Spottiswoode-Etal-2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Ghana

Avibase Page 1of 24 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Ghana 2 Number of species: 773 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 26 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2019-11-10 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Ghana. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=gh [26/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Notes on Honeyguides in Southeast Cape Province, South Africa

52 SK•AD,Honeyguides ofSoutheast CapeProvince t[AukJan. NOTES ON HONEYGUIDES IN SOUTHEAST CAPE PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA BY C. J. SKEAD Now that I am no longer living on a farm it seemsadvisable to collate what little data I have accumulatedon honeyguidesand add it to the scanty knowledgewe have of these birds, in this instance the LesserHoneyguide, Indicator minor minor, the Greater Honeyguide, Indicator indicator, and Wahlberg's Sharp-billed Honeyguide, Pro- dotiscusregulus regulus. The farm "Gameston" where these records were taken lies in the grass-and bush-coveredupper reachesof the Kariega River, 15 miles southwestof Grahamstown, Albany district, Southeast Cape Province, South Africa. This veld-type, known as "bontebosveld," spreads over a large part of the southeastcape. Although I have known the birds for many years the written recordscover a period of about five years. (1) THE LESSERHONEYGUIDE F.colog3.--This speciesprefers the scrub bushyeld and more open acaciaveld, sitting amongthe inner branchesof the trees and bushes but makingconspicuous flights in the openfrom one patch of bushto another. Status.--I have recordedthem in January, February, March, July, August,September, and December. This suggeststhey are resident and not migratory. They are very restlessbirds being seldomseen for more than an hour or so and, in my experience,usually one at a time, even when they parasitized a nest of Black-collared Barbers, Lybius torquatus,in our garden. But from July to September, 1949, two often consortedtogether, attracted, I think, by combs of honey protrudingfrom the gardenbee-hives. There were no barbetsin the garden then. Field Characters.--Thereare no striking features; their dull colora- tion is lightly offset by the golden sheen seen on the back when the light is good. -

The Gambia in Style

The Gambia in Style Naturetrek Tour Report 7 - 14 December 2018 Broad-billed Roller Blue-breasted Kingfisher Western Red Colobus Little Bee-eater Report compiled by Duncan McNiven Images courtesy of Debbie Pain Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report The Gambia in Style Tour participants: Duncan McNiven and Debbie Pain (leaders) plus local guides and 12 Naturetrek clients Day 1 Friday 7th December London Gatwick to Mandina Lodge We all met up at Gatwick Airport for our mid-morning Titan Airways flight to Banjul, the capital of Gambia. Our flight was slightly delayed due to inclement weather but soon enough we were on our way south, leaving behind the mountains and plains of southern Europe and crossing the vast aridness of the Sahara Desert. Eventually, the landscape below us became greener and lusher as we crossed in to Senegal and entered the Guinea Savannah biome. By the time we touched down in Banjul it was already early evening and the light was beginning to wane. Duncan and Debbie were there to meet and greet us and help with acquiring the small amount of local currency we would require for our holiday and in no time at all we were aboard our bus for our short journey to Mandina Lodge. Less than an hour later we were sat under the twinkling fairy lights of the Mandina reception area whilst our gracious host Linda welcomed us and gave us the briefest of briefings before we were all shown to our luxurious lodges nestled amongst the mangroves and forest trees lining the river. -

Adult Brood Parasites Feeding Nestlings and Fledglings of Their Own Species: a Review

J. Field Ornithol., 69(3):364-375 ADULT BROOD PARASITES FEEDING NESTLINGS AND FLEDGLINGS OF THEIR OWN SPECIES: A REVIEW JANICEC. LORENZANAAND SPENCER G. SEALY Departmentof Zoology Universityof Manitoba Winnipeg,Manitoba R3T 2N2 Canada Abstract.--We summarized 40 reports of nine speciesof brood parasitesfeeding young of their own species.These observationssuggest that the propensityto provisionyoung hasnot been lost entirely in brood parasitesdespite the belief that brood parasiticadults abandon their offspringat the time of laying.The hypothesisthat speciesthat participatein courtship feeding are more likely to provisionyoung was not supported:provisioning of young has been observedin two speciesof brood parasitesthat do not courtshipfeed. The function of this provisioningis unknown, but we suggestit may be: (1) a non-adaptivevestigial behavior or (2) an adaptation to ensure adequatecare of parasiticyoung. The former is more likely the case.Further studiesare required to determinewhether parasiticadults commonly feed their genetic offspring. ADULTOS DE AVES PARAS•TICASALIMENTANDO PICHONES Y VOLANTONES DE SU PROPIA ESPECIE: UNA REVISION Sinopsis.--Resumimos40 informes de nueve especiesde avesparasiticas que alimenaron a pichonesde su propia especie.Las observacionessugieren que la propensividadde alimentar a los pichonesno ha sido totalmente perdida en las avesparasiticas, no empecea la creencia de que los parasiticosabandonan su progenie al momento de poner los huevos.La hipttesis de que las especiesque participan en cortejo de alimentacitn, son milspropensas a alimentar los pichonesno tuvo apoyo.Las observacionesde alimentacitn a pichonesse han hecho en dos especiesparasiticas cuyo cortejo no incluye la alimentacitn de la pareja. La funcitn de proveer alimento se desconoce.No obstante,sugerimos que pueda ser: 1) una conducta vestigialno adaptativa,o 2) una adaptacitn parc asegurarel cuidado adecuadode los pi- chonesparasiticos. -

