The Roaring Twenties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elisabeth Epstein: Moscow–Munich–Paris–Geneva, Waystations of a Painter and Mediator of the French-German Cultural Transfer

chapter 12 Elisabeth Epstein: Moscow–Munich–Paris–Geneva, Waystations of a Painter and Mediator of the French-German Cultural Transfer Hildegard Reinhardt Abstract The artist Elisabeth Epstein is usually mentioned as a participant in the first Blaue Reiter exhibition in 1911 and the Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon in 1913. Living in Munich after 1898, Epstein studied with Anton Ažbe, Wassily Kandinsky, and Alexei Jawlensky and participated in Werefkin’s salon. She had already begun exhibiting her work in Paris in 1906 and, after her move there in 1908, she became the main facilitator of the artistic exchange between the Blue Rider artists and Sonia and Robert Delaunay. In the 1920s and 1930s she was active both in Geneva and Paris. This essay discusses the life and work of this Russian-Swiss painter who has remained a peripheral figure despite her crucial role as a mediator of the French-German cultural transfer. Moscow and Munich (1895–1908) The special attraction that Munich and Paris exerted at the beginning of the twentieth century on female Russian painters such as Alexandra Exter, Sonia Delaunay, Natalia Goncharova, and Olga Meerson likewise characterizes the biography of the artist Elisabeth Epstein née Hefter, the daughter of a doc- tor, born in Zhytomir/Ukraine on February 27, 1879. After the family’s move to Moscow, she began her studies, which continued from 1895 to 1897, with the then highly esteemed impressionist figure painter Leonid Pasternak.1 Hefter’s marriage, in April 1898, to the Russian doctor Miezyslaw (Max) Epstein, who had a practice in Munich, and the birth of her only child, Alex- ander, in March 1899, are the most significant personal events of her ten-year period in Bavaria’s capital. -

The Abuse of Architectonics by Decorating in an Era After Deconstructivism

THE ABUSE OF ARCHITECTONICS BY DECORATING IN AN ERA AFTER DECONSTRUCTIVISM DECONSTRUCTION OF THE TECTONIC STRUCTURE AS A WAY OF DECORATION PIM GERRITSEN | 1186272 MSC3 | INTERIORS, BUILDINGS, CITIES | STUDIO BACK TO SCHOOL AR0830 ARCHITECTURE THEORY | ARCHITECTURAL THINKING | GRADUATION THESIS FALL SEMESTER 2008-2009 | MARCH 09 THESIS | ARCHITECTURAL THINKING | AR0830 | PIM GERRITSEN | 1186272 | MAR-09 | P. 1 ‘In fact, all architecture proceeds from structure, and the first condition at which it should aim is to make the outward form accord with that structure.’ 1 Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1872) Lectures Everything depends upon how one sets it to work… little by little we modify the terrain of our work and thereby produce new configurations… it is essential, systematic, and theoretical. And this in no way minimizes the necessity and relative importance of certain breaks of appearance and definition of new structures…’ 2 Jacques Derrida (1972) Positions ‘It is ironic that the work of Coop Himmelblau, and of other deconstructive architects, often turns out to demand far more structural ingenuity than works developed with a ‘rational’ approach to structure.’ 3 Adrian Forty (2000) Words and Buildings Theme In recent work of architects known as deconstructivists the tectonic structure of the buildings seems to be ‘deconstructed’ in order to decorate the building’s image. In other words: nowadays deconstruction has become a style with the architectonic structure used as decoration. Is the show of architectonic elements in recent work of -

