Report Into the Law and Procedures in Serious Sexual Offences in Northern Ireland Part 1 Sir John Gillen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Full Text In

The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS Future Academy ISSN: 2357-1330 https://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.03.40 UUMILC 2017 9TH UUM INTERNATIONAL LEGAL CONFERENCE THE ONLINE SOCIAL NETWORK ERA: ARE THE CHILDREN PROTECTED IN MALAYSIA? Zainal Amin Ayub (a)*, Zuryati Mohamed Yusoff (b) *Corresponding author (a) School of Law, College of Law, Government & International Studies, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia, [email protected], +604 928 8073 (b) School of Law, College of Law, Government & International Studies, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia, [email protected], +604 928 8089 Abstract The phenomenon of online social networking during the age of the web creates an era known as the ‘Online Social Network Era’. Whilst the advantages of the online social network are numerous, the drawbacks of online social network are also worrying. The explosion of the use of online social networks creates avenues for cybercriminals to commit crimes online, due to the rise of information technology and Internet use, which results in the growth of the Internet society which includes the children. The children, who are in need of ‘extra’ protection, are among the community in the online social network, and they are exposed to the cybercrimes which may be committed against them. This article seeks to explore and analyse the position on the protection of the children in the online society; and the focus is in Malaysia while other jurisdictions are referred as source of critique. The position in Malaysia is looked into before the introduction of the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017. -

Sexual Offences

Sexual Offences Definitive Guideline GUIDELINE DEFINITIVE Contents Applicability of guideline 7 Rape and assault offences 9 Rape 9 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 1) Assault by penetration 13 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 2) Sexual assault 17 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 3) Causing a person to engage in sexual activity without consent 21 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 4) Offences where the victim is a child 27 Rape of a child under 13 27 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 5) Assault of a child under 13 by penetration 33 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 6) Sexual assault of a child under 13 37 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 7) Causing or inciting a child under 13 to engage in sexual activity 41 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 8) Sexual activity with a child 45 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 9) Causing or inciting a child to engage in sexual activity 45 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 10) Sexual activity with a child family member 51 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 25) Inciting a child family member to engage in sexual activity 51 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 26) Engaging in sexual activity in the presence of a child 57 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 11) Effective from 1 April 2014 2 Sexual Offences Definitive Guideline Causing a child to watch a sexual act 57 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 12) Arranging or facilitating the commission of a child sex offence 61 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 14) Meeting a child following sexual grooming 63 Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 15) Abuse of position of trust: -

1 Child Pornography Alisdair A. Gillespie.* It Would Seem, At

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lancaster E-Prints Child Pornography Alisdair A. Gillespie.* It would seem, at one level, to be somewhat gratuitous to include an article on child pornography in a special issue on ‘Dangerous Speech’. Child pornography would seem to obviously meet the criteria of dangerous speech, with no real discussion required. However, as will be seen in this article, this is not necessarily the case. There remain a number of controversial issues that potentially raise both under-criminalisation and over-criminalisation. This article seeks to critique the current law of child pornography using doctrinal methods, to assess its impact and reach. It will do this by breaking down the definition of child pornography into its constituent parts, identifying how the law has constructed these elements and whether they contribute to an effective legislative response to tackling the sexual exploitation of children through sexual images. The article concludes that there are some areas that require adjustment and puts forward the case for limited legislative changes to ensure that exploitative pictures are criminalised but in such a way that innocent pictures are not. DEFINING CHILD PORNOGRAPHY There is no single definition of ‘child pornography’ and indeed the term itself remains controversial.1 In order to understand the interaction between child pornography and dangerous speech, it is necessary to consider the definition of child pornography. The difficulty with this is that there are hundreds of different definitions available. Even international law cannot agree, with different definitions being used in the Optional Protocol to the CRC on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography2 (hereafter ‘OPSC’) and the Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse3 (hereafter ‘Lanzarote Convention’4). -

Issues Paper on Cyber-Crime Affecting Personal Safety, Privacy and Reputation Including Cyber-Bullying (LRC IP 6-2014)

