THE EXPERIENCE of FEMALE JOURNALISTS of COLOR on TWITTER Proposal for a Professiona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read the April 2019 Issue

The University of Memphis Meeman Matters Newsletter of the Department of Journalism and Strategic Media April 2019 WHAT’S Documentary examines INSIDE issues, activism in Memphis Accreditation renewed once more ❱❱ 2 Ad award named for Utt ❱❱ 3 Students earn online news honors ❱❱ 3 Waters joins Institute ❱❱ 3 JRSM awards a big hit ❱❱ 4 WUMR gives PHOTO BY WILL SUGGS radio skills for Journalism student Caleb Suggs interviews professor Otis Sanford as part of the documentary students ❱❱ 5 Once More at the River: From MLK to BLM. The film premiered in January 2019. BY WILLIAM SUGGS Museum and found colleagues to collab- Jemele Hill orate at the UofM. They included journal- packs in a The documentary film “Once More At ism professor Joe Hayden and Department crowd ❱❱ 6 The River: From MLK to BLM,” which exam- of History chair Aram Goudsouzian. “Ev- ined activism in Memphis since the Civil erything happened pretty quickly,” Coche Rights Movement, premiered on Jan. 22 to said. She decided on the theme in late 2016, 'A Spy in a full house at the UofM’s UC Theatre. and by early February 2017, the group had Canaan' gets Roxane Coche, the film’s director and one submitted its first grant proposal. notice ❱❱ 7 of its producers, said the idea for the docu- Faculty and students of the University of mentary came in 2016 upon the realization Memphis’ departments of Journalism and Student ad that the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther Strategic Media and History helped produce King, Jr.’s assassination was approaching. the film, which also received a grant and team scores “Social justice and civil rights are such support from organizations including the high ❱❱ 8 an important topic that I decided to pitch National Civil Rights Museum and Human- the idea for a full-length documentary in- ities Tennessee. -

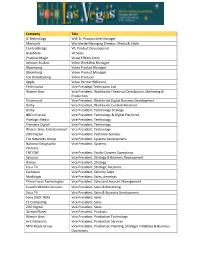

Company Title G-Technology WW Sr. Product Line Manager Microsoft

Company Title G-Technology WW Sr. Product Line Manager Microsoft Worldwide Managing Director, Media & Cable Contentbridge VP, Product Development GrayMeta VP Sales Practical Magic Visual Effects Artist Amazon Studios Video Workflow Manager Bloomberg Video Product Manager Bloomberg Video Product Manager Fox Broadcasting Video Producer Apple Video Partner Relations Technicolor Vice Presidept Technicolor Ltd Warner Bros. Vice President, Worldwide Theatrical Distribution, Marketing & Production Paramount Vice President, Worldwide Digital Business Development Dolby Vice President, Worldwide Content Relations Dolby Vice President, Technology Strategy NBCUniversal Vice President, Technology & Digital Platforms Pixelogic Media Vice President, Technology Premiere Digital Vice President, Technology Warner Bros. Entertainment Vice President, Technology ZOO Digital Vice President, Technical Services Fox Networks Group Vice President, Systems Development National Geographic Vice President, Systems Partners TNT/TBS Vice President, Studio Content Operations Synovos Vice President, Strategy & Business Development Disney Vice President, Strategy You.i TV Vice President, Strategic Accounts Cartesian Vice President, Security Sales MarkLogic Vice President, Sales, Americas Prime Focus Technologies Vice President, Sales and Account Management Crawford Media Services Vice President, Sales & Marketing You.i TV Vice President, Sales & Business Development Sony DADC NMS Vice President, Sales T2 Computing Vice President, Sales ZOO Digital Vice President, Sales -

Startup Culture Isn't Just a Fad, Signals CXO Money Snapdeal Raises AGE of INVES1MENI'5 $500 M More'in a Fresh Round