Keeping an Eye on the Sentinel Mutualistic Relationship Between The

Keeping an eye on the sentinel Mutualistic relationship between the honeyguide bird and honey hunters Edmond Dounias IRD, UMR 5175 CEFE, 1919 route de Mende, 34293 Montpellier (France), [email protected] mo è jEE mbÈlÈkÒ y&iè pÒkì kÒ ! If you hear the honeyguide singing, honey is near! Importance of honey hunting among African Pygmies (a Baka pygmy proverb expressing evidence) Honey hunting is a prominent activity among the various groups of African Pygmies. Pygmy hunter-gatherers eagerly look forward to the taste of honey. Honey does not only provide the pleasure of eating, it also functions as a medium by which social relations are regulated. African Pygmies collect honey produced by the honey bee Apis mellifera adansonii and from a dozen different species of stingless bees. Honey harvesting is a seasonal activity that depends on the flowering season of the major nectar sources of the forest. It can be carried out almost continuously from November to June, with picks occurring in February and May. Throughout the Congo Basin, no people other than the Pygmy hunter-gatherers collect honey in such a systematic way. Collecting honey is a characteristic subsistence activity in the tropical forest. There are so many natural hollows suitable for beehive that the successful settlement of bees into artificial hives is highly hazardous. Accordingly, collecting wild honey is much more adaptive to the tropical (© Edmond Dounias) rainforest environment, thus explaining that foragers are much more adapted to other groups to carry out such activity. Birds-Pygmies interactions Whatever the latitude, humans entertain complex relationships with birds, but these interconnections have a particularly high influence on the life of forest foragers. -

Brain Size and Morphology of the Brood-Parasitic and Cerophagous Honeyguides (Aves: Piciformes)

Original Paper Brain Behav Evol Received: August 2, 2012 DOI: 10.1159/000348834 Returned for revision: September 9, 2012 Accepted after second revision: February 10, 2013 Published online: April 24, 2013 Brain Size and Morphology of the Brood-Parasitic and Cerophagous Honeyguides (Aves: Piciformes) e b a, c Jeremy R. Corfield Tim R. Birkhead Claire N. Spottiswoode e d f Andrew N. Iwaniuk Neeltje J. Boogert Cristian Gutiérrez-Ibáñez g f g Sarah E. Overington Douglas R. Wylie Louis Lefebvre a DST/NRF Center of Excellence, Percy FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town , South Africa; b c Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Sheffield , Department of Zoology, d University of Cambridge, Cambridge , and School of Biology, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews , UK; e f Department of Neuroscience, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, Alta. , Center for Neuroscience, g University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alta. , and Department of Biology, McGill University, Montreal, Que. , Canada Key Words fers greatly between honeyguides and woodpeckers. The Brain size · Brood parasitism · Hippocampus · Piciformes · relatively smaller brains of the honeyguides may be a conse- Volumetrics quence of brood parasitism and cerophagy (‘wax eating’), both of which place energetic constraints on brain develop- ment and maintenance. The inconclusive results of our anal- Abstract yses of relative HF volume highlight some of the problems Honeyguides (Indicatoridae, Piciformes) are unique among associated with comparative studies of the HF that require birds in several respects. All subsist primarily on wax, are further study. Copyright © 2013 S. Karger AG, Basel obligatory brood parasites and one species engages in ‘guid- ing’ behavior in which it leads human honey hunters to bees’ nests. -

