Grunge and Blues, a Sociological Comparison: How Space and Place Influence the Development and Spread of Regional Musical Styles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

1 Birthplace of America's Music Tour Tunica, Clarksdale, Cleveland

Birthplace of America’s Music Tour Tunica, Clarksdale, Cleveland, Indianola, Greenwood, Meridian, Hattiesburg Mississippi is widely considered the Birthplace of America’s Music, the one place where visitors can trace the blues, rock ‘n’ roll and country to their roots. This tour follows Highway 61, the “blues highway,” through the Mississippi Delta where the blues originated, and then visits Meridian, home of the father of country music, Jimmie Rogers. There, you’ll tour his namesake museum and the new Mississippi Arts & Entertainment Experience. This tour also visits the interactive GRAMMY Museum® Mississippi, the B.B. King Museum and much more. Thursday, March 15 Southaven to Oxford, MS You'll find "South of the Ordinary" – otherwise known as DeSoto County – in a lovely corner of Northwest Mississippi, just minutes from Memphis, Tennessee. Arrival and Transportation Instructions from Memphis International Airport: Once you have gathered your baggage, please exit the baggage claim area. Look for a friendly face holding a sign imprinted with your name and Visit Desoto County. You will be transported to the Courtyard by Marriott in Southaven, Mississippi. For those of you arriving on Wednesday, March 14, you will receive an additional email with arrival instructions. Your Visit Mississippi escort for this FAM is Paula Travis, and your Visit DeSoto County host is Kim Terrell. Paula’s cell 601-573-6295 Kim’s cell 901-870-3578 Hospitality Suite at Courtyard by Marriott 7225 Sleepy Hollow Drive, Southaven, MS 38671 662-996-1480 3:45pm Meet in lobby with luggage to board bus 4:00 pm Depart Southaven for Tunica 4:30 pm Arrive Tunica Nearby casino gaming attractions only add to the excitement in Tunica, where the U.S. -

A Case Study of Kurt Donald Cobain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) A CASE STUDY OF KURT DONALD COBAIN By Candice Belinda Pieterse Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University December 2009 Supervisor: Prof. J.G. Howcroft Co-Supervisor: Dr. L. Stroud i DECLARATION BY THE STUDENT I, Candice Belinda Pieterse, Student Number 204009308, for the qualification Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology, hereby declares that: In accordance with the Rule G4.6.3, the above-mentioned treatise is my own work and has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. Signature: …………………………………. Date: …………………………………. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several individuals that I would like to acknowledge and thank for all their support, encouragement and guidance whilst completing the study: Professor Howcroft and Doctor Stroud, as supervisors of the study, for all their help, guidance and support. As I was in Bloemfontein, they were still available to meet all my needs and concerns, and contribute to the quality of the study. My parents and Michelle Wilmot for all their support, encouragement and financial help, allowing me to further my academic career and allowing me to meet all my needs regarding the completion of the study. The participants and friends who were willing to take time out of their schedules and contribute to the nature of this study. Konesh Pillay, my friend and colleague, for her continuous support and liaison regarding the completion of this study. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

Jazz in America • the National Jazz Curriculum the Blues and Jazz Test Bank

Jazz in America • The National Jazz Curriculum The Blues and Jazz Test Bank Select the BEST answer. 1. Of the following, the style of music to be considered jazz’s most important influence is A. folk music B. the blues C. country music D. hip-hop E. klezmer music 2. Of the following, the blues most likely originated in A. Alaska B. Chicago C. the Mississippi Delta D. Europe E. San Francisco 3. The blues is A. a feeling B. a particular kind of musical scale and/or chord progression C. a poetic form and/or type of song D. a shared history E. all of the above 4. The number of chords in a typical early blues chord progression is A. three B. four C. five D. eight E. twelve 5. The number of measures in typical blues chorus is A. three B. four C. five D. eight E. twelve 6. The primary creators of the blues were A. Africans B. Europeans C. African Americans D. European Americans E. Asians 7. Today the blues is A. played and listened to primarily by African Americans B. played and listened to primarily by European Americans C. respected more in the United States than in Europe D. not appreciated by people outside the United States E. played and listened to by people all over the world 8. Like jazz, blues is music that is A. planned B. spontaneous C. partly planned and partly spontaneous D. neither planned nor spontaneous E. completely improvised 9. Blues lyrical content A. is usually secular (as opposed to religious) B. -

Hegemony in the Music and Culture of Delta Blues Taylor Applegate [email protected]

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research 2013 The crossroads at midnight: Hegemony in the music and culture of Delta blues Taylor Applegate [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Applegate, Taylor, "The crossroads at midnight: Hegemony in the music and culture of Delta blues" (2013). Summer Research. Paper 208. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/208 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Crossroads at Midnight: Hegemony in the Music and Culture of Delta Blues Taylor Applegate Advisor: Mike Benveniste Summer 2013 INTRODUCTION. Cornel West’s essay “On Afro-American Music: From Bebop to Rap” astutely outlines the developments in Afro-American popular music from bebop and jazz, to soul, to funk, to Motown, to technofunk, to the rap music of today. By taking seriously Afro-American popular music, one can dip into the multileveled lifeworlds of black people. As Ralph Ellison has suggested, Afro-Americans have had rhythmic freedom in place of social freedom, linguistic wealth instead of pecuniary wealth (West 474). And as the fount of all these musical forms West cites “the Afro-American spiritual-blues impulse,” the musical traditions of some of the earliest forms of black music on the American continent (474). The origins of the blues tradition, however, are more difficult to pin down; poor documentation at the time combined with more recent romanticization of the genre makes a clear, chronological explanation like West’s outline of more recent popular music impossible. -

