The Practice of Distributed Leadership by Management and Its Limitations in Two Spanish Secondary Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Comparative Research on Iot-Based Supply Chain Risk Management

International Comparative Research on IoT-based Supply Chain Risk Management A/Prof. Yu Cui Graduate School of Business Administration and Economics, Otemon Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan Email: [email protected] Prof. Hiroki Idota Faculty of Economics, Kindai University Prof. Masaharu Ota Graduate School of Business, Osaka City University International Comparative Research on IoT-based Supply Chain Risk Management ABSTRACT In this paper, we firstly discuss current status and problems of food supply chain, which has been attached more importance in supply chain studies in recent years. And then, a review and analysis of the research on traceability systems for IoT-based food supply chains will be conducted. In the latter part, we introduce and explain the establishment of food supply chains in Thailand and China and their respective traceability systems with case studies. Moreover, we conduct a systematic analysis regarding the changes and effects the blockchain made on supply chains. Furthermore, through a case analysis of Japan, explicit speculation and forecast would be made on how blockchain affects the development of traceability systems of IoT- based food supply chain. Keywords: Food Supply Chain, Risk Management, IoT-based Traceability System, Blockchain INTRODUCTION In 2011, Thailand suffered a severe flooding which occurs once in 50 years. Its traditional industrial base - Ayutthaya Industrial Park was flooded and nearly 200 factories were closed down. In the same year, Japan’s 311 Kanto Earthquake also caused serious losses to the manufacturing industry and numerous supply chain companies in Japan. And recently, scandals involving data falsification in automotive, steel and carbon fiber have caused great impact on a large number of related supply chain companies and they are faced with the dilemma of supply chain disruption. -

![Master of Education in Educational Leadership and Management [Oupm016]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5058/master-of-education-in-educational-leadership-and-management-oupm016-155058.webp)

Master of Education in Educational Leadership and Management [Oupm016]

Open University of Mauritius Master of Education in Educational Leadership and Management [OUpm016] 1. Rationale and Objectives of the Programme The Master of Education in Educational Leadership and Management at the Open University of Mauritius is a programme intended for anyone with a strong interest in educational leadership and management. People need to master the 21st Century leadership skills to ensure sustainable leadership in their educational institutions and to lead their organisation effectively. Indeed, the changing demands of the changing school characteristics require that those involved in it be well prepared to manage the learners, educators, parents and even work towards community outreach. Else, modern leaders, be they educator leaders, school leaders, community leaders or group leaders may destroy the functioning of the organisation. This programme further develops the leadership skills of people who are engaged in the management of institutions at the micro, macro and meso levels. The educators, the school heads, the superintendents, the directors of institutions, the administrators among all those involved in educational institutions are agents of change towards school effectiveness and improvement. It aims to assist graduates of different disciplines to pursue a career in education, with a leadership and management focus. All those who are in management positions but without relevant qualifications in educational leadership and management and who aspire to occupy such positions are provided with the vast knowledge in the field to expand their knowledge and bring into their learning their professional experience to have a deeper understanding into the practices of leadership and management. More specifically, the programme aims at: Improving understanding of leadership practices in social, cultural, political and policy contexts Utilising existing and emerging international research-informed knowledge of educational leadership and management 1 Enabling a deeper understanding of the learner’s organisation and the educational environment. -

Distributed Leadership Practice: the Subject Matters1

Distributed Leadership Practice: The Subject Matters1 Jennifer Z. Sherer Northwestern University Preliminary draft prepared for the symposium Recent Research in Distributed Leadership at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA, April 15, 2004. Please do not distribute. 1 Work on this paper was supported by the Distributed Leadership Project which is funded by research grants from the National Science Foundation (REC-9873583) and the Spencer Foundation. Northwestern University's School of Education and Social Policy and Institute for Policy Research also supported work on this paper. All opinions and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of any funding agency. Please send all correspondence to the author at Northwestern University, School of Education and Social Policy, 2115 North Campus Drive, Evanston, IL 60201 or to [email protected]. Case study chapter jz 4/28/04 Page 1 of 52 Introduction The distributed leadership perspective suggests that one way to examine leadership practice is to focus on how the situation of practice shapes the activity of instructional leadership. In schools, the situation of instruction is shaped in part by the subject-matter organization of the curriculum (Stodolsky, 1988; McLaughlin and Talbert, 1993). This paper investigates how this subject-matter organization of instruction constitutes a key aspect of the situation of school leadership practice. Elementary school leaders often talk about their leadership in general terms, but I claim that there are differences between subject matter leadership practice. My argument centers on the question of how leadership practice in literacy is similar to and/or different from leadership practice in mathematics. -

