A Revolutionary Meeting of Minds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francois Jacob Memorial

RETROSPECTIVE RETROSPECTIVE Francois Jacob memorial Arthur B. Pardee1 Department of Adult Oncology, Dana-Farber Institute, Boston, MA 02115 Dr. Francois Jacob is one of a handful of the DNA would integrate into the bacterial chro- 20th century’smostdistinguishedlifescien- mosome and remain dormant or, at other tists. His research with Dr. Jacques Monod, times, would kill the cell. like that of Watson and Crick, provided the Jacob’s next major contribution, in collab- foundations for understanding mechanisms oration with Dr. Jacques Monod, was to in- of genetic regulation of life processes such vestigate how a gene is regulated. Remark- as cell differentiation and defects in diseases. ably, native E. coli synthesize β-galactosidase Jacob joined the College de France in 1964 only when lactose is available. Some mutated and shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology bacteria can make the enzyme in the absence or Medicine 1965 with Jacques Monod of inducer. Monod’s initial idea was that and Andre Lwoff. He was elected to the these constitutive bacteria activate the gene National Academy of Sciences (NAS) USA by synthesizing an intracellular lactose-like in 1969. inducer molecule. Jacob was born in 1920 in a French Jewish To investigate this model, interrupted family; his grandfather was a four-star gen- mating was applied to bring the β-galactosi- eral. He began to study medicine before dase gene of a donor bacterium into a consti- World War II, in which he served as a mil- tutive receptor. According to the induction itary officer in the Free French Army and was model, the mated cell should produce en- badly wounded in an air raid. -

Freedom Quotes, May 2015 May 1. Freedom Is Not Worth Having If It

Freedom Quotes, May 2015 May 1. Freedom is not worth having if it does not include the freedom to make mistakes. Mahatma Ganhdi May 2. When a man is denied the right to live the life he believes in, he has no choice but to become an outlaw. Nelson Mandela May 3. The most important kind of freedom is to be what you really are. You trade in your reality for a role. There can’t be any large-scale revolution until there’s a personal revolution, on an individual level. It’s got to happen inside first. Jim Morrison May 4. Freedom lies in being bold. Robert Frost May 5. People demand freedom of speech as a compensation for the freedom of thought they seldom use. Soren Kierkegaard May 6. Those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves. Abraham Lincoln May 7. I am free, no matter what rules surround me. If I find them tolerable, I tolerate them; if I find them too obnoxious, I break them. I am free because I know that I alone am morally responsible for everything I do. Robert A. Heinlein May 8. If we don’t believe in freedom of expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all. Noam Chomsky May 9. Freedom is nothing else but a chance to be better. Albert Camus May 10. ---To be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others. Nelson Mandela May 11. -

Quiet Debut'' of the Double Helix: a Bibliometric and Methodological

Journal of the History of Biology Ó Springer 2009 DOI 10.1007/s10739-009-9183-2 Revisiting the ‘‘Quiet Debut’’ of the Double Helix: A Bibliometric and Methodological note on the ‘‘Impact’’ of Scientific Publications YVES GINGRAS De´partement d’histoire Universite´ du Que´bec a` Montre´al C.P. 8888, Suc. Centre-Ville Montreal, QC H3C-3P8 Canada E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The object of this paper is two-fold: first, to show that contrary to what seem to have become a widely accepted view among historians of biology, the famous 1953 first Nature paper of Watson and Crick on the structure of DNA was widely cited – as compared to the average paper of the time – on a continuous basis from the very year of its publication and over the period 1953–1970 and that the citations came from a wide array of scientific journals. A systematic analysis of the bibliometric data thus shows that Watson’s and Crick’s paper did in fact have immediate and long term impact if we define ‘‘impact’’ in terms of comparative citations with other papers of the time. In this precise sense it did not fall into ‘‘relative oblivion’’ in the scientific community. The second aim of this paper is to show, using the case of the reception of the Watson–Crick and Jacob–Monod papers as concrete examples, how large scale bibliometric data can be used in a sophisticated manner to provide information about the dynamic of the scientific field as a whole instead of limiting the analysis to a few major actors and generalizing the result to the whole community without further ado. -

Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler a Dissertati

Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Chair Ann Anagnost Stevan Harrell Danny Hoffman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology ©Copyright 2018 Darren T. Byler University of Washington Abstract Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Department of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies This study argues that Uyghurs, a Turkic-Muslim group in contemporary Northwest China, and the city of Ürümchi have become the object of what the study names “terror capitalism.” This argument is supported by evidence of both the way state-directed economic investment and security infrastructures (pass-book systems, webs of technological surveillance, urban cleansing processes and mass internment camps) have shaped self-representation among Uyghur migrants and Han settlers in the city. It analyzes these human engineering and urban planning projects and the way their effects are contested in new media, film, television, photography and literature. It finds that this form of capitalist production utilizes the discourse of terror to justify state investment in a wide array of policing and social engineering systems that employs millions of state security workers. The project also presents a theoretical model for understanding how Uyghurs use cultural production to both build and refuse the development of this new economic formation and accompanying forms of gendered, ethno-racial violence. -