The Economic Times August 3, 2015 Page No. 1 & 13 GUNGHOA poll of 100 C-sutte occupiers across companies has revealed that as ma~60% CXO-Ievel execs in India invested a portion of their wealth in startups Startup Culture isn't Just a Fad, Signals CXO Money Snapdeal Raises AGE OF INVES1MENI'5 $500 m more'in a Fresh Round 2VEARS Alibaba, Foxconn and 3YEARS_ SoftBank pick up stakes 4 YEARS. DealDIIest IN JA/IIUMv, AU- A MIX OFVALUA- 5-10YEARS baba started talks tIon mIsmaId1IS with SnapdeaI to and demand for !!10VEARS_ ,,-pick-,---,UP-,--stake~_-----lper10nnaIlCIHed 11 MAY,FOIIaNI metrIcs dI!Iayed NORESPONSE. too evinced interest dosure.of deal planned to open their wallets to this as- [email protected] set class in the coming months. As many as 79 CXOs said they would New Delhi: Jasper Infotech, which TEAM ET recommend investing in startups to oth- owns and operates online marketplace ers' although with an important caveat Snapdeal.com, has raised fresh capi- that these investments were risky and As many as six in 10 CXO-levelexecu- tal, estimated at about $500 million, in tives in India have invested a portion of investors needed to make them with a new round led by Chinese e-com- their wealth in startups, an ET poll of their eyes fully open. merce giant Alibaba Group and Tai- 100 randomly selected C-Suite occu- wanese electronics manufacturer piers across compa- Investlnlln Friends' Ventures •• 13 Foxconn, tech news startup Re/Code NBFCSQUEUE nies in a range of in- claimed late on Sunday. -

Attendance Audit Summary

ATTENDANCE AUDIT SUMMARY CES® 2020 January 7-10, 2020 Las Vegas, Nevada CES.tech Letter from Consumer Technology Association (CTA)® For more than 50 years, CES® has served as a global platform for companies to share innovative technology with the world. In these challenging times, CES showcases the spirit of innovation and brings together energy and creativity that will enable technology to make the world healthier, safer, more resilient and connected. CES 2020 featured transformative technologies such as artificial intelligence, the 5G ecosystem and mobile connectivity. CES 2020 inspired and connected major industries across the globe and highlighted trends that are now more important than ever, including non-traditional tech and tech for good. We are certain that technology, including the innovations at CES, will help energize the global economy and pull the world through the current crisis to emerge safer and stronger than before. CES 2020 hosted 4419 exhibiting companies across more than 2.9 million net square feet and attracted a total attendance of 171,268, including 6517 members of media. This result aligns with our strategy of managing attendee numbers and attracting the most highly qualified attendees. CES is one of a select group of trade shows that follow the strict auditing requirements set by UFI, the Global Association of the Exhibition Industry. CES adheres to these requirements to ensure that you have the most detailed and accurate information on CES’s trade event attendance. To help you succeed and grow your business, we are proud to provide you with this independently audited attendance data in our CES 2020 Attendance Audit Summary. -

In the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE STEPHEN G. PERLMAN, REARDEN LLC, a California limited liability company, and ARTEMIS NETWORKS LLC, a Delaware limited liability company, Plaintiffs, Civil Action No. 10046-VCP v. VOX MEDIA, INC., a Delaware corporation, Defendant. MEMORANDUM OPINION Date Submitted: June 10, 2015 Date Decided: September 30, 2015 Matthew E. Fischer, Esq., Jacob R. Kirkham, Esq., Jacqueline A. Rogers, Esq., POTTER ANDERSON & CORROON LLP, Wilmington, Delaware; Neville L. Johnson, Esq., Douglas L. Johnson, Esq., James T. Ryan, Esq., JOHNSON & JOHNSON, LLP, Beverly Hills, California; Attorneys for Plaintiffs, Stephen G. Perlman, Rearden LLC, and Artemis Networks LLC. Peter L. Frattarelli, Esq., ARCHER & GREINER, P.C., Wilmington, Delaware; Attorneys for Defendant, Vox Media, Inc. PARSONS, Vice Chancellor. This is an action by a Delaware limited liability company (“LLC”), a California LLC, and an entrepreneur seeking equitable relief and money damages against a Delaware corporation for defamation. The corporation owns and operates a website that, in 2012, published an allegedly defamatory article about a non-party Delaware corporation that is affiliated closely with the Delaware LLC and the entrepreneur. After the website rewrote substantially the article that same day and admitted publicly that it was not vetted properly, the website published another article several days later that the plaintiffs allege is false and defamatory. Then, in 2014, the website published an article about the Delaware LLC that, in its first sentence, referenced and hyperlinked the 2012 articles, allegedly repeated and enhanced the original statements, and imputed those allegedly false and defamatory statements to the Delaware LLC. -

Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Digest

Diversity Equity & Inclusion Digest May 2020 DEI and COVID-19 What to be aware of as we experience this pandemic together... COVID-19 and Health Inequities Four UVA doctors helped raise a national alarm about the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on minority communities. They discuss what they are seeing and what can be done. COVID-19 and Privilege New York Times Opinion columnist Charles Blow argues that as Covid-19 continues to impact our globe, encouraged practices such as staying at home and social distancing become privileges that not all individuals are able to abide by. Victor J. Blue for The New York Times COVID-19 and the Working Class Such a change would be a return to a 1950s- style view of the working class, in which low- wage jobs conferred a sense of dignity. “You viewed yourself as the backbone, the heart and soul of America,” Gest said. No one is more essential than the person bringing you food at the end of a long, frightening week. Page 1 Diversity Equity & Inclusion Digest May 2020 Some Good News with John Krasinski... We're all in need of some good news and there are a lot of amazing people everyday helping us laugh, cry, and unite in ways we've never thought possible before. Just another great one is John Krasinski's Some Good News updates broadcast live from his home with some great surprise special guests - Enjoy! Episode 1: A Twitter Call for Some Good News + Steve Carell Episode 2: Do you love Hamilton? Episode 3: Are you missing baseball right now? Cue the tears, cue the joy - what is YOUR good news? COVID-19 Emergency Assistance Asistencia de Emergencia COVID-19 Assistance d'ugence COVID-19 ENGLISH/ESPANOL/FRANCAIS CLICK HERE/HAGA CLIC AQUI/CLIQUEZ ICI Page 2 Diversity Equity & Inclusion Digest May 2020 Cville Craft Aid + UVA = PPE Success! Melissa Goldman, manager of the School of Architecture’s FabLab, one of the dozens of maker spaces on Grounds, is collaborating with UVA Engineering’s Sebring Smith, shop supervisor at Lacy Hall. -

Anti–Racism Resources So Many New Yorkers (And People of Color Living in America) Know There Are Two Sets of Rules and Two Sets of Justice in This City and Country

Anti–Racism Resources So many New Yorkers (and people of color living in America) know there are two sets of rules and two sets of justice in this city and country. However, the mayor must provide some real leadership these last months in office to move the needle on racial and police equity…as promised. Mr. Mayor, Please Focus. The Amsterdam News, May 13, 2020 • Christina Greer, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Political Science, Fordham University Themes: Self-Care; Caring for Black People; Articles; Books Jesuit Resources on Racism: Ignatian Solidarity Network–Racial Justice Self-Care • How black Americans can practice self-care... And how everyone else can help, Elizabeth Wellington, 2020. • 4 Self-Care Resources for Days When the World is Terrible, Miriam Zoila Pérez, 2020. Demonstrating Care for Black People • Your Black Colleagues May Look Like They’re Okay — Chances Are They’re Not, Danielle Cadet, Refinery 29, 2020. • Before You Check In On Your Black Friends, Read This, Elizabeth Gulino, Refinery 29, 2020. Articles • Around the world, the U.S. has long been a symbol of anti-black racism, Dr. Nana Osei-Opare, The Washington Post, 2020. • Racism Won’t be Solved by Yet Another Blue Ribbon–Report, Adam Harris, The Atlantic, 2020. • The assumptions of white privilege and what we can do…, Bryan N. Massingale, National Catholic Reporter, 2020. • The NFL Is Suddenly Worried About Black Lives, Jemele Hill, The Atlantic, 2020. • Performative Allyship is Deadly (Here’s What to Do Instead), Holiday Phillips, Forge–Medium, 2020. • Talking About Race: A Conversation with Ijeomo Oluo and Ashley Ford, Fordham News, 2019. -

