Roosting Patterns of the Laughing Kookaburra Dacelo Novaeguineae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

AUSTRALIA Queensland & Top End June 22 – July 4, 2013

Sunrise Birding LLC AUSTRALIA Queensland & Top End June 22 – July 4, 2013 TRIP REPORT Sunrise Birding LLC, PO Box 274, Cos Cob, CT 06807 USA www.sunrisebirding.com 203.453.6724 Sunrise Birding LLC www.sunrisebirding.com AUSTRALIA Queensland & Top End TRIP REPORT June 22 – July 4, 2013 Leaders: Gina Nichol, Steve Bird & Barry Davies HIGHLIGHTS : BIRDS MAMMALS • Rainbow Pitta • Duck-billed Platypus • Gouldian Finch • Sugar Gliders • Hooded Parrot • Striped Possum • Golden Bowerbird • Dingo • Australian Bustard • Small-eared Rock Wallaby • Papuan Frogmouth • Tawny Frogmouth MOMENTS & EXPERIENCES • Chowchilla • Thousands of Brown Noddies and • Spotted Harrier Sooty Terns at Michaelmas Cay • Chestnut-quilled Rock Pigeon • Tawny Frogmouths too close to • Pied Heron believe • Black-necked Stork • Tens of thousands of ducks and • Black-breasted Buzzard geese at Hasties Swamp • Beach Stone Curlew • The Chowchilla dawn chorus • Northern Rosella • Wompoo Fruit Dove on a nest • Double-eyed Fig Parrot • Golden Bowerbird male preening • Lovely Fairywren above our heads! • White-lined Honeyeater • Spotted Harrier flying along with • Fernwren the bus at close range • Arafura Fantail • Victoria's Riflebird displaying • Barking Owl • Aboriginal Art at Kakadu • Victoria's Riflebird Rarities • Cotton Pygmy Goose at Catana Wetland • Freckled Duck at Hastie’s Swamp • Masked Booby at Michaelmas Cay Day 1, June 22 – Cairns area Paul, Darryl, Gina and Steve arrived on the previous day and this morning before breakfast, we walked from our hotel to the Cairns Esplanade before breakfast. Just outside the hotel were male and female Brown Sunrise Birding LLC, PO Box 274, Cos Cob, CT 06807 USA www.sunrisebirding.com 203.453.6724 Honeyeaters and flocks of Rainbow Lorikeets flying over as we crossed the streets heading toward the waterfront. -

LAUGHING KOOKABURRA CORACIIFORMES Family: Alcedinidae Genus: Dacelo Species: Novaeguineae

LAUGHING KOOKABURRA CORACIIFORMES Family: Alcedinidae Genus: Dacelo Species: novaeguineae Range: native to eastern Australia; introduced to southwest Australia and Tasmania Habitat: Woods, temperate forest, scrub, often far from water Niche: Arboreal, carnivorous, diurnal Wild diet: Lizards, snakes up to 50 cm in length, crabs, large insects and small rodents Zoo diet: Life Span: (Wild) 15 years (Captivity) 20 years Sexual dimorphism: F slightly larger than M. and have less blue to rump than the M. Location in SF Zoo: Behind California Conservation Corridor APPEARANCE & PHYSICAL ADAPTATIONS: This largest of kingfishers has dark upper plumage and white under parts. Wings are spotted with white while the tail is reddish with black bands. There is a dark band passing through the eye along the sides of the head. The large bill is broad and flattened with a dark upper mandible and a lighter lower mandible. The 3-4 inch bill is hooked at the tip. They have short legs, a stout body and feet Weight: 6.9-16.4 oz that are flat with the middle and outer toes fused together (syndactyl). Length: 16 - 18 inches They will reduce their basal metabolic rate significantly at night to conserve energy. The birds display huddle behavior while roosting to stay warm as they roost communally at night. STATUS & CONSERVATION They are subject to habitat destruction and fragmentation as they need forest areas for finding food and nesting. They are listed on the IUCN Red List as Least Concern as it has an extremely large range. COMMUNICATION AND OTHER BEHAVIOR Their territorial call is a loud chorus of screams and chuckles hence the name “Laughing Jackass”. -

