instrument builder and performer was born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1957. Irish-American, and of partial Cherokee Indian ancestry, with the distinction of having been kissed by Elvis at age one, Fullman studied sculpture at the Kansas City Art Institute before heading to New York in the early nineteen-eighties. In Kansas City she created and performed an amplified metal sound-producing skirt and wrote art-songs which she recorded in New York for a small cassette label. In 1981, at her studio in Brooklyn she began developing her life-work, the 70 foot (21 meter) “Long String Instrument”, in which rosin-coated fingers brush across dozens of metallic strings, producing a chorus of minimal organ-like overtones which has been compared to the experience of standing inside an enormous grand piano. Fullman, subsequently based in Austin, Texas; Seattle, Washington and now Berkeley, California has recorded extensively with this unusual instrument (with recordings on New Albion and Niblock’s XI label among others) and has recently collaborated with such luminary figures as the Kronos Quartet and with cellist Frances-Marie Uitti. In 2000, Fullman received a grant to live and work in Berlin for one year. -

WORLD from a SINGLE STRING Terry De Castro, Los Angeles, 2010

WORLD FROM A SINGLE STRING Terry de Castro, Los Angeles, 2010 “…He’s forged his own way and came up with systems that no one formally trained in foundation would have come up with; he breaks the rules from the ground up.” --Rhys Chatham “…The entire history of my work in music has been derived from a single, subjective experience with sound.” --Arnold Dreyblatt Arnold Dreyblatt can’t recall exactly where he read it, but anthropologists seem to suggest that the first primary string instrument preceded the first weapon. The implication here, appealingly idealistic, is that music is more primal than even violence, and that the first stringed bow generated a musical vibration long before it ever launched an arrow. Few composers exemplify the basic, fundamental, original aspects of music making as exquisitely as Arnold Dreyblatt. He strips everything down and builds it back up again from its auspicious beginnings, from a time when the first human being created a sound not for utility, but for the sake of art. With slight formal training in composition or traditional theory, his initial desire to make music came from an “amateur” interest in the physics of vibration and the raw materials of sound. From this starting point arose the fundamental question: what happens when I excite this string? The rest of his music grew from that premise, and his experiments in acoustics and instrument construction led him into an increasingly complex and subtle world. He discovered that what does happen is that a fragile system of existing, archetypical tones and rhythms reveals itself, a world he has been exploring ever since. -

Some Personal Musical History Stories by Arnold Dreyblatt, 1989

Some Personal Musical History Stories by Arnold Dreyblatt, 1989 New York My grandfather Max Dreyblatt played clarinet professionally in ‘pit’ orchestras for vaudeville and silent films in New York City. About to be drafted into World War One, he enlisted with his buddies from The Bronx as a military band which spent the war playing patriotic music in the trenches in France. Their job was to inspire the young boys in the infantry to jump out of the trenches only to be massacred. His grandparents, immigrants from Galicia operated a family ensemble entitled La Troupe Maximov which presented evenings of Gypsy, Russian and Turkish music during the late 19th century in Vienna. After one and a half years of piano lessons at age 7 my teacher, having taught me with a number system of her own devising, tried to introduce me to the five line staff. This new system, having proved itself unintelligible to me, signaled the end of piano lessons. Forced into Recorder class at age 8 in the local elementary school, I moved my fingers without blowing onto the instrument. After three months I was called upon to perform a solo and I was thereupon expelled. The arrival of the Beatles in 1963 prompted numerous attempts at learning the guitar, but lessons were repeatedly terminated as I was consistently rated tone deaf and unteachable. I was almost 22 when I first met La Monte Young after a concert of his on Wooster Street. I had read his book Selected Writings as a film and video student in Buffalo. -

ARNOLD DREYBLATT Choice LP Choose Records Choose 7 Release Date: April 25 Vertrieb: A-Musik

