The Meeting of Two Cultures Public Television on the Threshold of the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prohibition Premieres October 2, 3 & 4

Pl a nnerMichiana’s bi-monthly Guide to WNIT Public Television Issue No. 5 September — October 2011 A FILM BY KEN BURNS AND LYNN NOVICK PROHIBITION PREMIERES OCTOBER 2, 3 & 4 BrainGames continues September 29 and October 20 Board of Directors Mary’s Message Mary Pruess Chairman President and GM, WNIT Public Television Glenn E. Killoren Vice Chairmen David M. Findlay Rodney F. Ganey President Mary Pruess Treasurer Craig D. Sullivan Secretary Ida Reynolds Watson Directors Roger Benko Janet M. Botz WNIT Public Television is at the heart of the Michiana community. We work hard every Kathryn Demarais day to stay connected with the people of our area. One way we do this is to actively engage in Robert G. Douglass Irene E. Eskridge partnerships with businesses, clubs and organizations throughout our region. These groups, David D. Gibson in addition to the hundreds of Michiana businesses that help underwrite our programs, William A. Gitlin provide WNIT with constant and immediate contact to our viewers and to the general Tracy D. Graham Michiana community. Kreg Gruber Larry D. Harding WNIT maintains strong partnerships and active working relationship with, among others, James W. Hillman groups representing the performing arts – Arts Everywhere, Art Beat, the Fischoff National Najeeb A. Khan Chamber Music Association, the Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival, the Krasl Art Center in Evelyn Kirkwood Kevin J. Morrison St. Joseph, the Lubeznik Center for the Arts in Michigan City and the Southwest Michigan John T. Phair Symphony; civic and cultural organizations like the Center for History, Fernwood Botanical Richard J. Rice Garden and Nature Center and the Historic Preservation Commission; educational, social Jill Richardson and healthcare organizations such as WVPE National Public Radio, the St. -

Tzp Group Sells This Old House Ventures, Llc to Roku, Inc

New York, NY – March 19, 2021 TZP GROUP SELLS THIS OLD HOUSE VENTURES, LLC TO ROKU, INC. TZP Group LLC (“TZP”) today announced the realization of its investment in This Old House Ventures, LLC (“This Old House”), the leading multi-platform home enthusiast brand, with a sale to Roku, Inc. (NASDAQ: ROKU). Financial terms of the sale were not disclosed. This Old House invented the home improvement television genre in 1979, and now reaches more than 20 million house-proud consumers each month with trusted information and expert advice through its Emmy® award-winning television shows, digital properties, and magazine. This Old House and Ask This Old House remain the two highest-rated home improvement shows on television, and have earned 19 Emmy® Awards and 102 nominations. The company provides brand-safe content for a roster of top advertisers across TV, web, OTT, social, podcast and print platforms. “TZP is proud to have been the steward of this wonderful brand over the last five years. It’s been a joy to work with Dan Suratt, Eric Thorkilsen and the rest of the outstanding This Old House management team to transform the business into a true, multi-media powerhouse that reaches consumers everywhere,” said Bill Hunscher, Partner at TZP. “We want to thank the team, the talent and the rest of the supporting cast for their excellent work and unwavering commitment in moving the brand forward.” “TZP provided great support in helping us make such a storied brand even more powerful and attractive to consumers and partners,” said Dan Suratt, CEO, This Old House. -

PBS and the Young Adult Viewer Tamara Cherisse John [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-12-2012 PBS and the Young Adult Viewer Tamara Cherisse John [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation John, Tamara Cherisse, "PBS and the Young Adult Viewer" (2012). Research Papers. Paper 218. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/218 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PBS AND THE YOUNG ADULT VIEWER by Tamara John B.A., Radio-Television, Southern Illinois University, 2010 B.A., Spanish, Southern Illinois University, 2010 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree Department of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2012 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL PBS AND THE YOUNG ADULT VIEWER By Tamara John A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Professional Media and Media Management Approved by: Dr. Paul Torre, Chair Dr. Beverly Love Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale March 28, 2012 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF Tamara John, for the Master of Science degree in Professional Media and Media Management, presented on March 28, 2012, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: PBS AND THE YOUNG ADULT VIEWER MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. Paul Torre Attracting and retaining teenage and young adult viewers has been a major challenge for most broadcasters. -