1 Convergent Evolution of Reduced Eggshell Conductance in Avian

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Royal Holloway - Pure Convergent evolution of reduced eggshell conductance in avian brood parasites Stephanie C. McClelland1*, Gabriel A. Jamie2,3, Katy S. Waters1, Lara Caldas1, Claire N. Spottiswoode2,3 and Steven J. Portugal1 1School of Biological Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, Surrey, TW20 0EX, UK. 2Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, University of 10 Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK. 3FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, DST-NRF Centre of Excellence, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, Cape Town, South Africa. Subject Areas: evolution, parasitism, physiology Keywords: Cuculidae, eggs, gas exchange, Indicatoridae, Viduidae Author for Correspondence: Stephanie C. McClelland, email: [email protected] 20 1 Abstract Brood parasitism has evolved independently in several bird lineages, yet these species 30 share many similar physiological traits that optimise this breeding strategy, such as shorter incubation periods and thicker eggshells. Eggshell structure is important for embryonic development as it controls the flux of metabolic gases, such as O2, CO2 and H2O, into and out of the egg; in particular, water vapour conductance (GH2O) is an essential process for optimal development of the embryo. Previous work has shown that common cuckoos (Cuculus canorus) have a lower than expected eggshell GH2O compared to their hosts. Here we sought to test whether this is a trait found in other independently-evolved avian brood parasites, and therefore reflects a general adaptation to a parasitic lifestyle. We analysed GH2O for seven species of brood parasites from four unique lineages as well as for their hosts, and combined this with species 40 from the literature. -

Kruger Comprehensive

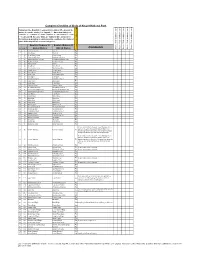

Complete Checklist of birds of Kruger National Park Status key: R = Resident; S = present in summer; W = present in winter; E = erratic visitor; V = Vagrant; ? - Uncertain status; n = nomadic; c = common; f = fairly common; u = uncommon; r = rare; l = localised. NB. Because birds are highly mobile and prone to fluctuations depending on environmental conditions, the status of some birds may fall into several categories English (Roberts 7) English (Roberts 6) Comments Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps # Rob # Global Names Old SA Names Rough Status of Bird in KNP 1 1 Common Ostrich Ostrich Ru 2 8 Little Grebe Dabchick Ru 3 49 Great White Pelican White Pelican Eu 4 50 Pinkbacked Pelican Pinkbacked Pelican Er 5 55 Whitebreasted Cormorant Whitebreasted Cormorant Ru 6 58 Reed Cormorant Reed Cormorant Rc 7 60 African Darter Darter Rc 8 62 Grey Heron Grey Heron Rc 9 63 Blackheaded Heron Blackheaded Heron Ru 10 64 Goliath Heron Goliath Heron Rf 11 65 Purple Heron Purple Heron Ru 12 66 Great Egret Great White Egret Rc 13 67 Little Egret Little Egret Rf 14 68 Yellowbilled Egret Yellowbilled Egret Er 15 69 Black Heron Black Egret Er 16 71 Cattle Egret Cattle Egret Ru 17 72 Squacco Heron Squacco Heron Ru 18 74 Greenbacked Heron Greenbacked Heron Rc 19 76 Blackcrowned Night-Heron Blackcrowned Night Heron Ru 20 77 Whitebacked Night-Heron Whitebacked Night Heron Ru 21 78 Little Bittern Little Bittern Eu 22 79 Dwarf Bittern Dwarf Bittern Sr 23 81 Hamerkop -

Southern Tanzania: Endemic Birds & Spectacular Mammals

SOUTHERN TANZANIA: ENDEMIC BIRDS & SPECTACULAR MAMMALS SEPTEMBER 18–OCTOBER 6, 2018 Tanzanian Red-billed Hornbill © Kevin J. Zimmer LEADERS: KEVIN ZIMMER & ANTHONY RAFAEL LIST COMPILED BY: KEVIN ZIMMER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM SOUTHERN TANZANIA: ENDEMIC BIRDS & SPECTACULAR MAMMALS September 18–October 6, 2018 By Kevin Zimmer After meeting in Dar es Salaam, we kicked off our inaugural Southern Tanzania tour by taking a small charter flight to Ruaha National Park, at 7,800 square miles, the largest national park in all of east Africa. The scenery from the air was spectacular, particularly on our approach to the park’s airstrip. Our tour was deliberately timed to coincide with the dry season, a time when many of the trees have dropped their leaves, heightening visibility and leaving the landscapes starkly beautiful. This is also a time when the Great Ruaha River and its many smaller tributaries dwindle to shallow, often intermittent “sand rivers,” which, nonetheless, provide natural game corridors and concentration points for birds during a time in which water is at a premium. Bateleur, Ruaha National Park, Sept 2018 (© Kevin J. Zimmer) After touching down at the airstrip, we disembarked to find our trusty drivers, Geitan Ndunguru and Roger Mwengi, each of them longtime friends from our Northern Tanzania tours, waiting for us with their safari vehicles ready for action. The first order of business was to head to the lodge for lunch, but a large, mixed-species coven of Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 Southern Tanzania, 2018 vultures could not be ignored, particularly once we discovered the reason for the assemblage—a dead Hippo, no doubt taken down the previous night as it attempted to cross from one river to another, and, the sated Lion that had been gorging itself ever since. -