ARNOLD DREYBLATT Choice LP Choose Records Choose 7 Release date: April 25 Vertrieb: A-Musik http://www.choose-records.de http://www.dreyblatt.de Often characterized as the most rock-oriented of American minimalists, Dreyblatt has cultivated a strong underground fan base for his transcendental and ecstatic music. Now, for his latest issue on Choose Records, Berlin's Jörg Hiller aka Konrad Sprenger has made his own "Choice" from Arnold Dreyblatt's own extensive archive of live recordings, ranging from over thirty years of live performances from 1977 to 2007. This is very much a "collectors' LP", which plays as a carefully curated sonic selection, rather than as a chronological sequence of individual recordings. The collection ranges from seminal recordings by many of the historical ensembles who performed as Dreyblatt's Orchestra of Excited Strings in the States and in Europe, to some of Dreyblatt's most compelling solo projects making for some very surprising listening, especially for those who may already know Dreyblatt's currently available studio recordings. Meticulously mastered by Rashad Becker with an artful cover design by Hendrik Schwantes, "Choice" is a must for Dreyblatt fans and afficiandos of historical minimalism. Biography Arnold Dreyblatt (b. New York City, 1953) is an American media artist and composer. He has been based in Berlin, Germany since 1984. In 2007, Dreyblatt was elected to lifetime membership in the visual arts section at the German Academy of Art (Akademie der Künste, Berlin). He is currently Professor of Media Art at the Muthesius Academy of Art and Design in Kiel, Germany. His early activities in music and performance included the albums Nodal Excitation, Propellers In Love and the opera project Who's Who in Central and East Europe 1933. -

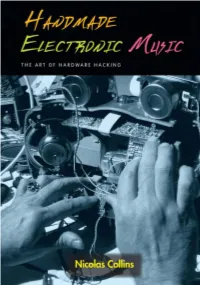

Handmade Electronic Music : the Art of Hardware Hacking / by Nicolas Collins ; Illustrated by Simon Lonergan

RT75921_FM.indd 1 2/9/06 7:24:43 PM Disclaimer Despite stringent eff orts by all concerned in the publishing process, some errors or omis- sions in content may occur. Readers are encouraged to bring these items to our attention where they represent errors of substance. Th e publisher and author disclaim any liability for damages, in whole or in part, arising from information contained in this publication. Th is book contains references to electrical safety that must be observed. Do not use AC power for any projects discussed herein. Th e publisher and the author disclaim any liability for injury that may result from the use, proper or improper, of the information contained in this book. We do not guarantee that the information contained herein is complete, safe, or accurate, nor should it be considered a substitute for your good judgment and common sense. CCollins_RT75921_C000.inddollins_RT75921_C000.indd iiii 22/23/2006/23/2006 111:54:061:54:06 AAMM Nicolas Collins Illustrated by Simon Lonergan New York London Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business RT75921_FM.indd 2 2/9/06 7:24:45 PM RT75921_RT75913_Discl.fm Page 1 Monday, February 27, 2006 3:18 PM Published in 2006 by Published in Great Britain by Routledge Routledge Taylor & Francis Group Taylor & Francis Group 270 Madison Avenue 2 Park Square New York, NY 10016 Milton Park, Abingdon Oxon OX14 4RN © 2006 by Nicolas Collins Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10987654321 International -

“Have You Met... Arnold Dreyblatt” Adela Lovric, 2016 for Its 19Th

“Have you met... Arnold Dreyblatt” Adela Lovric, 2016 For its 19th edition of "Appropriating Language" series, organised in partnership with the Berlin Art Week, Manière Noire shows an installation by the media artist and composer Arnold Dreyblatt. We spoke with Arnold about his ongoing show "Replica" and a number of upcoming projects, as well as his decades-long presence in the art scenes of New York and Berlin. Can you tell us more about your piece, "Replica", currently displayed at Manière Noire? "Replica" is one of a series of works in which micro-image storage techniques are contrasted with the burocratic process of data destruction or obliteration. Our dilemma is that we are trapped in a dialectic of saving and loss, finding and disapearance. Microfilm and microfiche are both relatively stable document archiving technnologies, in comparison to the digital, and they are here presented as unseen behind framed pseudo-artworks with peepholes. We peer into a lens and aparatus for viewing the text, which was itself developed as a hand-readable microfiche device – developed for observation by the East German intelligence services. Through intensive magnification, we read administrative texts on the "norms" and "standards" for intentional disapearance of data. These are all themes that I have dealt with in related works. What are you mainly concerned with in your art practice in general? My artistic practices have been realized in a diverse variety of formats and media contexts over the years, such as music composition and sound art, contemporary opera, performance as mass public readings, media installation with digital media, and artistic research projects. -

