A CHRISTIAN RESPONSE to DUNGEONS and DRAGONS Other Books by Peter Leithart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automatic Writing and the Book of Mormon: an Update

ARTICLES AND ESSAYS AUTOMATIC WRITING AND THE BOOK OF MORMON: AN UPDATE Brian C. Hales At a Church conference in 1831, Hyrum Smith invited his brother to explain how the Book of Mormon originated. Joseph declined, saying: “It was not intended to tell the world all the particulars of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon.”1 His pat answer—which he repeated on several occasions—was simply that it came “by the gift and power of God.”2 Attributing the Book of Mormon’s origin to supernatural forces has worked well for Joseph Smith’s believers, then as well as now, but not so well for critics who seem certain natural abilities were responsible. For over 180 years, several secular theories have been advanced as explanations.3 The more popular hypotheses include plagiarism (of the Solomon Spaulding manuscript),4 collaboration (with Oliver Cowdery, Sidney Rigdon, etc.),5 1. Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., Far West Record: Minutes of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1844 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 23. 2. “Journal, 1835–1836,” in Journals, Volume. 1: 1832–1839, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, vol. 1 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2008), 89; “History of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons 5, Mar. 1, 1842, 707. 3. See Brian C. Hales, “Naturalistic Explanations of the Origin of the Book of Mormon: A Longitudinal Study,” BYU Studies 58, no. -

Espíritos Entre Nós (James Van Praagh)

James Van Praagh Espíritos Entre Nós 2009 Sextante SUMÁRIO INTRODUÇÃO 7 Um Infância cheia de espíritos 11 Dois Deixando o corpo 20 Três Curso básico sobre espíritos 37 Quatro Mortos e vivos49 Cinco O mundo dos espíritos 61 Seis Tudo é energia 82 Sete Como os espíritos se comunicam 105 Oito Alguns viram assombração 121 Nove Para fazer contato 139 Dez Proteção 162 Onze Uma vida iluminada 182 AGRADECIMENTOS SOBRE O AUTOR INTRODUÇÃO Você está lendo este livro porque tem muita curiosidade sobre os espíritos, a comunicação com eles ou a vida após a morte. O interesse por esses assuntos é enorme nos dias de hoje. Um número cada vez maior de pessoas deseja ter conhecimentos aprofundados sobre o tema. Acredito que a sociedade evoluiu espiritualmente, a ponto de abandonar noções pré-concebidas e de abrir a mente para entender a verdade sobre o mundo que chama de espiritual. Quando o meu primeiro livro, Conversando com os espíritos, chegou ao topo da lista dos mais vendidos do jornal New York Times, em 1997, foi considerado um verdadeiro fenômeno editorial. Sua modesta tiragem de 6 mil exemplares subiu rapidamente para 600 mil nos dois meses seguintes. Atribuo o início desse sucesso à minha participação no programa de entrevistas Larry King Live, do canal CNN, no dia 13 de dezembro de 1997. Foi a primeira vez que um médium apareceu como convidado no programa de Larry e que mensagens vindas dos mortos foram transmitidas para uma audiência internacional. As linhas telefônicas ficaram congestionadas enquanto eu estava no ar, e as pessoas continuaram ligando dias depois da transmissão do programa. -

The Spirits of Ouija: Four Decades of Communication by Patrick Keller

December 28, 2013 The Spirits of Ouija: Four Decades of Communication By Patrick Keller From our 2nd Annual Thanksgiving Ouija Session. There are a few great people out there who have served as inspiration for my recent interest in spirit communication through the Ouija, and I’ve blogged about these folks before. If you happen to be looking for books on the topic, you probably won’t find many. I should rephrase that last statement. If you’re looking for serious books by people with experience and years of research, and not written out of fear, you’ll only find a few. Karen A. Dahlman’s latest book, The Spirits of Ouija: Four Dacades of Communication is one of them. I loved the book! Here is my review. Karen A. Dahlman, who is a true Ouija-ologist, begins by giving the reader a brief history of the Ouija Board and the misconceptions that many have, thanks to Hollywood for the most part. As I mentioned in a recent post, Karen and I tend to share the same opinion when it comes to fear and the Ouija. In chapter 2 of her book, Karen says: “Fear is a big reason for Ouija being cast off into an oblivion of negativity. People often fear what they don’t understand. It is easier to fear something than to take the time to learn about it. Fear is first and foremost created by assumptions. Assuming that all communications with the Beyond, coming from outside our typical experiences and the world of our everyday senses and faculties, is critically labeled ridiculous or blasphemous, is narrow-minded in itself. -

