Film Directors by Deborah Hunn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

John Waters (Writer/Director)

John Waters (Writer/Director) Born in Baltimore, MD in 1946, John Waters was drawn to movies at an early age, particularly exploitation movies with lurid ad campaigns. He subscribed to Variety at the age of twelve, absorbing the magazine's factual information and its lexicon of insider lingo. This early education would prove useful as the future director began his career giving puppet shows for children's birthday parties. As a teen-ager, Waters began making 8-mm underground movies influenced by the likes of Jean-Luc Godard, Walt Disney, Andy Warhol, Russ Meyer, Ingmar Bergman, and Herschell Gordon Lewis. Using Baltimore, which he fondly dubbed the "Hairdo Capitol of the World," as the setting for all his films, Waters assembled a cast of ensemble players, mostly native Baltimoreans and friends of long standing: Divine, David Lochary, Mary Vivian Pearce, Mink Stole and Edith Massey. Waters also established lasting relationships with key production people, such as production designer Vincent Peranio, costume designer Van Smith, and casting director Pat Moran, helping to give his films that trademark Waters "look." Waters made his first film, an 8-mm short, Hag in a Black Leather Jacket in 1964, starring Mary Vivian Pearce. Waters followed with Roman Candles in 1966, the first of his films to star Divine and Mink Stole. In 1967, he made his first 16-mm film with Eat Your Makeup, the story of a deranged governess and her lover who kidnap fashion models and force them to model themselves to death. Mondo Trasho, Waters' first feature length film, was completed in 1969 despite the fact that the production ground to a halt when the director and two actors were arrested for "participating in a misdemeanor, to wit: indecent exposure." In 1970, Waters completed what he described as his first "celluloid atrocity," Multiple Maniacs. -

'I'm SO FUCKING BEAUTIFUL I CAN't STAND IT MYSELF': Female Trouble, Glamorous Abjection, and Divine's Transgressive Pe

CUJAH MENU ‘I’M SO FUCKING BEAUTIFUL I CAN’T STAND IT MYSELF’: Female Trouble, Glamorous Abjection, and Divine’s Transgressive Performance Paisley V. Sim Emerging from the economically depressed and culturally barren suburbs of Baltimore, Maryland in the early 1960s, director John Waters realizes flms that bridge a fascination with high and low culture – delving into the putrid realities of trash. Beginning with short experimental flms Hag in a Black Leather Jacket (1964), Roman Candles (1966), and Eat Your Makeup (1968), the early flms of John Waters showcase the licentious, violent, debased and erotic imagination of a small community of self-identifed degenerates – the Dreamlanders. Working with a nominal budget and resources, Waters wrote, directed and produced flms to expose the fetid underbelly of abject American identities. His style came into full force in the early 1970s with his ‘Trash Trio’: Multiple Maniacs (1970), Pink Flamingos (1972), and Female Trouble (1974). At the heart of Waters’ cinematic achievements was his creation, muse, and star: Divine.1 Divine was “’created’ in the late sixties – by the King of Sleaze John Waters and Ugly-Expert [makeup artist] Van Smith – as the epitome of excess and vulgari- ty”2. Early performances presented audiences with a “vividly intricate web of shame, defance, abjection, trauma, glamour, and divinity that is responsible for the profoundly moving quality of Divine as a persona.”3 This persona and the garish aesthetic cultivated by Van Smith aforded Waters an ideal performative vehicle to explore a world of trash. Despite being met with a mix of critical condemnation and aversion which relegated these flms to the extreme periph- ery of the art world, this trio of flms laid the foundation for the cinematic body of work Waters went on to fesh out in the coming four decades. -

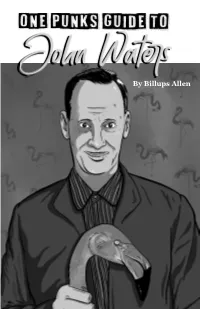

By Billups Allen Billups Allen Spent His Formative Years in and Around the Washington D.C

