Collaborative Approach for Developing a More Effective Regional Planning Framework in Egypt: Ecotourism Development As Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharaonic Egypt Through the Eyes of a European Traveller and Collector

Pharaonic Egypt through the eyes of a European traveller and collector Excerpts from the travel diary of Johann Michael Wansleben (1672-3), with an introduction and annotations by Esther de Groot Esther de Groot s0901245 Book and Digital Media Studies University of Leiden First Reader: P.G. Hoftijzer Second reader: R.J. Demarée 0 1 2 Pharaonic Egypt through the eyes of a European traveller and collector Excerpts from the travel diary of Johann Michael Wansleben (1672-3), with an introduction and annotations by Esther de Groot. 3 4 For Harold M. Hays 1965-2013 Who taught me how to read hieroglyphs 5 6 Contents List of illustrations p. 8 Introduction p. 9 Editorial note p. 11 Johann Michael Wansleben: A traveller of his time p. 12 Egypt in the Ottoman Empire p. 21 The journal p. 28 Travelled places p. 53 Acknowledgments p. 67 Bibliography p. 68 Appendix p. 73 7 List of illustrations Figure 1. Giza, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 104 p. 54 Figure 2. The pillar of Marcus Aurelius, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 123 p. 59 Figure 3. Satellite view of Der Abu Hennis and Der el Bersha p. 60 Figure 4. Map of Der Abu Hennis from the original manuscript p. 61 Figure 5. Map of the visited places in Egypt p. 65 Figure 6. Map of the visited places in the Faiyum p. 66 Figure 7. An offering table from Saqqara, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 39 p. 73 Figure 8. A stela from Saqqara, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 40 p. 74 Figure 9. -

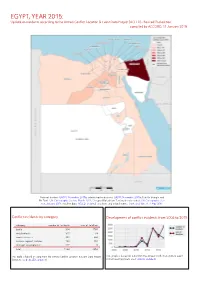

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Pollen Atlas of the Flora of Egypt 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae

Pollen Atlas of the flora of Egypt * 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae Nahed El-Husseini and Eman Shamso. The Herbarium, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza 12613, Egypt. El-Husseini, N. & Shamso, E. 2002. The pollen atlas of the flora of Egypt. 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae. Taeckholmia 22(1): 65-76. Light and scanning electron microscope study of the pollen grains of 47 species representing 16 genera of Scrophulariaceae in Egypt was carried out. Pollen grains vary from subspheroidal to prolate; trizonocolpate to trizonocolporate. Exine’s sculpture is striate, colliculate, granulate, coarse reticulate or microreticulate. Seven pollen types are recognized and briefly described, a key distinguishing the different pollen types and the discussion of its systematic value are provided. Key words: Flora of Egypt, pollen atlas, Scrophulariaceae. Introduction The Scrophulariaceae is a family of about 292 genera and nearly 3000 species of cosmopolitan distribution. It is represented in the flora of Egypt by 50 species belonging to 16 genera, 8 tribes and 3 sub-families (El-Hadidi et al., 1999). Within the family, a wide range of pollen morphology exists and provides not only an additional parameter for generic delimitation but also reinforces the validity of many of the larger taxa. Erdtman (1952), gave a concise account of the pollen morphology of some members of the family. Several authors studied and described the pollen of species of the family among whom to mention: Risch (1939), Ikuse (1956), Natarajan (1957), Verghese (1968), Olsson (1974), Elisens (1985c & 1986), Bolliger & Wick (1990) and Argu (1980, 1990 & 1993). Material and Methods Pollen grains of 47 species representing 16 genera of Scrophulariaceae were the subject of the present investigation. -

Egypt Revisited “It Was an Amazing Experience to See Such Wonderful Sites Enhanced by Our Lecturer’S Knowledge...A Fabulous Experience!”

Limited to just 16 guests EGYPT Revisited “It was an amazing experience to see such wonderful sites enhanced by our lecturer’s knowledge...A fabulous experience!” - Barbara, Maryland Foreground, Red Pyramid at Dahshur; background, Temple of Seti I at Abydos October 19-November 3, 2019 (16 days | 16 guests) with Egyptologist Stephen Harvey optional extensions: pre-tour Siwa Oasis & Alexandria (8 days) and/or post-tour Jordan (5 days) Archaeology-focused tours for the curious to the connoisseur. Dear Traveler, You are invited to return to Egypt on a brand-new, custom-designed tour in the company of AIA lecturer/host Stephen Harvey, Egyptology guide Enass Salah, and a professional tour manager. © Ivrienen Snefru's Bent Pyramid at Dahshur Highlights are many and varied: • Gain inside access to the Red Pyramid at Dahshur, enter the burial chamber of the collapsed pyramid at Meidum, and visit two mud-brick pyramids (Illahun and Hawara) at the Fayoum Oasis. • Go behind-the-scenes at the ancient necropolis of Saqqara to see some of the new and remarkable excavations that are not open to the public, including (pending final confirmation) special access to the newly- discovered, 5th-dynasty Tomb of Wah Ti. • Make a special, private visit (permission pending) to the new Grand Egyptian Museum. • Explore the necropoli of Beni Hasan, known for its 39 rock-cut tombs © Olaf Tausch with well-preserved paintings of dancing, acrobatics, juggling, fishing, Red Pyramid at Dahshur hunting, and weaving; and Tuna el-Gebel, with huge catacombs for thousands of mummified ibises and baboons, and much more. • Visit Tell el-Amarna, which replaced Thebes (modern Luxor) as capital of Egypt under the heretic, 18th-dynasty pharaoh Akhenaton and was significant for its monotheism and distinctive artistic style. -

