49 Revisiting Russell's Theory of Descriptions by Patrick Henning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Denying a Dualism: Goodman's Repudiation of the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction

Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 28, 2004, 226-238. Denying a Dualism: Goodman’s Repudiation of the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction Catherine Z. Elgin The analytic synthetic/distinction forms the backbone of much modern Western philosophy. It underwrites a conception of the relation of representations to reality which affords an understanding of cognition. Its repudiation thus requires a fundamental reconception and perhaps a radical revision of philosophy. Many philosophers believe that the repudiation of the analytic/synthetic distinction and kindred dualisms constitutes a major loss, possibly even an irrecoverable loss, for philosophy. Nelson Goodman thinks otherwise. He believes that it liberates philosophy from unwarranted restrictions, creating opportunities for the development of powerful new approaches to and reconceptions of seemingly intractable problems. In this article I want to sketch some of the consequences of Goodman’s reconception. My focus is not on Goodman’s reasons for denying the dualism, but on some of the ways its absence affects his position. I do not contend that the Goodman obsessed over the issue. I have no reason to think that the repudiation of the distinction was a central factor in his intellectual life. But by considering the function that the analytic/synthetic distinction has performed in traditional philosophy, and appreciating what is lost and gained in repudiating it, we gain insight into Goodman’s contributions. I begin then by reviewing the distinction and the conception of philosophy it supports. The analytic/synthetic distinction is a distinction between truths that depend entirely on meaning and truths that depend on both meaning and fact. In the early modern period, it was cast as a distinction between relations of ideas and matters of fact. -

Philosophical Logic 2018 Course Description (Tentative) January 15, 2018

Philosophical Logic 2018 Course description (tentative) January 15, 2018 Valentin Goranko Introduction This 7.5 hp course is mainly intended for students in philosophy and is generally accessible to a broad audience with basic background on formal classical logic and general appreciation of philosophical aspects of logic. Practical information The course will be given in English. It will comprise 18 two-hour long sessions combining lectures and exercises, grouped in 2 sessions per week over 9 teaching weeks. The weekly pairs of 2-hour time slots (incl. short breaks) allocated for these sessions, will be on Mondays during 10.00-12.00 and 13.00-15.00, except for the first lecture. The course will begin on Wednesday, April 4, 2018 (Week 14) at 10.00 am in D220, S¨odra huset, hus D. Lecturer's info: Name: Valentin Goranko Email: [email protected] Homepage: http://www2.philosophy.su.se/goranko Course webpage: http://www2.philosophy.su.se/goranko/Courses2018/PhilLogic-2018.html Prerequisites The course will be accessible to a broad audience with introductory background on classical formal logic. Some basic knowledge of modal logics would be an advantage but not a prerequisite. Brief description Philosophical logic studies a variety of non-classical logical systems intended to formalise and reason about various philosophical concepts and ideas. They include a broad family of modal logics, as well as many- valued, intuitionistic, relevant, conditional, non-monotonic, para-consistent, etc. logics. Modal logics extend classical logic with additional intensional logical operators, reflecting different modes of truth, including alethic, epistemic, doxastic, temporal, deontic, agentive, etc. -

Introduction to Philosophy. Social Studies--Language Arts: 6414.16. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 086 604 SO 006 822 AUTHOR Norris, Jack A., Jr. TITLE Introduction to Philosophy. Social Studies--Language Arts: 6414.16. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 20p.; Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; Grade 10; Grade 11; Grade 12; *Language Arts; Learnin4 Activities; *Logic; Non Western Civilization; *Philosophy; Resource Guides; Secondary Grades; *Social Studies; *Social Studies Units; Western Civilization IDENTIFIERS *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT Western and non - western philosophers and their ideas are introduced to 10th through 12th grade students in this general social studies Quinmester course designed to be used as a preparation for in-depth study of the various schools of philosophical thought. By acquainting students with the questions and categories of philosophy, a point of departure for further study is developed. Through suggested learning activities the meaning of philosopky is defined. The Socratic, deductive, inductive, intuitive and eclectic approaches to philosophical thought are examined, as are three general areas of philosophy, metaphysics, epistemology,and axiology. Logical reasoning is applied to major philosophical questions. This course is arranged, as are other quinmester courses, with sections on broad goals, course content, activities, and materials. A related document is ED 071 937.(KSM) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY U S DEPARTMENT EDUCATION OF HEALTH. NAT10N41 -

