Manna Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Francis of Assisi Church

Second Sunday of Advent St. Francis December 8, 2019 Mass Schedule of Saturday 5:00 p.m. Cantor Sunday 8:00 a.m. Cantor Assisi Church 9:30 a.m. Cantor/Choir 11:15 a.m. Contemporary Choir 5:00 p.m. Youth Community 6701 Muncaster Mill Road Daily 9:00 a.m. Monday - Saturday Derwood, MD 20855 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, followed by Novena Phone: 301-840-1407 Fax: 301-258-5080 First Friday Mass - 7:30 p.m. http://www.sfadw.org Penance: Saturday 3:30-4:30 p.m. or by appointment CHAIRPERSON FINANCE COUNCIL: PASTOR: Reverend John J. Dillon George Beall . 301-253-8740 PARISH PASTORAL COUNCIL CONTACT: PERMANENT DEACONS: Alicia Church . 301-520-6683 Deacon James Datovech Questions for Parish Council e-mail Deacon Daniel Finn [email protected] Deacon Wilberto Garcia COORDINATOR OF LITURGY: Deacon James McCann Joan Treacy . .. .. 301-774-1132 RELIGIOUS EDUCATION: . 301-258-9193 Susan Anderson, Director Marie Yeast & Melisa Biedron, Admin. Assistants SOCIAL CONCERNS/ADULT FAITH FORMATION Anthony Bosnick, Director . .. 301-840-1407 MUSIC MINISTRY: Janet Pate, Director. 301-840-1407 YOUTH MINISTRY: Sarah Seyed-Ali, Youth Minister. -. 301-948-9167 COMMUNICATIONS : Melissa Egan, Coordinator. 301-840-1407 PARISH OFFICE: . 301-840-1407 Donna Zezzo, Parish Secretary BAPTISMS: Sunday at 1:00 p.m. No Baptisms are held the 1st Sunday of the month. Call Parish Office to set up an appointment with our Pastor. MARRIAGE/PRE-CANA: Call Parish Office. At least 6 months advance notice with our Pastor.. SICK CALLS: Please notify us concerning any parishioners who are sick or homebound, in hospitals or nursing homes. -

U.S. Catholic Mission Handbook 2006

U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION HANDBOOK 2006 Mission Inventory 2004 – 2005 Tables, Charts and Graphs Resources Published by the U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION 3029 Fourth St., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202 – 884 – 9764 Fax: 202 – 884 – 9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION HANDBOOK 2006 Mission Inventory 2004 – 2005 Tables, Charts and Graphs Resources ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Published by the U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION 3029 Fourth St., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202 – 884 – 9764 Fax: 202 – 884 – 9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org Additional copies may be ordered from USCMA. USCMA 3029 Fourth Street., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202-884-9764 Fax: 202-884-9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org COST: $4.00 per copy domestic $6.00 per copy overseas All payments should be prepaid in U.S. dollars. Copyright © 2006 by the United States Catholic Mission Association, 3029 Fourth St, NE, Washington, DC 20017-1102. 202-884-9764. [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE UNITED STATES CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION (USCMA)Purpose, Goals, Activities .................................................................................iv Board of Directors, USCMA Staff................................................................................................... v Past Presidents, Past Executive Directors, History ..........................................................................vi Part II: The U.S. -

Jordan Seminary

The Many Menominee Manifestations (Try saying that three times fast!) The USA Province of the Society of the Divine Savior has a lengthy history of buying “unique” properties that most people would NEVER think about for religious usage. We turned them into religious places anyway! Two provincials in particular – Fr. Bede Friedrich (1931-1936 / 1939-1947) and Fr. Paul Schuster (1953-1959) – had a knack for finding odd establishments and envisioning religious uses for them. (Many of those stories are already familiar and have been written about in some of our past Archives’ history pages: a “Buffalo Farm” became a seminary; a mud-bath resort was turned into a college; a dairy was transformed into a parish; a resort hotel – turned “National Swine Palace” – became our Novitiate; and an army barracks was used for a boys’ high school.) Another such property that underwent numerous transformations was in Menominee, Michigan. In this small city on the border of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and the state of Wisconsin, a set of buildings near the county’s tiny airport saw a variety of uses over the years – not just before the Salvatorians purchased it, but even while we owned it! Menominee County School of Agriculture – 1907-1929 Built in 1907, this county school was authorized by the state legislature to develop scientific agricultural methods for the farmers in the Upper Peninsula. Until 1925, when the economic situation across the country began to shift, the school was operated under county supervision and with county funds. The state took over the operations for the next four years, but the failing economy that would lead to the Great Depression forced even the state to close the school in 1929. -

