The Dynamics of Agenda-Setting: the Case of Post-Secondary Education in Manitoba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba

FourthSess ion -Thirty-Fifth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba STANDING COMMITTEE on LAW AMENDMENTS 42 Elizabeth II Chairperson Mr. Bob Rose Constituencyof Turtle Mountain VOL XLII No.7· 9 a.m., THURSDAY, JULY 8, 1993 ISSN0713-9586 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thirty-Fifth Legislature Members,Constituencies and Political Affiliation NAME CONSTITUENCY PARTY. ALCOCK, Reg Osborne Liberal ASHTON, Steve Thompson NDP BARRETT, Becky Wellington NDP CARSTAIRS, Sharon River Heights Liberal CERILLI, Marianne Radisson NDP CHOMIAK, Dave Kildonan NDP CUMMINGS, Glen, Hon. Ste. Rose PC DACQUAY, Louise Seine River PC DERKACH, Leonard, Hon. Roblin-Russell PC DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk NDP DOER, Gary Concordia NDP DOWNEY, James, Hon. Arthur-Virden PC DRIEDGER, Albert, Hon. Steinbach PC DUCHARME, Gerry, Hon. Riel PC EDWARDS, Paul St. James liberal ENNS, Harry, Hon. Lakeside PC ERNST, Jim, Hon. Charleswood PC EVANS, Clif Interlake NDP EVANS, Leonard S. Brandon East NDP FILMON, Gary, Hon. Tuxedo PC FINDLAY, Glen, Hon. Springfield PC FRIESEN, Jean Wolseley NDP GAUDRY, Neil St. Boniface Liberal GILLESHAMMER, Harold, Hon. Minnedosa PC GRAY, Avis Crescentwood Liberal HELWER, Edward R. Gimli PC HICKES, George Point Douglas NDP LAMOUREUX, Kevin Inkster Liberal LATHLIN, Oscar The Pas NDP LAURENDEAU, Marcel St. Norbert PC MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood NDP MANNESS, Clayton, Hon. Morris PC MARTINDALE, Doug Burrows NDP McALPINE, Gerry Sturgeon Creek PC McCRAE, James, Hon. Brandon West PC MciNTOSH, Linda, Hon. Assiniboia PC MITCHELSON, Bonnie, Hon. River East PC ORCHARD, Donald, Hon. Pembina PC PALLISTER, Brian Portage Ia Prairie PC PENNER, Jack Emerson PC PLOHMAN, John Dauphin NDP PRAZNIK, Darren, Hon. Lac du Bonnet PC REID, Daryl Transcona NDP REIMER, Jack Niakwa PC RENDER, Shirley St. -

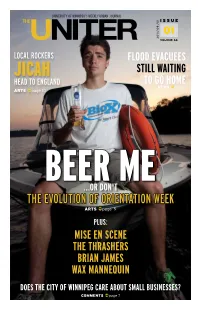

The Evolution of Orientation Week

/01 01 2011 / 09 volume 66 l ocal rockers Flood evacuees Jicah still waiting head To england to go home newS page 3 arts page 10 Beer me ...or don't The evoluTion of orienTaTion Week ARTS page 9 plus: mise en scene the thrashers brian James wax mannequin does the city oF winnipeg care about small businesses? COMMenTS page 7 02 The UniTer September 1, 2011 www.UniTer.ca Looking for Listings? c over image CAMpuS & COMMunITY LISTInGS AnD VOLunTeeR OppORTunITIeS pAGe 5 PHOTO BY DYLAN HEWLETT i s the wesmen athletic program " with so many beer choices to MuSIC pAGe 10 Dylan is The Uniter's photo expanding too rapidly? sample from, how can i say no?" FILM & LIT pAGe 13 editor for 2011/2012. GALLeRIeS & MuSEUMS pAGe 13 See more of his work at THeATRe, DAnCe & COMeDY pAGe 13 www.hewlettphotography.ca campuS newS page 6 comments page 7 AwARDS & FInAnCIAL AID pAGe 14 Quebec medical residents could strike Sept. 12 UNITER STAFF First-year residents in Quebec stand to make ManaGinG eDitor $41,000 a year, and can make around $65,000 Aaron Epp » [email protected] by their sixth or seventh year. As well, residents BSUSineS ManaGer in Quebec work on average 66 hours a week, Geoffrey Brown » [email protected] according to the results of a survey of FMRQ members. PrODUcTiOn ManaGer Ayame Ulrich [email protected] Residents suspended teaching to medical stu- » dents on July 11 as a pressure tactic. c TOPy anD S yLe eDitor While medical students have said they sup- Britt Embry » [email protected] port the residents' side of the debate, many say Photo eDitor they don't agree with their methods, out of fear Dylan Hewlett » [email protected] that their education is being jeopardized. -

