Elite Bostonian Women's Organizations As Sites of Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

Applying Andragogy to Promote Active Learning in Adult Education In

SHORT PAPER APPLYING ANDRAGOGY TO PROMOTE ACTIVE LEARNING IN ADULT EDUCATION IN RUSSIA Applying Andragogy to Promote Active Learning in Adult Education in Russia https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v6i4.6079 I.V. Pavlova1 and P.A.Sanger2 1 Kazan National Research Technological University, Kazan, Russian Federation 2 Purdue Polytechnic Institute, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA Abstract—In this rapidly changing world of technology and acquire invaluable experience themselves and by observa- economic conditions, it is essential that practicing engineers tion of others in their environment. This experience gives and engineering educators continue to grow in their skills the learner a rich context for applying new knowledge and and knowledge in order to stay competitive and relevant in new techniques. Therefore, as new programs are devel- the industrial and educational work space. This paper de- oped, the student’s professional experience is a valuable scribes the results for a course that combined the best tech- resource and should be incorporated into the curricular niques of andragogy to promote active learning in a curricu- strategy. Active learning using many of the tools from lum of chemistry education, in particular, chemistry labora- andragogy and project based learning could be an attrac- tory education. This experience with two separate corre- tive approach to capitalize on their experience. spondence classes with similar demographics are reported on. Questionnaires and oral open-ended discussions were II. ACTIVE LEARNING APPROACHES USING used to assess the outcome of this effort. Overall the ap- ANDRAGOGY proach received positive reception while pointing out that correspondence students have full time jobs and active Although the early concepts on adult education go back learning in general requires more effort and time. -

CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY a Long March for Suffrage

CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY A long march for suffrage. Margaret Fuller was born in Cambridge in1810. By her late teens, she was considered a prodigy and equal or superior in intelligence to her male friends. As an adult she hosted “Conversations” for men and women on topics that ranged from women’s rights to philosophy. She joined Ralph Waldo Emerson in editing and writing for the Transcendentalist journal, The Dial from 1840-1842. It was in this publication that she wrote an article about women’s rights titled, “The Great Lawsuit,” which she would go on to expand into a book a few years later. In 1844, she moved to NYC to write for the New York Tribune. Her book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century was published in1845. She traveled to Europe as the Tribune’s foreign correspondent, the first woman to hold such a role. She died in a shipwreck off the coast of NY in July 1850 just as she was returning to life in the U.S. Her husband and infant also perished. It was hoped that she would be a leader in the equal rights and suffrage movements but her life was tragically cut short. 02 SARAH BURKS, CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL COMMISSION December 2019 CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY A long march for suffrage. Harriet A. Jacobs (1813-1897) was born into slavery in Edenton, NC. She escaped her sexually abusive owner in 1835 and lived in hiding for seven years. In 1842 she escaped to the north. She eventually was able to secure freedom for her children and herself. -

SSAWW-2021-Conference-Program-11-July-2021.Docx

2021 SSAWW Conference Schedule (Draft 11 July 2021) WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 3 Conference Registration: 4:00-8:00 p.m., Regency THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 4 Registration: 6:30 a.m.-4:00 p.m., Regency Book exhibition: 8:15 a.m.-5:00 p.m., Brightons Mentoring Breakfast: 7:00 a.m.-8:15 a.m., Hamptons Thursday, 8:30-9:45 a.m. Session 1A, North Whitehall “Gothic Ecologies: Alcott, Her Contexts, and Contemporaries” Sponsored by the Louisa May Alcott Society Chair: Sandra Harbert Petrulionis, Pennsylvania State University, Altoona ● "Never Mind the Boys": Gothic Persuasions of Jane Goodwin Austin and Louisa May Alcott Kari Miller, Perimeter College at Georgia State University ● Wealth, Handicaps, and Jewels: Alcott's Gothic Tales of Dis-Possession Monika Elbert, Montclair State University ● Alcott in the Cadre of Scribbling Women: 'Realizing' the Female Gothic for Nineteenth Century American Periodicals Wendy Fall, Marquette University Session 1B, Guilford “Pedagogy and the Archives (Part I)” Chair: TBD ● Commonplace Book Practices and the Digital Archive Kirsten Paine, University of Pittsburgh ● Making Literary Artifacts and Exhibits as Acts of Scholarship Mollie Barnes, University of South Carolina Beaufort ● "My dearest sweet Anna": Transcribing Laura Curtis Bullard's Love Letters to Anna Dickinson and Zooming to the Library of Congress Denise Kohn, Baldwin Wallace University ● Nineteenth Century Science of Surgery as Cure for the Greatest Curse Sigrid Schönfelder, Universität Passau 1 - DRAFT: 11 July 2021 Session 1C, Westminster (Need AV) “Recovering Abolitionist Lives and Histories” Chair: Laura L. Mielke, University of Kansas ● Audubon's Black Sisters Brigitte Fielder, University of Wisconsin-Madison ● Recovery Work and the Case of Fanny Kemble's Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation, 1838-39 Laura L. -