SDS Contributions

Contributions on Salvatorian History, Charism, and Spirituality Volume Twelve Key Elements Contributions on Salvatorian History, Charism, and Spirituality Volume Twelve Key Elements A Project of the Joint History and Charism Committee Ms. Janet E Bitzan, SDS Ms. Sue Haertel, SDS Sr. Nelda Hernandez, SDS Fr. Michael Hoffman, SDS Fr. Patric Nikolas, SDS Sr. Barbara Reynolds, SDS Mr. Anthony Scola, SDS Sr. Carol Thresher, SDS With Permission of the Superiors Sr. Beverly Heitke, SDS Provincial of the Congregation of the Sisters of the Divine Savior Mrs. Jaqueline White, SDS National Director of the Lay Salvatorians Fr. Jeff Wocken, SDS Provincial of the Society of the Divine Savior February, 2020 Contents Introduction . v Key Element: Charism . 1 Universality in the Family Charter and its Roots in Father Jordan . .3 Ms. Janet Bitzan, SDS Our Salvation In Jesus Christ . .11 Fr. Luis Alfredo Escalante, SDS Towards a Salvatorian Theory of Salvation in the African Perspective . 23 Fr. Marcel Mukadi Kabisay, SDS Toward a Salvatorian Theology of Salvation. .41 Fr. Thomas Perrin, SDS Exploring Universality as Inclusive Love. .49 Sr. Carol Thresher, SDS Signs of the Presence of the Holy Spirit in the Society of the Divine Savior . .63 Fr. Milton Zonta, SDS The Holy Spirit in Early Salvatorian History. .75 Sr. Carol Thresher, SDS Key Element: Mission. 91 The Salvatorian Family Charter and the Kingdom of God . .93 Sr. Rozilde Maria Binotto, SDS, and Sr. Therezinha Joana Rasera, SDS Salvatorian Mission for the Signs of the Time . .105 Sr. Dinusha Fernando, SDS Living in the “Now”: A Salvatorian Response to the Signs of the Times . -

USA Mission Newsletter

S A L V A T O R I A N S #5 First Experience in America It’s a blessing, and as a Salvatorian, I really feel a sense of Universality. Behold how good and pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity. I am very grateful for Greetings….. the lovely support and help of the provincial, his council, My name is Fr. John Tigatiga, SDS from Tanzania, Mission board members and the Salvatorian family of East Africa. I was born on the 20th of June, 1983, USA. Thanks to the Bishops of the different dioceses in ordained as priest in June 2015, and spent the next USA who always invite our congregation to participate in year as an assistant Procurator and Pastor of St. the mission appeals. Have fun! Maurus Parish at Kurasini, Dar es Salaam. In May Fr. John Tigatiga, SDS 2018, I was sent to Milwaukee, Wisconsin to begin Mission Director my new job as a Mission Director. Currently I am working in the Mission office as well as pursuing Preparation of a New Farming Site in St. Joseph my graduate studies in Philosophy at Marquette Formation Community University. Thank You Donors! First is always first! Every person who travels in a The Salvatorians are developing a new 50 acre farm area place where he has never been before, must have in St. Joseph Parish Namiungo. The preliminary some exciting and incredible stories and activities included preparation of the site, measuring the experiences that they love to share. In my case, I've site and dividing it into acres for easy workmanship. -