Gary Albert Filmon, (MLA-Tuxedo) - President of the Executive Council; Minister of Federal/Provincial Relations' Minister of French Language Services

- THE MANITOBA CABINET January 1992 , Here is the full cabinet structure in order of precedence: Gary Albert Filmon, (MLA-Tuxedo) - President of the Executive Council; Minister of Federal/Provincial Relations' Minister of French Language Services. , - Harry John Enns, (MLA-Lakeside) - Minister of Natural Resources; Minister responsible for The Manitoba Natural Resources Development Act (except _ with respect to Channel Area Loggers Ltd. and Moose Lake Loggers Ltd.) James Erwin Downey, (MLA-Arthur-Virden) 7 Deputy Premier; Minister of Energy and Mines;, Minister responsible for the Manitoba .Hydro Act; Minister of Northern Affairs; Minister responsible for NativeAffairs, The Manitoba Natural Resources Development ACt:(with resiDect to Channel Area Loggers Ltd. and Moose Lake Loggers Ltd.), A.E.,,McKenzie Co. Ltd. , . - and The Manitoba Oil and Gas Corporation Act; Minister 'responsible for 4 and charged with the administration of the Communities _Economic• Development Fund Act. Donald Warder Orchard, (MLA-Pembina - Minister of Health. Albert Driedger, (MLA-Steinbach) Minister of Highways Transportation. Clayton Sidney Manness, (MLA-Morris) -,Minister of Finance; Government - tSCAUZ 1. ft ki4't House Leader; Minister responsible for the,administration of The Crown Corporation Accountabil ity Act; Minister Kesponsible,for.and charged. with _ , 04118 the administration of The Manitoba Data,Seryices Act 'James Glen Cummings, (MLA-Ste.:Rose Arndi.iihment;,minister charged with the 'administration of The 'Manitoba Public'Insurance „ — • Corporation Act and The Jobs Fund Act. t 4 ...... Co, James Collus McCrae, (MLA-Brandon West) -Minister of Justice and Attorney General; Keeper of The Great Seal; Minister responsible for Constitutional Affairs, Corrections, The Corrections Act (except Part II). -

Standing Committee on Legislative Affairs

Third Session - Thirty-Eighth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba Standing Committee on Legislative Affairs Chairperson Mr. Daryl Reid Constituency of Transcona Vol. LVI No. 1 - 10 a.m., Thursday, December 2, 2004 ISSN 1708-668X MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thirty-Eighth Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation AGLUGUB, Cris The Maples N.D.P. ALLAN, Nancy, Hon. St. Vital N.D.P. ALTEMEYER, Rob Wolseley N.D.P. ASHTON, Steve, Hon. Thompson N.D.P. BJORNSON, Peter, Hon. Gimli N.D.P. BRICK, Marilyn St. Norbert N.D.P. CALDWELL, Drew Brandon East N.D.P. CHOMIAK, Dave, Hon. Kildonan N.D.P. CULLEN, Cliff Turtle Mountain P.C. CUMMINGS, Glen Ste. Rose P.C. DERKACH, Leonard Russell P.C. DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk N.D.P. DOER, Gary, Hon. Concordia N.D.P. DRIEDGER, Myrna Charleswood P.C. DYCK, Peter Pembina P.C. EICHLER, Ralph Lakeside P.C. FAURSCHOU, David Portage la Prairie P.C. GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Lib. GOERTZEN, Kelvin Steinbach P.C. HAWRANIK, Gerald Lac du Bonnet P.C. HICKES, George, Hon. Point Douglas N.D.P. IRVIN-ROSS, Kerri Fort Garry N.D.P. JENNISSEN, Gerard Flin Flon N.D.P. JHA, Bidhu Radisson N.D.P. KORZENIOWSKI, Bonnie St. James N.D.P. LAMOUREUX, Kevin Inkster Lib. LATHLIN, Oscar, Hon. The Pas N.D.P. LEMIEUX, Ron, Hon. La Verendrye N.D.P. LOEWEN, John Fort Whyte P.C. MACKINTOSH, Gord, Hon. St. Johns N.D.P. MAGUIRE, Larry Arthur-Virden P.C. MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood N.D.P. MARTINDALE, Doug Burrows N.D.P. -