Design Issues in Distributed Management Information Systems

DESIGN ISSUES IN DISTRIBUTED MANAGEMENT INFORMATION SYSTEMS by JACOB AKOKA B.S., Faculte des Sciences-Paris (1970) S.M., University of Paris VI (1971) Doctorat 3eme Cycle, University of Paris VI (1975) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE .OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 4, 1978 Signature of Author .................................................. Sloan School of Management, May 4, 1978 Certified by ......................................................... Thesis Supervisor Accepted by ......................................................... Chairman, Department Committee DESIGN ISSUES IN DISTRIBUTED MANAGEMENT INFORMATION SYSTEMS by Jacob Akoka Submitted to the Department of Management on May 4, 1978 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ABSTRACT Due to the advances in computer network technology and the steadily decreasing cost of hardware, distributed information systems have become a potential alternative to centralized information systems.' This thesis analyzes issues related to the design of distributed information systems. Most of the research done in the past can be characterized by a piece- meal approach since it tends to consider the computer network design issue and the distributed data base design issue separately. The critical survey presented in Chapter 2 points out the need to integrate both issues in an overall design approach. In an attempt to incorporate most of the factors that compose distributed information systems, we present a global model in which network topology, communication channels capacity, size of computer hardware, pricing schemes, and routing dis- ciplines are interrelated in an optimal design. In addition, we show how to derive from the global model a design model for distributed database systems. -

Self-Management for Large-Scale Distributed Systems

Self-Management for Large-Scale Distributed Systems AHMAD AL-SHISHTAWY PhD Thesis Stockholm, Sweden 2012 TRITA-ICT/ECS AVH 12:04 KTH School of Information and ISSN 1653-6363 Communication Technology ISRN KTH/ICT/ECS/AVH-12/04-SE SE-164 40 Kista ISBN 978-91-7501-437-1 SWEDEN Akademisk avhandling som med tillstånd av Kungl Tekniska högskolan framlägges till offentlig granskning för avläggande av teknologie doktorsexamen i elektronik och datorsystem onsdagen den 26 september 2012 klockan 14.00 i sal E i Forum IT-Universitetet, Kungl Tekniska högskolan, Isajordsgatan 39, Kista. Swedish Institute of Computer Science SICS Dissertation Series 57 ISRN SICS-D–57–SE ISSN 1101-1335. © Ahmad Al-Shishtawy, September 2012 Tryck: Universitetsservice US AB iii Abstract Autonomic computing aims at making computing systems self-managing by using autonomic managers in order to reduce obstacles caused by manage- ment complexity. This thesis presents results of research on self-management for large-scale distributed systems. This research was motivated by the in- creasing complexity of computing systems and their management. In the first part, we present our platform, called Niche, for program- ming self-managing component-based distributed applications. In our work on Niche, we have faced and addressed the following four challenges in achiev- ing self-management in a dynamic environment characterized by volatile re- sources and high churn: resource discovery, robust and efficient sensing and actuation, management bottleneck, and scale. We present results of our re- search on addressing the above challenges. Niche implements the autonomic computing architecture, proposed by IBM, in a fully decentralized way. -

Enterprise Architecture Techniques for SAP Customers

October 2007 Enterprise Architecture Techniques for SAP Customers by Derek Prior Enterprise architecture has rapidly matured in recent years as a business-driven technique to provide companies with the big picture needed to optimize long-term IT investments. Some of the leading SAP customers have been quietly deploying enterprise architecture techniques to transform their business and prepare for SOA. Why haven’t you? Enterprise Strategies Report Acronyms and Initialisms ADM Architecture development method ERP Enterprise resource planning BPM Business process management ISV Independent software vendor CMDB Configuration management database ITIL IT infrastructure library CRM Customer relationship management PPM Project portfolio management DMTF Distributed Management Task Force SOA Service-oriented architecture EA Enterprise architecture TOGAF The Open Group Architecture Framework EAF Enterprise architecture framework © Copyright 2007 by AMR Research, Inc. AMR Research® is a registered trademark of AMR Research, Inc. No portion of this report may be reproduced in whole or in part without the prior written permission of AMR Research. Any written materials are protected by United States copyright laws and international treaty provisions. AMR Research offers no specific guarantee regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information presented, but the professional staff of AMR Research makes every reasonable effort to present the most reliable information available to it and to meet or exceed any applicable industry standards. AMR Research is not a registered investment advisor, and it is not the intent of this document to recommend specific companies for investment, acquisition, or other financial considerations. This is printed on 100% post-consumer recycled fiber. It is manufactured entirely with wind-generated electricity and in accordance with a Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) pilot program that certifies products made with high percentages of post-consumer reclaimed materials. -