Constructing Womanhood: the Influence of Conduct Books On

CONSTRUCTING WOMANHOOD: THE INFLUENCE OF CONDUCT BOOKS ON GENDER PERFORMANCE AND IDEOLOGY OF WOMANHOOD IN AMERICAN WOMEN’S NOVELS, 1865-1914 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Colleen Thorndike May 2015 Copyright All rights reserved Dissertation written by Colleen Thorndike B.A., Francis Marion University, 2002 M.A., University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 2004 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Wesley Raabe, Associate Professor, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Babacar M’Baye, Associate Professor, Department of English Stephane Booth, Associate Provost Emeritus, Department of History Kathryn A. Kerns, Professor, Department of Psychology Accepted by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English James L. Blank, Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Conduct Books ............................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 2 : Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and Advice for Girls .......................................... 41 Chapter 3: Bands of Women: -

Before 1880, Through Excuses Only

CHAPTER ONE BEFORE 1880, THROUGH EXCUSES ONLY She is in the swim, but not of it. —Journalist magazine In 1890, only 4 percent of American journalists were women, and percentages in other writing fields were even lower.Those few who made a serious com- mitment to writing found their course severely constrained—by their educa- tion, family responsibilities, social codes, and isolation from other writers. Because of these limited freedoms and connections, American women in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries wrote by relying on some form of justifi- cation or rationalization, which varied with the decades, and they usually wrote professionally for only part of their adulthood. Cast in the insubstantial role of Non-Writer, a subset of the care-giving Woman, these writers were meant to address only women readers on narrowly defined women’s topics such as home- making while the genres and pronouncements of male Writers were shaping American intellectual culture. Although their choices were few, for women working within a patriarchal system without supportive networks or groups, these excuses and restrictive definitions did provide some space for writing. DURING THE COLONIAL PERIOD In the colonial period, women’s labor was frequently needed, in towns and certainly on the frontier, and it provided their means of securing a living when 1 2 A GROUP OF THEIR OWN left without father or husband. Some better educated single women and wid- ows worked in journalism—writing, editing, printing, and distributing news- papers while also taking on contract printing jobs. Elizabeth Glover of Cam- bridge, whose husband, the Reverend Jose Glover, died on the boat to America, operated the first printing press in North America (Marzolf 2). -

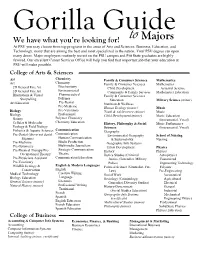

Gorilla Guide for Majors Activity

Gorilla Guide Gorilla Guide We have what you’re looking for! to Majors At PSU you may choose from top programs in the areas of Arts and Sciences, Business, Education, and Technology, many that are among the best and most specialized in the nation. Your PSU degree can open many doors. Major employers routinely recruit on the PSU campus and Pitt State graduates are highly favored. Our excellent Career Services Office will help you find that important job that your education at PSU will make possible. College of Arts & Sciences Art Chemistry Family & Consumer Sciences Mathematics Art Chemistry Family & Consumer Sciences Mathematics 2D General Fine Art Biochemistry Child Development Actuarial Science 3D General Fine Art Environmental Community & Family Services Mathematics Education Illustrations & Visual Pharmaceutical Family & Consumer Sciences Storytelling Polymer Education Military Science (minor) Art Education Pre-Dental Nutrition & Wellness Pre-Medicine Human Ecology (minor) Music Biology Pre-Veterinary Youth & Adolescence (minor) Music Biology Professional Child Development (minor) Music Education Botany Polymer Chemistry (Instrumental, Vocal) Cellular & Molecular Chemistry Education History, Philosophy & Social Music Performance Ecology & Field Biology Sciences (Instrumental, Vocal) Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences Communication Geography Pre-Dental (this is not dental Communication Environmental Geography School of Nursing hygiene) Human Communication & Sustainability Nursing Pre-Medicine Media Production Geographic Info Systems Pre-Optometry -