Press Release Frank Gehry First Major European

1st August 2014 PRESS RELEASE communications and partnerships department 75191 Paris cedex 04 FRANK GEHRY director Benoît Parayre telephone FIRST MAJOR EUROPEAN 00 33 (0)1 44 78 12 87 e-mail [email protected] RETROSPECTIVE press officer 8 OCTOBER 2014 - 26 JANUARY 2015 Anne-Marie Pereira telephone GALERIE SUD, LEVEL 1 00 33 (0)1 44 78 40 69 e-mail [email protected] www.centrepompidou.fr For the first time in Europe, the Centre Pompidou is to present a comprehensive retrospective of the work of Frank Gehry, one of the great figures of contemporary architecture. Known all over the world for his buildings, many of which have attained iconic status, Frank Gehry has revolutionised architecture’s aesthetics, its social and cultural role, and its relationship to the city. It was in Los Angeles, in the early 1960s, that Gehry opened his own office as an architect. There he engaged with the California art scene, becoming friends with artists such as Ed Ruscha, Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg, Larry Bell, and Ron Davis. His encounter with the works of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns would open the way to a transformation of his practice as an architect, for which his own, now world-famous, house at Santa Monica would serve as a manifesto. Frank Gehry’s work has since then been based on the interrogation of architecture’s means of expression, a process that has brought with it new methods of design and a new approach to materials, with for example the use of such “poor” materials as cardboard, sheet steel and industrial wire mesh. -

Photograms1999 Pressrelease

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE PHOTOGRAM: 1918–1948 January 23 – March 6, 1999 Ubu Gallery is pleased to present The Photogram: 1918–1948, a survey of the historical development of a unique and beautiful photographic process – an abstract marriage of light and chemistry made without the objectifying presence of the camera. The exhibition will open on January 23, 1999 and run through March 6, 1999. At its simplest, a photogram is essentially a one-of-a-kind negative image created by placing objects on a sheet of photographic paper that is exposed to light and then developed and processed in the manner of a normal photographic print. Although variants of this type of process date back to the origins of photography, the creative potential of the photogram went unrealized until unlocked by Christian Schad, a member of the original Zurich Dada group, in 1918. At the heart of the Dadaist aesthetic was the concept of creating a new art from the detritus of a “morally corrupt,” bourgeois society. Like the materials found in Kurt Schwitters’s collages, Schad appropriated as his subject matter an eclectic array of found objects – discarded tickets, fabric, newsprint, string, etc. Tristan Tzara dubbed Schad’s series of small format photograms “Schadographs,” playing upon the name of their creator and the shadow aspect of the process. In the early 1920s, Man Ray, Lázló Moholy-Nagy and El Lissitzky – working independently – pushed the medium past Schad’s collage-like photograms. Their most significant innovation was the introduction of a sense of depth or interior space obtained by varying the dimensionality, volume and translucence of the objects and the form and manner of the lighting sources. -

New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933 on View: October 4, 2015–January 18, 2016 Location: BCAM, 2Nd Floor

Exhibition: New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933 On View: October 4, 2015–January 18, 2016 Location: BCAM, 2nd Floor Image captions on page 5 (Los Angeles—April 7, 2015) The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933, the first comprehensive show in the United States to explore the themes that characterize the dominant artistic trends of the Weimar Republic. Organized in association with the Museo Correr in Venice, Italy, this exhibition features nearly 200 paintings, photographs, drawings, and prints by more than 50 artists, many of whom are little known in the United States. Key figures—Otto Dix, George Grosz, Christian Schad, August Sander, and Max Beckmann— whose heterogeneous careers are essential to understanding 20th century German modernism, are presented together with lesser known artists, including Herbert Ploberger, Hans Finsler, Georg Schrimpf, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, Carl Grossberg, and Aenne Biermann, among others. Special attention is devoted to the juxtaposition of painting and photography, offering the rare opportunity to examine both the similarities and differences between the movement’s diverse media. During the 14 years of the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), artists in Germany grappled with the devastating aftermath of World War I: the social, cultural, and economic effects of rapid modernization and urbanization; staggering unemployment and despair; shifting gender identities; and developments in technology and industry. Situated between the end of World War I and the Nazi assumption of power, Germany’s first democracy thrived as a laboratory for widespread cultural achievement, witnessing the end of Expressionism, the exuberant anti- art activities of the Dadaists, the establishment of the Bauhaus design school, and the emergence of a new realism. -

Art 142: the History of Photography Unit 8: Mass Media and Marketing Mass Media and Marketing