Assessment of Farming Systems and Cover Configuration Options That Enhance Natural Regulation of Herbivorous Arthropod Abundance in Maize-Fields

Assessment of farming systems and cover configuration options that enhance natural regulation of herbivorous arthropod abundance in maize-fields by Nickson E. Otieno Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Conservation Ecology) at Stellenbosch University Conservation Ecology and Entomology, Faculty of AgriSciences Supervisor: Dr. Shayne M. Jacobs Co-supervisor: Dr. James S. Pryke December 2018 i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: December 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Dissertation format This dissertation is presented as a compilation of 6 chapters. Each chapter is introduced separately and is written, including reference citing and list of bibliography, according to the style of the journal Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. The following chapters have already been submitted for publication in journals Chapter 3: Otieno NE, Pryke, JS, Jacobs, SM. The top-down suppression of arthropod herbivory in inter-cropped maize and organic farms: evidence from δ13C and δ15N stable isotope analyses. Journal of Agronomy for Sustainable Development. Chapter 4: Otieno NE, Jacobs, SM, Pryke, JS. Influence of farm structural complexity features and farming systems on insectivorous birds’ contribution to arthropod herbivore regulation in maize fields. -

AMERICAN MUSEUM No Iltates PUBLISHED by the AMERICAN MUSEUM of NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST at 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y

AMERICAN MUSEUM No iltates PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10024 Number 2825, pp. 1-46, figs. 1-21 August 9, 1985 Behavioral Notes on the Nest-Parasitic Afrotropical Honeyguides (Aves: Indicatoridae) LESTER L. SHORT1 AND JENNIFER F. M. HORNE2 ABSTRACT New data from field studies ofAfrotropical hon- bonds, assisting female honeyguides to enter well- eyguides, examination of label data from speci- defended nests of their hosts. Some Lesser Hon- mens in most ofthe major collections having hon- eyguide (L minor) males seek out duetting pairs eyguides, and review ofthe literature are bases for of their barbet hosts, monitor them, and defend updating the biology ofAfrotropical honeyguides, them against conspecific male honeyguides. Hon- last treated by Friedmann (1955). Three species eyguides parasitizing barbets monitor barbet ac- (Prodotiscus zambesiae, Indicator meliphilus, and tivities about the barbets' roosting or nesting holes L narokensis) have been elevated from subspecific even in the nonbreeding periods. A nestling hon- status, and two new species (Melignomon eisen- eyguide (L minor) was seen making its initial de- trauti, and Indicatorpumilio) have been described parture from its host's (Stactolaema anchietae) since 1955. Emphasizing habitat, foraging habits, nest; a host barbet arriving to feed it shifted rec- foods, interspecific behavior, acoustic and visual ognition from that of a (foster) nestling to that of displays, hosts, and territoriality and breeding a "honeyguide," and immediately and violently habits, new insights are provided into honeyguide attacked the young honeyguide, which was driven biology, although much remains to be accom- out of the barbets' territory. -

Molecular Support for a Sister Group Relationship Between Pici and Galbulae (Piciformes Sensu Wetmore 1960)

JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY 34: 185–197, 2003 Molecular support for a sister group relationship between Pici and Galbulae (Piciformes sensu Wetmore 1960) Ulf S. Johansson and Per G. P. Ericson Johansson, U. S. and Ericson, P. G. P. 2003. Molecular support for a sister group relationship between Pici and Galbulae (Piciformes sensu Wetmore 1960). – J. Avian Biol. 34: 185–197. Woodpeckers, honeyguides, barbets, and toucans form a well-supported clade with approximately 355 species. This clade, commonly referred to as Pici, share with the South American clade Galbulae (puffbirds and jacamars) a zygodactyls foot with a unique arrangement of the deep flexor tendons (Gadow’s Type VI). Based on these characters, Pici and Galbulae are often considered sister taxa, and have in traditional classification been placed in the order Piciformes. There are, however, a wealth of other morphological characters that contradicts this association, and indicates that Pici is closer related to the Passeriformes (passerines) than to Galbulae. Galbulae, in turn, is considered more closely related to the rollers and ground-rollers (Coracii). In this study, we evaluate these two hypotheses by using DNA sequence data from exons of the nuclear RAG-1 and c-myc genes, and an intron of the nuclear myoglobin gene, totally including 3400 basepairs of aligned sequences. The results indicate a sister group relationship between Pici and Galbulae, i.e. monophyly of the Piciformes, and this association has high statistical support in terms of bootstrap values and posterior probabilities. This study also supports several associations within the traditional order Coraciiformes, including a sister group relationship between the kingfishers (Alcedinidae) and a clade with todies (Todidae) and motmots (Momotidae), and with the bee-eaters (Meropidae) placed basal relative to these three groups.