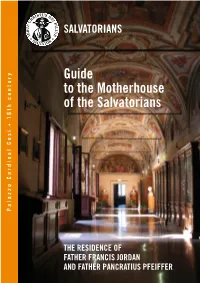

Guide to the Motherhouse of the Salvatorians

SALVATORIANS Guide to the Motherhouse of the Salvatorians 16th century • Palazzo Cardinal Cesi THE RESIDENCE OF FATHER FRANCIS JORDAN AND FATHER PANCRATIUS PFEIFFER Fr. Francis Mary of the Cross Jordan Welcome to the Motherhouse of the Society of the Divine Savior (Salvatorians). We invite you to discover our Founder as we describe the distinctiveness of the various spaces in this palazzo and as we tell you about our mission. 3 Aerial view of Palazzo Cesi Photo from 1920 prior to Via della Conciliazione Salvatorians in the Savior, Father Francis Mary of the Cross Jordan history of Palazzo Cesi (1848-1918). Upon seeing the sumptuousness of the palazzo, The Palazzo Cesi is located in an area where the one might ask: How could a poor and humble Roman philosopher and statesman Seneca had his religious, like Fr. Jordan, permit himself the luxury Father Francis Jordan house. Cardinal Francesco Armellini constructed it at of buying this building? … The story is long Palazzo Cesi today the beginning of 1500, by enlarging a building dating but we will provide a brief synthesis. from 1400. In 1527, during the Pillage of Rome, Father Francis Jordan founded the Society of the the Lanzichenecchi invaded and looted the palazzo Divine Savior on 8 December 1881 in the chapel requiring the Cardinal to flee to Castel Sant’Angelo where St. Brigid of Sweden died, in a small palazzo at where he died a few months later. Piazza Farnese. But as the number of members grew In 1565, Pierdonato and Angelo Cesi bought the rapidly in the Society, he was obliged in 1882 to rent building and they had it restructured completely by some rooms in the Palazzo Cesi which at that time Martino Longhi the Elder between 1570 and 1577. -

Gosford Parish

SIXTH SUNDAY OF EASTER YEAR B 9 MAY, 2021 Gosford Parish The Communities of St Patrick’s East Gosford, St Francis of Assisi Somersby & Holy Trinity Spencer Neighbourhoods of Grace, entrusted to the care of the Salvatorians. FR GREG’S LETTER “No one has greater love than to lay down his life for his friends.” DEAR FRIENDS, Mother’s Day is a special day. Each year we pause at this time to think about our mothers and those who have shaped our lives. We give thanks to God and share memories as we think about those of our mothers who have gone before us. We give thanks to God and reach out in love to our mothers who are present in our lives today. We give thanks to God and celebrate those who, like mothers, have shaped our lives. We give thanks to God and celebrate those who are mothers, or like mothers, to those that we love. It is a blessing to have either a mother or someone like Put your a mother in our lives. Mother’s Day is a time to pause, remember, give thanks to God, and share our gratitude with these special people in our life. Take some time on Psalm 42 : 5 this day to intentionally be with your family. Let them know Hopin God! that you love them and thank God for them, especially for your mother! This weekend at all the Masses in our parish we will also do this by praying for all mothers, and at the end of each Mass there will be a special blessing and gift for each mother present! This weekend after each Mass there will also be Mother’s Day cookies available in the foyer as a fundraiser for the Parish. -

Beatification Ceremony Set for Salvatorians' Founder

! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Sue Kadrich May 3, 2021 414-258-1735 BEATIFICATION CEREMONY SET FOR SALVATORIANS’ FOUNDER ‘Venerable’ Father Francis Jordan soon to be called ‘Blessed’ Milwaukee, Wis. – The Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome, Italy will be the site of the beaHficaHon of Salvatorian Founder, Venerable Father Francis Mary of the Cross Jordan. The ceremony will take place on May 15, 2021. Fr. Jordan’s path to beaHficaHon began in 1942, when documentaHon of his life and works was sent to the VaHcan for review. ATer Fr. Jordan was bestowed with the Htle “Servant of God,” Salvatorians helped spread his reputaHon of holiness with more and more people around the world. In 2011 Pope Benedict XVI officially announced that Fr. Jordan “lived a holy life,” acknowledged the “heroicity of his virtues” and declared him “Venerable.” The next steps – tesHmony and confirmaHon of a miracle – were needed before Fr. Jordan could be approved for beaHficaHon. On June 19, 2020 Pope Francis declared the authenHcity of a miracle through the intercession of Fr. Jordan. The Miracle In 2014, medical specialists informed a young couple in Brazil that their unborn child had an incurable bone disease, skeletal dysplasia. The couple, who were Lay Salvatorians, invited fellow Salvatorian Family members to pray with them through the intercession of Fr. Francis Jordan. On September 8, 2014 – Feast of the Birth of the Blessed Mother and anniversary of Fr. Jordan’s death – their daughter was born completely healthy. ATer verifying all canonical requirements, Pope Francis declared a miraculous healing worked by God through Fr. -

USA Province Necrology

© 2022 – Society of the Divine Savior – USA Province – 18th EDITION “On Whose Shoulders We Stand – the Necrology of the USA Province” ALPHABETICAL INDEX OF DECEASED MEMBERS Name Date of Death Armstrong, Br. George August 6, 2019 Bauer, Br. Paul July 21, 2019 Bauer, Br. Titian December 24, 1958 Becker, Br. Camillus April 23, 1999 Behr, Fr. Ignatius March 7, 1981 Benz, Fr. Basil July 28, 1947 Beresford, Br. Gilbert February 1, 1993 Berger, Br. Alexius December 11, 1945 Bethan, Fr. Ignatius March 10, 1928 Bielawa, Fr. Thomas May 22, 2019 Bigley, Fr. Michael January 30, 2013 Birringer, Fr. Raphael March 8, 2009 Blais, Fr. Jean October 12, 2002 Blais, Br. Venard June 24, 1965 Brady, Fr. Columban October 26, 1973 Brennan, Fr. Gilbert June 9, 1988 Brennan, Fr. Keith September 9, 2021 Brentrup, Fr. Bruce February 8, 2011 Bretl, Fr. James October 6, 2010 Brick, Fr. Paul March 15, 2013 Brochtrup, Fr. Eugene January 10, 1997 Broeg, Br. Robert May 25, 2018 Brugger, Fr. Dorotheus November 3, 1955 Bruns, Novice Urban February 23, 1951 Brusky, Fr. David February 1, 2014 Bucher, Fr. Felix April 13, 1938 Buck, Fr. Arnulf June 15, 1975 Buehler, Fr. Coloman December 23, 1959 Buff, Fr. Bardo June 2, 1991 Bunse, Br. Alphonse April 6, 1937 Cantarella, Br. Richard July 10, 2004 Carroll, Fr. Daniel September 5, 2002 Casper, Fr. Robert May 10, 1998 Christel, Fr. David January 5, 1992 Cioffi, Fr. Albert April 29, 1976 Clifford, Br. Lawrence July 3, 1980 Cooney, Fr. Denis February 9, 1973 Cotey, Bishop Arnold May 21, 1998 Cray, Fr. -

I. Men's Religious Communities, Seminaries, Houses of Study Page

I. Men’s Religious Communities, Seminaries, Houses of Study INDEX Page Religious Order Initials for Men I-2 Communities of Men, Houses of Study I-4 Seminaries I-12 Seminaries, Eastern Rite I-13 Page I-1 Updated: 10/13/2017 I. Men’s Religious Communities, Seminaries, Houses of Study Religious Order Initials for Men Religious are listed in alphabetical order by the abbreviation of the order. C.F.X. Congregation of the Brothers of St. Francis Xavier (Xaverian Brothers) C.S. Scalabrini Fathers C.S.C. Congregation of Holy Cross (Holy Cross Brothers) C.S.P. Missionary Society of St. Paul the Apostle (Paulists) C.Ss.R. Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (Redemptorists) F.C. Brothers of Charity F.S.C. Brothers of the Christian Schools (Christian Brothers) F.S.C.B. Priestly Fraternity of the Missionaries of St. Charles Borromeo* I.V.E. Institute of the Incarnate Word L.C. Legionaries of Christ M.Afr. Missionaries of Africa M.I.C. Marians of the Immaculate Conception (Marian Fathers and Brothers) M.J. Missionaries of Jesus M.M. Mary Knoll Fathers and Brothers: Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America M.S. Missionaries of Our Lady of La Salette M.S.A. Missionaries of the Holy Apostles M.S.C. Missionary Servants of Christ O.Carm. Order of Carmelites O.C.D. Order of Discalced Carmelites O.F.M. Order of Friars Minor (Franciscans) O.F.M. Cap. Order of Friars Minor, Capuchin O.F.M. Conv. Order of Friars Minor, Conventual O.F.M. Franciscan Monastery USA, Inc. -