Distributed Management System for Infocommunication Networks Based on TM Forum Framework

Distributed management system for infocommunication networks based on TM Forum Framework Valery P. Mochalov Natalya Yu. Bratchenko Sergey V. Yakovlev [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Darya V. Gosteva [email protected] Department of Infocommunications, North-Caucasus University, Stavropol, Russian Federation Abstract The existing management systems for networks and communication ser- vices do not guarantee in full an efficient rendering of next-generation infocommunication services. The Open Digital Architecture (ODA) is expected to simplify dramatically and automate main business pro- cesses. A key principle of the ODA is using the component approach with the logic of microservices and Open APIs. The concept of Frame- worx gives an exact description for the components of business pro- cesses in terms of their functions, associated information and other characteristics. The performance of a distributed operational manage- ment system depends on the quality of solving several tasks as follows: the distribution of program components among processor modules; the prioritization of business processes with parallel execution; the elim- ination of dead states and interlocks during execution; the reduction of system cost to integrate separate components of business processes. The deadlocks of parallel business processes are eliminated using an interpretation of the classical file sharing example with two processes and also the methodology of colored Petri nets, with implementation in CPN Tools. This paper develops a model of a distributed operational management system for next-generation communication networks that assesses the efficiency of operational activities for a communication company. 1 Introduction Due to high competition in the field of telecommunications, network convergence processes and the need for new business models, it is important to develop methods of operational cost reduction and risk decrease in digital business management. -

Strength Found Through Distributed Leadership by Theodore J

Strength Found Through Distributed Leadership By Theodore J. Peters, Principal; Richard Carr, Instructional Supervisor; and Jaime Doldan, Supervisor of Curriculum and Instruction, Township of Franklin School District The Changing Demands legislation has focused both on advanc- lenges. In 2010, the district had to cre- ing America’s international competitive- ate and implement improvement action of School Leaders ness and closing the achievement gap plans in an effort to increase student Today’s principals and supervisors among students, making “accountability performance on state standardized are faced with increasing demands, the centerpiece of the education agen- assessments. Initial efforts included prompting their responsibilities to da” (Linn, Baker, & Betebenner, 2002, the implementation of common plan- evolve dramatically over the past few p. 3) in the United States. The need for ning time and professional learning decades. In addition to holding the schools to meet academic performance communities (PLCs), understanding largely managerial roles of the past, requirements has further solidified the that teachers needed opportunities to modern school leaders are expected need for principals and supervisors to work, plan, and learn together. How- to facilitate efficient operations, pro- embrace collective efforts to meet such ever, there was a disconnect, as many vide the instructional guidance to help high demands. of the meetings were administratively teachers develop professionally, and The Township of Franklin Public driven, and genuine collaborative maintain the primary importance of School District has faced similar mod- efforts focused on student learning furthering student learning. Ongoing ern educational demands and chal- were lacking. The district realized that Educational Viewpoints -32- Spring 2018 it needed to empower its teachers Putting Distributed by developing methods of increased Leadership in Action The culture necessary leadership opportunities. -

ESSS Outline Distributed Leadership in Early Years and Childcare

ESSS Outline Distributed leadership in early years and childcare Dr Lauren Smith 19 December, 2017 Introduction This Outline seeks to address the following question relating to approaches to self directed support: How is leadership relevant to people working at different levels in childcare organisations? It explores examples of frameworks of leadership at all levels, and identifies examples of leadership at all levels specifically within a childcare context. The purpose of this enquiry was to feed into the development of induction and professional development resources for an early learning and childcare organisation in Scotland, to help employees within the organisation to develop an understanding of how leadership is relevant and applicable to their roles and to participate in service development and provision. Final resources may be shared in the future by the organisation to support workforce development across the sector. The information need for this enquiry was understood as being within the area of distributed leadership/leadership at all levels/situational approaches to leadership within the fields of education/early years/childcare. The aim of this Outline is to provide information about what leadership qualities may be relevant to early years and childcare practitioners, identify examples of what these may look like in practice, and highlight training and development resources that may support practitioners. This information and evidence is intended to be restructured by the original enquirer within their own conceptual framework that best suits their own contextual needs. About the evidence presented below Although we identified some evidence around distributed leadership in relevant fields, leadership research in early childhood education and care “is a relatively new undertaking” (Hujala et al. -