By Billups Allen Billups Allen spent his formative years in and around the Washington D.C. punk scene. He graduated from the University of Arizona with a creative writing major and a film minor. He has worked in seven different record stores around the country and currently lives in Memphis, Tennessee where he works for Goner Records, publishes Cramhole zine, contributes music and movie writing regularly to Razorcake, Ugly Things, and Lunchmeat magazines, and writes fiction. (cramholezine.com, [email protected]) Illustrations by Codey Richards, an illustrator, motion designer, and painter. He graduated from the University of Alabama in 2009 with a BFA in Graphic Design and Printmaking. His career began by creating album art and posters for local Birmingham venues and bands. His appreciation of classic analog printing and advertising can be found as a common theme in his work. He currently works and resides at his home studio in Birmingham, Alabama. (@codeyrichardsart, codeyrichards.com) Layout by Todd Taylor, co-founder and Executive Director of Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. This zine is made possible in part by support by the Los Angeles County Department of Arts and Culture. Printing Courtesy of Razorcake Press razorcake.org ne rainy weekday, my friend and I went to a small Baltimore shop specializing in mid-century antiques called Hampden Junque. -

Figuring Jewishness in George Cukor's a Double Life

article Figuring Jewishness in George Cukor’s A Double Life Elyce rae Helford AbstrAct This study considers the ways in which Jewishness figures in the production of the 1947 film A Double Life, contextualized within Hollywood director George Cukor’s personal experience, film oeuvre, and the post–world war ii era in which it was released. issues of cultural assimilation and discourses of gender, race, class, and ethnicity are evident in film form, content, and especially process, including casting, direction, narrative, and visual design. From the film’s mobilization of blackface to its condemnation of “ethnic” femininity, this little-studied, oscar-nominated thriller about a murderous shakespearean actor offers valuable commentary on Jewish identity and anxieties in mid-twentieth-century America. In The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929–1968, Andrew Sarris states, “It is no accident that many of [George] Cukor’s characters are thespians of one form or another.”1 Such insight is echoed and extended by multiple biographers, from Gavin Lambert (1972) and Gene D. Phillips (1982) to Patrick McGilligan (1991) and Emanuel Levy (1994), who find theater and theatricality central to the director’s films as well as his life. Before moving to Hollywood, the young Cukor was a hopeful actor, a stage manager, and a director in New York. Upon arrival in California, his first position was as speech coach to actors entering the new realm of talking pictures. And in films throughout his career, theatrical performance plays a significant role. Cukor is well known for his screen 114 | Jewish Film & New Media, Vol. 1, No. -

Loc66-Line-Up-2013.Pdf

Line-up Locarno, 17 July 2013 Via Ciseri 23, ch–6601 Locarno t +41(0)91 21 21 | f +41(0)91 21 49 [email protected] | www.pardo.ch The press kit and stills can be downloaded from our website www.pardo.ch/press (Press Area) Excerpts of some of the offi cial selection’s fi lms are available in broadcast and web quality. In order to download them, please contact the Press Offi ce ([email protected] / +41 91 756 21 21). Join the conversation: #Locarno66 www.Facebook.com/FilmFestivalLocarno www.Twitter.com/FilmFestLocarno Contents 1 Introduction by Carlo Chatrian, Artistic Director 2 Introduction by Mario Timbal, COO 3 Offi cial Juries 4 The 2013 Selection Piazza Grande Concorso internazionale Concorso Cineasti del presente Pardi di domani Fuori concorso Premi speciali Histoire(s) du cinéma Retrospettiva George Cukor Open Doors 5 Industry Days 6 Locarno Summer Academy 7 Swiss Cinema in Locarno 8 Attachments Locarno 66 – Carlo Chatrian – Frontier cinema As I set out to write this short introduction, I naturally looked back over the route covered so far. Before the fi lms themselves, the guests, the programs thought out and implemented over the past months, there fi rst came to mind the people whose substantial contributions have ensured that the Festival fi nds itself where it is today. First and foremost Mark Peranson, Head of Programming, and Nadia Dresti, our International Head, and then Lorenzo Esposito, Sergio Fant and Aurélie Godet (“my” selection committee), Alessandro Marcionni (Pardi di domani), Carmen Werner and Olmo Giovannini (Programming Offi ce), Martina Malacrida and Ananda Scepka (Open Doors). -