Product of Culture-Clash: the Theatre of Eternal Music And

Product of Culture-Clash: social scene, patronage and group dynamics in the early New York Downtown scene and the Theatre of Eternal Music1 Brian Bridges Introduction This article will explore the background to the establishment of the Downtown avant- garde art and music scene in New York, including a survey of the role of the experimental composer in American music. It will investigate cultural interactions and influences between some of the main players in the early Downtown scene, focusing in particular on the Theatre of Eternal Music (TEM), the ensemble formed in the 1960s by New York-based “founding-father” Minimalist La Monte Young. It will examine some of the cross-pollination which occurred between the group and the environment in which it developed and will briefly survey the manner in which historical accounts have attributed varying degrees of credit to members of the group, along with a brief account of the current dispute between Young on the one hand and Tony Conrad and John Cale on the other. 1. Scene-setting The art world in 1960s New York enjoyed the healthy combination of low rents in Downtown spaces (which could be retrofitted for both accommodation and display purposes) and a fortuitous proximity to rich patrons. In keeping with the restless Social Darwinistic nature of the city, these patrons were often interested in funding artistic endeavours which evoked and reflected a certain “edginess”. Along with the changing roles of curators, dealers and galleries in promoting the works of living artists to an unprecedented degree, this created a distinctly favourable situation for many visual artists. -

Acoustic Ephemera and Transmissions Of

A thesis presented to the Faculty of Conservatory of Music Brooklyn College in Spring 2020 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of M.F.A. in Sonic Arts Contents 8 38 10 46 18 52 24 56 60 32 66 tell me about yourself where were you in the eighties? you drink prosecco, why? I speak to you now from an opening eye from a spiritual buttress factory I hope for you to reap the burning of light that hits us from the sky what’s your restaurant? who are your people? that you wait for the most? who is your bearer? what are you wearing? who let you in? will call out if you faint when I come down? who is the heaviest child you’ve ever held? talking inwards shouldn’t be so hard to think —Morgan Vo Acoustic Ephemera and Transmissions of Weakness the unstable chemistry of plastic film and accompanies a collection of scores, grouped magnetic tape reels—have been reimagined together as part of an ongoing series entitled as metaphors for an artistic mode that values Folded Cyanotypes. Initiated via an evolving tactile sensitivity, contingency, and the affective instrumentarium of resonant zithers that potential of weakness. are augmented by electronics, the music Partly inspired by a series of works by of this portfolio encourages heightened artist Josiah Valle Ellis, the photographic environmental perception, as well as exper- process of the cyanotype (a kind of photogram iential associations of touch, memory, and commonly used for making blueprints) musical lineage. Through a consideration of clarifies this compositional practice. -

Tony Conrad by Nils Jendri

Tony Conrad by Nils Jendri. 2006. Index: 1. Biography 2. Theater of Eternal Music 3. The Flicker 4. Concept Art: Tony Conrad and the early minimalism 5. Tony Conrad and the authorship 6. Musicselection 7. Filmselection 8. Bibliography 9. Container 1. Biography Tony Conrad, a/k/a Anthony S. Conrad, (*1940). Since the early 60`s he started working as a Experimental filmmaker, the biggest attention he get is with his first film „The Flicker„ (1965). He also started working as a composer and sound-artist (he get into it through a lecture by Stockhausen in Harvard in 1958), currently he primary works as a teacher (University of Buffalo) and writer (for example in the current issue of the Millennium Film Journal (No.45). There he puplished the text Is This Penny Ante or a High Stakes Game? / An Interventionist Approach to Experimental Filmmaking). He graduate at Harvard University in 1962 (major Mathematics). After that Conrad relocated to New York, where he became interested in the underground music Scene. Here he met the Composer and Saxophonist LaMonte Young who at the time was leading an improvisational group „…a proto-minimalist jazz mutation. Soon, Billy Name left and Conrad joined, beginning by playing only an open fifth drone, and moving the small ensemble towards a "Dream Music" that would profoundly influence subsequent composers.“ (http://media.hyperreal.org/zines/est/intervs/conrad.html) Later Conrad had also begun channelling his energies into filmmaking, working as a sound engineer and technical advisor on the experimental features with the experimental film icon Jack Smith. -