A Glimpse at Spiritualism

A GLIMPSE AT SPIRITUALISM P.V JOITX J. BIRCH ^'*IiE term Spiritualism, as used by philosophical writers denotes the opposite of materialism., but it is also used in a narrower sense to describe the belief that the spiritual world manifests itself by producing in the physical world, effects inexplicable by the known laws of natural science. Many individuals are of the opinion that it is a new doctrine: but in reality the belief in occasional manifesta- tions of a supernatural world has probably existed in the human mind from the most primitive times to the very moment. It has filtered down through the ages under various names. As Haynes states in his book. Spirifttallsiii I'S. Christianity, 'Tt has existed for ages in the midst of heathen darkness, and its presence in savage lands has been marked by no march of progress, bv no advance in civilization, by no development of education, by no illumination of the mental faculties, by no increase of intelligence, but its acceptance has been productive of and coexistent with the most profound ignor- ance, the most barbarous superstitions, the most unspeakable immor- talities, the basest idolatries and the worst atrocities which the world has ever known."' In Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Greece and Rome such things as astrology, soothsaying, magic, divination, witchcraft and necromancy were common. ]\ loses gives very early in the history of the human race a catalogue of spirit manifestations when he said: "There shall not be found among you any one that maketh his son or his daugh- ter to pass through the fire, or that useth divination, or an observer of times, or an enchanter, or a witch, or a charmer, or a consulter with familiar spirits, or a wizard, or a necromancer. -

Pentecostalism and Shamanism in Asia and Beyond: an Inter-Disciplinary Analysis

Pentecostalism and Shamanism in Asia and Beyond An Inter-disciplinary Analysis Alena Govorounova “To every action there is always an equal and opposite reaction.” Isaac Newton, Third Law of Motion, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica “The unlike is joined together, and from differences results the most beautiful harmony, and all things take place by strife.” Heraclitus of Ephesus, On Nature Erich Neumann suggests in The Origins and History of Con- sciousness that human consciousness is subjected to the constant process of centroversion and differentiation (Neumann 1973, 261). This tendency of human thought—to constantly strive toward polarities and reorganize itself again as a holistic mode—seems to pertain to all layers of human cog- nitive architecture, from archetypal pre-reflective self-awareness to highly analytical interpretative supra-consciousness. It is reflected in the evolution of cultures and civilizations and it seems to be the driving force behind his- * Alena Govorounova is a Research Associate at the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. The quotations from the Bible are from the niv (New International Version, Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1984). 54 alena govorounova | 55 torical changes in the intellectual climate and scientific paradigm shifts (see Kuhn 1962). As Friedrich Nietzsche (1999 [1888]; 1966 [1886]) once ironi- cally observed, we are doomed to think in opposites and controversies, we are trapped in categorical dualisms of “good and evil,” we are conditioned by contrast-based human language, where each unit of meaning is defined against what it is not. We are carried away in the endless play of différance1 in search for identity and meaning and we need the Other to define who we are. -

Road to Spiritism

THE ROAD TO SPIRITISM By MARIA ENEDINA LIMA BEZERRA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2002 Copyright 2002 By Maria Enedina Lima Bezerra To my beloved parents, Abelardo and Edinir Bezerra, for all the emotional and spiritual support that they gave me throughout this journey; and to the memory of my most adored grandmother, Maria do Carmo Lima, who helped me sow the seeds of the dream that brought me here. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My first expressions of gratitude go to my parents for always having believed in me and supported my endeavors and for having instilled in me their heart-felt love for learning and for peoples and lands beyond our own. Without them, I would not have grown to be such a curious individual, always interested in leaving my familiar surroundings and learning about other cultures. My deepest gratitude goes to the Spiritists who so warmly and openly welcomed me in their centers and so generously dedicated their time so that 1 could conduct my research. With them I learned about Spiritism and also learned to accept and respect a faith different from my own. It would be impossible for me to list here the names of all the Spiritists I interviewed and interacted with. In particular, I would like to thank the people of Grupo Espirita Paulo e Estevao, Centra Espirita Pedro, o Apostolo de Jesus, and Centro Espirita Grao de Mostarda. Without them, this study would not have been possible. -

Mediumship and the Economy of Luck and Fate: Contemporary Chinese Belief Trends Behind the Filmic Folklore