Pflanzen Aus Glas (Plants Made of Glass) 6-18 ©Naturwissenschaftlicher Verein Für Schwaben, Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Berichte des naturwiss. Vereins für Schwaben, Augsburg Jahr/Year: 2010 Band/Volume: 114 Autor(en)/Author(s): Mayer Andreas Artikel/Article: Pflanzen aus Glas (Plants made of glass) 6-18 ©Naturwissenschaftlicher Verein für Schwaben, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Berichte des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins für Schwaben 114. Bd. 2010 Andreas Mayer Pflanzen aus Glas (Plants made of glass) Zusammenfassung Die berühmte Harvard Universität besitzt ein angesehenes naturwissenschaftliches Museum das „Harvard Museum of Natural History“, welches jährlich rund 180.000 Besucher aus aller Welt anlockt. Die Hauptattraktion stellt eine einzigartige Sammlung von Pflanzenmodellen aus Glas dar. Prof. George Lincoln Goodale, der erste Direktor des Botanischen Museums von Harvard, wollte in den frühen 80er Jahren des 19. Jahr hunderts permanente Pflanzenmodelle aus Glas. Sie sollten zum einen die Schönheit des Pflanzenreichs in möglichst realistischer Form abbilden und zum anderen das ganze Jahr über zu Unterrichtszwecken genutzt werden. Ihm gelang es die beiden äußerst talentierten deutschen Glaskünstler, die sich bereits durch die Herstellung sehr realistischer Glasmodelle von marinen Invertebraten (wie etwa Quallen und See anemonen) einen Namen gemacht hatten, Leopold und seinen Sohn Rudolf Blaschka zur Herstellung von Pflanzen aus Glas zu überzeugen. Die Modelle wurden in den Jah ren 1886 bis 1936 exklusiv für die Harvard Universität mit damals üblichen Techniken gefertigt. Sie versetzten von da an den Betrachter durch ihre unbeschreibliche Schön heit und Detailtreue in großes Erstaunen. Die Finanzierung dieses Mammutprojekts übernahm Elizabeth C. Ware und ihre Tochter Mary Lee Ware zum Gedenken an Dr. -

Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: a Biographical and Contextual View Karen L

Andean Past Volume 7 Article 14 2005 Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: A Biographical and Contextual View Karen L. Mohr Chavez deceased Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Mohr Chavez, Karen L. (2005) "Alfred Kidder II in the Development of American Archaeology: A Biographical and Contextual View," Andean Past: Vol. 7 , Article 14. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol7/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALFRED KIDDER II IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY: A BIOGRAPHICAL AND CONTEXTUAL VIEW KAREN L. MOHR CHÁVEZ late of Central Michigan University (died August 25, 2001) Dedicated with love to my parents, Clifford F. L. Mohr and Grace R. Mohr, and to my mother-in-law, Martha Farfán de Chávez, and to the memory of my father-in-law, Manuel Chávez Ballón. INTRODUCTORY NOTE BY SERGIO J. CHÁVEZ1 corroborate crucial information with Karen’s notes and Kidder’s archive. Karen’s initial motivation to write this biography stemmed from the fact that she was one of Alfred INTRODUCTION Kidder II’s closest students at the University of Pennsylvania. He served as her main M.A. thesis This article is a biography of archaeologist Alfred and Ph.D. dissertation advisor and provided all Kidder II (1911-1984; Figure 1), a prominent necessary assistance, support, and guidance. -