Curriculum Vitae

BAS C. VAN FRAASSEN Curriculum Vitae Last updated 3/6/2019 I. Personal and Academic History .................................................................................................................... 1 List of Degrees Earned ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Title of Ph.D. Thesis ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 Positions held ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Invited lectures and lecture series ........................................................................................................................................ 1 List of Honors, Prizes ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Research Grants .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Non-Academic Publications ................................................................................................................................................ 5 II. Professional Activities ................................................................................................................................. -

Puzzles About Descriptive Names Edward Kanterian

Puzzles about descriptive names Edward Kanterian To cite this version: Edward Kanterian. Puzzles about descriptive names. Linguistics and Philosophy, Springer Verlag, 2010, 32 (4), pp.409-428. 10.1007/s10988-010-9066-1. hal-00566732 HAL Id: hal-00566732 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00566732 Submitted on 17 Feb 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Linguist and Philos (2009) 32:409–428 DOI 10.1007/s10988-010-9066-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Puzzles about descriptive names Edward Kanterian Published online: 17 February 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 Abstract This article explores Gareth Evans’s idea that there are such things as descriptive names, i.e. referring expressions introduced by a definite description which have, unlike ordinary names, a descriptive content. Several ignored semantic and modal aspects of this idea are spelled out, including a hitherto little explored notion of rigidity, super-rigidity. The claim that descriptive names are (rigidified) descriptions, or abbreviations thereof, is rejected. It is then shown that Evans’s theory leads to certain puzzles concerning the referential status of descriptive names and the evaluation of identity statements containing them. -

The Analytic-Synthetic Distinction and the Classical Model of Science: Kant, Bolzano and Frege

Synthese (2010) 174:237–261 DOI 10.1007/s11229-008-9420-9 The analytic-synthetic distinction and the classical model of science: Kant, Bolzano and Frege Willem R. de Jong Received: 10 April 2007 / Revised: 24 July 2007 / Accepted: 1 April 2008 / Published online: 8 November 2008 © The Author(s) 2008. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This paper concentrates on some aspects of the history of the analytic- synthetic distinction from Kant to Bolzano and Frege. This history evinces con- siderable continuity but also some important discontinuities. The analytic-synthetic distinction has to be seen in the first place in relation to a science, i.e. an ordered system of cognition. Looking especially to the place and role of logic it will be argued that Kant, Bolzano and Frege each developed the analytic-synthetic distinction within the same conception of scientific rationality, that is, within the Classical Model of Science: scientific knowledge as cognitio ex principiis. But as we will see, the way the distinction between analytic and synthetic judgments or propositions functions within this model turns out to differ considerably between them. Keywords Analytic-synthetic · Science · Logic · Kant · Bolzano · Frege 1 Introduction As is well known, the critical Kant is the first to apply the analytic-synthetic distinction to such things as judgments, sentences or propositions. For Kant this distinction is not only important in his repudiation of traditional, so-called dogmatic, metaphysics, but it is also crucial in his inquiry into (the possibility of) metaphysics as a rational science. Namely, this distinction should be “indispensable with regard to the critique of human understanding, and therefore deserves to be classical in it” (Kant 1783, p. -