On the 20Th Annual Chicago Underground Film Festival

Free One+One Filmmakers Journal Issue 12: Trash, Exploitation and Cult Volume 2 Contents Where volume one focused on Exploitation cinema and the appropriation of its tropes in commercial and art cinema, this volume changes tact, exploring themes of film exhibition and the Carnivalesque. 04 39 The first two articles are dedicated to the former theme. In these articles James Riley White Walls and Empty Rooms: From Cult to Cabaret: and Amelia Ishmael explore the exhibition of underground cinema. From the film festi- A Short History of the Fleapit An Interview with Mink Stole val to the ad hoc DIY screening, these articles adventure into the sometimes forebod- James Riley Bradley Tuck and Melanie Mulholland ing landscape of film screenings. The following articles explore the topic of the carni- valesque, both as an expression of working class culture and queer excess. Frances Hatherley opens up this theme with an article on the TV show Shameless exploring the 12 Tyrell48 & Back demonisation of the working classes in Britain and mode of politicisation and defiance The Chicago Underground Film Festival Amelia Ishmael Susan Tyrell Obituary embedded in the TV show itself. Through Frances’ article, we discover in Shameless, Melanie Mulhullond not the somber working class of Mike Leigh or Ken Loach, but the trailer trash of John Waters. Appropriately, therefore, this articles is swiftly followed by a discussion between 24 James Marcus Tucker and Juliet Jacques on Rosa von Praunheim’s City of Lost Souls; Defensive Pleasures: Gerontophila51 a film that wallows in the carnivalesque decadence of queer life. City of Lost Souls is a Class, Carnivalesque and Shameless Bruce LaBruce film that springs from a tradition of queer cinema with obvious parallels with the works Frances Hatherley of Paul Morrissey, Jack Smith, George and Mike Kuchar and John Waters. -

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Videocassette Collection: Additional Series

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Videocassette Collection: Additional Series Mark Micallef’s donation Box 1 of 2 – 12 video tapes No Show Title Channel Date Time 1 Donahue (US) Gay Cops 10 21/07/1994 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 1 Ricki Lake (US) We’re married but one of is gay 10 20/07/1995 12.00 pm - 1.00 pm 1 Donahue (US) When one spouse is gay and a marriage unravels, 10 10/08/1995 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 2 Donahue (US) Gays beware – this town wants you out 10 6/04/1992 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 2 Oprah Winfrey Show (US) Fired because you are gay 10 6/04/1992 2.30 pm - 3.30 pm Woman wins eight year battle to care for disabled 2 Donahue (US) lesbian lover 10 5/05/1992 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 3 Donahue (US) Transvestite shopping spree 10 27/08/1991 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 3 Donahue (US) Transsexual family – leather biker turns lacy mom 10 28/01/1991 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 3 Donahue (US) Boy scouts v girls, atheists and homosexuals 10 29/08/1991 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 4 Donahue (US) Lesbian baby boom 10 11/11/1991 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 4 Donahue (US) Female impersonators 10 6/01/1992 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm The most gorgeous transexual ever - Tula with ex- 4 Donahue (US) fiance and her mum 10 21/01/1992 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 5 Donahue (US) My husband-to-be is a transexual and mum’s upset 10 13/04/1992 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 5 Oprah Winfrey Show (US) Wife confronts husband’s gay lover 10 13/04/1992 2.30 pm - 3.30 pm Desperate for a job, he cross-dressed to feed his 5 Donahue (US) family 10 14/04/1992 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 6 Donahue (US) Transvestite hookers 10 31/07/1991 1.30 pm - 2.30 pm 6 Donahue (US) -

John Waters on Making Multiple Maniacs

presents The theatrical premiere of John Waters’ rarely seen trash classic! “ Can only be compared to Todd Browning’s Freaks.” —Los Angeles Free Press “ The pope of trash.” —William S. Burroughs “ Even the garbage is too good a place for it.” —Mary Avara, Maryland Board of Censors John Waters’ gloriously grotesque, unavailable-for-decades second feature comes to theaters at long last, replete with all Multiple Maniacs was shot on an Auricon 16 mm camera using manner of depravity, from robbery to murder to one of cinema’s Kodak black-and-white reversal film with audio magnetic stripe. most memorably blasphemous moments. Made on a shoestring Additional exterior footage was filmed on a Bell & Howell hand- budget in Baltimore, with Waters taking on nearly every technical cranked camera. Plus-X film was used for the exteriors, while task, this gleeful mockery of the peace-and-love ethos of its era Tri-X was used for the interiors. The reversal original was kept features the Cavalcade of Perversion, a traveling show put on by in John Waters’ closet from 1970 until he moved in 1990, after a troupe of misfits whose shocking proclivities are topped only which it was kept in Waters’ attic at occasional 100-plus-degree by those of their leader: the glammer-than-glam, larger-than- temperatures—until the Criterion Collection retrieved it and life Divine, who’s out for blood after discovering her lover’s scanned it in 4K resolution on a Lasergraphics Director film affair. Starring Waters’ beloved regular cast the Dreamlanders scanner at Metropolis Post in New York. -

December 6, 2011 (XXIII:15) George Cukor, MY FAIR LADY (1964, 170 Min.)