Of American Ethnology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution

25 Dr. William C. Sturtevant Curator of American Ethnology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Dr. Donald Tuzin, Director Melanesian Archives University of California-San Diego Dr. John van Willigen Department of Anthropology University of Kentucky Dr. Joan Warnow-Blewett. Associate Director-Center of the History of Physics American Institute of Physics Dr. Annette B. Weiner, President American Anthropological Association Washington D.C. Dr. Thomas H. Wilson, Director Center for African Art New York, New York Ms. Nathalie F.S. Woodbury Shutesbury,Massachusetts Ms. Bonnie Wright. Chair ALA!Anthro and Soc. Sec of ACRL, 1989: "Anthropological Field Notes" Dr. John E. Yellen. Director Anthropology Program National Science Foundation VII. Announcements/Sources for the History of Archaeology The Robert F. HeizerPapers are accessible althoughthe registeris not totallyfinished. Researchers need to contact Sheila O'Neil at the BancroftLibrary. University of California Berkeley. The Society for Industrial Archaeology and the Historic American Engineering Record of the National Park Service sponsored a fellowship (closing date 28 February 1992) for those preparing monographs or books on AmeIican industrial engineering history using material culture (structures. machines, and other artifacts) as as basis for the study. For more information write David L. Salay, Department of History, Montana State University. Boseman, Montana 59717. 26 James Kenworthy(Archaeology, Nottingham University) is editing a volume titled "Histories of Archaeology". He is currently soliciting papers for the volume. Papers of a historiographic nature will look at how archaeology hasbeen written now and in the past Papers can be biographical, thematic(science, gender, nationalism), of any periodor place. Closing date: September 1992. -

Important Women in United States History (Through the 20Th Century) (A Very Abbreviated List)

Important Women in United States History (through the 20th century) (a very abbreviated list) 1500s & 1600s Brought settlers seeking religious freedom to Gravesend at New Lady Deborah Moody Religious freedom, leadership 1586-1659 Amsterdam (later New York). She was a respected and important community leader. Banished from Boston by Puritans in 1637, due to her views on grace. In Religious freedom of expression 1591-1643 Anne Marbury Hutchinson New York, natives killed her and all but one of her children. She saved the life of Capt. John Smith at the hands of her father, Chief Native and English amity 1595-1617 Pocahontas Powhatan. Later married the famous John Rolfe. Met royalty in England. Thought to be North America's first feminist, Brent became one of the Margaret Brent Human rights; women's suffrage 1600-1669 largest landowners in Maryland. Aided in settling land dispute; raised armed volunteer group. One of America's first poets; Bradstreet's poetry was noted for its Anne Bradstreet Poetry 1612-1672 important historic content until mid-1800s publication of Contemplations , a book of religious poems. Wife of prominent Salem, Massachusetts, citizen, Parsons was acquitted Mary Bliss Parsons Illeged witchcraft 1628-1712 of witchcraft charges in the most documented and unusual witch hunt trial in colonial history. After her capture during King Philip's War, Rowlandson wrote famous Mary Rowlandson Colonial literature 1637-1710 firsthand accounting of 17th-century Indian life and its Colonial/Indian conflicts. 1700s A Georgia woman of mixed race, she and her husband started a fur trade Trading, interpreting 1700-1765 Mary Musgrove with the Creeks. -

Updated 2019 Completemedia

April 15, 2019 Dear Members of the Media, On behalf of the Boston Athletic Association, principal sponsor John Hancock, and all of our sponsors and supporters, we welcome you to the City of Boston and the 123rd running of the Boston Marathon. As the oldest annually contested marathon in the world, the Boston Marathon represents more than a 26.2-mile footrace. The roads from Hopkinton to Boston have served as a beacon for well over a century, bringing those from all backgrounds together to celebrate the pursuit of athletic excellence. From our early beginnings in 1897 through this year’s 123rd running, the Boston Marathon has been an annual tradition that is on full display every April near and far. We hope that all will be able to savor the spirit of the Boston Marathon, regardless whether you are an athlete or volunteer, spectator or member of the media. Race week will surely not disappoint. The race towards Boylston Street will continue to showcase some of the world’s best athletes. Fronting the charge on Marathon Monday will be a quartet of defending champions who persevered through some of the harshest weather conditions in race history twelve months ago. Desiree Linden, the determined and resilient American who snapped a 33-year USA winless streak in the women’s open division, returns with hopes of keeping her crown. Linden has said that last year’s race was the culmination of more than a decade of trying to tame the beast of Boston – a race course that rewards those who are both patient and daring.