SOUNDGAZING: 15 Years of Aural Graphics by Jeff Hunt 1 Photographs and Original Artworks by Bradly Brown

SOUNDGAZING: 15 Years of Aural Graphics by Jeff Hunt 1 Photographs and Original Artworks by Bradly Brown altering music and innovative artwork. Allegedly, when Wilson was told that one of his elaborately packaged releases for Factory Records was actually going to lose money each time it sold, he said with genuine glee, “That’s okay, because we’re going to sell fuck-all copies!” What beautiful logic. In Brit-speak, “fuck- Factories of Immaculate Fuck-All all” is next to nothing. In a similar fashion, over its nearly two-decade, century- straddling existence, TotE has not only operated on handshake deals (like Factory) but also obsessed solely over the immaculate aesthetics of its releases, shunning commercialism, even damning it, for the sake of art. eff Hunt once had a vivid waking dream involving visions of the saints, Jin which perfectly aligned, rectangular portals opened up in a high, A friend and former colleague likes to say that Jeff Hunt has “the best eye in the vaulted ceiling, radiating silver, black and glowing white. “Trust me to business.” It’s true, and his impeccable taste seems natural and effortless, an hallucinate in Hunt/Archie art direction,” he quipped. The Archie he was impression only enhanced by the stark elegance of the TotE designs. No doubt 6 7 talking about would be Susan Archie, the Grammy-winning designer he’s had this aptitude and flair from day one, which brings to mind another with whom Jeff has collaborated in over 60 releases for Table of the quote it’s hard to resist citing here. -

ARNOLD DREYBLATT (B. New York City, 1953) Is an American Media Artist and Composer

ARNOLD DREYBLATT ARNOLD DREYBLATT (b. New York City, 1953) is an American media artist and composer. He has been based in Berlin, Germany since 1984. In 2007, Dreyblatt was elected to lifetime membership in the visual arts section at the German Academy of Art (Akademie der Künste, Berlin). He is currently Professor of Media Art at the Muthesius Academy of Art and Design (Muthesius Kunsthochschule) in Kiel, Germany. EDUCATION 1980-82 Wesleyan University, Studies of Composition und Ethnomusicology, (M. A. 1982) Composition studies with Alvin Lucier 1975-77 State University of New York, Buffalo, Studies at the Center for Media Study (M. A. 1976) Videoart Studies with Woody & Steina Vasulka Film Studies with Hollis Frampton and Paul Sharits Composition Studies with Pauline Oliveros, Morton Feldman and John Cage Private Composition Studies and Tape Archivist, La Monte Young (with support by the Dia Art Foundation) Assistant for Shigeko Kubota and Nam June Paik, Video Program, Anthology Film Archives, New York 1970-74 State University College, New Paltz, New York (B.A. 1974) Studies in Literature and New Media Arts with Irving J. Weiss, Studies in Electronic Music with the Composer Joel Chadabe, State University of New York, Albany Electronic Music with David Moulton, Rhinebeck, New York Community Media Project, New Paltz, New York Summer Study in Archaeology, University of Tel Aviv SOLO EXHIBITIONS AND PROJECTS 2021 “Warm-Up”, installation, Yellow Solo Project Space, Berlin 2019 “The Resting State”, Showroom, NBK (Neue Berliner Kunstverein),