December 6, 2011 (XXIII:15) George Cukor, MY FAIR LADY (1964, 170 min.) Directed by George Cukor Book of musical play by Alan Jay Lerner From a play by George Bernard Shaw Screenplay by Alan Jay Lerner Produced by Jack L. Warner; James C. Katz (1994 restoration) Original Music by André Previn Cinematography by Harry Stradling Sr. Film Editing by William H. Ziegler Production Design by Cecil Beaton and Gene Allen Art Direction by Gene Allen and Cecil Beaton Costume Design by Cecil Beaton and Michael Neuwirth Musical play lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner Music by Frederick Loewe Choreography by Hermes Pan Audrey Hepburn...Eliza Doolittle Rex Harrison...Professor Henry Higgins Stanley Holloway...Alfred P. Doolittle Report, 1960 Let's Make Love, 1960 Heller in Pink Tights, 1957 Wilfrid Hyde-White...Colonel Hugh Pickering Wild Is the Wind, 1957 Les Girls, 1956 Lust for Life, 1956 Gladys Cooper...Mrs. Higgins Bhowani Junction, 1954 A Star Is Born, 1954 It Should Happen Jeremy Brett...Freddy Eynsford-Hill to You, 1953 The Actress, 1952 Pat and Mike, 1952 The Theodore Bikel...Zoltan Karpathy Marrying Kind, 1950 Born Yesterday, 1950 A Life of Her Own, Mona Washbourne...Mrs. Pearce 1949 Adam's Rib, 1949 Edward, My Son, 1947 A Double Life, Isobel Elsom...Mrs. Eynsford-Hill 1944 Gaslight, 1942 Keeper of the Flame, 1940 The John Holland...Butler Philadelphia Story, 1939 The Women, 1936 Camille, 1936 Romeo and Juliet, 1935 Sylvia Scarlett, 1935 David Copperfield, 1965 Academy Awards: 1933 Little Women, 1933 Dinner at Eight, 1932 Rockabye, 1932 Best Picture – Jack L. Warner A Bill of Divorcement, 1932 What Price Hollywood?, 1931 Best Director – George Cukor Tarnished Lady, 1930 The Royal Family of Broadway, 1930 The Best Actor in a Leading Role – Rex Harrison Virtuous Sin, and 1930 Grumpy. -

Dancing Lady Robert Z. Leonard M-G-M USA 1933 16Mm 5/6/1972

Listed Screening Season Title Director Studio Country Year Format runtime Date Notes Dancing Lady Robert Z. Leonard M-G-M USA 1933 16mm 5/6/1972 The first screening ever! 11/25/1972 Per Trib article from 11/23/1972, "our meeting this Saturday will be our last until after the Holidays" Go Into Your Dance Archie Mayo Warner Bros. USA 1935 16mm 1/18/1975 per Chuck Schaden's Nostalgia Newsletter 1/1975 Sunny Side Up David Butler Fox Film Corp. USA 1929 16mm 1/25/1975 per Chuck Schaden's Nostalgia Newsletter 1/1975 Shall We Dance Mark Sandrich RKO USA 1937 16mm 2/1/1975 per Chuck Schaden's Nostalgia Newsletter 1/1975 You'll Never Get Rich Sidney Lanfield Columbia USA 1941 16mm 2/8/1975 per Chuck Schaden's Nostalgia Newsletter 2/1975 - subbed in for A Night at the Opera Stand-In Tay Garnett United Artists USA 1937 16mm 2/15/1975 per Chuck Schaden's Nostalgia Newsletter 2/1975 - subbed in for No Man Of Her Own Now And Forever Henry Hathaway Paramount USA 1934 16mm 2/22/1975 per Chuck Schaden's Nostalgia Newsletter 2/1975 Spy Smasher Returns William Witney Republic USA 1942 16mm 3/1/1975 per Chuck Schaden's Nostalgia Newsletter 3/1975 - subbed in for Sing You Sinners White Woman Stuart Walker Paramount USA 1933 16mm 3/8/1975 per Chuck Schaden's Nostalgia Newsletter 1/1975 Broadway Gondolier Lloyd Bacon Warner Bros. USA 1935 16mm 3/15/1975 per Chuck Schaden's Nostalgia Newsletter 4/1975 Argentine Nights Albert S.