“Late 'Punk Poet' Jim Carroll Had Strong Seattle Music Ties (Part 1 Of

Late 'punk poet' Jim Carroll had strong Seattle music ties (part 1 of 2) 9/21/09 Mon 9/21, 11:57 PM Go mobile | Favorite Examiners | Meet the Examiners Search articles from thousands of Examiners Select your city National Home Entertainment Business Family & Home Life News & Politics Sports & Recreation National Arts and Entertainment Seattle Local Music Examiner Late 'punk poet' Jim Carroll had strong YOUR AD HERE Seattle music ties (part 1 of 2) September 16, 6:54 PM Seattle Local Music Examiner Greg Roth Comment Print Email RSS Subscribe Previous Next Part 1 of a 2 part series (Part 2 will run on Sunday, September 20th)... With, the sad death of Patrick Swayze and the MTV Video Music Awards featuring "Kaynegate", The death of legendary performance artist/singer/songwriter and poet, Jim Carroll, on September 14th, by a sudden heart attack, somehow got lost in the mix in Recent Articles the last few days. Late 'punk poet' / artist Jim Carroll had strong Carroll, who's "no holds barred" style of prose Seattle music ties (part 2 of 2) married with hard edged rock music, garnered Sunday, September 20, 2009 a fiercely loyal following and influenced many Part 2 of a 2 part series, Part 1 or the newer generation of artists today. ran on Wednesday, September 16th... With the death of Patrick Swayze and Kanye West's It could be said that Carroll was hard core rap interruption of Taylor Swift's … before the genre ever officially existed. Carroll Local Licks: Seattle local musical happenings: was an artist years ahead of his time and weekend of: 9/18 - 9/20 used his art to uncover the underbelly of the Saturday, September 19, 2009 human condition during an era, when others As always, there is an invariable chose to look away. -

No. Title Singer a 101 Addicted to Love Robert

No. Title Singer A 101 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer 127 After Midnight Eric Clapton 128 Ain't No Stoppin' Us Now McFadden & Whitehead 1 All I Want Is A Life Tim McGraw 82 All Star Smash Mouth 108 All The Man That I Need Whitney Houston 91 All You Wanted Michelle Branch 40 Always Atlantic Starr 129 Amarillo By Morning George Strait 130 Amie Pure Prairie League 109 And She Was Talking Heads 2 And Still Reba McEntire 8 Anything Goes Frank Sinatra 120 Are You Happy Now Michelle Branch 68 Arthur's Theme (The Best That You..) Christopher Cross 131 At This Moment Billy Vera B 132 Bad Michael Jackson 133 Bang The Drum All Day Todd Rundgren 134 Beat Goes On, The Sonny & Cher 135 Beat It Michael Jackson 41 Behind Closed Doors Charlie Rich 136 Big Spender from "Sweet Charity" 137 Billie Jean Michael Jackson 104 Black Or White Michael Jackson 138 Black Water Doobie Brothers 139 Brandy You're a Fine Girl Looking Glass 122 Breathe Michelle Branch 7 But I Will Faith Hill C 140 Candy Man Roy Orbison 141 Can't Get Enough (of Your Love) Bad Company 142 Can't Get Enough of Your Love Babe Barry White 87 Careless Whisper Wham 124 Carried Away George Strait 11 Carrying Your Love With Me George Strait 93 Celebration Kool And The Gang 143 Chain Of Fools Aretha Franklin 61 Cherish Kool And The Gang 76 Closing Time Semisonic 60 Copperhead Road Steve Earle 144 Could It Be I'm Falling in Love? Spinners, The 98 Crazy For You Madonna D 27 Dance To The Music Sly & The Family Stone 145 December Collective Soul E 42 Embraceable You Nat King Cole 105 Endless Love Diana Ross/Lionel Richie 146 Escape (The Pina Colada Song) Rupert Holmes 43 Evergreen Barbra Streisand 147 Everybody Hurts R.E.M. -

