Managing Risk to Avoid Supply-Chain Breakdown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCCUPATIONAL MEDICINE PROGRAM HANDBOOK October 2005

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OFFICE OF OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY OCCUPATIONAL MEDICINE PROGRAM HANDBOOK October 2005 This Occupational Medicine Program Handbook was prepared by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Office of Occupational Health and Safety, in consultation with the U.S. Office of Personnel Management and the U.S. Public Health Service’s Federal Occupational Health service. This edition of the Handbook represents the continuing efforts of the contributing agencies to improve occupational health services for DOI employees. It reflects the comments and suggestions offered by users over the years since it was first introduced, and addresses the findings, concerns, and recommendations summarized in the final report of a program review completed in 1994 by representatives of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. That report, entitled “A Review of the Occupational Health Program of the United States Department of the Interior,” was prepared by Margaret A.K. Ryan, M.D., M.P.H., Gail Gullickson, M.D., M.P.H., W. Garry Rudolph, M.D., M.P.H., and Elizabeth Odell. The report led to the establishment of the Department’s Occupational Health Reinvention Working Group, composed of representatives from the DOI bureaus and operating divisions. The recommendations from the Reinvention Working Group final report, published in May of 1996, were addressed and are reflected in what became this Handbook. First published in 1997, the Handbook underwent a major update in July, 2000. This 2005 version of the Handbook incorporates the updates and enhancements that have been made in DOI policies and occupational medicine practice since the last edition. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 97/Monday, May 20, 2019/Proposed Rules

22756 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 97 / Monday, May 20, 2019 / Proposed Rules rents, or royalties received or accrued (iii) Anti-abuse rule. Paragraphs § 1.958–2 Constructive ownership of from a foreign corporation as received or (f)(2)(iv)(B)(1) and (3) of this section stock. accrued from a controlled foreign apply to taxable years of controlled * * * * * corporation payor if a principal purpose foreign corporations ending on or after (d) * * * of the use of an option to acquire stock May 17, 2019, and to taxable years of (1) * * * Except as otherwise or an equity interest, or an interest United States shareholders in which or provided in paragraph (d)(2) of this similar to such an option, that causes with which such taxable years end, with section and § 1.954–1(f)— the foreign corporation to be a respect to amounts that are received or * * * * * controlled foreign corporation payor is accrued by a controlled foreign (e) * * * Except as otherwise to qualify dividends, interest, rents, or corporation on or after May 17, 2019 to provided in § 1.954–1(f), if any person royalties paid by the foreign corporation the extent the amounts are received or has an option to acquire stock, such for the section 954(c)(6) exception. For accrued in advance of the period to stock shall be considered as owned by purposes of this paragraph which such amounts are attributable such person. * * * (f)(2)(iv)(B)(2), an interest that is similar with a principal purpose of avoiding the * * * * * to an option to acquire stock or an application of paragraph (f)(2)(iv)(B)(1) (h) Applicability date. -

2010 Ca-1 Tutorial Textbook

Name:_______________________ 2010 CA-1 TUTORIAL TEXTBOOK 4th Edition STANFORD UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER DEPARTMENT OF ANESTHESIOLOGY Aileen Adriano, M.D. KtKate EllbEllerbroc k, MDM.D. Becky Wong, M.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………….ii Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………….iii Contributors…………………………………………………………………….iv Key Points and Expectations…………………………………………………...v Goals of the CA-1 Tutorial Month……………………………………………..vi Checklist for CA-1 Mentorship Intraoperative Didactics………………………vii CA-1 Mentorship Intraoperative Didactic Lectures Standard Monitors………………………………………………..1 Inhalational Agents…………………………………………….....4 MAC and Awareness……………………………………………..7 IV Induction Agents……………………………………………..10 Rational Opioid Use……………………………………………..13 Intraoperative Hypotension & Hypertension……………………16 Neuromuscular Blocking Agents………………………………..19 Difficult Airway Algorithm……………………………………..23 Fluid Management ……………………………………………...27 Transfusion Therapy…………………………………………….31 Hypoxemia…………………………………………………........35 Electrolyte Abnormalities……………………………………….39 Hypothermia & Shivering………………………………….……44 PONV……………………………………………………………47 Extubation Criteria & Delayed Emergence……………….….…50 Laryngospasm & Aspiration…………………………………….53 Oxygen Failure in the OR……………………………………….56 Anaphylaxis……………………………………………………..59 ACLS…………………………………………………….………62 Malignant Hyperthermia………………………………………...65 Perioperative Antibiotics………………………………………..69 Cognitive Aids Reference Slides………………………………..72 i INTRODUCTION TO THE CA-1 TUTORIAL MONTH We want to welcome you as the -

