Fund Forward.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brookfield Infrastructure Partners LP (BIP.N)2 16 June 2017

16 June 2017 Americas/Canada Equity Research Infrastructure Brookfield Infrastructure Partners LP (BIP.N) Rating (from NEUTRAL) OUTPERFORM Price (14-Jun-17, US$) 39.43 UPGRADE RATING Target price (US$) (from 40.00) 44.00 52-week price range (US$) 40.91 - 27.91 Market cap (US$ m) 9,606.72 A Tactical Trade; Upgrade to Outperform on Target price is for 12 months. Index Inclusion Potential and Organic Re-Rate Research Analysts Andrew M. Kuske ■ A Timing Trade: We upgrade Brookfield Infrastructure Partners, LP (BIP) to 416 352 4561 [email protected] Outperform from the previous Neutral and increase our target price to US$44 Paul Tan from the prior US$40 in light of some tactical issues. In addition, we believe a 416 352 4593 solid fundamental organic growth story is underappreciated which is poised [email protected] to deliver value. Simply, the near-term issues revolve around two factors: (a) potential index inclusion; and, (b) NTS economics. We do not believe the full extent of these issues is appreciated by the market (albeit index potential may be creeping in). Longer-term, we continue to believe the fundamental organic growth story is not appreciated versus BIP's historical M&A bias. ■ Index inclusion: With the S&P/TSX undergoing a consultation process for selected index criteria, the potential inclusion of BIP in the Composite is likely to have a meaningful impact on unit demand around the Q3 index revision. At that time, BIP would look to join the other Brookfield siblings (namely Brookfield Renewable and Brookfield Properties) in the Composite as a top 40 float weighted name which creates a tactical trade. -

PB 20-02 -- Leasing the Turnpike.Pub

Commonwealth Vol. 20, No. 02 POLICY BRIEF May 2008 Leasing the Pennsylvania Turnpike Frequently Asked Questions & Answers COMMONWEALTH FOUNDATION & REASON FOUNDATION 1. Does Pennsylvania need more money for its roads, highways, bridges and mass transit systems? The Pennsylvania Transportation Funding and Reform Commission (November 2006 report) identified the need for an increase of $1.7 billion in annual funding simply to maintain the state’s current transportation infrastructure. The bi-partisan commission recommended an increase of: $965 million for roads, highways, and bridges. $760 million for mass transit. 2. Didn’t Act 44 of 2007—which will impose new tolls on the currently free Interstate-80—solve our transportation funding problem? Act 44 provides less than half the funding needed for roads, highways, and bridges, according to the Penn- sylvania Transportation Funding and Reform Commission report. $450 million for roads, highways, and bridges in FY 2007-08. $300 million for mass transit in FY 2007-08. Act 44 provides an average of only $946 million over the next 10 years and does not reach $1.7 billion un- til 2036. Furthermore, Act 44 funding increases are also unlikely to keep pace with inflation and are depend- ent on federal approval for tolling I-80, which has not been granted by the Federal Highway Administration. 3. What if the Federal Highway Administration rejects Pennsylvania’s application to toll I-80? Act 44 will generate only $450 million annually if the Federal Highway Administration does not approve the tolling of I-80. $200 million for roads, highways, and bridges—only one-fifth the identified need of $965 million. -

2019 Consolidated Management Report 2

ABERTIS INFRAESTRUCTURAS, S.A. AND SUBSIDIARIES CONSOLIDATED MANAGEMENT REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019 2019 CONSOLIDATED MANAGEMENT REPORT 2 Contents 1. Letter to the Shareholders and Stakeholders ............................................................................................................ 3 2. Summary of the year's performance ....................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Abertis in 2019 ............................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2. 2019 Milestones............................................................................................................................................. 6 3. Strategy .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 3.1 Business model .............................................................................................................................................. 8 3.2 Strategic approach ......................................................................................................................................... 10 4. Corporate Governance .......................................................................................................................................... 12 4.1 Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................... -

Comision Nacional Del Mercado De Valores (Cnmv)

Relevant Fact Investor Relations Inst. Investors & Research Tel. +34 91 595 10 00 Shareholder’s Office Tel. +34 902 30 10 15 [email protected] COMISION NACIONAL DEL MERCADO DE VALORES (CNMV) In compliance with article 228 of the Consolidated Text of the Spanish Securities Market Law, ABERTIS INFRAESTRUCTURAS, S.A. ("Abertis" or the “Company”), hereby notifies the Spanish National Securities Market Commission of the following RELEVANT FACT The company sends the report from the Board of Directors of Abertis Infraestructuras, S.A. in relation to the Tender Offer made by Hochtief AG. Madrid, 17 April 2018 abertis.com / [email protected] REPORT BY THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS OF ABERTIS INFRAESTRUCTURAS, S.A. ON THE TAKEOVER BID BY HOCHTIEF AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT AUTHORISED BY THE NATIONAL SECURITIES MARKET COMMISSION (CNMV) ON 12 APRIL 2018 The present report has been drawn up by the Board of Directors of Abertis Infraestructuras, S.A. (hereinafter “Abertis” or the “Company”) in relation to the voluntary takeover bid made by Hochtief Aktiengesellschaft (hereinafter, “Hochtief” or the “Bidder”), on 18 October 2017, to acquire all of the shares that make up the share capital of Abertis, as amended on 23 March 2018 (hereinafter the bid and its amendment are referred to as the “Takeover Bid” or the “Bid”). The present report has been approved by the Abertis Board of Directors at its meeting of 16 April 2018, in compliance with the provisions of article 134.4 of the Redrafted Text of the Securities Market Law, approved by Royal Legislative Decree No. 4/2015, of 23 October (hereinafter the “LMV”, for its Spanish initials), and article 24 of Royal Decree No. -

What States Should Know When Considering Public-Private Partnerships to Fund Transportation

Driven by Dollars What States Should Know When Considering Public-Private Partnerships to Fund Transportation MARCH 2009 The Pew Charitable Trusts applies the power of knowledge to solve today’s most challenging problems. Our Pew Center on the States identifies and advances effective policy approaches to critical issues facing states. PEW CENTER ON THE STATES Susan Urahn, managing director Research Team Design and Publications Team Michele Mariani Vaughn Carla Uriona Lori Grange Alyson Freedman Melissa Maynard Communications Team Kil Huh Andrew McDonald Jane Breakell Janet Lane Ann Cloke Jessica Riordan Research Consultants G. Edward DeSeve, Chairman, Strategy and Solution Partners Timothy James, Professor, W.P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State University Donald F. Kettl, Robert A. Fox Leadership Professor, University of Pennsylvania Katherine Barrett and Richard Greene, Barrett and Greene, Inc. Will Wilson ACKNOWLEDGMENTS LEARN MORE The following three experts served as external reviewers for this report. While these experts have screened the report for accuracy, For more information from the Pew Center on neither they nor their organizations necessarily endorse its findings the States about economic competitiveness or conclusions. We thank them for their assistance. and government efficiency and effectiveness, please see: Jennifer L. Dorn, President and Chief Executive Officer, National Academy of Public Administration • Grading the States 2008, assessing all 50 states on how well they manage their infrastructure Mortimer Downey, -

Grupo ACS Key Operating & Financial Figures

Works on the construction of Lima’s Metro Line 2 (Peru) WorldReginfo - 71a985cf-f25d-4c84-8bee-c421f0c02885 RESULTS REPORT 1Q19 INDEX 1 Executive Summary 3 Main figures 3 Relevant facts 5 2 Consolidated Financial Statements 6 2.1 Income Statement 6 2.1.1 Sales and Backlog 7 2.1.2 Operating Results 9 2.1.3 Financial Results 9 2.1.4 Results from Associates 10 2.1.5 Net Profit Attributable to the Parent Company 10 2.2 Consolidated Balance Sheet 11 2.2.1 Non-Current Assets 12 2.2.2 Working Capital 12 2.2.3 Net Worth 12 2.2.4 Net Debt 12 2.3 Net Cash Flows 13 2.3.1 Operating Activities 13 2.3.2 Investments 14 2.3.3 Other Cash Flows 14 3 Evolution per Areas of Activity 15 3.1 Infrastructures 15 3.1.1. Construction 15 3.1.2 Abertis 17 3.2 Industrial Services 18 3.3 Services 20 4 Annex 21 4.1 Main figures per area of activity 21 4.2 Share data 22 4.3 Exchange Rate Effect 23 4.4 Main Awards 24 4.4.1 Infrastructure 24 4.4.2 Industrial Services 24 4.4.3 Services 24 5 ACS Group organizational structure 25 6 Glossary 26 2 WorldReginfo - 71a985cf-f25d-4c84-8bee-c421f0c02885 RESULTS REPORT 1Q19 1 Executive Summary Main figures Grupo ACS Key operating & financial figures Euro Million 3M18 3M19 Var. Turnover 8,671 9,263 +6.8% Backlog 66,677 75,399 +13.1% Months 22 23 EBITDA (1) 686 761 +10.9% Margin 7.9% 8.2% EBIT (1) 482 501 +3.9% Margin 5.6% 5.4% Attributable Net Profit 249 282 +12.9% EPS 0.80 € 0.91 € +14.3% Net Investments 161 544 n.s Investments 183 571 Disposals 21 27 Total Net (Debt)/Cash (359) (897) +149.8% Businesses' Net (Debt)/Cash (158) (778) Project Financing (201) (119) Data presented according to ACS Group management criteria. -

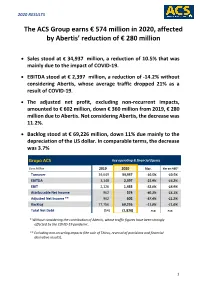

The ACS Group Earns € 574 Million in 2020, Affected by Abertis' Reduction

2020 RESULTS The ACS Group earns € 574 million in 2020, affected by Abertis’ reduction of € 280 million Sales stood at € 34,937 million, a reduction of 10.5% that was mainly due to the impact of COVID-19. EBITDA stood at € 2,397 million, a reduction of -14.2% without considering Abertis, whose average traffic dropped 21% as a result of COVID-19. The adjusted net profit, excluding non-recurrent impacts, amounted to € 602 million, down € 360 million from 2019, € 280 million due to Abertis. Not considering Abertis, the decrease was 11.2%. Backlog stood at € 69,226 million, down 11% due mainly to the depreciation of the US dollar. In comparable terms, the decrease was 3.7% Grupo ACS Key operating & financial figures Euro Million 2019 2020 Var. Var ex-ABE* Turnover 39,049 34,937 -10.5% -10.5% EBITDA 3,148 2,397 -23.9% -14.2% EBIT 2,126 1,433 -32.6% -18.9% Attributable Net Income 962 574 -40.3% -15.1% Adjusted Net Income ** 962 602 -37.4% -11.2% Backlog 77,756 69,226 -11.0% -11.0% Total Net Debt (54) (1,820) n.a. n.a. * Without considering the contribution of Abertis, whose traffic figures have been strongly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. ** Excluding non-recurring impacts (the sale of Thiess, reversal of provisions and financial derivative results). 1 2020 RESULTS 1. Consolidated Results The Group’s 2020 ordinary net profit accounted for € 602 million, € 360 million less than the previous year. This decline is mainly due to the evolution of Abertis, whose traffic was heavily affected by the lockdown measures related to COVID- 19, reducing its contribution by € 280 million. -

M.8894 - Atlantia / Acs Hochtief / Abertis Infraestructuras

Disclaimer : The Competition DG makes the information provided by the notifying parties in section 1.2 of Form CO available to the public in order to increase transparency. This information has been prepared by the notifying parties under their sole responsibility, and its content in no way prejudges the view the Commission may take of the planned operation. Nor can the Commission be held responsible for any incorrect or misleading information contained therein. M.8894 - ATLANTIA / ACS HOCHTIEF / ABERTIS INFRAESTRUCTURAS SECTION 1.2 Description of the concentration The Commission received notification of the proposed concentration whereby Atlantia S.p.A. (Italy) and ACS Group (Spain) / HOCHTIEF (Germany) will acquire joint control over Abertis Infraestructuras S.A. (Spain) within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) and Article 3(4) of Council Regulation (EC) 139/2004. The acquisition of control is carried out by way of a series of transactions, by way of acquisition of shares, regulated by an investment agreement that will ultimately lead Abertis to have the following shareholding structure: (i) Atlantia will own 50% plus one share; (ii) ACS will own 30%; and (iii) HOCHTIEF will own 20% minus one share. More particularly, Atlantia S.p.A. is an Italian holding company active in the following five areas of business: “Italian motorways”, via Autostrade per l’Italia S.p.A.; “Overseas motorways”, with presence in Chile and Brazil and minor assets in Poland and India; “Italian airports”, with the two Rome airports managed by Aeroporti di Roma S.p.A.; “Overseas airports”, namely the three airports on the Côte d’Azur; and “Other related businesses” which inter alia includes activities carried out by Telepass S.p.A., Autostrade Tech S.p.A., Pavimental S.p.A., and Spea Engineering S.p.A. -

FTSE Goldman Sachs ESG-Enhanced Global Investment-Grade Corporate Bond Index | August 31, 2021