Art 142: The History of Photography Unit 8: Mass Media and Marketing Mass Media and Marketing The end of WWI propelled a period of experimentalism in photography that shattered the Victorian conventions and generated a new, modern covenant with the social world. Mass Media and Marketing Dada and After ● “Dada, a nonsensical sounding word chosen by a group of writers, artists and poets ● Identifies a new emerging art movement able to express despair brought on by WWI and break conventions and intellectual barriers ● Christian Schad, German artist associated with Zurich Dada group made, “Schadographs”. ● May have been referencing both “Shadowgraphs or the german word, “Schaden” which means damaged evoking the Dada sense of things falling apart. Christian Schad, Schadograph 24b, c. 1920. Gelatin silver print. Mass Media and Marketing Dada and After ● Berlin Dada group more political than Zurich group and wanted to make social statements. ● Adopted photomontage as a key medium, a “paste picture” or Klebebild finished as a photograph Hannah Höch, Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands (Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany), 1919. Photomontage. Nationalgalerie Staatliche Museen, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin. Mass Media and Marketing Dada and After ● Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann were two of the earliest dadaists to make photomontages ● Höch engaged the theme of New Woman, images juxtaposed traditional roles of women with symbols of modernity ● Hausmann, one of the few communists that insisted on women’s equality in any new society. Hannah Höch, Denkmal I: Aus einem ethnographischen Museum (Monument 1: From an Ethnographic Museum), 1924. -

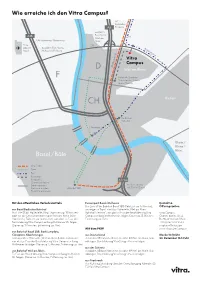

Anfahrt DE.Pdf

Wie erreiche ich den Vitra Campus? A5 Karlsruhe / A5 Freiburg Ausfahrt / Exit / Sortie A35 B3 Weil am A35 Strassburg / Strasbourg Rhein Euro E35 Airport Ausfahrt / Exit / Sortie Rö Basel Mulhouse / Freiburg me rstras se Vitra Campus Müllheimer Str. Bahnhof / Zentrum Train station / Centre Gare / Centre Badischer Bahnhof Claraplatz 55 Rhein / Rhine / Rhin Basel / Bâle Zug / Train Tram Bus Fussweg / Footpath / A2/A3 Chemin pédestre 8 2 Landesgrenze / A2 Bern / Berne National border / Bahnhof SBB A3 Zürich / Zurich Frontière nationale Mit den öffentlichen Verkehrsmitteln Euroairport Basel/Mulhouse Kontakt & Bus Linie 50 bis Bahnhof Basel SBB (Fahrtzeit ca. 15 Minuten), Öffnungszeiten von Basel Badischer Bahnhof umsteigen in Tram Linie 8 bis Haltestelle „Weil am Rhein Bus Linie 55 bis Haltestelle „Vitra“ (Fahrtzeit ca. 15 Minuten) Bahnhof/Zentrum“, von dort zu Fuss der Beschilderung Vitra Vitra Campus oder mit der Deutschen Bahn nach Weil am Rhein (eine Campus entlang Müllheimer Str. folgen (Dauer ca. 15 Minuten, Charles-Eames-Str. 2 Haltestelle, Fahrzeit ca. 5 Minuten), von dort zu Fuss der Entfernung ca. 1 km) D-79576 Weil am Rhein Beschilderung Vitra Campus entlang Müllheimer Str. folgen +49 (0)7621 702 3500 (Dauer ca. 15 Minuten, Entfernung ca. 1 km) [email protected] Mit dem PKW www.vitra.com/campus von Bahnhof Basel SBB, Barfüsserplatz, Claraplatz, Kleinhüningen aus Deutschland Mo-So 10-18 Uhr Tram Linie 8 bis Haltestelle „Weil am Rhein Bahnhof/Zentrum“, Autobahn A5 Karlsruhe-Basel, Ausfahrt 69 Weil am Rhein, links 24. Dezember 10-14 Uhr von dort zu Fuss der Beschilderung Vitra Campus entlang abbiegen, Beschilderung Vitra Design Museum folgen Müllheimer Str. -