Redundancy Unite Guide for Members Contents

Legal services Right by your side Redundancy Unite guide for members Contents Introduction 3 What is redundancy? 4 Lay-off and short term working Consultation 5 Re-structures and changes to terms and conditions When should consultation begin? Disclosure of information Scope of Consultation Requirement to complete the HR1 form Insolvency Failure to inform and consult Protective Award Representative’s role 8 Time off for representatives Facilities for representatives Statutory protection for representatives Selection for redundancy 9 Discrimination Automatically unfair selection criteria Notice 11 Time off to look for work Redundancy pay 12 Workers with no right to redundancy pay Calculating redundancy pay A ‘weeks’ pay Written statement Redundancy payments and tax State benefits Alternative employment 14 Maternity Leave Trial period Unfair dismissal Time limit COVID 19 16 Corona Virus Job Retention Scheme Section 188 consultation Selection for Redundancy Calculation of Statutory Redundancy Pay Calculation of Statutory Notice Pay Introduction Redundancy has become an all too depressing feature of the modern economic landscape. Globalisation, increased competition, technological change, government cuts have all contributed to the continuing tide of job losses. At least 109,000 workers lost their jobs in the UK through redundancy in 2019. Redundancy affects not only individuals, but their families and local communities as well. For this reason Unite seeks to use all means possible to safeguard jobs. Our aim is always to reach agreements which -

Complementarity in Public Health Systems: Using Redundancy As a Tool of Public Health Governance

Annals of Health Law Volume 22 Issue 2 Special Edition 2013 Article 4 2013 Complementarity in Public Health Systems: Using Redundancy as a Tool of Public Health Governance Lance Gable Benjamin Mason Meier Follow this and additional works at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/annals Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons Recommended Citation Lance Gable & Benjamin M. Meier Complementarity in Public Health Systems: Using Redundancy as a Tool of Public Health Governance, 22 Annals Health L. 224 (2013). Available at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/annals/vol22/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Annals of Health Law by an authorized editor of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact law- [email protected]. Gable and Meier: Complementarity in Public Health Systems: Using Redundancy as a T Complementarity in Public Health Systems: Using Redundancy as a Tool of Public Health Governance Lance Gable* & Benjamin Mason Meier** I. INTRODUCTION Modem notions of public health law embody an astounding complexity. Layers of authority arise from the accretion of legislative, regulatory, and common law developments over many years and across many subjects and jurisdictions.' As recognition of the variety and interconnectedness of public health threats has grown to encompass both proximal and distal determinants of health, the application and relevance of law has evolved to address these challenges.2 Traditional understandings of public health law focused primarily on alleviation -

Hazard Analysis Fail-Safe Design Redundancy

Fact Sheet #15 – December 2020 Revision: Five (Sample Posting Below with Downloadable Copy at the bottom of the document) Northeastern University Procedure For Running Unattended Equipment And Experiments Background Equipment and experiments that run unattended during the day and overnight have the potential of causing significant problems and harm to University personnel, facilities, and equipment. Although we discourage this practice as much as possible, particularly when hazardous substances are involved, we do recognize there is a need to run these experiments at certain times. The following procedures should be used as guidance when carrying out such experiments. Hazard Analysis Anyone considering running an experiment unattended should consider the possible hazards that could occur as a result of failures, malfunctions, operational methods, environments encountered, maintenance error and operator error. These hazards can be identified by looking at the system as a whole and identifying which failure(s) could occur. Some examples include: a) Water If water was suddenly interrupted or a hose pulled out or burst, would the system overheat, flood the laboratory, or cause some other problem? b) Signage If appropriate signage was not used, could someone mistake the containers or turn a switch that was intended to remain open/closed? c) Power Interruption If power was suddenly interrupted would the system or safety features for the system also be shut down? Fail-Safe Design Experiments must be designed so that they are “fail-safe”, which means that they will prevent one malfunction from propagating other failures. Fail-safe designs ensure that a failure will leave the experiment unaffected or will convert it to a state in which no injury or damage will occur. -