School Division/District Amalgamation in Manitoba

SCHOOL DIVISION/DISTRICT AMALGAMATION IN MANITOBA: A CASE STUDY OF A PUBLIC POLICY DECISION BY DAVID P. YEO A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Educational Administration, Foundations and Psychology University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba © David P. Yeo, April 2008 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract . v Acknowledgements . vii Timeline of Study . viii List of Tables . ix List of Figures . x Prologue . xi Chapter 1. PURPOSE AND NATURE OF THE STUDY. 1 Purpose of the Study . 1 Significance of the Study . 4 Theoretical Framework . 7 The Study of a Public Policy Decision: Key Concepts . 7 Public policy . 8 Politics . 11 Policy making . 16 “Beyond the Stages Heuristic”: Agenda Setting, Convergence and the Policy Window . 22 Problems . 28 Solutions (policies) . 29 Politics . 29 Policy Window . 32 Data Sources . 33 Limitations of the Study . 36 Organization of the Dissertation . 40 2. HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE STUDY . 43 School District Consolidation: 1890-1967 . 45 The Roots of Amalgamation: 1970-1999 . 57 The Boundaries Review Commission: 1993-1995 . 79 Summary and Postscript . 86 iii 3. DIRECTED AMALGAMATION DECLINED: 1996-1999 . 89 Policy . 91 The Politics of Policy Choice . 101 Considering Norrie: A Roadmap to Nowhere? . 101 Rejecting Norrie: Amalgamation if Necessary, But Not Necessarily Amalgamation . 118 Summary and Postscript . 125 4. DIRECTED AMALGAMATION ADOPTED: 1999-2002 . 128 Policy . 129 The Politics of Policy Choice . 137 Reconsidering Norrie . 137 The Norrie Plan Modified . 139 Amalgamation Rationale, Strategy and Scope . 147 Amalgamation is Necessary, But Not Necessarily Amalgamation for Everyone . -

THE MANITOBA CABINET� February 1991

THE MANITOBA CABINET February 1991 Here is the full cabinet structure in order of precedence: Gary Albert Filmon, (MLA-Tuxedo) - President of the Executive Council; Minister of Federal/Provincial Relations; Minister of French Language Services. Harry John Enns, (MLA-Lakeside) - Minister of Natural Resources; Minister responsible for The Manitoba Natural Resources Development Act (except with respect to Channel Area Loggers Ltd. and Moose Lake Loggers Ltd.) James Erwin Downey, (MLA-Arthur-Virden) - Deputy Premier; Minister of Rural Development; Minister of Northern Affairs; Minister responsible for Native Affairs, The Manitoba Natural Resources Development Act (with respect to Channel Area Loggers Ltd. and Moose Lake Loggers Ltd.), A.E. McKenzie Co. Ltd. and The Manitoba Oil and Gas Corporation Act; Minister responsible for and charged with the administration of the Communities Economic Development Fund Act. Donald Warder Orchard, (MLA-Pembina) - Minister of Health. Albert Driedger, (MLA-Steinbach) - Minister of Highways and Transportation. Clayton Sidney Manness, (MLA-Morris) - Minister of Finance; Government House Leader; Minister responsible for the administration of The Crown Corporation Accountability Act; Minister responsible for and charged with the administration of The Manitoba Data Services Act. James Glen Cummings, (MLA-Ste. Rose) - Minister of Environment; Minister charged with the administration of The Manitoba Public Insurance Corporation Act and The Jobs Fund Act. James Collus McCrae, (MLA-Brandon West) - Minister of Justice and Attorney General; Keeper of The Great Seal; Minister responsible for Constitutional Affairs, Corrections, The Corrections Act (except Part II). - 2 - MANITOBA CABINET James Arthur Ernst, (MLA-Charleswood) - Minister of Urban Affairs; Minister of Housing. Glen Marshall Findlay, (MLA-Springfield) - Minister of Agriculture; Minister responsible for the administration of the Manitoba Telephone Act. -