Frank Gehry Biography

G A G O S I A N Frank Gehry Biography Born in 1929 in Toronto, Canada. Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. Education: 1954 B.A., University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA. 1956 M.A., Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Select Solo Exhibitions: 2021 Spinning Tales. Gagosian, Beverly Hills, CA. 2016 Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy. Building in Paris. Espace Louis Vuitton Venezia, Venice, Italy. 2015 Architect Frank Gehry: “I Have an Idea.” 21_21 Design Sight, Tokyo, Japan. 2015 Frank Gehry. LACMA, Los Angeles, CA. 2014 Frank Gehry. Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. Voyage of Creation. Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, France. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Athens, Greece. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, China. 2013 Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Davies Street, London, England. Frank Gehry At Work. Leslie Feely Fine Art. New York, NY. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Paris Project Space, Paris, France. Frank Gehry at Gemini: New Sculpture & Prints, with a Survey of Past Projects. Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl, New York, NY. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA. 2011 Frank Gehry: Outside The Box. Artistree, Hong Kong, China. 2010 Frank O. Gehry since 1997. Vitra Design Museum, Rhein, Germany. Frank Gehry: Eleven New Prints. Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl, New York, NY. 2008 Frank Gehry: Process Models and Drawings. Leslie Feely Fine Art, New York, NY. 2006 Frank Gehry: Art + Architecture. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada. 2003 Frank Gehry, Architect: Designs for Museums. Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, MN. Traveled to Corcoran Art Gallery, Washington, D.C. 2001 Frank Gehry, Architect. -

박물관의 비정형 건축형태와 중심공간과의 상관성에 관한 연구 a Study on Correlation Between Atypical Architecture Classification and Main Public Space of the Museums

https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2021.21.03.088 박물관의 비정형 건축형태와 중심공간과의 상관성에 관한 연구 A Study on Correlation between Atypical Architecture Classification and Main Public Space of the Museums 박상준 신라대학교 실내건축디자인전공 Sang-Jun Park([email protected]) 요약 본 연구는 박물관 건축의 작품 중 특별 전시의 기능을 제외한 상설전시가 주를 이루는 박물관을 중심으로 하였다. 사례연구를 통해 나타난 정형, 비정형, 세그먼트, 사선형의 형태를 기준으로 하여, 164건의 작품사례 에 적용한 결과 건축형태를 비정형, 정형, 반정형, 세그먼트, 사선형, 선형으로 재분류 하고, 박물관 건축 형태 와 중심 공간과의 상관성의 유무를 유추함으로써 비정형 건축형태와 중심공간과의 관계가 성립하는가를 도출 하고자 다음과 같이 내용을 정리하였다. 전체적으로 대부분 비정형박물관건축형태와 일치하는 중심공간의 비 정형 형태로서 92.7% 분포도를 나타났다. 결과적으로 전반적으로 박물관 비정형 건축형태가 다수 나타났으며 정형보다는 비정형 건축형태에 있어서 중심공간과의 상관성이 성립되는 것으로서 향후 박물관 건축형태는 비 정형이 지속적으로 발전 할 것으로 추정되고 중심 공간 실내건축 설계는 건축형태와의 상관성을 고려하여 설 계를 지향하는 기초적 근거자료로서 제시하고자 한다. ■ 중심어 :∣박물관∣비정형∣건축형태∣상관성∣중심 공간∣ Abstract This study focused on the museums mainly holding permanent exhibitions except for the function of special exhibition in museum architectural works. This study aimed to draw the possibility to establish the relation between architectural form and central space of museums, by applying the forms like formal form, informal form, segment form, and diagonal form shown through a case study to total 164 work cases, reclassifying the architectural form into informal form, formal form, semi-formal form, segment form, diagonal form, and linear form, and then analogizing the matter of correlation between architectural form and central space of museums. -

Deconstructivism: Richness Or Chaos to Postmodern Architecture Olivier Clement Gatwaza1, Xin CAO1