Issues Paper on Cyber-crime affecting personal safety, privacy and reputation including cyber-bullying (LRC IP 6-2014) BACKGROUND TO THIS ISSUES PAPER AND THE QUESTIONS RAISED This Issues Paper forms part of the Commission’s Fourth Programme of Law Reform,1 which includes a project to review the law on cyber-crime affecting personal safety, privacy and reputation including cyber-bullying. The criminal law is important in this area, particularly as a deterrent, but civil remedies, including “take-down” orders, are also significant because victims of cyber-harassment need fast remedies once material has been posted online.2 The Commission seeks the views of interested parties on the following 5 issues. 1. Whether the harassment offence in section 10 of the Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person Act 1997 should be amended to incorporate a specific reference to cyber-harassment, including indirect cyber-harassment (the questions for which are on page 13); 2. Whether there should be an offence that involves a single serious interference, through cyber technology, with another person’s privacy (the questions for which are on page 23); 3. Whether current law on hate crime adequately addresses activity that uses cyber technology and social media (the questions for which are on page 26); 4. Whether current penalties for offences which can apply to cyber-harassment and related behaviour are adequate (the questions for which are on page 28); 5. The adequacy of civil law remedies to protect against cyber-harassment and to safeguard the right to privacy (the questions for which are on page 35); Cyber-harassment and other harmful cyber communications The emergence of cyber technology has transformed how we communicate with others. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 516 12 October 2010 No. 50 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 12 October 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 135 12 OCTOBER 2010 136 taking on more tax officers and ensuring a good House of Commons geographical spread to make sure we get in the maximum tax revenues possible? Tuesday 12 October 2010 Mr Gauke: As was made clear in the Chief Secretary to the Treasury’s statement, the Government are determined The House met at half-past Two o’clock to reduce the tax gap. It currently stands at £42 billion. It is too high, but we are determined to take measures to PRAYERS address it and we have already announced proposals by which we can reduce the tax gap. [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Budget (Regional Differences) BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS 2. Kevin Brennan (Cardiff West) (Lab): What representations he has received on variations between ELECTORAL COMMISSION the English regions and constituent parts of the UK in respect of the effects of the measures in the June 2010 The VICE-CHAMBERLAIN OF THE HOUSEHOLD reported to the House, That the Address of 15th September, Budget. [16481] praying that Her Majesty will appoint as Electoral Commissioners: 3. Paul Blomfield (Sheffield Central) (Lab): What representations he has received on variations between (1) Angela Frances, Baroness Browning, with effect the English regions and constituent parts of the UK in from 1 October 2010 for the period ending on 30 September respect of the effects of the measures in the June 2010 2014; Budget. -

Part 1 the Receipt of Evidence by Queensland Courts: the Evidence

To: Foreword To: Table of Contents THE RECEIPT OF EVIDENCE BY QUEENSLAND COURTS: THE EVIDENCE OF CHILDREN Report No 55 Part 1 Queensland Law Reform Commission June 2000 The short citation for this Report is QLRC R 55 Part 1. Published by the Queensland Law Reform Commission, June 2000. Copyright is retained by the Queensland Law Reform Commission. ISBN: 0 7242 7738 2 Printed by: THE RECEIPT OF EVIDENCE BY QUEENSLAND COURTS: THE EVIDENCE OF CHILDREN Report No 55 Part 1 Queensland Law Reform Commission June 2000 To: The Honourable Matt Foley MLA Attorney-General, Minister for Justice and Minister for the Arts In accordance with section 15 of the Law Reform Commission Act 1968, the Commission is pleased to present Part 1 of its Report on The Evidence of Children. The Honourable Mr Justice J D M Muir The Honourable Justice D A Mullins Chairman Member Mr W G Briscoe Professor W D Duncan Member Member Mr P J MacFarlane Mr P D McMurdo QC Member Member Ms S C Sheridan Member COMMISSIONERS Chairman: The Hon Mr Justice J D M Muir Members: The Hon Justice D A Mullins Mr W G Briscoe Professor W D Duncan Mr P J MacFarlane Mr P D McMurdo QC Ms S C Sheridan SECRETARIAT Director: Ms P A Cooper Acting Secretary: Ms V Mostina Senior Research Officer: Ms C E Riethmuller Legal Officers: Ms K Schultz Ms C M Treloar Administrative Officers: Ms T L Bastiani Mrs L J Kerr The Commission’s premises are located on the 7th Floor, 50 Ann Street, Brisbane. -