Solon Springs Channel Lineup Choose the Package That fits Your Life

Solon Springs Channel Lineup Choose the package that fits your life. B C P U Basic Choice Plus Ultimate 10 + Local Channels 60 + Channels 130 + Channels 160 + Channels including Locals including Locals including Locals Basic 2 | 2.1 Minnesota Channel 6 | 6.1 C-SPAN 10 | 10.1 WDIO - ABC HD 3 | 3.1 QVC 7 | 7.1 PBS HD 11 | 11.1 KQDS - FOX HD 4 | 4.1 The Weather Channel 8 | 8.1 WDIO - MeTV 12 | 12.1 KBJR - NBC HD 5 | 5.1 KBJR - CBS HD 9 | 9.1 KBJR - MyNetwork Choice 14 | 14.1 RFD 29 | 29.1 TLC 45 | 45.1 Comedy TV 61 | 61.1 Big Ten Network 15 | 15.1 TBS 30 | 30.1 FX 46 | 46.1 AMC 62 | 62.1 MSNBC 16 | 16.1 Lifetime 32 | 32.1 Fox Sports 1 47 | 47.1 E! 63 | 63.1 Evine 17 | 17.1 National Geographic 33 | 33.1 Fox Sports Wisconsin 48 | 48.1 NBC Sports Network 64 | 64.1 C-SPAN 2 18 | 18.1 Freeform 34 | 34.1 ESPN 2 49 | 49.1 Outdoor Channel 65 | 65.1 INSP 19 | 19.1 Cartoon Network 35 | 35.1 ESPN 50 | 50.1 Sportsman Channel 66 | 66.1 EWTN 20 | 20.1 SyFy 36 | 36.1 HLN 51 | 51.1 Hallmark Channel 67 | 67.1 Disney XD 21 | 21.1 TCM 37 | 37.1 Fox News Channel 52 | 52.1 HGTV 68 | 68.1 HSN 22 | 22.1 Disney Channel 38 | 38.1 Tru TV 53 | 53.1 Oxygen 70 | 70.1 Bravo 23 | 23.1 FXX 39 | 39.1 CNN 55 | 55.1 Travel Channel 71 | 71.1 ID 24 | 24.1 USA Network 40 | 40.1 Food Network 56 | 56.1 Discovery Channel 74 | 74.1 POP 25 | 25.1 A&E 41 | 41.1 Revolt 57 | 57.1 Animal Planet 75 | 74.1 OWN 26 | 26.1 TNT 42 | 42.1 Disney Junior 59 | 59.1 History Channel 76 | 76.1 Fox Business Network 27 | 27.1 WGN 44 | 44.1 CNBC 60 | 60.1 WE TV 97 | 97.1 Science Channel 28 | 28.1 Fido -

Minnesota History: Building a Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Minnesota History: Building A Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund January 2011 Table of Contents Letter from the Minnesota Historical Society Director . 1 Overview . 2 Feature Stories on Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund (ACHF) History Grants, Programs, Partnerships and Initiatives Inspiring Students and Teachers . 6 Investing in People and Communities . 10 Dakota and Ojibwe: Preserving a Legacy . .12 Linking Past, Present and Future . .15 Access For Everyone . .18 ACHF History Appropriations Language . .21 Full Report of ACHF History Grants, Programs, Partnerships and Statewide Initiatives Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants (Organized by Legislative District) . 23 Statewide Historic Programs . 75 Statewide History Partnership Projects . 83 “Our Minnesota” Exhibit . .91 Survey of Historical and Archaeological Sites . 92 Minnesota Digital Library . 93 Estimated cost of preparing and printing this report (as required by Minn. Stat. § 3.197): $18,400 Upon request the 2011 report will be made available in alternate format such as Braille, large print or audio tape. For TTY contact Minnesota Relay Service at 800-627-3529 and ask for the Minnesota Historical Society. For more information or for paper copies of the 2011 report contact the Society at: 345 Kellogg Blvd W., St Paul, MN 55102, 651-259-3000. The 2011 report is available at the Society’s website: www.mnhs.org/legacy. COVER IMAGES, CLOCKWIse FROM upper-LEFT: Teacher training field trip to Oliver H. -