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/FEJF2016.65.bao MEDIUMSHIP AND THE ECONOMY OF LUCK AND FATE: CONTEMPORARY CHINESE BELIEF TRENDS BEHIND THE FILMIC FOLKLORE Huai Bao Abstract: This study explores the pen spirit, a mediumistic game simplified out of fuji, which is shown in a number of popular horror films in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). While Chinese literary works in the past often made reference to fuji as an ancient Chinese mediumistic ritual, the communist government has suppressed expressions on the supernatural in publications and official media, but not in films – at least not in the popular pen spirit series. What is a pen spirit? Why is it so popular in China, especially among Chinese youngsters? Is there a ‘cultural obsession’ among the Chinese with fate, luck, and divination? This study seeks to discover the evolution of the pen spirit and the socio-cultural psychological dimensions behind the phenomenon. Keywords: divination, economy of luck and fate, filmic folklore, fuji, medium- ship, supernatural INTRODUCTION In the past few years, a number of low-budget pen spirit thrillers have been released in the PRC with great box office outcome. These films may be classified as filmic folklore, a term coined by Juwen Zhang, which is defined as “a folklore or folklore-like performance that is represented, created, or hybridized in fictional film” (2005: 267). These films have been released and publicized by the media in the PRC largely due to their filmic folkloric nature. A 2014 news report on the lawsuit between some Beijing-based film production companies brought attention to the popularity of horror films featuring the pen spirit – a popular form of mediumship in China similar to the Ouija board in the West (more on Ouija board see Brunvand 1998 [1996]: 534). -

The Occult History, Beliefs and Practices

The Occult An Evaluation from the Theological Perspective of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod April 2005 (updated May 2014) History, Beliefs and Practices Identity: The term “occult” derives from a Latin word that means “hidden” or “secret.” In a general sense, “the Occult” refers to real or imagined “supernatural” happenings that go beyond the realm of the human senses [“paranormal”]. More specifically, “Occult” can denote magical practices, very often secret, and the individuals who perform them. Occultic phenomena assume the presence and assistance of supernatural or spiritual forces or beings. The practices and practitioners of the Occult are highly diverse and are present in many organizations and movements (e.g., Satanism, New Age, Wicca [neopaganism]). Founders: Occultic practices and phenomena—both ancient and modern—have no single origin or founder. In the contemporary situation, certain individuals and groups receive public attention through the promotion of their literature and in some cases through media exposure. History: The Encyclopedia Britannica begins its comprehensive article on “occultism” by stating that occultic “beliefs and practices—principally magical and divinatory—have occurred in all human societies throughout recorded history….”1 Common to all human societies, it further notes, are divination, magic, witchcraft, alchemy,2 and astrology. The Bible singles out and condemns occultic practices such as child sacrifice, divination or sorcery, the use of mediums, casting of spells, spiritism and necromancy present in ancient Canaanite cultures (Deut. 18:9-13).3 In the late 20th century and at the beginning of the 21st century, occultic beliefs and practices have become increasingly common, present for instance in the so-called “Neo-Pagan” movement, in which participants seek to use rites, chants, and charms, etc., to predict the future, improve the human condition and ward off evils (see evaluation on Wicca). -

Spirit Possession Perspectives on Pastoral Assessment and Care

Theology ︱ Dr Marta Illueca Spirit possession Perspectives on pastoral assessment and care Most of us are familiar with hroughout the past two decades, symptoms that are characteristic of both demonic possession as depicted and despite widespread demonic possession, and mental health in popular culture, for example in T scepticism, there has been an disorders. Practitioners often fail to horror films such as The Exorcist. increase in interest from the academic discern what a patient needs, i.e., medical While these representations community on the phenomenon of attention and psychiatric diagnosis, or are usually exaggerated, they spiritual distress related to spirit or spiritual intervention. The consequences are frequently based on real-life demonic possession. In her graduate of misdiagnosis can compromise well- accounts of the phenomenon. work at Yale Divinity School, Dr Marta being, and lead to social stigma. Evolution of the knowledge about demonic possession. Despite widespread academic Illueca researches the topic of demonic Graphic design by Cynde A. Bimbi, CAB Graphics & Design, USA. scepticism, pastoral care and possession: spirit possession by an evil Dr Illueca notes that formal research mental health practitioners are entity. Her background in both medicine and empirical data are sparse, which possession, and how it differs from or microbial contamination. In the worst of demonic possession is described becoming increasingly aware and theology makes her ideally placed has led to a misrepresentation of those the mental health disorders with which cases the evil spirit controls and uses worldwide across cultures and continents. of the affliction, and the need to inform and advise on this topic. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