Description Logics—Basics, Applications, and More

Description Logics|Basics, Applications, and More Ian Horrocks Information Management Group University of Manchester, UK Ulrike Sattler Teaching and Research Area for Theoretical Computer Science RWTH Aachen, Germany RWTH Aachen 1 Germany Overview of the Tutorial • History and Basics: Syntax, Semantics, ABoxes, Tboxes, Inference Problems and their interrelationship, and Relationship with other (logical) formalisms • Applications of DLs: ER-diagrams with i.com demo, ontologies, etc. including system demonstration • Reasoning Procedures: simple tableaux and why they work • Reasoning Procedures II: more complex tableaux, non-standard inference prob- lems • Complexity issues • Implementing/Optimising DL systems RWTH Aachen 2 Germany Description Logics • family of logic-based knowledge representation formalisms well-suited for the representation of and reasoning about ➠ terminological knowledge ➠ configurations ➠ ontologies ➠ database schemata { schema design, evolution, and query optimisation { source integration in heterogeneous databases/data warehouses { conceptual modelling of multidimensional aggregation ➠ : : : • descendents of semantics networks, frame-based systems, and KL-ONE • aka terminological KR systems, concept languages, etc. RWTH Aachen 3 Germany Architecture of a Standard DL System Knowledge Base I N Terminology F E I R Father = Man u 9 has child.>... N E T Human = Mammal. u Biped . N E Description C R E F Logic A Concrete Situation S C Y E John:Human u Father S John has child Bill . T . E M RWTH Aachen 4 Germany Introduction -

The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): Mathematician, Logician, and Philosopher

Louis deRosset { Spring 2019 Russell: The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): mathematician, logician, and philosopher. He's one of the founders of analytic philosophy. \On Denoting" is a founding document of analytic philosophy. It is a paradigm of philosophical analysis. An analysis of a concept/phenomenon c: a recipe for eliminating c-vocabulary from our theories which still captures all of the facts the c-vocabulary targets. FOR EXAMPLE: \The Name View Analysis of Identity." 2. Russell's target: Denoting Phrases By a \denoting phrase" I mean a phrase such as any one of the following: a man, some man, any man, every man, all men, the present King of England, the present King of France, the centre of mass of the Solar System at the first instant of the twentieth century, the revolution of the earth round the sun, the revolution of the sun round the earth. (479) Includes: • universals: \all F 's" (\each"/\every") • existentials: \some F " (\at least one") • indefinite descriptions: \an F " • definite descriptions: \the F " Later additions: • negative existentials: \no F 's" (480) • Genitives: \my F " (\your"/\their"/\Joe's"/etc.) (484) • Empty Proper Names: \Apollo", \Hamlet", etc. (491) Russell proposes to analyze denoting phrases. 3. Why Analyze Denoting Phrases? Russell's Project: The distinction between acquaintance and knowledge about is the distinction between the things we have presentation of, and the things we only reach by means of denoting phrases. [. ] In perception we have acquaintance with the objects of perception, and in thought we have acquaintance with objects of a more abstract logical character; but we do not necessarily have acquaintance with the objects denoted by phrases composed of words with whose meanings we are ac- quainted. -

Russell's Theory of Descriptions

Russell’s theory of descriptions PHIL 83104 September 5, 2011 1. Denoting phrases and names ...........................................................................................1 2. Russell’s theory of denoting phrases ................................................................................3 2.1. Propositions and propositional functions 2.2. Indefinite descriptions 2.3. Definite descriptions 3. The three puzzles of ‘On denoting’ ..................................................................................7 3.1. The substitution of identicals 3.2. The law of the excluded middle 3.3. The problem of negative existentials 4. Objections to Russell’s theory .......................................................................................11 4.1. Incomplete definite descriptions 4.2. Referential uses of definite descriptions 4.3. Other uses of ‘the’: generics 4.4. The contrast between descriptions and names [The main reading I gave you was Russell’s 1919 paper, “Descriptions,” which is in some ways clearer than his classic exposition of the theory of descriptions, which was in his 1905 paper “On Denoting.” The latter is one of the optional readings on the web site, and I reference it below sometimes as well.] 1. DENOTING PHRASES AND NAMES Russell defines the class of denoting phrases as follows: “By ‘denoting phrase’ I mean a phrase such as any one of the following: a man, some man, any man, every man, all men, the present king of England, the centre of mass of the Solar System at the first instant of the twentieth century, the revolution of the earth around the sun, the revolution of the sun around the earth. Thus a phrase is denoting solely in virtue of its form.” (‘On Denoting’, 479) Russell’s aim in this article is to explain how expressions like this work — what they contribute to the meanings of sentences containing them. -