2019-Repeated Evolution of Drag Reduction

Repeated evolution of drag reduction at the air-water interface in diving ANGOR UNIVERSITY kingfishers Crandell, K. E.; Howe, R. O.; Falkingham, P.L. Journal of the Royal Society: Interface DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2019.0125 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 31/05/2019 Peer reviewed version Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Crandell, K. E., Howe, R. O., & Falkingham, P. L. (2019). Repeated evolution of drag reduction at the air-water interface in diving kingfishers. Journal of the Royal Society: Interface, 16, [20190125]. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2019.0125 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 01. Oct. 2021 Under review for J. R. Soc. Interface Repeated evolution of drag reduction at the -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Southern Highlands Birdwatching Areas

C Box Vale Track A walking track that follows the route of a historic railway line built in 1888 through woodland above Nattai Gorge. Access The parking area is 3.7km west of Mittagong. Follow the Old Hume Highway and turn right into Box Vale Road 100m past the bridge SOUTHERN over the F5. Amenities Picnic area. HIGHLANDS Southern Highlands Walks A variety of walking tracks, including the 9km return Box Vale BIRDWATCHERS Track. The short detour near the start to a reservoir is worthwhile. Birdwatching Areas Birds Musk Duck, Australasian Grebe, Wonga Pigeon, Glossy Black- Cockatoo, Crimson Rosella, Rockwarbler, Red Wattlebird, Golden Whistler, Rufous Whistler, Grey Fantail, Bassian Thrush. More than 250 species of birds can be seen in the Southern Highlands, a 90-minute drive south of Sydney. Some are seasonal visitors, others are D Wingecarribee River, Berrima permanent residents. Flowing through the historic town of Berrima, the Wingecarribee River is a good spot to observe Yellow-faced Honeyeaters as they This brochure highlights some of the best places head north in mid-April. Platypuses may be seen. Access Park in the centre of Berrima. to see them. The locations are easily accessible and Amenities Cafes, picnic areas, toilets. include a variety of habitats. The birds listed are Walks A good birdwatching walk can be accessed by turning right along the river from the picnic area at the end of Oxley Street and just a few of the species likely to be present. following the easy track towards the scout hut. Alternatively, the easy Stone Quarry walk follows the river to the east of the town. -

OF the TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS the Beautiful Lake Ross Stores Over 200,000 Megalitres of Water and Supplies up to 80% of Townsville’S Drinking Water

BIRDS OF THE TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS The beautiful Lake Ross stores over 200,000 megalitres of water and supplies up to 80% of Townsville’s drinking water. The Ross River Dam wall stretches 8.3km across the Ross River floodplain, providing additional flood mitigation benefit to downstream communities. The Dam’s extensive shallow margins and fringing woodlands provide habitat for over 200 species of birds. At times, the number of Australian Pelicans, Black Swans, Eurasian Coots and Hardhead ducks can run into the thousands – a magic sight to behold. The Dam is also the breeding area for the White-bellied Sea-Eagle and the Osprey. The park around the Dam and the base of the spillway are ideal habitat for bush birds. The borrow pits across the road from the dam also support a wide variety of water birds for some months after each wet season. Lake Ross and the borrow pits are located at the end of Riverway Drive, about 14km past Thuringowa Central. Birds likely to be seen include: Australasian Darter, Little Pied Cormorant, Australian Pelican, White-faced Heron, Little Egret, Eastern Great Egret, Intermediate Egret, Australian White Ibis, Royal Spoonbill, Black Kite, White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Australian Bustard, Rainbow Lorikeet, Pale-headed Rosella, Blue-winged Kookaburra, Rainbow Bee-eater, Helmeted Friarbird, Yellow Honeyeater, Brown Honeyeater, Spangled Drongo, White-bellied Cuckoo-shrike, Pied Butcherbird, Great Bowerbird, Nutmeg Mannikin, Olive-backed Sunbird. White-faced Heron ROSS RIVER The Ross River winds its way through Townsville from Ross Dam to the mouth of the river near the Townsville Port. -