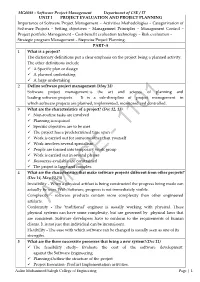

Software Project Management

MG6088 - Software Project Management Department of CSE / IT UNIT I PROJECT EVALUATION AND PROJECT PLANNING Importance of Software Project Management – Activities Methodologies – Categorization of Software Projects – Setting objectives – Management Principles – Management Control – Project portfolio Management – Cost-benefit evaluation technology – Risk evaluation – Strategic program Management – Stepwise Project Planning. PART-A 1 What is a project? The dictionary definitions put a clear emphasis on the project being a planned activity. The other definitions include A Specific plan or design A planned undertaking A large undertaking 2 Define software project management.(May 14) Software project management is the art and science of planning and leading software projects. It is a sub-discipline of project management in which software projects are planned, implemented, monitored and controlled. 3 What are the characteristics of a project? (Dec 12, 13) Non-routine tasks are involved Planning is required Specific objectives are to be met The project has a predetermined time span Work is carried out for someone other than yourself Work involves several specialism People are formed into temporary work group Work is carried out in several phases Resources available are constrained The project is large and complex. 4 What are the characteristics that make software projects different from other projects? (Dec 14, May 12,15) Invisibility - When a physical artifact is being constructed the progress being made can actually be seen. With Software, progress is not immediately visible. Complexity - software products contain more complexity than other engineered artifacts. Conformity - The ‘traditional’ engineer is usually working with physical. These physical systems can have some complexity, but are governed by physical laws that are consistent. -

Distributed Coordination of Mobile Agent Teams: the Advantage of Planning Ahead

Distributed Coordination of Mobile Agent Teams: The Advantage of Planning Ahead Laura Barbulescu, Zachary B. Rubinstein, Stephen F. Smith, and Terry L. Zimmerman The Robotics Institute Carnegie Mellon University 5000 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh PA 15024 {laurabar,zbr,sfs,wizim}@cs.cmu.edu ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION We consider the problem of coordinating a team of agents In many practical domains, a team of agents is faced with engaged in executing a set of inter-dependent, geographically the problem of carrying out geographically dispersed tasks dispersed tasks in an oversubscribed and uncertain environ- under evolving execution circumstances in a manner that ment. In such domains, where there are sequence-dependent maximizes global payoff. Consider the situation following setup activities (e.g., travel), we argue that there is inher- a natural disaster such as an earthquake or hurricane in a ent leverage to having agents maintain advance schedules. remote region. A recovery team is charged with surveying In the distributed problem solving setting we consider, each various sites, rescuing injured, determining what damage agent begins with a task itinerary, and, as execution un- there is to the infrastructure (power, gas, water) and effect- folds and dynamics ensue (e.g., tasks fail, new tasks are dis- ing repairs. The tasks that must be performed entail various covered, etc.), agents must coordinate to extend and revise dependencies; some rescues cannot be safely completed un- their plans accordingly. The team objective is to maximize til infrastructure is stabilized, certain repairs require parts the utility accrued from executed actions over a given time that must be brought on site or prerequisite repairs to other horizon. -

Distributed Leadership in Organizations a Review of Theory

International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 13, 251–269 (2011) DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00306.x Distributed Leadership in Organizations: A Review of Theory and Researchijmr_306 251..269 Richard Bolden Centre for Leadership Studies, University of Exeter Business School, Rennes Drive, Exeter EX4 4ST, UK Corresponding author email: [email protected] The aim of this paper is to review conceptual and empirical literature on the concept of distributed leadership (DL) in order to identify its origins, key arguments and areas for further work. Consideration is given to the similarities and differences between DL and related concepts, including ‘shared’, ‘collective’, ‘collaborative’, ‘emergent’, ‘co-’ and ‘democratic’ leadership. Findings indicate that, while there are some common theo- retical bases, the relative usage of these concepts varies over time, between countries and between sectors. In particular, DL is a notion that has seen a rapid growth in interest since the year 2000, but research remains largely restricted to the field of school education and of proportionally more interest to UK than US-based academics. Several scholars are increasingly going to great lengths to indicate that, in order to be ‘distrib- uted’, leadership need not necessarily be widely ‘shared’ or ‘democratic’ and, in order to be effective, there is a need to balance different ‘hybrid configurations’ of practice. The paper highlights a number of areas for further attention, including three factors relating to the context of much work on DL (power and influence; organizational boundaries and context; and ethics and diversity), and three methodological and developmental challenges (ontology; research methods; and leadership development, reward and recognition).