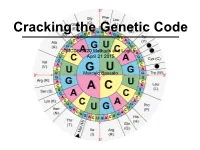

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

The Eighth Day of Creation”: Looking Back Across 40 Years to the Birth of Molecular Biology and the Roots of Modern Cell Biology

“The Eighth Day of Creation”: looking back across 40 years to the birth of molecular biology and the roots of modern cell biology Mark Peifer1 1 Department of Biology and Curriculum in Genetics and Molecular Biology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB#3280, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3280, USA * To whom correspondence should be addressed Email: [email protected] Phone: (919) 962-2272 1 Forty years ago, Horace Judson’s “The Eight Day of Creation” was published, a book vividly recounting the foundations of modern biology, the molecular biology revolution. This book inspired many in my generation. The anniversary provides a chance for a new generation to take a look back, to see how science has changed and hasn’t changed. Many central players in the book, including Sydney Brenner, Seymour Benzer and Francois Jacob, would go on to be among the founders of modern cell, developmental, and neurobiology. These players come alive via their own words, as complex individuals, both heroes and anti-heroes. The technologies and experimental approaches they pioneered, ranging from cell fractionation to immunoprecipitation to structural biology, and the multidisciplinary approaches they took continue to power and inspire our work today. In the process, Judson brings out of the shadows the central roles played by women in many of the era’s discoveries. He provides us with a vision of how science and scientists have changed, of how many things about our endeavor never change, and how some new ideas are perhaps not as new as we’d like to think. 2 In 1979 Horace Judson completed a ten-year project about cell and molecular biology’s foundations, unveiling “The Eighth Day of Creation”, a book I view as one of the most masterful evocations of a scientific revolution (Judson, 1979). -

In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick Discovered the Structure of DNA in the Now-Famous Scientific Narrative Known As the “Race Towards the Double Helix”

THE NARRATIVES OF SCIENCE: LITERARY THEORY AND DISCOVERY IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY PRIYA VENKATESAN In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA in the now-famous scientific narrative known as the “race towards the double helix”. Meanwhile in France, Roland Barthes published his first book, Writing Degree Zero, on literary theory, which became the intellectual precursor for the new human sciences that were developing based on Saussurean linguistics. The discovery by Watson and Crick of the double helix marked a definitive turning point in the development of the life sciences, paving the way for the articulation of the genetic code and the emergence of molecular biology. The publication by Barthes was no less significant, since it served as an exemplar for elucidating how literary narratives are structured and for formulating how textual material is constructed. As Françoise Dosse notes, Writing Degree Zero “received unanimous acclaim and quickly became a symptom of new literary demands, a break with tradition”.1 Both the work of Roland Barthes and Watson and Crick served as paradigms in their respective fields. Semiotics, the field of textual analysis as developed by Barthes in Writing Degree Zero, offered a new direction in the structuring of narrative whereby each distinct unit in a story formed a “code” or “isotopy” that categorizes the formal elements of the story. The historical concurrence of the discovery of the double helix and the publication of Writing Degree Zero may be mere coincidence, but this essay is an exploration of the intellectual influence that both events may have had on each other, since both the discovery of the double helix and Barthes’ publication gave expression to the new forms of knowledge 1 Françoise Dosse, History of Structuralism: The Rising Sign, 1945-1966, trans. -

Albert Camus and Absurd Communication: from Undecidability to Übercommunication

Albert Camus and Absurd Communication: From Undecidability to Übercommunication by Jorge Lizarzaburu B.A., USFQ, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication 2012 This thesis entitled: Albert Camus and Absurd Communication: From Undecidability to Übercommunication written by Jorge M. Lizarzaburu has been approved for the Department of Communication Gerard Hauser Janice Peck Robert Craig Date 5/31/2012 The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline iii Lizarzaburu, Jorge M. (M.A., Communication, Department of Communication) Albert Camus and Absurd Communication: From Undecidability to Übercommunication Thesis directed by professor Gerard Hauser Communication conceived as understanding is a normative telos among scholars in the field. Absurdity, in the work of Albert Camus, can provide us with a framework to go beyond communication understood as a binary (understanding and misunderstanding) and propose a new conception of communication as absurd. That is, it is an impossible task, however necessary thus we need to embrace its absurdity and value the effort itself as much as the result. Before getting into Camus’ arguments I explain the work of Friedrich Nietzsche to understand the French philosopher in more detail. I describe eternal recurrence and Übermensch as two concepts that can be related to communication as absurd. Then I explain Camus’ notion of absurdity using a Nietzschean lens. -

