The Angular Momentum Energy Equation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fluid Mechanics

FLUID MECHANICS PROF. DR. METİN GÜNER COMPILER ANKARA UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL MACHINERY AND TECHNOLOGIES ENGINEERING 1 1. INTRODUCTION Mechanics is the oldest physical science that deals with both stationary and moving bodies under the influence of forces. Mechanics is divided into three groups: a) Mechanics of rigid bodies, b) Mechanics of deformable bodies, c) Fluid mechanics Fluid mechanics deals with the behavior of fluids at rest (fluid statics) or in motion (fluid dynamics), and the interaction of fluids with solids or other fluids at the boundaries (Fig.1.1.). Fluid mechanics is the branch of physics which involves the study of fluids (liquids, gases, and plasmas) and the forces on them. Fluid mechanics can be divided into two. a)Fluid Statics b)Fluid Dynamics Fluid statics or hydrostatics is the branch of fluid mechanics that studies fluids at rest. It embraces the study of the conditions under which fluids are at rest in stable equilibrium Hydrostatics is fundamental to hydraulics, the engineering of equipment for storing, transporting and using fluids. Hydrostatics offers physical explanations for many phenomena of everyday life, such as why atmospheric pressure changes with altitude, why wood and oil float on water, and why the surface of water is always flat and horizontal whatever the shape of its container. Fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that deals with fluid flow— the natural science of fluids (liquids and gases) in motion. It has several subdisciplines itself, including aerodynamics (the study of air and other gases in motion) and hydrodynamics (the study of liquids in motion). -

Fluid Mechanics

cen72367_fm.qxd 11/23/04 11:22 AM Page i FLUID MECHANICS FUNDAMENTALS AND APPLICATIONS cen72367_fm.qxd 11/23/04 11:22 AM Page ii McGRAW-HILL SERIES IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING Alciatore and Histand: Introduction to Mechatronics and Measurement Systems Anderson: Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Basics with Applications Anderson: Fundamentals of Aerodynamics Anderson: Introduction to Flight Anderson: Modern Compressible Flow Barber: Intermediate Mechanics of Materials Beer/Johnston: Vector Mechanics for Engineers Beer/Johnston/DeWolf: Mechanics of Materials Borman and Ragland: Combustion Engineering Budynas: Advanced Strength and Applied Stress Analysis Çengel and Boles: Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach Çengel and Cimbala: Fluid Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications Çengel and Turner: Fundamentals of Thermal-Fluid Sciences Çengel: Heat Transfer: A Practical Approach Crespo da Silva: Intermediate Dynamics Dieter: Engineering Design: A Materials & Processing Approach Dieter: Mechanical Metallurgy Doebelin: Measurement Systems: Application & Design Dunn: Measurement & Data Analysis for Engineering & Science EDS, Inc.: I-DEAS Student Guide Hamrock/Jacobson/Schmid: Fundamentals of Machine Elements Henkel and Pense: Structure and Properties of Engineering Material Heywood: Internal Combustion Engine Fundamentals Holman: Experimental Methods for Engineers Holman: Heat Transfer Hsu: MEMS & Microsystems: Manufacture & Design Hutton: Fundamentals of Finite Element Analysis Kays/Crawford/Weigand: Convective Heat and Mass Transfer Kelly: Fundamentals -

Thermodynamics of Spacetime: the Einstein Equation of State

gr-qc/9504004 UMDGR-95-114 Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State Ted Jacobson Department of Physics, University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-4111, USA [email protected] Abstract The Einstein equation is derived from the proportionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat, entropy, and temperature. The key idea is to demand that this relation hold for all the local Rindler causal horizons through each spacetime point, with δQ and T interpreted as the energy flux and Unruh temperature seen by an accelerated observer just inside the horizon. This requires that gravitational lensing by matter energy distorts the causal structure of spacetime in just such a way that the Einstein equation holds. Viewed in this way, the Einstein equation is an equation of state. This perspective suggests that it may be no more appropriate to canonically quantize the Einstein equation than it would be to quantize the wave equation for sound in air. arXiv:gr-qc/9504004v2 6 Jun 1995 The four laws of black hole mechanics, which are analogous to those of thermodynamics, were originally derived from the classical Einstein equation[1]. With the discovery of the quantum Hawking radiation[2], it became clear that the analogy is in fact an identity. How did classical General Relativity know that horizon area would turn out to be a form of entropy, and that surface gravity is a temperature? In this letter I will answer that question by turning the logic around and deriving the Einstein equation from the propor- tionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat Q, entropy S, and temperature T . -

