The Grateful Dead's Development of Models for Rock Improvisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

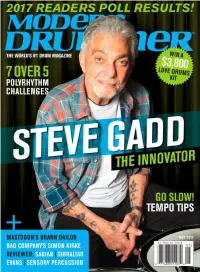

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

Snarky Puppy Snarky Puppy Snarky Puppy

SNARKY PUPPY GENRE: ELECTRIC JAZZ/FUNK/INSTRUMENTAL Displaying a rare and delicate mixture of sophisticated composition, harmony and improvisation, Fusion-influenced jam band Snarky Puppy make exploratory jazz, rock, and funk. Formed in Denton, Texas in 2004, Snarky Puppy feature a wide-ranging group of nearly 40 musicians known affectionately as “The Fam,” centered around bassist, composer and bandleader Michael League. Comparable Artists: Medeski, Martin & Wood, Brad Mehldau, Weather Report, Steely Dan AWARDS • 2014 Grammy winner for “Best R&B Performance” • Voted “Best Jazz Group” in Downbeat’s 2015 Reader’s Poll/Cover of February 2016 issue •“Best New Artist” and “Best Electric/Jazz-Rock/Contemporary Group/Artist” in Jazz Times 2014 Reader’s Poll PRESS • “Emotionally heroic compositions…At the heart of Snarky Puppy’s music lies an incredible humanity,…a soulful appeal for fans of all ages” – Electronic Musician • “This 12-piece collective stands out with furious commitment to defying musical categories. The music is no joke.” – LA Times • Featured in the New York Times, NPR, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Relix, SF Weekly, Modern Drummer, and more TOUR • Played over 300 performances over the last two years on four continents • Snarky Puppy are devoted to music education holding clinics and workshops with students in-between international tourdates PEAK PERFORMANCE • Their last album, Sylva, garnered a #1-chart debut simultaneously on both Billboard’s Jazz and Heatseekers Charts • Snarky Puppy streaming music fans are primarily paid/premium subscribers to services such as Spotify, Google Play and Apple Music and listen on desktop and mobile devices (49%/51% split) • All of Snarky Puppy’s albums are recorded 100% live often with in-studio audiences present DEMO Male (82%)/Female (18%) Age: 18-34 (73%) http://www.impulse-label.com/ LINKS OFFICIAL WEBSITE 222,852 fans 30.8K followers 62.8K followers 28K 91K (Snarky Puppy) (GroundUP Music). -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

French Stewardship of Jazz: the Case of France Musique and France Culture

ABSTRACT Title: FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE Roscoe Seldon Suddarth, Master of Arts, 2008 Directed By: Richard G. King, Associate Professor, Musicology, School of Music The French treat jazz as “high art,” as their state radio stations France Musique and France Culture demonstrate. Jazz came to France in World War I with the US army, and became fashionable in the 1920s—treated as exotic African- American folklore. However, when France developed its own jazz players, notably Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli, jazz became accepted as a universal art. Two well-born Frenchmen, Hugues Panassié and Charles Delaunay, embraced jazz and propagated it through the Hot Club de France. After World War II, several highly educated commentators insured that jazz was taken seriously. French radio jazz gradually acquired the support of the French government. This thesis describes the major jazz programs of France Musique and France Culture, particularly the daily programs of Alain Gerber and Arnaud Merlin, and demonstrates how these programs display connoisseurship, erudition, thoroughness, critical insight, and dedication. France takes its “stewardship” of jazz seriously. FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE By Roscoe Seldon Suddarth Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2008 Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Richard King, Musicology Division, Chair Professor Robert Gibson, Director of the School of Music Professor Christopher Vadala, Director, Jazz Studies Program © Copyright by Roscoe Seldon Suddarth 2008 Foreword This thesis is the result of many years of listening to the jazz broadcasts of France Musique, the French national classical music station, and, to a lesser extent, France Culture, the national station for literary, historical, and artistic programs. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