Fngtf BOSTON, MA 02203 HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, and PENSIONS P: 617- 565-3170

ELIZABETH WARREN UNITED STATES SENATE MASSACHUSETTS WASHINGTON, DC 20510-2105 P: 202- 224-4543 COMMITTEES: 2400 JFK FEDERAL BUILDING BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS 15 NEW SUDBURY STREET tlnitfd ~tGtfS ~fnGtf BOSTON, MA 02203 HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS P: 617- 565-3170 ARMED SERVICES 1550 MAIN STREET SUITE 406 SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON AGING SPRINGFIELD, MA 01103 P: 413- 788- 2690 www.warren.senate.gov September 4, 2019 The Honorable Mike Pompeo Secretary U.S. Department of State 2201 C Street, NW Washington, DC 20520 Dear Secretary Pompeo: I am writing to request information regarding recent reports that Vice President Mike Pence patronized President Donald Trump's Trump International Golf Links & Hotel Doonbeg while in Ireland - at the "suggestion" of the President. 1 This transaction - another example of what appears to be open corruption in this administration - deepens my concerns about the ongoing ethics issues related to the President's continued financial relationship with the Trump Organization and the abuse of taxpayer funds to enrich the President and his family through their business interests. During his two-day visit in Ireland earlier this week, Vice President Pence stayed at the Trump International Hotel in Doonbeg and "[flew] the hour-or-so into Dublin [on the other side of Ireland] for official meetings," rather than staying at a hotel in Dublin a short drive away.2 The Vice President's chief of staff indicated that the President encouraged the Vice President to stay at his hotel, telling him, "[Y]ou should stay at my place."3 The Vice President's decision to trek across country is "clearly not convenient. -

May 15, 2020 COVID-19 Digest

And just like that, another week is coming to an end! As we wrap up the 7th week of the term at PSU, we want to congratulate the Scholars attending semester universities and colleges for completing their academic year. The EXITO staff and faculty are so proud of you all for getting it done, especially given all the uncertainty and change this spring. When we asked Scholars, "How are you feeling this week?" this is what a few of them had to say: I'm feeling okay this week, riding the wave of the situation. I feel normal. I don't really feel like I'm in a state of shock anymore. This feels like the new normal so I accept this type of living as my life. I am feeling the stress more and more each week. Feeling a bit uninspired these days. Looking forward to recharge this summer and do new things. A Zoom yoga instructor said to one of our staff this week, "When there's no normal, there's no abnormal." This seems to capture how a lot of us are doing8 weeks into being at home. It can be hard to even articulate how we feel or how we are doing. Compared to what? Based on what criteria? Looking at the results from the Student Survey this week, we know that many of you are experiencing significant changes to what was once your normal. In these abnormal times, we want to stress that there are resources out there to support you and we are all in this together. -