Lecture 1: Introduction

Lecture 1: Introduction E. J. Hinch Non-Newtonian fluids occur commonly in our world. These fluids, such as toothpaste, saliva, oils, mud and lava, exhibit a number of behaviors that are different from Newtonian fluids and have a number of additional material properties. In general, these differences arise because the fluid has a microstructure that influences the flow. In section 2, we will present a collection of some of the interesting phenomena arising from flow nonlinearities, the inhibition of stretching, elastic effects and normal stresses. In section 3 we will discuss a variety of devices for measuring material properties, a process known as rheometry. 1 Fluid Mechanical Preliminaries The equations of motion for an incompressible fluid of unit density are (for details and derivation see any text on fluid mechanics, e.g. [1]) @u + (u · r) u = r · S + F (1) @t r · u = 0 (2) where u is the velocity, S is the total stress tensor and F are the body forces. It is customary to divide the total stress into an isotropic part and a deviatoric part as in S = −pI + σ (3) where tr σ = 0. These equations are closed only if we can relate the deviatoric stress to the velocity field (the pressure field satisfies the incompressibility condition). It is common to look for local models where the stress depends only on the local gradients of the flow: σ = σ (E) where E is the rate of strain tensor 1 E = ru + ruT ; (4) 2 the symmetric part of the the velocity gradient tensor. The trace-free requirement on σ and the physical requirement of symmetry σ = σT means that there are only 5 independent components of the deviatoric stress: 3 shear stresses (the off-diagonal elements) and 2 normal stress differences (the diagonal elements constrained to sum to 0). -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

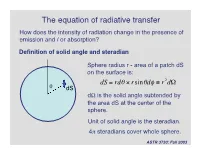

The Equation of Radiative Transfer How Does the Intensity of Radiation Change in the Presence of Emission and / Or Absorption?

The equation of radiative transfer How does the intensity of radiation change in the presence of emission and / or absorption? Definition of solid angle and steradian Sphere radius r - area of a patch dS on the surface is: dS = rdq ¥ rsinqdf ≡ r2dW q dS dW is the solid angle subtended by the area dS at the center of the † sphere. Unit of solid angle is the steradian. 4p steradians cover whole sphere. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Definition of the specific intensity Construct an area dA normal to a light ray, and consider all the rays that pass through dA whose directions lie within a small solid angle dW. Solid angle dW dA The amount of energy passing through dA and into dW in time dt in frequency range dn is: dE = In dAdtdndW Specific intensity of the radiation. † ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Compare with definition of the flux: specific intensity is very similar except it depends upon direction and frequency as well as location. Units of specific intensity are: erg s-1 cm-2 Hz-1 steradian-1 Same as Fn Another, more intuitive name for the specific intensity is brightness. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Simple relation between the flux and the specific intensity: Consider a small area dA, with light rays passing through it at all angles to the normal to the surface n: n o In If q = 90 , then light rays in that direction contribute zero net flux through area dA. q For rays at angle q, foreshortening reduces the effective area by a factor of cos(q). -

Area of Polygons and Complex Figures

Geometry AREA OF POLYGONS AND COMPLEX FIGURES Area is the number of non-overlapping square units needed to cover the interior region of a two- dimensional figure or the surface area of a three-dimensional figure. For example, area is the region that is covered by floor tile (two-dimensional) or paint on a box or a ball (three- dimensional). For additional information about specific shapes, see the boxes below. For additional general information, see the Math Notes box in Lesson 1.1.2 of the Core Connections, Course 2 text. For additional examples and practice, see the Core Connections, Course 2 Checkpoint 1 materials or the Core Connections, Course 3 Checkpoint 4 materials. AREA OF A RECTANGLE To find the area of a rectangle, follow the steps below. 1. Identify the base. 2. Identify the height. 3. Multiply the base times the height to find the area in square units: A = bh. A square is a rectangle in which the base and height are of equal length. Find the area of a square by multiplying the base times itself: A = b2. Example base = 8 units 4 32 square units height = 4 units 8 A = 8 · 4 = 32 square units Parent Guide with Extra Practice 135 Problems Find the areas of the rectangles (figures 1-8) and squares (figures 9-12) below. 1. 2. 3. 4. 2 mi 5 cm 8 m 4 mi 7 in. 6 cm 3 in. 2 m 5. 6. 7. 8. 3 units 6.8 cm 5.5 miles 2 miles 8.7 units 7.25 miles 3.5 cm 2.2 miles 9. -

Right Triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem Related?