Eubenangee Swamp National Park Supplement

BUSH BLITZ SPECIES DISCOVERY PROGRAM Eubenangee Swamp National Park Supplement Australian Biological Resources Study Contents Key Appendix A: Species Lists 3 ¤ = Previously recorded on the reserve and Fauna 4 found on this survey * = New record for this reserve Vertebrates 4 ^ = Exotic/Pest Mammals 4 # = EPBC listed Birds 4 ~ = NCA listed Frogs and Toads 10 EPBC = Environment Protection and Biodiversity Reptiles 10 Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) Invertebrates 11 NCA = Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Queensland) Butterflies 11 Beetles 11 Colour coding for entries: Dragonflies and Damselflies 11 Black = Previously recorded on the reserve and found on this survey Snails and Slugs 11 Brown = Putative new species Flora 12 Blue = Previously recorded on the reserve but Flowering Plants 12 not found on this survey Ferns 14 Appendix B: Threatened Species 15 Fauna 16 Vertebrates 16 Birds 16 Reptiles 16 Flora 16 Flowering Plants 16 Appendix C: Exotic and Pest Species 17 Flora 18 Flowering Plants 18 2 Bush Blitz survey report — Far North QLD 2010 Appendix A: Species Lists Nomenclature and taxonomy used in this appendix are consistent with that from the Australian Faunal Directory (AFD), the Australian Plant Name Index (APNI) and the Australian Plant Census (APC). Current at March 2013 Eubenangee Swamp National Park Supplement 3 Fauna Vertebrates Mammals Family Species Common name Muridae Melomys burtoni * Grassland Melomys Peramelidae Isoodon macrourus Northern Brown Bandicoot Birds Family Species Common name Acanthizidae Gerygone levigaster -

Newsletter Autumn Is Here and the Migratory Birds Are on Their Way to Warmer Climes

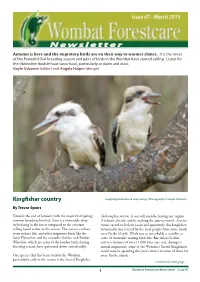

Issue 47 - March 2019 Newsletter Autumn is here and the migratory birds are on their way to warmer climes. It is the onset of the Powerful Owl breeding season and pairs of birds in the Wombat have started calling. Listen for the distinctive double hoot (woo-hoo), particularly at dawn and dusk. Gayle Osborne (editor) and Angela Halpin (design) Kingfisher country Laughing Kookaburra and young. Photography © Gayle Osborne By Trevor Speirs Towards the end of January, with the majority of spring/ Todiramphus sanctus. It too will soon be leaving our region, summer breeding finished, there is a noticeable drop if it hasn’t already, and be making the journey north. Sanctus in birdsong in the forest compared to the constant means sacred or holy in Latin and apparently this kingfisher, calling heard earlier in the season. The various cuckoos historically, was revered by the local people from some South- seem to have left, and other migratory birds like the west Pacific Islands. While not as remarkable a traveller as Satin Flycatcher and the nomadic Golden and Rufous some of Australia’s wading birds (the Bar-tailed Godwit Whistlers, which are some of the loudest birds during covers a distance of over 11,000 kms, one way, during its breeding season, have quietened down considerably. annual migration), some of the Wombat’s Sacred Kingfishers could soon be spending this year’s winter in some of those far One species that has been vocal in the Wombat, away Pacific islands. particularly early in the season is the Sacred Kingfisher continued next page .. -

The Rainbow Bird

The Rainbow Bird Volume 6 Number 1 February 2017 (Issue 89) In this Issue Symbiosis Page 2 Willie Wagtails Page 5 The Sad Death of a Page 6 Kingfisher My Bird Page 8 White-eared Page 9 Honeyeaters Who is Robert Hall? Page 10 Black and White Birds Page 12 Challenge Count 2016 Page 13 Glossy Ibis Page 14 Grey Teal Page 15 Striated Pardalotes Page 16 Sparrowhawks Page 17 Wind beneath their Page 18 Wings Young Spoonbills Page 19 Species Profile Page 20 Hotspot Profile Page 23 1 The Challenge Page 25 Sightings and Calendar Page 26 The Rainbow Bird Photo acknowledgements for title page: Symbiosis Allan Taylor, Lindsay Cupper, Ken Job, Pauline I was recently handed a copy of the Sunraysia Naturalists’ Follett, Richard Wells, Research Trusts’ 1975/76 report by Helen. This will be kept in Finley Japp. the cabinet that holds the books of the Favaloro collection. The report covers a year which seems to be one of the best for sighting birds in recent memory. Part of the report details the Trust members’ observations on the bird nests in the Tapio area just north of Hollands Lake. There were large numbers of White-browed Woodswallow and Masked Woodswallow nests constructed close to each other and to those of Black-faced Cuckoo-Shrikes. Apparently, this behaviour is well-known but I don’t know the reason for it. The article got me thinking about Symbiotic Relationships. When referring to relationships between flora and fauna, it is common to sub-divide these relationships into Mutualistic; Commensalistic; and Parasitic relationships. -