These Twenty-Two Years

MOTHER OF THE SAVIOR SEMINARY BLACKWOOD, NEW JERSEY 101.5-1067 7hese 7wenty-7u,o Years . .. Under the patronage of Mary, the Mother of God, Mother of The Savior Seminary has grown and fulfilled its purpose of educating young men according to Christian apostolic principles, especially for the holy priesthood. We humbly ask Mary's intercession and the bless ing of the Divine Majesty upon . .. Our Priests, who devote, dedicate and consecrate themselves to the formation of Christ in those favored youths who are called from men in order to be ordained for men in the things that pertain to God ... Our Brothers, who with apostolic purpose undertake the hidden and arduous labors of Nazareth as coadjutors of the ministers of Christ . .. Our Lay Faculty, who so generously contribute their talents, time and interest to the formation of proper Christian attitudes, ideals and goals of the Seminarians . .. Our Students, who in selfless love of Jesus, the Supreme and Eternal High Priest, entrust their young minds, bodies and hearts to their educators . .. Our Friends, our Benefactors, Members of the Mater Salvatoris Guild and all those who have shared or known our apostolic dreams and labors during the past twenty-two years of service. HIS EXCELLENCY The Most Reverend Celestine J0 Damiano, SoToDo Archbishop-Bishop of Camden A Message from the Sal'vatorian Provincial ... .. FATHI::R RON :\LD BULLINGHAiII, S.D.S. A WORD OF THANKS! ONE of the greatest duties of a Christian is to give thanks. As we face a very sad event in the closing of Mother of the Savior Seminary it is this Chri.~tian spirit of thanks that pervades our minds and hearts. -

St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church

St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church 15 Glennwood Drive Rocky Mount, VA 24151 Pastoral Emergency: (202) 489-3607 Office Telephone: (540) 483-9591 Website: www.francis-of-assisi.org Office Hours: Tuesday-Friday, 9:00 am to 4:00 pm The office will be closed on Tuesday, April 3rd. March 31-April 1, 2018 Easter Sunday of the Resurrection of the Lord Pastor Marriage Preparation Fr. Mark White—[email protected] English: Fr. Mark White—[email protected] Español: Cristino Cortes & Carolina Velasco (276-734-5430) Assistant to the Pastor Kayla Acosta—[email protected] New Evangelization Maureen Shanahan, Coordinator—[email protected] Bookkeeper Pat Prillaman—[email protected] Quinceañera Coordinator Elia [email protected] (540-493-7032) Music & Liturgy Coordinator Ginny Coffman—[email protected] Website/Facebook Group/Parish IT Pat Siler—[email protected] Religious Education Linda Siler, Coordinator—[email protected] Parish Registration—Contact the Parish Office RE Classes: Sundays 9:00 am Sept.-May RE Office Hours: Sat. 12:00-4:00 pm, Sun. 8:00-11:00 am Parish Facebook Group https://www.facebook.com/groups/112238392199573/ RCIA English: David & Susan King—[email protected] Knights of Columbus Facebook Group Español: Laura Hernandez—540-278-9274 https://www.facebook.com/kofcrockymountva/ Baptism Preparation Youth Group Facebook Group English: Linda Siler—[email protected] https://www.facebook.com/groups/168563686553669/ Español—Elizabeth Ramirez (540-420-1077) Emma Arellano (714-328-5635) Pastoral Council: Lynore Arrington, Gilberto Ayala, Gloria Clifft, Albert Galvan (co-chair), Martha Graf, David King, Manuel Ortiz, Dan Shanahan (co-chair), Jack Shanahan (youth).