Activity Assess 9-6 EXPLORE & REASON Right Triangles and Consider △ ABC with altitude CD‾ as shown. the Pythagorean B Theorem D PearsonRealize.com A 45 C 5√2 I CAN… prove the Pythagorean Theorem using A. What is the area of △ ABC? Of △ACD? Explain your answers. similarity and establish the relationships in special right B. Find the lengths of AD‾ and AB‾ . triangles. C. Look for Relationships Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ ABC VOCABULARY by the length of one of its sides. Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ACD by the length of one of its sides. Make a conjecture that explains • Pythagorean triple the results. ESSENTIAL QUESTION How are similarity in right triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem related? Remember that the Pythagorean Theorem and its converse describe how the side lengths of right triangles are related. THEOREM 9-8 Pythagorean Theorem If a triangle is a right triangle, If... △ABC is a right triangle. then the sum of the squares of the B lengths of the legs is equal to the square of the length of the hypotenuse. c a A C b 2 2 2 PROOF: SEE EXAMPLE 1. Then... a + b = c THEOREM 9-9 Converse of the Pythagorean Theorem 2 2 2 If the sum of the squares of the If... a + b = c lengths of two sides of a triangle is B equal to the square of the length of the third side, then the triangle is a right triangle. c a A C b PROOF: SEE EXERCISE 17. Then... △ABC is a right triangle. -

Calculus Formulas and Theorems

Formulas and Theorems for Reference I. Tbigonometric Formulas l. sin2d+c,cis2d:1 sec2d l*cot20:<:sc:20 +.I sin(-d) : -sitt0 t,rs(-//) = t r1sl/ : -tallH 7. sin(A* B) :sitrAcosB*silBcosA 8. : siri A cos B - siu B <:os,;l 9. cos(A+ B) - cos,4cos B - siuA siriB 10. cos(A- B) : cosA cosB + silrA sirrB 11. 2 sirrd t:osd 12. <'os20- coS2(i - siu20 : 2<'os2o - I - 1 - 2sin20 I 13. tan d : <.rft0 (:ost/ I 14. <:ol0 : sirrd tattH 1 15. (:OS I/ 1 16. cscd - ri" 6i /F tl r(. cos[I ^ -el : sitt d \l 18. -01 : COSA 215 216 Formulas and Theorems II. Differentiation Formulas !(r") - trr:"-1 Q,:I' ]tra-fg'+gf' gJ'-,f g' - * (i) ,l' ,I - (tt(.r))9'(.,') ,i;.[tyt.rt) l'' d, \ (sttt rrJ .* ('oqI' .7, tJ, \ . ./ stll lr dr. l('os J { 1a,,,t,:r) - .,' o.t "11'2 1(<,ot.r') - (,.(,2.r' Q:T rl , (sc'c:.r'J: sPl'.r tall 11 ,7, d, - (<:s<t.r,; - (ls(].]'(rot;.r fr("'),t -.'' ,1 - fr(u") o,'ltrc ,l ,, 1 ' tlll ri - (l.t' .f d,^ --: I -iAl'CSllLl'l t!.r' J1 - rz 1(Arcsi' r) : oT Il12 Formulas and Theorems 2I7 III. Integration Formulas 1. ,f "or:artC 2. [\0,-trrlrl *(' .t "r 3. [,' ,t.,: r^x| (' ,I 4. In' a,,: lL , ,' .l 111Q 5. In., a.r: .rhr.r' .r r (' ,l f 6. sirr.r d.r' - ( os.r'-t C ./ 7. /.,,.r' dr : sitr.i'| (' .t 8. tl:r:hr sec,rl+ C or ln Jccrsrl+ C ,f'r^rr f 9. -