Firstchoice Wusf

firstchoice wusf for information, education and entertainment • decemBer 2009 André Rieu Live in Dresden: Wedding at the Opera Recorded at Dresden’s Semper Opera House in 2008, this musical confection from André Rieu is both a concert and a real wedding party in one of the world’s most beautiful opera houses. The charming bride and groom, part of the famous “Vienna Debutantes,” are joined by 40 pairs of dancers from the Elmayer Dance School in Vienna, as well as sopranos Mirusia Louwerse and Carmen Monarcha, the Platinum Tenors, baritone Morschi Franz, and the Johann Strauss Orchestra and Choir. Airs Tuesday, December 1 at 8 p.m. from the wusf gm Season’s As you plan your year-end Greetings charitable giving, please consider a contribution to HE HOLIDAYS CAME EARLY THIS YEAR WUSF. It’s tax-deductible, T at WUSF Public Broadcasting. Thanks to you, WUSF 89.7’s Fall Membership Campaign it’s easy and it will make a was an unqualified success. We welcomed difference in your community. 1,050 new members to our family and raised more than $400,000 from new and renewing Just call Cathy Coccia at members. Bravo to everyone involved! 813-974-8624 or go online Speaking about our loyal supporters, we recently celebrated our Cornerstone Society to wusf.org and click members during the second annual Corner- on the Give Now button. stone Appreciation event. This year’s guest was the witty and insightful Susan Stamberg, Make a gift that gives back – an NPR special correspondent. She touched to you and your neighbors. -

AETN Resource Guide for Child Care Professionals

AAEETTNN RReessoouurrccee GGuuiiddee ffoorr CChhiilldd CCaarree PPrrooffeessssiioonnaallss Broadcast Schedule PARENTING COUNTS RESOURCES A.M. HELP PARENTS 6:00 Between the Lions The resource-rich PARENTING 6:30 Maya & Miguel COUNTS project provides caregivers 7:00 Arthur and parents a variety of multi-level 7:30 Martha Speaks resources. Professional development 8:00 Curious George workshops presented by AETN provide a hands-on 8:30 Sid the Science Kid opportunity to explore and use the videos, lesson plans, 9:00 Super WHY! episode content and parent workshop formats. Once child 9:30 Clifford the Big Red Dog care providers are trained using the materials, they are able to 10:00 Sesame Street conduct effective parent workshops and provide useful 11:00 Dragon Tales handouts to parents and other caregivers. 11:30 WordWorld P.M. PARENTS AND CAREGIVERS 12:00 Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood CAN ASK THE EXPERTS 12:30 Big Comfy Couch The PBS online Expert Q&A gives 1:00 Reading Rainbow parents and caregivers the opportunity to 1:30 Between the Lions ask an expert in the field of early childhood 2:00 Caillou development for advice. The service includes information 2:30 Curious George about the expert, provides related links and gives information 3:00 Martha Speaks about other experts. Recent subjects include preparing 3:30 Wordgirl children for school, Internet safety and links to appropriate 4:00 Fetch with Ruff Ruffman PBS parent guides. The format is easy and friendly. To ask 4:30 Cyberchase the experts, visit http://www.pbs.org/parents/issuesadvice. STAY CURRENT WITH THE FREE STATIONBREAK NEWS FOR EDUCATORS AETN StationBreak News for Educators provides a unique (and free) resource for parents, child care professionals and other educators. -

Wordgirl Lesson Plan

WordGirl Super Storytelling! Lesson Summary Estimated Time: 35-40 minutes What makes a good story? One place to learn is by watching PBS KIDS where stories come to life—like in WordGirl! Engaging characters, unique settings, and crazy problems to overcome are just some of the elements of good storytelling. From battling with brothers to catching criminals, WordGirl brings exciting and interesting stories to her audience. Students will try their hand at storytelling by using WordGirl images as a pattern and for inspiration. Get the super story juices owing as your students mix up characters, settings, and plots for their own super story creations. Big Question How can I make interesting stories? This lesson will help students to: WordGirl Words 1. Understand the concepts of character, setting and plot. 2. Learn and use new vocabulary. character 3. Cooperatively work and create a story together. a person within a story Media Resources setting WordGirl, “Becky Knows Best” the place a story takes place Materials plot Three bowls or baskets, for drawing out cards the action or problem within WordGirl Storytelling printable: a story • Characters • Settings • Plot (or obstacles, problems—keep these simple and let students elaborate) Classroom or WordGirl Vocabulary list (Examples include: ignore, colossal, vegetarian, ultimate, and tempt.) Paper Pencil Dictionary Chart Paper Markers Find more games and activities at pbskidsforparents.org Made available by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a private corporation funded by the American people. PBS KIDS and the PBS KIDS Logo are registered trademarks of Public Broadcasting Service. Used with permission. WORDGIRL TM & © Scholastic Inc. All Rights Reserved. -