Willard Van Orman Quine: the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction

Willard Van Orman Quine: The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction Willard Van Orman Quine was one of the most well-known American “analytic” philosophers of the twentieth century. He made significant contributions to many areas of philosophy, including philosophy of language, logic, epistemology, philosophy of science, and philosophy of mind/psychology (behaviorism). However, he is best known for his rejection of the analytic/synthetic distinction. Technically, this is the distinction between statements true in virtue of the meanings of their terms (like “a bachelor is an unmarried man”) and statements whose truth is a function not simply of the meanings of terms, but of the way the world is (such as, “That bachelor is wearing a grey suit”). Although a contentious thesis, analyticity has been a popular explanation, especially among empiricists, both for the necessity of necessary truths and for the a priori knowability of some truths. Thus, in some contexts “analytic truth,” “necessary truth,” and “a priori truth” have been used interchangeably, and the analytic/synthetic distinction has been treated as equivalent to the distinctions between necessary and contingent truths, and between a priori and a posteriori (or empirical) truths. Empirical truths can be known only by empirical verification, rather than by “unpacking” the meanings of the terms involved, and are usually thought to be contingent. Quine wrestled with the analytic/synthetic distinction for years, but he did not make his thoughts public until 1950, when he delivered his paper, “The Two Dogmas of Empiricism” at a meeting of the American Philosophical Association. In this paper, Quine argues that all attempts to define and understand analyticity are circular. -

Theory of Knowledge in Britain from 1860 to 1950

Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication Volume 4 200 YEARS OF ANALYTICAL PHILOSOPHY Article 5 2008 Theory Of Knowledge In Britain From 1860 To 1950 Mathieu Marion Université du Quéebec à Montréal, CA Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/biyclc This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Marion, Mathieu (2008) "Theory Of Knowledge In Britain From 1860 To 1950," Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication: Vol. 4. https://doi.org/10.4148/biyclc.v4i0.129 This Proceeding of the Symposium for Cognition, Logic and Communication is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theory of Knowledge in Britain from 1860 to 1950 2 The Baltic International Yearbook of better understood as an attempt at foisting on it readers a particular Cognition, Logic and Communication set of misconceptions. To see this, one needs only to consider the title, which is plainly misleading. The Oxford English Dictionary gives as one August 2009 Volume 4: 200 Years of Analytical Philosophy of the possible meanings of the word ‘revolution’: pages 1-34 DOI: 10.4148/biyclc.v4i0.129 The complete overthrow of an established government or social order by those previously subject to it; an instance of MATHIEU MARION this; a forcible substitution of a new form of government. -

Using Russell's Theory of Descriptions to S

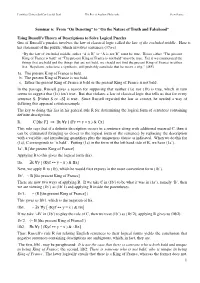

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú The Rise of Analytic Philosophy Scott Soames Seminar 6: From “On Denoting” to “On the Nature of Truth and Falsehood” Using Russell’s Theory of Descriptions to Solve Logical Puzzles One of Russell’s puzzles involves the law of classical logic called the law of the excluded middle. Here is his statement of the puzzle, which involves sentences (37a-c). “By the law of excluded middle, either “A is B” or “A is not B” must be true. Hence either “The present King of France is bald” or “The present King of France is not bald” must be true. Yet if we enumerated the things that are bald and the things that are not bald, we should not find the present King of France in either list. Hegelians, who love a synthesis, will probably conclude that he wears a wig.” (485) 1a. The present King of France is bald. b. The present King of France is not bald. c. Either the present King of France is bald or the present King of France is not bald. In the passage, Russell gives a reason for supposing that neither (1a) nor (1b) is true, which in turn seems to suggest that (1c) isn’t true. But that violates a law of classical logic that tells us that for every sentence S, ⎡Either S or ~S⎤ is true. Since Russell regarded the law as correct, he needed a way of defusing this apparent counterexample. The key to doing this lies in his general rule R for determining the logical form of sentences containing definite descriptions.