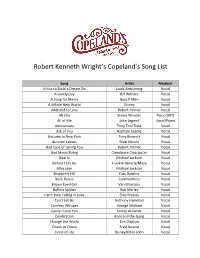

Robert Kenneth Wright's Copeland's Song List

Robert Kenneth Wright’s Copeland’s Song List Song Artist Medium A Kiss to Build a Dream On Louis Armstrong Vocal A Lovely Day Bill Withers Vocal A Song for Mama Boyz II Men Vocal A Whole New World Disney Vocal Addicted to Love Robert Palmer Vocal All I Do Stevie Wonder Piano (WT) All of Me John Legend Vocal/Piano Anniversary Tony Toni Tone Vocal Ask of You Raphael Saadiq Vocal Autumn in New York Tony Bennett Vocal Autumn Leaves Matt Monro Vocal Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Vocal Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Vocal Beat It Michael Jackson Vocal Before I Let Go Frankie Beverly/Maze Vocal Billie Jean Michael Jackson Vocal Blueberry Hill Fats Domino Vocal Brick House Commodores Vocal Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Vocal Buffalo Soldier Bob Marley Vocal Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Vocal Can’t Let Go Anthony Hamilton Vocal Careless Whisper George Michael Vocal Cause I Love You Lenny Williams Vocal Celebration Kool and the Gang Vocal Change the World Eric Clapton Vocal Cheek to Cheek Fred Astaire Vocal Circle of Life Disney/Elton John Vocal Close the Door Teddy Pendergrass Vocal Cold Sweat James Brown Vocal Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Vocal Creepin’ Luther Vandross Vocal Dat Dere Tony Bennett Vocal Distant Lover Marvin Gaye Vocal Don’t Stop Believing Journey Vocal Don’t Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Vocal Don’t You Know That Luther Vandross Vocal Early in the Morning Gap Band Vocal End of the Road Boyz II Men Vocal Every Breath You Take The Police Vocal Feelin’ on Ya Booty R. -

The Devil in Robert Johnson: the Progression of the Delta Blues to Rock and Roll by Adam Compagna

The Devil in Robert Johnson: The Progression of the Delta Blues to Rock and Roll by Adam Compagna “I went down to the crossroads, fell down on my knees, I went down to the crossroads, fell down on my knees, Saw the Devil and begged for mercy, help me if you please --- Crearn, “Crossroads” With the emergence of rock and roll in the late nineteen fifties and early nineteen sixties, many different sounds and styles of music were being heard by the popular audience. These early rock musicians blended the current pop style with the non-mainstream rhythm and blues sound that was prevalent mainly in the African-American culture. Later on in the late sixties, especially during the British “invasion,” such bands as the Beatles, Cream, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, and the Yardbirds used this blues style and sound in their music and marketed it to a different generation. This blues music was very important to the evolution of rock and roll, but more importantly, where did this blues influence come from and why was it so important? The answer lies in the Mississippi Delta at the beginning of the twentieth century, down at the crossroads. From this southern section of America many important blues men, including Robert Johnson, got their start in the late nineteen twenties. A man who supposedly sold his soul to the Devil for the ability to play the guitar, Robert Johnson was a main influence on early rock musicians not only for his stylistic guitar playing but also for his poetic lyrics. 1 An important factor in the creation of the genre of the Delta blues is the era that these blues men came from. -

In the Studio: the Role of Recording Techniques in Rock Music (2006)

21 In the Studio: The Role of Recording Techniques in Rock Music (2006) John Covach I want this record to be perfect. Meticulously perfect. Steely Dan-perfect. -Dave Grohl, commencing work on the Foo Fighters 2002 record One by One When we speak of popular music, we should speak not of songs but rather; of recordings, which are created in the studio by musicians, engineers and producers who aim not only to capture good performances, but more, to create aesthetic objects. (Zak 200 I, xvi-xvii) In this "interlude" Jon Covach, Professor of Music at the Eastman School of Music, provides a clear introduction to the basic elements of recorded sound: ambience, which includes reverb and echo; equalization; and stereo placement He also describes a particularly useful means of visualizing and analyzing recordings. The student might begin by becoming sensitive to the three dimensions of height (frequency range), width (stereo placement) and depth (ambience), and from there go on to con sider other special effects. One way to analyze the music, then, is to work backward from the final product, to listen carefully and imagine how it was created by the engineer and producer. To illustrate this process, Covach provides analyses .of two songs created by famous producers in different eras: Steely Dan's "Josie" and Phil Spector's "Da Doo Ron Ron:' Records, tapes, and CDs are central to the history of rock music, and since the mid 1990s, digital downloading and file sharing have also become significant factors in how music gets from the artists to listeners. Live performance is also important, and some groups-such as the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers Band, and more recently Phish and Widespread Panic-have been more oriented toward performances that change from night to night than with authoritative versions of tunes that are produced in a recording studio. -

Understand the Past, See the Future, & Make an Impact

Mississippi Delta 2012 Mississippi State University Understand the past, see the future, & make an impact... TABLE OF CONTENTS Emergency Contacts & Rules and Reminders............................................................ 1 List of Groups - Breakfast/Clean Up Teams & Service Teams.................................. 2 Alternative Spring Break Map....................................................................................3 Sunday Itinerary.......................................................................................................... 4 North Greenwood Baptist Church...............................................................................5 Mississippians Engaged in Greener Agriculture (MEGA)......................................... 6 LEAD Center - Sunflower County Freedom Project.................................................. 7 The Help......................................................................................................................8 Monday Itinerary.........................................................................................................9 Dr. Luther Brown - Delta Heritage Tour.....................................................................10 Chinese Mission School..............................................................................................11 Dockery Farms.............................................................................................................12 Fannie Lou Hamer.......................................................................................................14