Bayonne, NJ Call 201-339-7593 Ad Pg

SUPER SPIN Hudson FREE Performance LAUNDROMAT Kebab Page 2 Page 5 Page 12 Page 16 TV 45th Year DOUBLE ISSUE Aug. 28 - Sept. 10, 2021 WOMAN OWNED www.TVTALKMAG.com Call 917-232-5501 Dry Cleaning & Shirt Laundry 1089 Ave. C (cor. of 53rd St.) Bayonne, NJ Call 201-339-7593 Ad Pg. 5 Story Pg. 11 942 Broadway, Bayonne, NJ PIERO’S (cor. of 45th St.) SCHOOL OF MUSIC Call Now 201-437-3220 SIGN UP NOW FOR BACK TO SCHOOL CLASSES Hurry don’t Be Late Classes Are Filling Up Fast! from revealing the truth. Wait to See: ARIES - Mar 21/Apr 20 Everyone rec- adopting a fresh perspective may help you see things more clearly. Ben surprises Ciara with an impromptu SAGITTARIUS-Nov 23/Dec 21 Sagittarius, try doing something on the wedding. Claire bids farewell to ognizes your ambition this week, Aries. Channel your energy constructively and don't be ashamed to pursue your goals so strongly. spur of the moment. Spotaneity may give you a rush that you may not Salem. EJ tries to enlist Nicole’s help. TAURUS - Apr 21/May 21 Taurus, tackle some slow and steady work this have felt in some time. This could be just the excitement you need right GENERAL HOSPITAL Spencer’s week rather than trying to be innovative or unique. There will be a time to now. party turned out to be more than he innovate later on. Right now you need to prove yourself. CAPRICORN- Dec 22/Jan 20 Try to meet some new people, Capricorn. -

NYSE Reopens with 25% of Staff, 'Some Good News' Acquisition

DAILY SCOOP NYSE reopens with 25% of staff, ‘Some Good News’ acquisition takes heat, and Pizza Hut celebrates grads Also: The majority of publications continue to focus on COVID-19 news, Disney World shares recipe for popular resort treat, Hy-Vee hands out masks in Iowa, and more. By Beki Winchel @bekiweki May 26, 2020 LinkedIn Twitter Facebook More Hello, communicators: Pizza Hut is celebrating this year’s graduates with free pizzas. Eligible consumers can claim a medium one-topping pizza as part of a partnership with America’s Dairy Farmers giving away 500,000 pies: PizzaHut @pizzahut Congratulations Class of 2020, you did it! Together with America’s dairy farmers, we want to celebrate all your accomplishments with half a million FREE pizzas. Visit bit.ly/2ynfRE0 to claim your free medium 1-topping pizza while supplies last. 1,147 11:46 PM - May 21, 2020 694 people are talking about this DFA @dfamilk Help get the word out. Share with the graduate in your life! twitter.com/DairyGood/stat… Dairy Good @DairyGood ICYMI: @FallonTonight announced a partnership between America’s dairy farmers and @pizzahut! See how you can make graduation weekend undeniably unforgettable! #UndeniablyDairy pizzahut.com/gradparty Check out the segment at 7:29 of this clip: bit.ly/36tQFZ9 21 2:21 PM - May 22, 2020 See DFA's other Tweets The move exempliˆes a branding effort meant to keep an organization top- of-mind, while also racking up goodwill generated by a CSR effort and partnership during COVID-19. If you’re still searching for ways to help out the community, go deeper than a donation. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of Communications the RISE and FALL of GRANTLAND a Thesis in Medi

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications THE RISE AND FALL OF GRANTLAND A Thesis in Media Studies by Roger Van Scyoc © 2018 Roger Van Scyoc Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2018 The thesis of Roger Van Scyoc was reviewed and approved* by the following: Russell Frank Associate Professor of Journalism Thesis Adviser Ford Risley Professor of Journalism Associate Dean for Undergraduate and Graduate Education Kevin Hagopian Senior Lecturer of Media Studies John Affleck Knight Chair in Sports Journalism and Society Matthew McAllister Professor of Media Studies Chair of Graduate Programs *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT The day before Halloween 2015, ESPN pulled the plug on Grantland. Spooked by slumping revenues and the ghost of its ousted leader Bill Simmons, the multimedia giant axed the sports and pop culture website that helped usher in a new era of digital media. The website, named for sports writing godfather Grantland Rice, channeled the prestige of a bygone era while crystallizing the nature of its own time. Grantland’s writers infused their pieces with spry commentary, unabashed passion and droll humor. Most importantly, they knew what they were writing about. From its birth in June 2011, Grantland quickly became a hub for educated sports consumption. Grantland’s pieces entertained and edified. Often vaulting over 1,000 words, they also skewed toward a more affluent and more educated audience. The internet promoted shifts and schisms by its very nature. Popular with millennials, Grantland filled a certain niche.