Rights of Women from Report to Court a Handbook for Adult Survivors of Sexual Violence Rights of Women Aims to Achieve Equality, Justice and Respect for All Women

Rights of Women From Report to Court A handbook for adult survivors of sexual violence Rights of Women aims to achieve equality, justice and respect for all women. Rights of Women advises, educates and empowers women by: ● Providing women with free, confidential legal advice by specialist women solicitors and barristers. ● Enabling women to understand and benefit from their legal rights through accessible and timely publications and training. ● Campaigning to ensure that women’s voices are heard and law and policy meets all women’s needs. ISBN 10: 0-9510879-6-7 ISBN 13: 978-0-9510879-6-1 Rights of Women, 52-54 Featherstone Street, London EC1Y 8RT For advice on family law, domestic violence and relationship breakdown telephone 020 7251 6577 (lines open Tuesday to Thursday 2-4pm and 7-9pm, Friday 12-2pm). For advice about sexual violence, immigration or asylum law telephone 020 7251 8887 (lines open Monday 11am-1pm and Tuesday 10am-12noon). Alternative formats of this book are available on request. Please contact us for further information. Admin line: 020 7251 6575/6 Textphone: 020 7490 2562 Fax: 020 7490 5377 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rightsofwomen.org.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of Rights of Women. To receive further copies of this publication, please contact Rights of Women. Disclaimer: The guide provides a basic overview of complex terminology, rights, laws, processes and procedures for England and Wales (other areas such as Scotland have different laws and processes). -

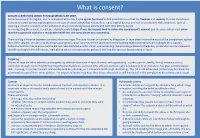

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he/she did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical disabilities, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Criminal Procedure

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. '! • .,~,..,-....... ~:, ',";"y -- -"~-.:,':'~: ~·~~,r~·'·; -~ .. -~.-- " "'. ..,...;;. ~"~ .' .. , : ..:.. .. ~-'" --~,. ~~"?:'« ""~: : -'.:' - . ~F~~~·:=<~_;,."r. .'~~. <t-···;<~c- .",., . ~""!." " '. ;.... ..... .-" - .~- . ": . OUTLINE Of FIRST ISSUES PAPER CRIMINAL PROCEDURE ITRODUCTION :75 IN COURTS :SSI(JNS 130l/Cj3 NEW SOUTH WALES LAW REFORM COMMISSION OUTLINE OF FIRST ISSUES PAPER CRIMINA\L PROCEDURE GENERAL INTRODUCTION AND PROCEEDINGS IN COURTS OF PETTY SESSIONS 1982 17697H-l -ii- New South Wales Law Reform Commission The Law Reform Commission is constituted by the Law Reform Commission Act, 1967. The Commissioners are: Chairman: Professor Ronald Sackville Deputy Chairman: Mr. Russell Scott Full-time Mr. Denis Gressier Commissioners: Mr. J.R T. Wood, Q.c. Part-time Mr. I.McC. Barker, Q.C. Commissioners: Mrs. B, Cass Mr. J.H.P. Disney The Hon. Mr. Justice P.E. Nygh The Hon. Mr. Justice Adrian Roden The Han. Mr. Justice Andrew Rogers Ms. P. Smith Mr. H.D. Sperling, Q.C. Research Director: Ms. Marcia Neave Members of the research staff are: Mr. Paul Garde (until 29 November 1982) Ms. Ruth Jones Ms. Philippa McDonald Ms. Helen Mills Ms. Fiona Tito The Secretary of the Commission is Mr. Bruce Buchanan and its offices are at 16th Level, Goodsell Building, 8-12 Chifley Square, Sydney, N.S.W. 2000. U.S. Department of Justice National Institute 01 Justice This document has been reproduced exaclly as received from the person or organization originating it Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Monday Volume 507 15 March 2010 No. 57 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 15 March 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 589 15 MARCH 2010 590 to pay less to have one of these placements instead of House of Commons paying the minimum wage, which has been so hard fought for? Monday 15 March 2010 Jonathan Shaw: The hon. Gentleman is right to remind the House of the minimum wage, which was introduced The House met at half-past Two o’clock by the Labour Government and resisted in many quarters; I am pleased to say that there is now some consensus. We will ensure with contractors—our providers who PRAYERS ensure that we get places for people who have been out of work for two years, beginning with the pilot areas of Greater Manchester, Cambridge, Norfolk and Suffolk—that [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] there is no displacement. This is about work experience. For people who have been out of work, that is an important part of their being able to get back to work. BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS We think that if people are given that opportunity, they should take it. DEATH OF A MEMBER Jobseeker’s Allowance (North Wiltshire) Mr. Speaker: I regret to have to report to the House the death of Dr. -