MB PL 2007 PC En.Pdf

Our Commitment 4 Reattract young people 4 Restore our front lines 4 Reclaim our safety 4 Rejuvenate our communities 4 Refresh our environment Big Five Hugh Will Do 4 1% PST reduction 4 More cells for criminals 4 Bring back the Jets 4 Restore our ERs 4 Rejuvenate our Downtown Message from Hugh McFadyen: "If we can dream it,we can do it." We’ve got to give young Manitobans something to dream about. That’s why I don’t look at Manitoba as what we’re not. I look at Manitoba as what we can be. In fact, I’ve always believed that if we can dream it, we can do it. Together, we can have streets that are safe again, a city that is one of Canada’s coolest, respect for our health care professionals, communities that are not only clean but vibrant and growing, plus a way of life that keeps getting better no matter what your age or stage in life. Our plan demonstrates that we will offer Manitobans hope for the future and a reason to believe that, together, we can do better. Hugh McFadyen, Leader Progressive Conservative Party of Manitoba Table of Contents Message from Rejuvenate our communities Hugh McFadyen Winnipeg Brandon Reattract young people Rural Manitoba Cattle Industry Tax Relief Northern Manitoba Provincial Sales Tax Education K-12 Education Taxes Child Care Personal Income Taxes Aboriginal Peoples Business Taxes Arts and Culture Winnipeg Jets Immigration Post Secondary Education and Training Refresh our environment Strategy for Capital Markets Manitoba Hydro Government Accountability Conservation Districts, Drainage and Water Management Restore -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

University Autonomy and Higher Education Policy Development in Manitoba by Daniel William Smith A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Individual Interdisciplinary Program University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2008 by Daniel William Smith Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-50452-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-50452-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

News Service Phone: (204) 945-3746 R3C OV8 Date: May 13, 1988� (9

Information Services Room 29 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba, CANADA News Service Phone: (204) 945-3746 R3C OV8 Date: May 13, 1988 (9- FIL4ON ADMINISTRATION INSTALLED INTO OFFICE - - - Lt. Gov. Swears In 16 Cabinet Ministers Premier Gary Filmon and 15 Manitoba Progressive Conservative M.L.A.s were sworn in May 9 as members of the new administration's Executive Council. During the swearing -in ceremony, conducted by Lieutenant-Governor George Johnson, Premier Filmon said there are few experiences in life more humbling than being called to serve as a member of the Executive Council. "But it is also a responsibilty," he said, "and one which cannot be taken lightly. It is a responsibility that is about much more than just good bookkeeping. It is about providing a legacy for our children." Filmon said his government is taking office at a challenging time in the province's history and he renewed his commitment to building an open and responsible administration. The Filmon cabinet, in order of precedence, follows: Gary Albert Filmon, (MLA-Tuxedo) - President of the Executive Council; Minister of Federal-Provincial Relations; Chairman of the Treasury Board. James Erwin Downey, (MLA-Arthur) - Minister of Northern Affairs; Minister responsible for Native Affairs; Minister responsible for the Communities Economic Development Fund Act; Minister responsible for the Channel Area Loggers Limited; Minister responsible for Moose Lake Loggers Limited; Minister responsible for A.E. MacKenzie Company Limited; Minister responsible for Manitoba Oil and Gas Corporation. Donald Warder Orchard, (MLA-Pbmbina) - Minister of Health. Albert Driedger, (MLA-Emerson) - Minister of Highways and Transportation; Minister of Government Services. -

School Division/District Amalgamation in Manitoba: a Case Study of a Public Policy Decision

SCHOOL DIVISION/DISTRICT AMALGAMATION IN MANITOBA: A CASE STUDY OF A PUBLIC POLICY DECISION BY DAVID P. YEO A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Educational Administration, Foundations and Psychology University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba © David P. Yeo, April 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-41282-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-41282-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation.