Return to the Motherland: Russian Migrants in Hockey's Changing World System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Men's Ice Hockey Championship. Season 2018

KONTINENTAL HOCKEY LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP – RUSSIAN MEN’S ICE HOCKEY CHAMPIONSHIP SEASON 2018/2019 CALENDAR MOSCOW 2018 Participating teams Conference WEST BOBROV DIVISION TARASOV DIVISION DINAMO RIGA CSKA MOSCOW Republic of Latvia Russian Federation HC DYNAMO MOSCOW DINAMO MINSK Russian Federation Republic of Belarus JOKERIT HELSINKI HC SOCHI SOCHI Republic of Finland Russian Federation SEVERSTAL CHEREPOVETS LOKOMOTIV YAROSLAVL Russian Federation Russian Federation SKA SAINT PETERSBURG SLOVAN BRATISLAVA Russian Federation Slovak Republic SPARTAK MOSCOW VITYAZ MOSCOW REGION Russian Federation Russian Federation Conference EAST KHARLAMOV DIVISION CHERNYSHEV DIVISION AVTOMOBILIST YEKATERINBURG ADMIRAL VLADIVOSTOK Russian Federation Russian Federation AK BARS KAZAN AMUR KHABAROVSK Russian Federation Russian Federation METALLURG MAGNITOGORSK AVANGARD OMSK REGION Russian Federation Russian Federation NEFTEKHIMIK NIZHNEKAMSK BARYS ASTANA Russian Federation Republic of Kazakhstan TORPEDO NIZHNY NOVGOROD KUNLUN RED STAR BEIJING Russian Federation People's Republic of China TRAKTOR CHELYABINSK SALAVAT YULAEV UFA Russian Federation Russian Federation SIBIR NOVOSIBIRSK REGION Russian Federation 2 STAGE 1 (REGULAR SEASON) September 1, 2018, Saturday 1 Ak Bars SKA September 2, 2018, Sunday 2 Avtomobilist Dinamo R 3 Metallurg Mg Slovan 4 Traktor CSKA 5 Lokomotiv Avangard 6 Severstal Sibir 7 HC Dynamo M Salavat Yulaev September 3, 2018, Monday 8 Ak Bars Dinamo Mn 9 Neftekhimik Vityaz 10 Torpedo SKA 11 Spartak Amur 12 HC Sochi Admiral 13 Jokerit Kunlun -

CLEVELAND MONSTERS UPDATE Cleveland Has Picked up Three-Straight Wins After a Month of December That Was Impacted by Columbus’ Constant Callups Due to Injuries

BLUE JACKETS.COM/PRESSBOX @BLUEJACKETSPR CLEVELAND MONSTERS UPDATE Cleveland has picked up three-straight wins after a month of December that was impacted by Columbus’ constant callups due to injuries. The Monsters are 17-15-1 (35 pts.) through 35 games and occupy the seventh spot in the North Division and are 13th in the Eastern Conference, currently sitting seven points out of a playoff spot. The club has a plus-3 goal differential and has allowed 96 goals on the season, with Revised: Mon., June 16, 2014 Revised: Mon., June 16, 2014 2014-15 Columbus Blue Jackets 2014-15 Columbus Blue Jackets Cannon Alternate Logo: Proof #2 Cannon Alternate Logo: Proof #2 its 2.74 GAA ranking eighth in the AHL. Logo Variations: Logo Variations: CLEVELAND (AHL) STATS PROSPECTS OF NOTE Skater GP G A Pts +/- PIM Paul Bittner (LW) 29 4 4 8 2 30 WORLD JUNIORS Gabriel Carlsson (D) 28 1 8 9 6 10 Columbus had four prospects par- Adam Clendening (D) 31 5 20 25 6 34 ticipate, with three earning med- Ryan Collins (D) 11 1 2 3 3 6 als, in the 2020 IIHF World Junior Zac Dalpe (C) 18 7 4 11 3 4 Championship, which was held in Marko Dano (LW) 29 3 10 13 -1 61 Ostrava and Trinec, Czech Republic * Trey Fix-Wolansky (RW) 16 2 5 7 -2 12 from Dec. 26-Jan. 5. C Liam Foudy * Maxime Fortier (RW) 8 0 1 1 -5 4 (1st round, 18th overall, 2018 NHL Nathan Gerbe (LW) 30 8 17 25 -8 22 Draft) had three goals and an as- Markus Hannikainen (LW) 18 4 6 10 -2 4 sist in seven games to aid Canada Jakob Lilja (LW) 18 4 5 9 -1 0 in claiming their second WJC gold Ryan MacInnis (C) 28 3 12 15 8 16 in the last three tournaments. -

2016 NHL DRAFT Buffalo, N.Y

2016 NHL DRAFT Buffalo, N.Y. • First Niagara Center Round 1: Fri., June 24 • 7 p.m. ET • NBC Sports Network Rounds 2-7: Sat., June 25 • 10 a.m. ET • NHL Network The Washington Capitals hold the 26th overall selection in the 2016 NHL Draft, which begins on Friday, June 24 at First Niagara Center in Buffalo, N.Y., and will be televised on NBC Sports Network at 7 p.m. Rounds 2-7 will take place on Saturday and will be televised on NHL Network at 10 a.m. The Capitals currently hold six picks in the seven-round draft. Last year, CAPITALS 2016 DRAFT PICKS the team made four selections, including goaltender Ilya Samsonov with the 22nd overall Round Selection(s) selection. 1 26 4 117 CAPITALS DRAFT NOTES 5 145 (from ANA via TOR) Homegrown – Fourteen players (Karl Alzner, Nicklas Backstrom, Andre Burakovsky, John 5 147 Carlson, Connor Carrick, Stanislav Galiev, Philipp Grubauer, Braden Holtby, Marcus 6 177 Johansson, Evgeny Kuznetsov, Dmitry Orlov, Alex Ovechkin, Chandler Stephenson and Tom 7 207 Wilson) who played for the Capitals in 2015-16 were originally drafted by Washington. Capitals draftees accounted for 60.9% of the team’s goals last season and 63.2% of the team’s FIRST-ROUND DRAFT ORDER assists. 1. Toronto Maple Leafs 2. Winnipeg Jets Pick 26 – This year marks the third time in franchise history the Capitals have held the 26nd 3. Columbus Blue Jackets overall selection in the NHL Draft. Washington selected Evgeny Kuznetsov with the 26th pick 4. Edmonton Oilers in the 2010 NHL Draft and Brian Sutherby with the 26th pick in the 2000 NHL Draft. -

2007 SC Playoff Summaries

PITTSBURGH PENGUINS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 2 0 0 9 Craig Adams, Philippe Boucher, Matt Cooke, Sidney Crosby CAPTAIN, Pascal Dupuis, Mark Eaton, Ruslan Fedotenko, Marc-Andre Fleury, Mathieu Garon, Hal Gill, Eric Godard, Alex Goligoski, Sergei Gonchar, Bill Guerin, Tyler Kennedy, Chris Kunitz, Kris Letang, Evgeni Malkin, Brooks Orpik, Miroslav Satan, Rob Scuderi, Jordan Staal, Petr Sykora, Maxime Talbot, Mike Zigomanis Mario Lemieux CO-OWNER/CHAIRMAN Ray Shero GENERAL MANAGER, Dan Bylsma HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 2009 EASTERN CONFERENCE QUARTER—FINAL 1 BOSTON BRUINS 116 v. 8 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 93 GM PETER CHIARELLI, HC CLAUDE JULIEN v. GM/HC BOB GAINEY BRUINS SWEEP SERIES Thursday, April 16 1900 h et on CBC Saturday, April 18 2000 h et on CBC MONTREAL 2 @ BOSTON 4 MONTREAL 1 @ BOSTON 5 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. BOSTON, Phil Kessel 1 (David Krejci, Chuck Kobasew) 13:11 1. BOSTON, Marc Savard 1 (Steve Montador, Phil Kessel) 9:59 PPG 2. BOSTON, David Krejci 1 (Michael Ryder, Milan Lucic) 14:41 2. BOSTON, Chuck Kobasew 1 (Mark Recchi, Patrice Bergeron) 15:12 3. -

Former Canadian Governor General Ramon Hnatyshyn Dead at Age

ïêàëíéë êéÑàÇëü! CHRIST IS BORN! Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXX HE No.KRAINIAN 52 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, DECEMBER 29, 2002 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine Verkhovna Rada caucuses negotiate FormerT CanadianU Governor General W Ramon Hnatyshyn dead at age 68 compromise and adopt 2003 budget by Christopher Guly Canadian Congress. by Yarema A. Bachynsky Nine pro-presidential caucuses. That day Mr. Hnatyshyn, whose parents were Special to The Ukrainian Weekly saw the paper-thin majority of roughly OTTAWA – In death as in his life, of Ukrainian descent, made Ukrainian- 236 deputies oust now former Governor Ramon John Hnatyshyn gave Canada’s Canadian history on December 14, 1989, KYIV – Capping two weeks of sharp of the National Bank of Ukraine Ukrainian community a national profile when he was named Canada’s 24th gov- and at times violent confrontation in the Volodymyr Stelmakh; replace him with with a distinctly personal touch. ernor general, which made him Queen halls of Parliament, the Opposition Four now former MP and Labor Ukraine Party At his family’s request, the December Elizabeth II’s representative in Canada (Our Ukraine, Yulia Tymoshenko Bloc, leader Serhii Tyhypko; re-allocate all 15 23 funeral service for the country’s for- and the country’s de facto head of state. Socialists and Communists) caucuses on committee chair assignments held by the mer governor general, held at Ottawa’s He was sworn into office on January 29, December 24 agreed to cease blocking Opposition Four to members of the Nine; Anglican cathedral, followed the rites of 1990. -

For Immediate Release June 5, 2021 Matthews, Slavin And

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JUNE 5, 2021 MATTHEWS, SLAVIN AND SPURGEON VOTED LADY BYNG TROPHY FINALISTS NEW YORK (June 5, 2021) – Toronto Maple Leafs center Auston Matthews, Carolina Hurricanes defenseman Jaccob Slavin and Minnesota Wild defenseman Jared Spurgeon are the three finalists for the 2020-21 Lady Byng Memorial Trophy, awarded “to the player adjudged to have exhibited the best type of sportsmanship and gentlemanly conduct combined with a high standard of playing ability,” the National Hockey League announced today. Members of the Professional Hockey Writers Association submitted ballots for the Lady Byng Trophy at the conclusion of the regular season, with the top three vote-getters designated as finalists. The winners of the 2021 NHL Awards presented by Bridgestone will be revealed during the Stanley Cup Semifinals and Stanley Cup Final, with exact dates, format and times to be announced. Following are the finalists for the Lady Byng Trophy, in alphabetical order: Auston Matthews, C, Toronto Maple Leafs Matthews posted a League-leading 41 goals, 12 game-winning goals and 222 shots on goal (41-25—66) to earn his first career Maurice “Rocket” Richard Trophy and help the Maple Leafs claim their first division title since 1999-00. Matthews, who ranked fifth among NHL forwards with 21:33 of time on ice per game and ninth among all skaters with 47 takeaways, received 10 penalty minutes during his 52 appearances – the second- fewest among the League’s top 25 scorers behind only Artemi Panarin (6 PIM in 42 GP w/ NYR). The 23-year- old Scottsdale, Ariz., native – a finalist for the second straight season after placing second in voting in 2019-20 – is vying to become the eighth different player to win the Lady Byng Trophy with Toronto and just the second to do so in the expansion era (since 1967-68), following Alexander Mogilny in 2002-03. -

A Detailed Analysis of Player Performance and Development by Draft Round December 2015

A Detailed Analysis of Player Performance and Development by Draft Round December 2015 @OrgSixAnalytics www.OriginalSixAnalytics.com 1 Contents • Introduction • Context: Data Sample/Draft Years • Player Performance/Development • Relative Draft Pick Value • Drafting Success by Team • Conclusions @OrgSixAnalytics www.OriginalSixAnalytics.com 2 Introduction @OrgSixAnalytics www.OriginalSixAnalytics.com 3 Introduction My background is in management consulting and private equity investing; as such, this document is in a quantitative ‘report’ format similar to what you may see in those industries The objective of this analysis is to investigate ‘typical’ player performance and development trajectory after being drafted in a given round, hoping to answer the following: – If a player is drafted in round X, and is ultimately able to make the NHL, by when should they be expected to be a contributing NHL player? – How well does the typical player perform over the course of his career (on various metrics) after being selected in a given round? Within the first round, how do the top 10 overall picks perform versus those taken 11th-30th? – How much more valuable is a pick in the first round versus the other rounds? All things being equal, what should a pick from each round be worth in a trade? – Which teams were the most effective at drafting in the period sampled? Before getting to the questions above, I start with a quick overview of prior work in the area, the methodology used, the constraints of this analysis, as well as covering some basic context -

Biden Visits SNHU, Hopes to Revive the Breast CANCER AWARENESS MONTH "American Dream"

"Keep it positive" -Timothy Parent Volume XVI, Issue II October 21st 2008 Manchester, NH OCTOBER IS: Biden Visits SNHU, Hopes to Revive the BREAST CANCER AWARENESS MONTH "American Dream" Hampshire, stating, “1,400 Aimee Terravechia New Hampshire residents Staff Writer have lost their houses within the last quarter alone.” Many of these figures resonated After visiting the American Biden, both he and Obama are with New Hampshire resi- Legion Hall, Post 7, in Roches- working to address these con- dents who are beginning to ter earlier in the day, Senator Joe cerns by focusing on the econ- feel the financial pinch more Biden, running mate of Barack omy and job creation. and more. Obama, visited Southern New “Our plan,” Biden said, “is Biden also talked at length Hampshire University’s campus to create over two million new about what he considers to be on Monday, October 13th. The jobs averaging at about $50,000 an “attack” campaign being event attracted community mem- per year.” Biden began discuss- run by Senator McCain. The photo provided by Google bers and students alike, drawing ing the impact that these plans crowd, filled with Obama approximately 900 guests. would have on New Hampshire What's Inside? supporters sporting shirts Senator Joe Biden Pages After short speeches by residents. Nine-thousand of that read: McCan’t began News 1-11 both Dave Hendrie, a field orga- these new jobs, he said, would be “booing” at the mention of Obama, Biden said, “McCain wants Business 12 nizer for the Obama campaign created in the Granite State. -

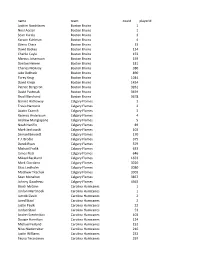

2019 Playoff Draft Player Frequency Report

name team count playerid Joakim Nordstrom Boston Bruins 1 Noel Acciari Boston Bruins 1 Sean Kuraly Boston Bruins 3 Karson Kuhlman Boston Bruins 4 Zdeno Chara Boston Bruins 13 David Backes Boston Bruins 134 Charlie Coyle Boston Bruins 153 Marcus Johansson Boston Bruins 159 Danton Heinen Boston Bruins 181 Charles McAvoy Boston Bruins 380 Jake DeBrusk Boston Bruins 890 Torey Krug Boston Bruins 1044 David Krejci Boston Bruins 1434 Patrice Bergeron Boston Bruins 3261 David Pastrnak Boston Bruins 3459 Brad Marchand Boston Bruins 3678 Garnet Hathaway Calgary Flames 2 Travis Hamonic Calgary Flames 2 Austin Czarnik Calgary Flames 3 Rasmus Andersson Calgary Flames 4 Andrew Mangiapane Calgary Flames 5 Noah Hanifin Calgary Flames 89 Mark Jankowski Calgary Flames 102 Samuel Bennett Calgary Flames 170 T.J. Brodie Calgary Flames 375 Derek Ryan Calgary Flames 379 Michael Frolik Calgary Flames 633 James Neal Calgary Flames 646 Mikael Backlund Calgary Flames 1653 Mark Giordano Calgary Flames 3020 Elias Lindholm Calgary Flames 3080 Matthew Tkachuk Calgary Flames 3303 Sean Monahan Calgary Flames 3857 Johnny Gaudreau Calgary Flames 4363 Brock McGinn Carolina Hurricanes 1 Jordan Martinook Carolina Hurricanes 1 Jaccob Slavin Carolina Hurricanes 2 Jared Staal Carolina Hurricanes 2 Justin Faulk Carolina Hurricanes 22 Jordan Staal Carolina Hurricanes 53 Andrei Svechnikov Carolina Hurricanes 103 Dougie Hamilton Carolina Hurricanes 124 Michael Ferland Carolina Hurricanes 152 Nino Niederreiter Carolina Hurricanes 216 Justin Williams Carolina Hurricanes 232 Teuvo Teravainen Carolina Hurricanes 297 Sebastian Aho Carolina Hurricanes 419 Nikita Zadorov Colorado Avalanche 1 Samuel Girard Colorado Avalanche 1 Matthew Nieto Colorado Avalanche 1 Cale Makar Colorado Avalanche 2 Erik Johnson Colorado Avalanche 2 Tyson Jost Colorado Avalanche 3 Josh Anderson Colorado Avalanche 14 Colin Wilson Colorado Avalanche 14 Matt Calvert Colorado Avalanche 14 Derick Brassard Colorado Avalanche 28 J.T. -

BOSTON BRUINS Vs. TAMPA BAY LIGHTNING

BOSTON BRUINS vs. TAMPA BAY LIGHTNING POST GAME NOTES MILESTONES REACHED: • Charlie Coyle played his 500th NHL game today. • Tampa Bay’s Anthony Cirelli played his 100th NHL game today. WHO’S HOT: • David Krejci had a goal and an assist today, giving him 1-8=9 totals in five of his last six games with 5-13=18 totals in 12 of his last 16 contests ... It was his 20th goal of the season, the fourth 20-goal season of his career, and gives Boston five 20-goal scorers (Pastrnak, Marchand, Bergeron, DeBrusk, Krejci) for the first time since 2013-14. • David Pastrnak had two assists today, giving him 7-8=15 totals in seven of his last nine games with 11-15=26 totals in 14 of his last 17 games played. • Danton Heinen had a goal today, giving him 2-3=5 totals in four of his last nine games. • Matt Grzelcyk had a goal today, giving him 2-2=4 totals in four of his last eight games played. • Charlie McAvoy had an assist today, giving him 1-2=3 totals in three of his last five games. • Steven Kampfer had an assist today, giving him 1-2=3 totals in three of his last five games played. • Tampa Bay’s Braydon Coburn had a goal and an assist today, giving him 1-3=4 totals in two of his last four games. • Tampa Bay’s Anthony Cirelli had a goal and an assist today, giving him 5-4=9 totals in seven of his last 11 games. -

2012 Hockey Conference Program

Putting it on Ice III: Constructing the Hockey Family Abstracts Carly Adams & Hart Cantelon University of Lethbridge Sustaining Community through High Performance Women’s Hockey in Warner, Alberta Canada is becoming increasingly urbanized with small rural communities subject to amalgamation or threatened by decline. Statistics Canada data indicate that by 1931, for the first time in Canadian history, more citizens (54%) lived in urban centre than rural communities. By 2006, this percentage had reached 80%. This demographic shift has serious ramifications for small rural communities struggling to survive. For Warner, a Southern Alberta agricultural- based community of approximately 380 persons, a unique strategy was adopted to imagine a sense of community and to allow its residents the choice to remain ‘in place’ (Epp and Whitson, 2006). Located 65 km south of Lethbridge, the rural village was threatened with the potential closure of the consolidated Kindergarten to Grade 12 school (ages 5-17). In an attempt to save the school and by extension the town, the Warner School and the Horizon School Division devised and implemented the Warner Hockey School program to attract new students to the school and the community. By 2003, the Warner vision of an imagined community (Anderson, 1983) came to include images of high performance female hockey, with its players as visible celebrities at the rink, school, and on main street. The purpose of this paper is to explore the social conditions in rural Alberta that led to and influenced the community of Warner to take action to ensure the survival of their local school and town. -

Washington Capitals Game Notes

Washington Capitals Game Notes Fri, Nov 15, 2019 NHL Game #296 Washington Capitals 14 - 2 - 4 (32 pts) Montréal Canadiens 10 - 5 - 3 (23 pts) Team Game: 21 5 - 1 - 3 (Home) Team Game: 19 6 - 3 - 0 (Home) Home Game: 10 9 - 1 - 1 (Road) Road Game: 10 4 - 2 - 3 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 30 Ilya Samsonov 7 5 1 1 2.45 .915 31 Carey Price 15 9 4 2 2.65 .916 70 Braden Holtby 14 9 1 3 3.06 .903 37 Keith Kinkaid 3 1 1 1 4.36 .879 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 3 D Nick Jensen 20 0 2 2 -5 0 6 D Shea Weber 18 5 9 14 3 12 6 D Michal Kempny 12 3 8 11 10 12 8 D Ben Chiarot 18 3 2 5 4 10 8 L Alex Ovechkin 20 13 10 23 -2 10 11 R Brendan Gallagher 18 8 6 14 5 0 9 D Dmitry Orlov 20 1 7 8 -6 10 13 C Max Domi 18 4 8 12 6 0 13 L Jakub Vrana 20 9 8 17 4 10 14 C Nick Suzuki 18 3 4 7 3 4 14 R Richard Panik 10 0 0 0 0 2 15 C Jesperi Kotkaniemi 12 2 1 3 -1 2 18 C Chandler Stephenson 16 2 1 3 5 4 17 D Brett Kulak 10 0 1 1 -3 4 19 C Nicklas Backstrom 20 4 11 15 -2 2 20 D Cale Fleury 13 0 0 0 -3 2 20 C Lars Eller 20 5 6 11 3 16 21 C Nick Cousins 12 2 5 7 6 2 21 R Garnet Hathaway 20 2 4 6 3 13 24 C Phillip Danault 18 5 6 11 6 4 26 C Nic Dowd 14 2 2 4 3 4 26 D Jeff Petry 18 2 8 10 7 6 28 L Brendan Leipsic 20 2 4 6 2 0 28 D Mike Reilly 8 0 2 2 1 2 33 D Radko Gudas 20 0 5 5 9 21 32 D Christian Folin 5 0 1 1 2 2 34 D Jonas Siegenthaler 20 1 2 3 6 16 40 R Joel Armia 16 6 4 10 5 2 43 R Tom Wilson 20 8 8 16 8 18 41 L Paul Byron 18 1 3 4 3 4 62 L Carl Hagelin 17 0 5 5 1 2 43 C Jordan Weal 10 2 1 3 -4 4 74 D John Carlson 20 8 22 30 15 6 44 C Nate Thompson 18 1 5 6 0 5 77 R T.J.