A Guide to the Criminal Justice System in Northern Ireland

a guide to the criminal justice system in Northern Ireland This Guide to the Criminal Justice System in Northern Ireland has been designed to explain each aspect of the system, and the roles and responsibilities of those working within it. The Criminal Justice System Northern Ireland (CJSNI) It should guide you through the system from is made up of 7 main statutory agencies: beginning to end, providing information for a Northern Ireland Court Service NICtS Northern Ireland Office NIO variety of users of the system. Northern Ireland Prison Service NIPS Police Service of Northern Ireland PSNI Probation Board for Northern Ireland PBNI Public Prosecution Service PPS Youth Justice Agency YJA The CJSNI is responsible for investigating crimes, fi nding the people who have committed them, and bringing them to justice. It also works to help the victims of crime, and to rehabilitate offenders after their punishment. The purpose of the CJSNI is: to support the administration of justice, to promote confi dence in the criminal justice system, and to contribute to the reduction of crime and the fear of crime. The CJSNI aims to - provide a fair and effective criminal justice system for the community; - work together to help reduce crime and the fear of crime; - make the criminal justice system as open, inclusive and accessible as possible,and promote confi dence in the administration of justice; and - improve service delivery by enhancing the levels of effectiveness, effi ciency and co-operation within the system. As well as tackling crime and the fear of crime, the CJSNI also has responsibility for ensuring that criminal law is kept up to date. -

Spooky Business: Corporate Espionage Against Nonprofit Organizations

Spooky Business: Corporate Espionage Against Nonprofit Organizations By Gary Ruskin Essential Information P.O Box 19405 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 387-8030 November 20, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 5 The brave new world of corporate espionage 5 The rise of corporate espionage against nonprofit organizations 6 NARRATIVES OF CORPORATE ESPIONAGE 9 Beckett Brown International vs. many nonprofit groups 9 The Center for Food Safety, Friends of the Earth and GE Food Alert 13 U.S. Public Interest Research Group, Friends of the Earth, National Environmental Trust/GE Food Alert, Center for Food Safety, Environmental Media Services, Environmental Working Group, Institute for Global Communications, Pesticide Action Network. 15 Fenton Communications 15 Greenpeace, CLEAN and the Lake Charles Project 16 North Valley Coalition 17 Nursing home activists 17 Mary Lou Sapone and the Brady Campaign 17 US Chamber of Commerce/HBGary Federal/Hunton & Williams vs. U.S. Chamber Watch/Public Citizen/Public Campaign/MoveOn.org/Velvet Revolution/Center for American Progress/Tides Foundation/Justice Through Music/Move to Amend/Ruckus Society 18 HBGary Federal/Hunton & Williams/Bank of America vs. WikiLeaks 21 Chevron/Kroll in Ecuador 22 Walmart vs. Up Against the Wal 23 Électricité de France vs. Greenpeace 23 E.ON/Scottish Resources Group/Scottish Power/Vericola/Rebecca Todd vs. the Camp for Climate Action 25 Burger King and Diplomatic Tactical Services vs. the Coalition of Immokalee Workers 26 The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association and others vs. James Love/Knowledge Ecology International 26 Feld Entertainment vs. PETA, PAWS and other animal protection groups 27 BAE vs.