Cover June 2011

z NOBEL LAUREATES IN Qui DNA RESEARCH n u SANGRAM KESHARI LENKA & CHINMOYEE MAHARANA F 1. Who got the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1933) for discovering the famous concept that says chromosomes carry genes? a. Gregor Johann Mendel b. Thomas Hunt Morgan c. Aristotle d. Charles Darwin 5. Name the Nobel laureate (1959) for his discovery of the mechanisms in the biological 2. The concept of Mutations synthesis of ribonucleic acid and are changes in genetic deoxyribonucleic acid? information” awarded him a. Arthur Kornberg b. Har Gobind Khorana the Nobel Prize in 1946: c. Roger D. Kornberg d. James D. Watson a. Hermann Muller b. M.F. Perutz c. James D. Watson 6. Discovery of the DNA double helix fetched them d. Har Gobind Khorana the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1962). a. Francis Crick, James Watson, Rosalind Elsie Franklin b. Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Willkins c. James Watson, Maurice Willkins, Rosalind Elsie Franklin 3. Identify the discoverer and d. Maurice Willkins, Rosalind Elsie Franklin and Francis Crick Nobel laureate of 1958 who found DNA in bacteria and viruses. a. Louis Pasteur b. Alexander Fleming c. Joshua Lederberg d. Roger D. Kornberg 4. A direct link between genes and enzymatic reactions, known as the famous “one gene, one enzyme” hypothesis, was put forth by these 7. They developed the theory of genetic regulatory scientists who shared the Nobel Prize in mechanisms, showing how, on a molecular level, Physiology or Medicine, 1958. certain genes are activated and suppressed. Name a. George Wells Beadle and Edward Lawrie Tatum these famous Nobel laureates of 1965. -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr. -

Albert Camus' Dialogue with Nietzsche and Dostoevsky Sean Derek Illing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Between nihilism and transcendence : Albert Camus' dialogue with Nietzsche and Dostoevsky Sean Derek Illing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Illing, Sean Derek, "Between nihilism and transcendence : Albert Camus' dialogue with Nietzsche and Dostoevsky" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1393. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1393 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BETWEEN NIHILISM AND TRANSCENDENCE: ALBERT CAMUS’ DIALOGUE WITH NIETZSCHE AND DOSTOEVSKY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Sean D. Illing B.A., Louisiana State University, 2007 M.A., University of West Florida, 2009 May 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the product of many supportive individuals. I am especially grateful for Dr. Cecil Eubank’s guidance. As a teacher, one can do no better than Professor Eubanks. Although his Socratic glare can be terrifying, there is always love and wisdom in his instruction. It is no exaggeration to say that this work would not exist without his support. At every step, he helped me along as I struggled to articulate my thoughts. -

Albert Camus As Moral Politician

Articles The Passion and the Spirit: Albert Camus as Moral Politician Jan Klabbers* TABLE OF CONTENTS: I. Introduction. – II. A manifesto. – III. On Camus. – IV. Camus and the virtues. – V. A smouldering continent. – V.1. Financial crisis. – V.2. Refugee flows. – V.3. Russia and Crimea. – V.4. Refer- enda, governance, responsibility. – VI. To conclude. ABSTRACT: This essays addresses the curious circumstance that for all their visibility on blogs, twitter and the 'op-ed' pages of newspapers, public intellectuals offer remarkably little ethical guidance regarding current events and crises. These intellectuals may offer their expertise (explanations, predictions), but do not provide much ethical inspiration, almost as if 'right' and 'wrong' have be- come meaningless categories. Things were different a few generations ago, when the likes of Al- bert Camus would search their souls in order to figure out how to live. This essay portrays Camus as private citizen and public moralist, and briefly discusses current political events in a mindset inspired by Camus. KEYWORDS: Albert Camus – virtue ethics – political crisis – Europe – public intellectuals. “… for us Europe is a home of the spirit where for the last twenty centuries the most amazing adventure of the human spirit has been going on”.1 I. Introduction Europe is, if not on fire, at least smouldering. The last couple of years alone have seen the continent confronted with the unabashed annexation of the Crimea; the shooting down, accidental or otherwise, of civilian aircraft; a financial crisis and a country on the brink of bankruptcy; and an influx of refugees seen as threatening in its own right, and which threatens to bring down the European Union (EU) and threatens to turn Europe * Academy Professor (Martti Ahtisaari Chair), University of Helsinki, and Visiting Research Professor, Erasmus Law School, Erasmus University Rotterdam, [email protected].