FAYOUM OASIS BETWEEN PROBLEMS and POTENTIALS: TOWARDS ENHANCING ECOTOURISM in EGYPT Marwa A

URBENVIRON CAIRO 2011 4th International Congress on Environmental Planning and Management Green Cities: A Path to Sustainability December 10 – 13, 2011 Cairo and El-Gouna, Egypt FAYOUM OASIS BETWEEN PROBLEMS AND POTENTIALS: TOWARDS ENHANCING ECOTOURISM IN EGYPT Marwa A. Khalifa1&Samah M. El-Khateeb2 1Assistant Professor at the Department of Planning and Urban Design, Faculty of Engineering – Ain Shams University. 1 Elsarayat St. Abbasy, Cairo – Egypt. Email: [email protected] 1 Assistant Professor at the Department of Planning and Urban Design, Faculty of Engineering – Ain Shams University. 1 Elsarayat St. Abbasy, Cairo – Egypt. Email: [email protected] Ecotourism though in comparison to other types of tourism, it is a small but rapidly growing movement.It is in the core of the tourism development strategy in Egypt and there is considerable effort to promote such type of tourism.Fayoum oasis is foreseen to be one of the major destination for ecotourism not only in Egypt but also worldwide. It isone of the most wonderful areasin Egypt, which contains much potential for ecotourism, asit is rich in natural resources and interesting history.It contains three major protected areas;QarounLake,El-RayanValley and Whale Valley protectorates. The last onewas designated as a UNISCO World Heritage Site owing to the important 40 millions year-old whale skeletons found there.Although the uniqueness of Fayoum, it does not occupy a significant position on the touristic map of Egypt. This paper is an attempt to highlight the major potentials in the Fayoum oasis as well as theproblemsand obstacles that preclude its development. It analyzesthe factors that lead to the declining of the tourism industry in the oasis andproposes a vision for developing the oasis to be one of the major destinations of ecotourism in Egypt as well as worldwide. -

10 Day Tour Package from Marsa Alam

MARSA ALAM TOURS 00201001058227 [email protected] 10 day tour package from Marsa Alam Type Run Duration Pick up Private Every Day 10 days 01:00 Are you looking for amazing tour packages from Marsa Alam to discover the beauty of Egypt? with our 10-day tour Package from Marsa Alam. you can see Egypt Highlights, like the Pyramids of Giza, Cairo Museum,The white desert. Abu Simble temples. Inclusions: Exclusions: All transfers mentioned in the Any Extras not mentioned in the above itinerary itinerary Flight ticket [ Marsa Alam/ Cairo - Tipping Cairo / Aswan ]. All transfers by a private air- conditioned vehicle. English Tour guide, language as required. 2 Night in Le Meridien Pyramids 1 Night in the white desert 1 Night in wadi el Hitan 2 Nights in Basma Hotel 2 Nights in Nile Palace Hotel Lunch meals during the tours. Entrance fees for the mentioned sightseeing Lunch during excursions Private transfer from Luxor to Marsa Alam All Service charges & taxes Itinerary: Are you looking for amazing tour packages from Marsa Alam to discover the beauty of Egypt? with our 10-day tour Package from Marsa Alam. you can see Egypt Highlights, like the Pyramids of Giza, Cairo Museum,The white desert. Abu Simble temples, The valley of the kings, book now online your tour Package from Marsa Alam. page 1 / 7 MARSA ALAM TOURS 00201001058227 [email protected] Days Table First Day :Day 1- Marsa Alam- Cairo We will pick you up from your hotel in Marsa Alam to transfer to Marsa Alam airport.,The flight leaves from Marsa Alam at 5:00 AM and arrives at 06.00 at Cairo airport where you will be met and assisted by our representative. -