I See Dead People: a Look at After-Death Communication

CHRISTIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE P.O. Box 8500, Charlotte, NC 28271 Feature Article: DD810 I SEE DEAD PEOPLE: A LOOK AT AFTER-DEATH COMMUNICATION by Marcia Montenegro This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 25, number 1 (2002). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal go to: http://www.equip.org SYNOPSIS Recent years have witnessed a revival of interest in contact with the dead. Much of this interest is due to the popularity of mediums such as John Edward, Sylvia Browne, and James Van Praagh. Edward and Van Praagh both have popular television shows, and all three have written best-selling books and have appeared on numerous talk shows. Several movies, such as the hit, The Sixth Sense, have also made spirit contact the theme of their stories. Sylvia Browne and James Van Praagh do not practice spirit contact in a vacuum; they have complex spiritual beliefs spelled out in their books and expressed on talk shows. While Edward claims to be Roman Catholic, Browne and Van Praagh have openly rejected orthodox Christianity and embraced a nonjudgmental God more tailored to New Age beliefs. Edward, Browne, and Van Praagh all have backgrounds that include heavy psychic experiences as well as research into the occult and psychic worlds. Skeptics have denounced these mediums and attempted to expose them as frauds. This raises questions: Are all mediums frauds, and can we be sure that they are? Is it possible that some mediums may be receiving information from a demonic source? Is the classification of mediums as frauds a helpful response? Despite seemingly being debunked by skeptics, mediums still generate strong interest. -

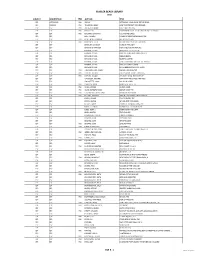

Flagler Beach Library Esp P. 1

FLAGLER BEACH LIBRARY 2015 SUBJECT DESCRIPTION TYPE AUTHOR TITLE ESP ASTROLOGY PBK ZODIAC ASTROLOGY: YOUR GUIDE TO THE STARS ESP DREAMS PBK THURSTON, MARK HOW TO INTERPRET YOUR DREAMS ESP ESP PBK ALTEA, ROSEMARY EAGLE AND THE ROSE ESP ESP PBK BADER, LOIS COMPANION GUIDE TO THE ONLY PLANET OF CHOICE ESP ESP PBK BALDWIN, CHRISTINA CALLING THE CIRCLE ESP ESP BALL, PAMELA POWER OF CREATIVE THINKING. THE ESP ESP PBK BOYER & NISSENBAUM SALEM POSSESSED ESP ESP PBK BRADY & ST. LIFER DISCOVERING YOUR SOUL MISSION ESP ESP BRINKLEY, DANNION SAVED BY THE LIGHT ESP ESP BROWNE & HARRISON PAST LIVES, FUTURE HEALING ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA ADVENTURES OF A PSYCHIC ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA GOD, CREATION AND TOOLS FOR LIFE ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA PHENOMENON ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SECRET SOCIETIES ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SECRETS AND MYSTERIES OF THE WORLD ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SPIRITUAL CONNECTIONS ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SYLVIA BROWN'S BOOK OF ANGEL ESP ESP PBK CALLEMAN, CARL JOHAN MAYAN CALENDAR, THE ESP ESP PBK CAPUTO, THERESA THERE'S MORE TO LIFE THAN THIS ESP ESP PBK CAPUTO, THERESA YOU CAN'T MAKE THIS STUFF UP ESP ESP CAVENDISH, RICHARD MAN MYTH AND MAGIC PART TWO ESP ESP CHOQUETTE, SONIA ASK YOUR GUIDES ESP ESP PBK CIANCIOSI, JOHN MEDITATIVE PATH, THE ESP ESP PBK CLARK, JEROME UNEXPLAINED ESP ESP PBK CLOW, BARBARA HAND MAYAN CODE, THE ESP ESP PBK COOPER, MILTON WILLIAM BEHOLD A PALE HORSE ESP ESP PBK DELONG, DOUGLAS ANCIENT TEACHINGS FOR BEGINNERS ESP ESP DIXON, JEANNE CALL TO GLORY, THE ESP ESP DIXON, JEANNE MY LIFE AND PROPHECIES ESP ESP DOSSEY, LARRY POWER OF PREMONITIONS, THE ESP ESP DRUSE, ELEANOR JOURNALS OF ELEANOR DRUSE ESP ESP EADIE, BETTY J.