Chapter 3 Newtonian Fluids

CM4650 Chapter 3 Newtonian Fluid 2/5/2018 Mechanics Chapter 3: Newtonian Fluids CM4650 Polymer Rheology Michigan Tech Navier-Stokes Equation v vv p 2 v g t 1 © Faith A. Morrison, Michigan Tech U. Chapter 3: Newtonian Fluid Mechanics TWO GOALS •Derive governing equations (mass and momentum balances •Solve governing equations for velocity and stress fields QUICK START V W x First, before we get deep into 2 v (x ) H derivation, let’s do a Navier-Stokes 1 2 x1 problem to get you started in the x3 mechanics of this type of problem solving. 2 © Faith A. Morrison, Michigan Tech U. 1 CM4650 Chapter 3 Newtonian Fluid 2/5/2018 Mechanics EXAMPLE: Drag flow between infinite parallel plates •Newtonian •steady state •incompressible fluid •very wide, long V •uniform pressure W x2 v1(x2) H x1 x3 3 EXAMPLE: Poiseuille flow between infinite parallel plates •Newtonian •steady state •Incompressible fluid •infinitely wide, long W x2 2H x1 x3 v (x ) x1=0 1 2 x1=L p=Po p=PL 4 2 CM4650 Chapter 3 Newtonian Fluid 2/5/2018 Mechanics Engineering Quantities of In more complex flows, we can use Interest general expressions that work in all cases. (any flow) volumetric ⋅ flow rate ∬ ⋅ | average 〈 〉 velocity ∬ Using the general formulas will Here, is the outwardly pointing unit normal help prevent errors. of ; it points in the direction “through” 5 © Faith A. Morrison, Michigan Tech U. The stress tensor was Total stress tensor, Π: invented to make the calculation of fluid stress easier. Π ≡ b (any flow, small surface) dS nˆ Force on the S ⋅ Π surface V (using the stress convention of Understanding Rheology) Here, is the outwardly pointing unit normal of ; it points in the direction “through” 6 © Faith A. -

The American Society of Echocardiography

1 THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CARDIAC CHAMBER QUANTIFICATION IN ADULTS: A QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE FROM THE ASE WORKFLOW AND LAB MANAGEMENT TASK FORCE Accurate and reproducible assessment of cardiac chamber size and function is essential for clinical care. A standardized methodology creates a common approach to the assessment of cardiac structure and function both within and between echocardiography labs. This facilitates better communication and improves the ability to compare results between studies as well as differentiate normal from abnormal findings in an individual patient. This document summarizes key points from the 2015 ASE Chamber Quantification Guideline and is meant to serve as quick reference for sonographers and interpreting physicians. It is designed to provide guidance on chamber quantification for adult patients; a separate ASE Guidelines document that details recommended quantification methods in the pediatric age group has also been published and should be used for patients <18 years of age (3). (1) For details of the methodology and the rationale for current recommendations, the interested reader is referred to the complete Guideline statement. Figures and tables are reproduced from ASE Guidelines. (1,2) Table of Contents: 1. Left Ventricle (LV) Size and Function p. 2 a. LV Size p. 2 i. Linear Measurements p. 2 ii. Volume Measurements p. 2 iii. LV Mass Calculations p. 3 b. Left Ventricular Function Assessment p. 4 i. Global Systolic Function Parameters p. 4 ii. Regional Function p. 5 2. Right Ventricle (RV) Size and Function p. 6 a. RV Size p. 6 b. RV Function p. 8 3. Atria p. -

Difference Between Angular Momentum and Pseudoangular

Difference between angular momentum and pseudoangular momentum Simon Streib Department of Physics and Astronomy, Uppsala University, Box 516, SE-75120 Uppsala, Sweden (Dated: March 16, 2021) In condensed matter systems it is necessary to distinguish between the momentum of the con- stituents of the system and the pseudomomentum of quasiparticles. The same distinction is also valid for angular momentum and pseudoangular momentum. Based on Noether’s theorem, we demonstrate that the recently discussed orbital angular momenta of phonons and magnons are pseudoangular momenta. This conceptual difference is important for a proper understanding of the transfer of angular momentum in condensed matter systems, especially in spintronics applications. In 1915, Einstein, de Haas, and Barnett demonstrated experimentally that magnetism is fundamentally related to angular momentum. When changing the magnetiza- tion of a magnet, Einstein and de Haas observed that the magnet starts to rotate, implying a transfer of an- (a) gular momentum from the magnetization to the global rotation of the lattice [1], while Barnett observed the in- verse effect, magnetization by rotation [2]. A few years later in 1918, Emmy Noether showed that continuous (b) symmetries imply conservation laws [3], such as the con- servation of momentum and angular momentum, which links magnetism to the most fundamental symmetries of nature. Condensed matter systems support closely related con- Figure 1. (a) Invariance under rotations of the whole system servation laws: the conservation of the pseudomomentum implies conservation of angular momentum, while (b) invari- and pseudoangular momentum of quasiparticles, such as ance under rotations of fields with a fixed background implies magnons and phonons.