Meet Our New Mes Cairo Teachers

Contents Whole School Principal Foreword 3 American Section Student of the Month and 52 British Section MES All Stars Graduation Ceremony 4 Staff Professional Development 53 American Section Results 7 Primary Science Week 54 British Section Results 8 Foundation Stage One Induction Day 56 IBDP Results 10 Foundation Stage Two 57 UK Universities Update 11 Year One 58 British Section Scholarship Winner 12 Year Two 59 American Section Scholarship Winner 13 Year Three 60 IBDP Section Scholarship Winner 14 Year Four 61 IBDP News and CAS Residential 15 Year Five Concert 62 MEIBA and IBDP Jobalike Event 21 Year Six Leaver’s Day 63 WIRED and Going Google 22 Primary Sportsdesk 64 Digital Citizenship 24 Primary ASAs 67 American Section Science Update 26 Primary Pioneer Programme 68 Grade Seven and Eight Fagnoon Trip 28 Secondary Pioneer Programme 69 Grade Seven and Nine Back to School 29 Nights International Award News 70 HRCF and Grade Nine Escape Rooms 30 Secondary ASAs 71 Grade Ten Poetry Slam 31 MES Cairo Achievers 72 British Section Transition Day 32 Lara Majid’s New York Internship 73 British Section Maths Update 33 NHS/NJHS Induction Ceremony 74 Year Seven ToTAL News 35 Secondary Sportsdesk 75 Year Eight News 36 MES Cairo Welcomes New Teachers 82 Year Nine News 37 Halloween Happiness 90 Humanities News 39 MESConians – Where Are They Now? 91 Year Eight – Ahmed Zewail Day 40 Remembrance Day 92 Creative Arts News 41 MES Cairo Ladies Pharaonic Run and Sahl 93 Hasheesh Triathlon Evita Spoiler 47 MES Cairo New Births, Cairo Opera House 94 HRCF Middle School Madness 48 and Breast Cancer Awareness HRCF Motivated Mentors 49 MESMerised 95 Secondary House News 50 2 WHOLE SCHOOL PRINCIPAL FOREWORD pace and purpose of a term at our school school. -

2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Wadi Al-Hitan (Whale Valley) - 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment Wadi Al-Hitan (Whale Valley) 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment SITE INFORMATION Country: Egypt Inscribed in: 2005 Criteria: (viii) Wadi Al-Hitan, Whale Valley, in the Western Desert of Egypt, contains invaluable fossil remains of the earliest, and now extinct, suborder of whales, Archaeoceti. These fossils represent one of the major stories of evolution: the emergence of the whale as an ocean-going mammal from a previous life as a land-based animal. This is the most important site in the world for the demonstration of this stage of evolution. It portrays vividly the form and life of these whales during their transition. The number, concentration and quality of such fossils here is unique, as is their accessibility and setting in an attractive and protected landscape. The fossils of Al-Hitan show the youngest archaeocetes, in the last stages of losing their hind limbs. Other fossil material in the site makes it possible to reconstruct the surrounding environmental and ecological conditions of the time. © UNESCO SUMMARY 2020 Conservation Outlook Finalised on 01 Dec 2020 GOOD The conservation outlook for Wadi Al-Hitan is good overall. Wadi Al-Hitan comprises exceptionally rich values related to the record of life, and these are generally in a very good state of conservation. An appropriate management framework is in place through the updated 2019 Wadi El-Rayan Protected Area including Wadi Al-Hitan as a separate component within its program of action. The management unit still needs to develop a site-level plan for Wadi Al-Hitan within the main management plan document, including its own site maps. -

Stomach Contents of the Archaeocete Basilosaurus Isis: Apex Predator in Oceans of the Late Eocene

RESEARCH ARTICLE Stomach contents of the archaeocete Basilosaurus isis: Apex predator in oceans of the late Eocene 1☯ 2³ 3³ 3☯ Manja VossID *, Mohammed Sameh M. Antar , Iyad S. Zalmout , Philip D. Gingerich 1 Museum fuÈr Naturkunde Berlin, Leibniz-Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, Berlin, Germany, 2 Department of Geology and Paleontology, Nature Conservation Sector, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency, Cairo, Egypt, 3 Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States of America a1111111111 a1111111111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. a1111111111 ³ These authors also contributed equally to this work. a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 Abstract Apex predators live at the top of an ecological pyramid, preying on animals in the pyramid OPEN ACCESS below and normally immune from predation themselves. Apex predators are often, but not Citation: Voss M, Antar MSM, Zalmout IS, always, the largest animals of their kind. The living killer whale Orcinus orca is an apex pred- Gingerich PD (2019) Stomach contents of the ator in modern world oceans. Here we focus on an earlier apex predator, the late Eocene archaeocete Basilosaurus isis: Apex predator in oceans of the late Eocene. PLoS ONE 14(1): archaeocete Basilosaurus isis from Wadi Al Hitan in Egypt, and show from stomach con- e0209021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. tents that it fed on smaller whales (juvenile Dorudon atrox) and large fishes (Pycnodus pone.0209021 mokattamensis). Our observations, the first direct evidence of diet in Basilosaurus isis, con- Editor: Carlo Meloro, Liverpool John Moores firm a predator-prey relationship of the two most frequently found fossil whales in Wadi Al- University, UNITED KINGDOM Hitan, B. -