Body Temperature and Activity Patterns of Free-Living Laughing Kookaburras: the Largest Kingfisher Is Heterothermic

The Condor 0(0):1–6 c The Cooper Ornithological Society 2008 BODY TEMPERATURE AND ACTIVITY PATTERNS OF FREE-LIVING LAUGHING KOOKABURRAS: THE LARGEST KINGFISHER IS HETEROTHERMIC , , , CHRISTINE E. COOPER1 2 4,GERHARD KORTNER2,MARK BRIGHAM2 3, AND FRITZ GEISER2 1Environmental Biology, Curtin University of Technology, PO Box U1987, Perth, Western Australia, Australia 2Centre for Behavioural and Physiological Ecology, Zoology, University of New England, Armidale, N.S.W., Australia 3Department of Biology, University of Regina, Regina, SK S4S 0A2, Canada Abstract. We show that free-ranging Laughing Kookaburras (Dacelo novaeguineae), the largest kingfishers, ◦ are heterothermic. Their minimum recorded body temperature (Tb) was 28.6 C, and the maximum daily Tb range was 9.1◦C, which makes kookaburras only the second coraciiform species and the only member of the Alcedinidae known to be heterothermic. The amplitude of nocturnal body temperature variation for wild, free- living kookaburras during winter was substantially greater than the mean of 2.6◦C measured previously for captive kookaburras. Calculated metabolic savings from nocturnal heterothermia were up to 5.6 ± 0.9 kJ per night. There was little effect of ambient temperature on any of the calculated Tb-dependent variables for the kookaburras, although ambient temperature did influence the time that activity commenced for these diurnal birds. Kookaburras used endogenous metabolic heat production to rewarm from low Tb, rather than relying on passive rewarming. Rewarming rates (0.05 ± 0.01◦Cmin−1) were consistent with those of other avian species. Captivity can have major effects on thermoregulation for birds, and therefore the importance of field studies of wild, free-living individuals is paramount for understanding the biology of avian temperature regulation. -

RCP Have Been Created, Except Two 'Phase In'

CORACIIFORMES TAG REGIONAL COLLECTION PLAN Third Edition, December 31, 2008 White-throated Bee-eaters D. Shapiro, copyright Wildlife Conservation Society Prepared by the Coraciiformes Taxon Advisory Group Edited by Christine Sheppard TAG website address: http://www.coraciiformestag.com/ Table of Contents Page Coraciiformes TAG steering committee 3 TAG Advisors 4 Coraciiformes TAG definition and taxonomy 7 Species in the order Coraciiformes 8 Coraciiformes TAG Mission Statement and goals 13 Space issues 14 North American and Global ISIS population data for species in the Coraciiformes 15 Criteria Used in Evaluation of Taxa 20 Program definitions 21 Decision Tree 22 Decision tree diagrammed 24 Program designation assessment details for Coraciiformes taxa 25 Coraciiformes TAG programs and program status 27 Coraciiformes TAG programs, program functions and PMC advisors 28 Program narratives 29 References 36 CORACIIFORMES TAG STEERING COMMITTEE The Coraciiformes TAG has nine members, elected for staggered three year terms (excepting the chair). Chair: Christine Sheppard Curator, Ornithology, Wildlife Conservation Society/Bronx Zoo 2300 Southern Blvd. Bronx, NY 10460 Phone: 718 220-6882 Fax 718 733 7300 email: [email protected] Vice Chair: Lee Schoen, studbookkeeper Great and Rhino Hornbills Curator of Birds Audubon Zoo PO Box 4327 New Orleans, LA 70118 Phone: 504 861 5124 Fax: 504 866 0819 email: [email protected] Secretary: (non-voting) Kevin Graham , PMP coordinator, Blue-crowned Motmot Department of Ornithology Disney's Animal Kingdom PO Box 10000 Lake Buena Vista, FL 32830 Phone: (407) 938-2501 Fax: 407 939 6240 email: [email protected] John Azua Curator, Ornithology, Denver Zoological Gardens 2300 Steele St.