Hazard Control Selection and Management Requirements

ENVIRONMENT, SAFETY & HEALTH DIVISION Chapter 1: General Policy and Responsibilities Hazard Control Selection and Management Requirements Product ID: 671 | Revision ID: 1744 | Date published: 27 May 2015 | Date effective: 27 May 2015 URL: http://www-group.slac.stanford.edu/esh/eshmanual/references/eshReqControls.pdf 1 Purpose This document defines how a risk-based approach is used to determine the need for controls on facilities, systems, or components to protect the public, workers, and the environment. For controls necessary to prevent or mitigate serious events, specific devices and procedures will be formally credited as part of the approved safety envelope. How these controls are selected, evaluated, and approved, and the process for maintaining and modifying controls, are described in these requirements1. As used here, controls and hazard controls mean those engineered, administrative, or personal protective elements that are used to protect against a hazard. Normal process or operational controls are not included in these requirements except to the extent that their use is directly tied to safety. The concept of credited control is well established in the accelerator safety community. The concept of credited control is borrowed from DOE Order 420.2C, “Safety of Accelerator Facilities” (DOE O 420.2C), but this document neither extends the requirements of DOE O 420.2C to non-accelerator hazards nor modifies those requirements for accelerator hazards. The intent is to extend those robust principles to management of controls for non-accelerator hazards of similar risk. 2 Roles and Responsibilities 2.1 Associate Laboratory Director . Ensures that technical systems under his or her directorate’s management are properly analyzed to determine the type and level of controls necessary to control risk to an acceptable level . -

Redundancy, Business Flexibility and Workers' Security: Findings of A

International Labour Review, Vol. 140 (2001), No. 1 Redundancy, business flexibility and workers’ security: Findings of a comparative European survey Marie-Laure MORIN * and Christine VICENS ** ll over Europe, the past 20 years have seen profound changes in labour A markets, together with high levels of structural unemployment and growing insecurity. These developments bear witness to the persistent con- flict between an economic rationale — calling for ever-greater business flexibility — and a social rationale demanding a certain degree of job security for workers. Labour market flexibility is generally measured primarily in terms of the impact of employment protection legislation. Some authors consider that legislation hardly affects employment or unemployment in absolute terms (Freyssinet, 2000); others regard it as playing a part in inter-country dis- parities in these respects and emphasize the possible links between the strin- gency of employment protection provisions and the extent of labour turnover, on the one hand, and the average duration of unemployment, on the other (OECD, 1996). Others, again, argue in favour of rethinking the indicators used to measure the effects of employment protection legislation on levels of unemployment, in the light of enforcement procedures and the links between employment protection 1 and other labour market institutions (Bertola, Boeri and Cazes, 2000). In exploring ways of reconciling enterprise flexibility and job security, existing work reflects an obvious dichotomy between corporate management issues — i.e. research into changes in the production system, such as corporate 1 *Research director and studies engineer at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). **Studies engineer at the Interdisciplinary Research Laboratory for Human Resources and Employment (LIRHE), University of Toulouse I. -

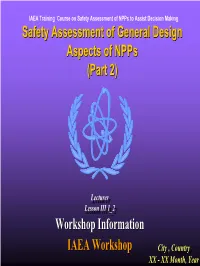

Safety Assessment of General Design Aspects of Npps (Part 2)

IAEA Training Course on Safety Assessment of NPPs to Assist Decision Making SafetySafety AssessmentAssessment ofof GeneralGeneral DesignDesign AspectsAspects ofof NPPsNPPs (Part(Part 2)2) LecturerLecturer LessonLesson III III 1_2 1_2 WorkshopWorkshop InformationInformation IAEAIAEA WorkshopWorkshop CityCity , ,Country Country XXXX - - XXXX Month, Month ,Year Year ItemsItems forfor DiscussionDiscussion z Review of Single Failure Criterion z System Redundancy z System Independence z System Diversity z Concept of Fail-Safe Design z System Interactions and Dependencies z Conduct of Single Failure Assessments IAEA Training Course on Safety Assessment of NPPs to Assist Decision Making 2 ReviewReview ofof SingleSingle FailureFailure CriteriaCriteria z “.. protection system shall be designed for high functional reliability and inservice testability commensurate with safety functions performed.” z “Redundancy and independence designed into protection system shall be sufficient to assure: z “1. No single failure results in the loss of protective function..” z “2. Removal from service of any component or channel does not result in loss of required minimum redundancy unless acceptable reliability of operation of protection system can be otherwise demonstrated.” IAEA Training Course on Safety Assessment of NPPs to Assist Decision Making 3 ReviewReview ofof SingleSingle FailureFailure CriteriaCriteria z “..protection system shall be designed to permit periodic testing of its functioning when reactor is in operation, including a capability to test channels -