Event Details

This document will assist you with the right choices of music for your event; it contains examples of popular songs used during successful parties. Song Artist Bom Bom Sam and The Womp Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Treasure Bruno Mars Feel This Moment Pitbull & Christina Aguliera Get Lucky Pharrell & Daft Punk Shook Me All Night Long ACDC Jessie Girl Rick Springfield Nutbush Ike & Tina Loveshack B52’s Eagle Rock Daddy Cool Tequila Champs I’m On My way Proclaimers Swing The Mood Jivebunny I wanna Dance With Somebody Whitney Houston Moves Like Jagger Maroon five Timber Ke$ha Jump Girls Aloud Superstitious Stevie Wonder Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Blondie Hot Stuff Donna Summers My Sharona The Knack It’s Tricky Run DMC Summer of 69 Bryan Adams Mr Jones County Crows Are You Going To Be My Girl Jet Sex On Fire Kings Of Leon Blame On Boogie Jackson Five 0402 277 208 | [email protected] | www.djdiggler.com.au | 21 Higgs Ct, Wynnum West, Queensland, Australia 4178 Grease Mega Mix Grease Soundtrack Jailhouse Rock Elvis Shoop Shoop Song Cher 500 Miles Proclaimers Single Ladies Beyonce Crazy In Love Beyonce Sexy and I Know It LMFAO What Makes You Beautiful One direction All Summer Long Kid Rock Bad Romance Lady Ga Ga Party Rock Anthem LMFAO Joker and Thief Wolfmother Lonely Boy Black Keys Raise Your Glass Pink Take On Me Ah Ha We Found Love Rihanna Wish You Well Bernard Fanning April Sun Dragon Nips Are Getting Bigger Mental As Anything Groove Is In The Heart Dee Lite Groove Jet Spiller Low Flo Rider Dynamite Taio Cruz Jump Around House -

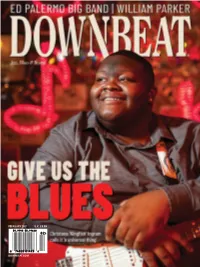

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Blues in the Blood a M U E S L B M L E O O R D

March 2011 | No. 107 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com J blues in the blood a m u e s l b m l e o o r d Johnny Mandel • Elliott Sharp • CAP Records • Event Calendar In his play Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare wrote, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” It is a lovely sentiment but one with which we agree only partially. So with that introduction, we are pleased to announce that as of this issue, the gazette formerly known as AllAboutJazz-New York will now be called The New York City Jazz Record. It is a change that comes on the heels of our separation New York@Night last summer from the AllAboutJazz.com website. To emphasize that split, we felt 4 it was time to come out, as it were, with our own unique identity. So in that sense, a name is very important. But, echoing Shakespeare’s idea, the change in name Interview: Johnny Mandel will have no impact whatsoever on our continuing mission to explore new worlds 6 by Marcia Hillman and new civilizations...oh wait, wrong mission...to support the New York City and international jazz communities. If anything, the new name will afford us new Artist Feature: Elliott Sharp opportunities to accomplish that goal, whether it be in print or in a soon-to-be- 7 by Martin Longley expanded online presence. We are very excited for our next chapter and appreciate your continued interest and support. On The Cover: James Blood Ulmer But back to the business of jazz. -

Children of the Heav'nly King: Religious Expression in the Central

Seldom has the folklore of a particular re- CHILDREN lar weeknight gospel singings, which may fea gion been as exhaustively documented as that ture both local and regional small singing of the central Blue Ridge Mountains. Ex- OF THE groups, tent revival meetings, which travel tending from southwestern Virginia into north- from town to town on a weekly basis, religious western North Carolina, the area has for radio programs, which may consist of years been a fertile hunting ground for the HE A"' T'NLV preaching, singing, a combination of both, most popular and classic forms of American .ft.V , .1 the broadcast of a local service, or the folklore: the Child ballad, the Jack tale, the native KING broadcast of a pre-recorded syndicated program. They American murder ballad, the witch include the way in which a church tale, and the fiddle or banjo tune. INTRODUCTORY is built, the way in which its interi- Films and television programs have or is laid out, and the very location portrayed the region in dozens of of the church in regard to cross- stereotyped treatments of mountain folk, from ESS A ....y roads, hills, and cemetery. And finally, they include "Walton's mountain" in the north to Andy Griffith's .ft. the individual church member talking about his "Mayberry" in the south. FoIklor own church's history, interpreting ists and other enthusiasts have church theology, recounting char been collecting in the region for acter anecdotes about well-known over fifty years and have amassed preachers, exempla designed to miles of audio tape and film foot illustrate good stewardship or even age.