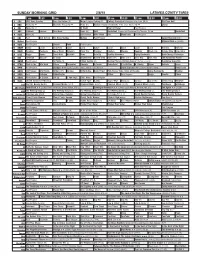

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

The Relations of Parental Acculturation, Parental Mediation, and Children's Educational Television Program Viewing in Immigrant Families Yuting Zhao

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Relations of Parental Acculturation, Parental Mediation, and Children's Educational Television Program Viewing in Immigrant Families Yuting Zhao Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION THE RELATIONS OF PARENTAL ACCULTURATION, PARENTAL MEDIATION, AND CHILDREN’S EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION PROGRAM VIEWING IN IMMIGRANT FAMILIES By YUTING ZHAO A Thesis submitted to the Department of Educational Psychology and Learning Systems in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Yuting Zhao defended this thesis on December 7th, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Beth M. Phillips Professor Directing Thesis Alysia D. Roehrig Committee Member Yanyun Yang Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... vii -

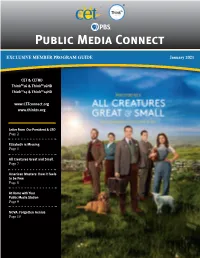

January 2021 EXCLUSIVE MEMBER PROGRAM GUIDE

EXCLUSIVE MEMBER PROGRAM GUIDE January 2021 CET & CETHD ThinkTV16 & ThinkTV16HD ThinkTV14 & ThinkTV14HD www.CETconnect.org www.thinktv.org Letter From Our President & CEO Page 2 Elizabeth is Missing Page 5 All Creatures Great and Small Page 7 American Masters: How it Feels to be Free Page 8 At Home with Your Public Media Station Page 9 NOVA: Forgotten Genius Page 10 JAN 2021 Connect-Fnl.indd 1 12/1/20 10:52 AM Welcome Dear Member, Happy New Year! As we continue to experience the pandemic in our communities, we hope and trust that 2021 will bring health, normalcy and new opportunities to you and your families. As we look back at 2020 and the adversity the pandemic created, we are reminded that it also created opportunities for us to rise to the occasion. It taught us to embrace technology, think outside the box to create fresh content and do more to serve our educators and students. ThinkTV and CET are grateful for the strong community support we received in 2020. Your support allows us to produce local arts and culture programs while pursuing educational initiatives that better serve our communities. We couldn’t do our work without you, so thank you. Of course the great work doesn’t stop. As I write, we are working on a documentary about Ohio women during the Suffrage movement; we are working on the second part of The Dayton Arcade: Waking the Giant; we continue to work with our art and performance partners to help provide a stage for their works; we continue our work on our weekly arts and cultural shows and we will begin working on projects around diversity, racism and inclusion. -

February 2020

TV & RADIO LISTINGS GUIDE FEBRUARY 2020 PRIMETIME For more information go to witf.org/tv WITF honors the legacy of Black History Month with special • programming including the American Masters premiere of Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool. This deep dive into the world of a beloved musical giant features a mix of never before seen footage and new interviews with Quincy Jones, Carlos Santana, Clive Davis, Wayne Shorter, Marcus Miller, Ron Carter, family members and others. The film’s producers were granted access to the Miles Davis estate providing a great depth of material to utilize in this two-hour documentary airing February 25 at 9pm. Fans of Death in Paradise rejoice! The series will continue to solve crimes on a weekly basis for several more months ahead. Season 7 wraps this month, but Season 8 returns in March. Season 9 is currently airing on BBC in the United Kingdom. The brand-new season travels across the pond and lands on the WITF schedule this summer. I had the opportu- nity to see some of the first images from SERIES MARATHON the new season and it looks like there are some changes in store! I don’t want to HOWARDS END ON MASTERPIECE give anything away, so I’ll keep it vague until we get closer to the premiere of the FEBRUARY 2 • 4–9pm new season. In the meantime, the series continues Thursdays at 9pm. Doc Martin Season 8 concludes this Do you have a Smart TV? If you do, through broadcast, cable, satellite or the month. I’m hopeful to bring you Season WITF is now also available on internet, we’re proud to be your neighbor- 9 with Martin and Louisa in early 2021.