Wadi El Rayan Protectorate Features a Notable 12EL RAYAN UNESCO World Heritage Site

ECO EGYPT Experiences is a campaign that aims to reconnect adventurous trav- ellers with Egypt’s countless ecological sites and protected areas. With the goal of prompting natural rediscovery and boosting the importance of ecological con- servation, the ECO EGYPT Experiences campaign sheds light on all the wildlife, plant diversity, and natural landscapes on offer throughout Egypt. The campaign encourages sustainable, responsible tourism for travellers seeking unique, out-of- the-box experiences. By centering the voices, experiences, and customs of local tribespeople, from Nubians to Bedouins, ECO EGYPT advocates support for local livelihoods by giving a platform for the unique practices, traditions, and crafts of local communities. From camping to diving, stargazing to birdwatching, Egypt’s ecological sites promise unparalleled experiences for the curious, young and old. Get a taste of everything Egypt’s ecology has to offer and start planning your environmentally conscious, once-in-a-lifetime trip now! 6-13 With one of the best 25 beaches in WADI the world, turquoise tranquility meets ancient heritage at Wadi El EL GEMAL Gemal National Park. Abu Galum is a divers’ and snorkelers’ 1 14-21 ultimate paradise, but also provides ABU beachside camping, various watersports, hiking, and stargazing; every kind of explorer will find something to love GALUM about Abu Galum. 2 22-29 History, wildlife, and underwater exploration NABQ – Nabq has it all! 3 30-37 One of the most serene RAS spots on Egypt’s Red Sea, Ras Muhammad brims MUHAMMAD with coral reefs! 4 38-45 Discover rich Bedouin heritage, ST- a strong legacy in ecotourism, and some of Egypt’s highest KATHERINE mountaintops. -

Key Development Challenges Facing Egypt Situation Analysis

SITUATION ANALYSIS: KEY DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES FACING EGYPT 2010 Lead Author Professor Heba Handoussa, Coordinator, Situation Analysis Taskforce This Situation Analysis is a multi-stakeholder document prepared by a Taskforce, led by Heba Handoussa, which consulted with sector-specific experts, independent advisors to government, UN Agencies and other national and international development partners in Egypt. The Taskforce also reviewed a wide array of official documents and recent development literature on Egypt. The Taskforce has gratefully received and accommodated as much as possible numerous comments on the various drafts of the report. ii CONTENTS Preface Fayza Aboulnaga, Minister of International Cooperation V Foreword James Rawley, Chair of the Development Partners Group VII Preamble Heba Handoussa, Coordinator Situation Analysis Taskforce IX Acknowlegments XI Acronyms XIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XV INTRODUCTION AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 1 1. Purpose of Situation Analysis and Guiding Principles 1 2. Participation and Consultation Process 2 3. Strategic Issues Facing Aid Effectiveness in Egypt 2 4. Conceptual Framework for the Situation Analysis and the Three Pillars of Sustainable Development 4 5. Progress on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 6 6. Role and Participation for the Different Stakeholders in the Implementation of the SA 9 7. GOE Strategic Objectives and Five Year Planning 11 PART ONE: KEY CHALLENGES IDENTIFIED IN THE SITUATION ANALYSIS 15 PART TWO: SITUATION ANALYSIS 25 I. PILLAR ONE: SUSTAINABLE AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH 25 I.1 Macro Policy and Stability 25 I.2 Competitiveness 28 1.3 Growth Engines 29 I.3.a Manufacturing: Industrial, International Trade and Internal Market Policies 29 I.3.b Agriculture 31 I.3.c Tourism 32 I.3.d Information and Communications Technology (ICT) 33 I.3.e Renewable Energy 35 I.3.f Construction and Housing 36 I.3.g Micro and Small Enterprises (MSE) 36 I.4 Employment Strategy for Youth 41 II. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Spatial patterns of population dynamics in Egypt, 1947-1970 El-Aal, Wassim A.E. -H. M. Abd How to cite: El-Aal, Wassim A.E. -H. M. Abd (1977) Spatial patterns of population dynamics in Egypt, 1947-1970, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7971/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk SPATIAL PATTERNS OF POPULATION DYNAMICS , IN EGYPT, 1947-1970 VOLUME I by Wassim A.E.-H. M. Abd El-Aal, B.A., M.A. (Graduate Society) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Social Sciences for the degree of Doctor of PhDlosophy Uru-vorsity of Dm n?n' A.TDI 1077 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged Professor J.