Evacuation Transportation Management Operational Concept

Evacuation Transportation Management Task Five: Operational Concept Prepared for: Federal Highway Administration Produced in collaboration with the Intelligent Transportation System Joint Program Office June 26, 2006 Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the department of transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade and manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the object of the document. 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA-HOP-08-020 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Operational Concept June 2006 Assessment of the State of the Practice and State of the Art in 6. Performing Organization Code Evacuation Transportation Management 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Pierre Pretorius, Susan Anderson, Kwasi Akwabi, Brent Crowther, Queenie Ye, Nancy Houston, Andrea Vann Easton 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. 7878 N. 16th Street, Suite 300 11. Contract or Grant No. Phoenix, Arizona 85020 Booz Allen Hamilton 8283 Greensboro Drive McLean, Virginia 22102 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Federal Highway Administration Final Report U.S. Department of Transportation 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE HOTO, FHWA Washington, DC 20590 15. Supplementary Notes Kimberly Vasconez, FHWA, Office of Operations, Contracting Officer’s Technical Representative (COTR). Document was prepared by Booz Allen Hamilton under contract to FHWA. -

Effective Usage of Redundancy and Flexibility in Resilient Supply Chains

Effective Usage Of Redundancy And Flexibility In Resilient Supply Chains Vlajic, J. (2017). Effective Usage Of Redundancy And Flexibility In Resilient Supply Chains. In KS. Pawar, A. Potter, & A. Lisec (Eds.), Proceedings of the 22nd International Symposium on Logistics (ISL 2017): Data Driven Supply Chains (pp. 450-458). Centre for Concurrent Enterprise, Nottingham University Business School. Published in: Proceedings of the 22nd International Symposium on Logistics (ISL 2017): Data Driven Supply Chains Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2017 Nottingham University Business School. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. javascript:void(0); General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:27. Sep. 2021 EFFECTIVE USAGE OF REDUNDANCY AND FLEXIBILITY IN RESILIENT SUPPLY CHAINS Jelena V. -

Intrinsic Redundancy for Reliability and Beyond

Intrinsic Redundancy for Reliability and Beyond Alberto Goffi, Alessandra Gorla, Andrea Mattavelli, and Mauro Pezze` Abstract Software redundancy is an essential mechanism in engineering. Different forms of redundant design are the core technology of well-established reliability and fault tolerant mechanisms in traditional engineering as well as in software engineering. In this paper we discuss intrinsic software redundancy, a type of redundancy that is not added explicitly at design time to improve runtime reliability, but is natively present in modern software system due to independent design and development decisions. We introduce the concept of intrinsic redundancy, discuss its diffusion and the reasons for its presence in modern software systems, indicate how it can be automatically identified, and present some current and future applications of such form of redundancy to produce more reliable software systems at affordable costs. 1 Introduction Reliability, which is the ability of a system or component to perform its required functions under stated conditions for a specified period of time [1], is a key property of engineered products and in particular of software artifacts. Safety critical applications must meet the high reliability standards required for their field deployment, time- and business-critical applications must obey strong reliability requirements, everyday Alberto Goffi USI Universita` della Svizzera italiana, Switzerland, e-mail: alberto.goffi@usi.ch Alessandra Gorla IMDEA Software Institute, Spain, e-mail: [email protected] Andrea Mattavelli Imperial College London, United Kingdom, e-mail: [email protected] Mauro Pezze` USI Universita` della Svizzera italiana, Switzerland and University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy, e-mail: [email protected] 1 2 Alberto Goffi, Alessandra Gorla, Andrea Mattavelli, and Mauro Pezze` and commodity products shall meet less stringent, but still demanding customer requirements.