Deconstructivism: Richness or Chaos to Postmodern Architecture Olivier Clement Gatwaza1, Xin CAO1 1School of Landscape Architecture, Beijing Forestry University, 35 Qinghua East Road Beijing, 100083 China Abstract: In this paper, we examine the involvement of deconstructivism in the evolvement of postmodern architecture and ascertain its public acceptance dimensions as it progressively conquers postmodern architecture. To achieve this, we used internet search engines such as Google, Yahoo, Wikipedia and Web of Science, we also used knowledge repositories such as Google Scholar and the world’s largest travel site TripAdvisor to gather information and data about origin, evolution, characteristics and relationship between postmodernism and deconstructivism. We’ve based our judgment on concepts from famous architects, political leaders and public opinion to access the suitability of architectural style. The result of this research shows that postmodernism architecture buildings have an average 96.8% of visitor’s satisfaction ranking; while deconstructivism architecture buildings when taken alone, a decrease of 2% in visitor’s satisfaction ranking is perceived. In addition, strong comments against the upcoming architectural style confirm that deconstructivism still has ingredients to endorse in order to impose its trajectory towards the top of modern architecture. Being a piece of a globalized world, deconstructivism architecture in the most of the cases tends to disregard the history and culture of its location which compromise its innovative, -

Night Fever Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today 17 March – 9 September 2018

Vitra Design Museum Charles-Eames-Straße 2 79576 Weil am Rhein/Basel Germany www.design-museum.de PRESS CONFERENCE 15 March 2018, 2 pm OPENING 16 MARCH 2018, 6 pm Opening Talk with Ben Kelly, Peter Saville, and Konstantin Grcic PRESS DOWNLOADS www.design-museum.de/press_images Night Fever Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today 17 March – 9 September 2018 The nightclub is one of the most important design spaces in contemporary culture. Since the 1960s, nightclubs have been epicentres of pop culture, distinct spaces of nocturnal leisure providing architects and designers all over the world with opportunities and inspiration. »Night Fever. Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today« offers the first large-scale examination of the relationship between club culture and design, from past to present. The exhibition presents nightclubs as spaces that merge architecture and interior design with sound, light, fashion, graphics, and visual effects to create a modern Gesamtkunstwerk. Examples range from Italian clubs of the 1960s created by the protagonists of Radical Design to the legendary Studio 54 where Andy Warhol was a regular, from the Haçienda in Manchester designed by Ben Kelly to more recent concepts by the OMA architecture studio for the Ministry of Sound in London. The exhibits on display range from films and vintage photographs to posters, flyers, and fashion, but also include contemporary works by photographers and artists such as Mark Leckey, Chen Wei, and Musa N. Nxumalo. A spatial installation with music and light effects takes visitors on a fascinating journey through a world of glamour and subcultures – always in search of the night that never ends. -

Edwin Chan Architect

Edwin Chan Architect Professional Experience Edwin Chan received his Bachelor of Arts from the College of Environmental Design at UC Berkeley, and Master of Architecture from the Graduate School of Design at Harvard. After graduation, Edwin joined Frank O. Gehry & Associates in Los Angeles; and has collaborated with Mr. Gehry as Design Partner on many of the firm’s most significant cultural and institutional projects. Edwin has lectured both in the US and internationally, and has served as visiting professor of architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and was appointed the Howard Friedman Visiting Professor of Architectural Practice at UC Berkeley for Fall semester of 2012. Edwin has been recognized with many awards and distinctions. Most recently, Edwin received the honor of “Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres” from the Republic of France, and the Graham Foundation Grant for Advanced Studies for the Arts in 2013. In January 2012, Edwin launched his independent practice EC3. Based in Los Angeles, EC3 embraces a vision for professional practice that transcends culture and geography; and is committed to Empower Cross-disciplinary Collaboration in Creativity. By using physical models extensively to explore options in spatial organizations as well as aesthetic throughout all phases of the project, EC3 promotes highly inter-active and collaborative dialogues with clients consulting team, as well as policy makers and stakeholders. EC3 is supported by a team of professionals with more than 20 years of experience in projects from a variety of scales, from cultural, mixed-use, institutional, urban planning to furniture, as well as exhibition and set designs.