FTSE Russell Factsheet | FTSE Goldman Sachs ESG-Enhanced Global Investment-Grade Corporate Bond Index | August 31, 2021 INDEX CONSTITUENTS September 2021 Index Profile - Index data as of August 31, 2021 Coupon Maturity Index Weight Description (%) (YYYYMMDD) (%) 3M CO 1.750 20230214 0.0031 3M CO 2.250 20230315 0.0041 3M CO 0.950 20230515 0.0044 3M CO 3.250 20240214 0.0052 3M CO 2.000 20250214 0.0048 3M CO 2.650 20250415 0.0033 3M CO 3.000 20250807 0.0036 3M CO 2.250 20260919 0.0096 3M CO 1.500 20261109 0.0059 3M CO 2.875 20271015 0.0129 3M CO 3.625 20280914 0.0167 3M CO 3.375 20290301 0.0220 3M CO 2.375 20290826 0.0255 3M CO 3.050 20300415 0.0161 3M CO 1.750 20300515 0.0132 3M CO 1.500 20310602 0.0130 3M CO 5.700 20370315 0.0195 3M CO 3.125 20460919 0.0033 3M CO 3.625 20471015 0.0036 3M CO 4.000 20480914 0.0089 3M CO 3.250 20490826 0.0068 3M CO 3.700 20500415 0.0048 A2A SPA 0.625 20310715 0.0117 A2A SPA 0.625 20321028 0.0034 ABB FIN BV 0.625 20230503 0.0051 ABB FIN BV 0.750 20240516 0.0055 ABB FIN BV 0.000 20300119 0.0182 ABBOTT IRELAND FINANCING DAC 0.875 20230927 0.0084 ABBOTT IRELAND FINANCING DAC 0.100 20241119 0.0141 ABBOTT IRELAND FINANCING DAC 1.500 20260927 0.0089 ABBOTT IRELAND FINANCING DAC 0.375 20271119 0.0042 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 3.400 20231130 0.0069 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 2.950 20250315 0.0066 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 3.750 20261130 0.0268 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 1.150 20280130 0.0089 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 1.400 20300630 0.0154 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 4.750 20361130 0.0532 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 6.150 20371130 0.0202 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 6.000 -

Brookfield Infrastructure Partners L.P. 2018 ANNUAL REPORT UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington D.C

Brookfield Infrastructure Partners L.P. 2018 ANNUAL REPORT UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F ¨ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018 OR ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ¨ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number 001-33632 BROOKFIELD INFRASTRUCTURE PARTNERS L.P. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Bermuda (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 73 Front Street Hamilton, HM 12, Bermuda (Address of principal executive offices) Jane Sheere 73 Front Street Hamilton, HM 12, Bermuda +1-441-294-3309 (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of class Name of each exchange on which registered Limited Partnership Units New York Stock Exchange; Toronto Stock Exchange Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report: 277,347,890 Limited Partnership Units as of December 31, 2018 Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Abertis Infraestructuras, Sa1

1 ABERTIS INFRAESTRUCTURAS, SA 1. INTRODUCTION Abertis is one of the most important groups worldwide in the industry of managing toll roads. It was set up in 2003 after the merger of two Spanish companies: Acesa and Áurea. Nowadays, 8,500 kilometers of high capacity roads are managed by this public limited corporation. Thanks to its internationalization strategy, Abertis operates in 14 countries, being leader in some of them. This has resulted into geographic risk diversification leading to a stable company capable of getting over different business cycles. Sanef (France) and Arteris (Brazil) are some of the many subsidiaries that compose the Abertis group of companies. In addition, it does not only manage toll roads but it also has entered in the communication satellites industry (TDT) by being one of the main shareholders of Hispasat (57.05%) and Cellnex Telecom (34%). Both, Abertis and Cellnex, are listed in the Spanish Stock Exchange and are part of the IBEX 35 index. Acesa, one of the companies that took part in the merger, was established in 1967 and inaugurated the first Spanish toll motorway in 1969 between Montgat and Mataró. From here on, they began the expansion around Spain by building additional stretches between different regions such as El Vendrell - Zaragoza or La Jonquera - Salou, among others. On March 2002, Acesa made a take over bid in order to break the merger process between Iberpistas and Áurea (Dragados' subsidiary). This strategy aimed to be able to compete at at European level. However, Áurea made a counteroffer starting an offer war which finally lead to the merger of both, Acesa and Áurea. -

Abertis Infraestructuras, Sa and Subsidiaries

ABERTIS INFRAESTRUCTURAS, S.A. AND SUBSIDIARIES CONSOLIDATED MANAGEMENT REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2020 2020 CONSOLIDATED MANAGEMENT REPORT 2 Contents 1. Letter to the shareholders and stakeholders ................................................................................................... 3 2. Summary of the year's global performance .................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Abertis in 2020 ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 2020 milestones ................................................................................................................................... 6 3. Strategy .................................................................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Business model .................................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Strategic approach ............................................................................................................................... 10 4. Corporate governance ................................................................................................................................ 12 4.1 Board of Directors ................................................................................................................................ 12 4.2 Board Committees ..............................................................................................................................