National Interagency Coordination Center Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northeastern California Ethanol Manufacturing Feasibility Study

Northeastern California Ethanol Manufacturing Feasibility Study Prepared by: Quincy Library Group California Energy Commission -f California Institute of Food and Agricultural Research Plumas Corporation TSS Consultants National Renewable Energy Laboratory November 1997 'tt NREIJTP-580-24676 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The State of California is facedwith severalcritical issues relatedto how its biomassresources are used and managed.In particular,due to suppressionof forestfires, large quantitiesof dead/diseased treesand underbrush have accumulatedin the forest,creating dangerousfuel loadingwhich threatens human life and property. Resultingfires are so intensethat they destroythe forest ecosystem.In addition,the unnaturalecosystem producedby fire suppressionis endangeringforest health. To deal with theseissues, the Quincy Library Group has put forth a plan to strategicallythin the forestsso as to reducefire danger,improve forest health, and restoreecosystem balance. However, a key questionis what will be donewith the smallertrees (both live and dead)once they are removed from the forests. This reportpresents the resultsof onepotential use of the biomass- conversion to fuel ethanol and cogenerated electricity.This option has appeal in that the technologyfor ethanol productionfrom biomass is readyfor demonstrationand the demandfor fuel oxygenates,such as ethanol and ETBE, is growing in California. In addition, thereare synergistic benefits to the existing biomass-electricity industry.Finally, the technologyis ecologicallysound. The Quincy Library -

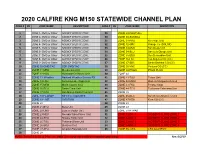

2020 Calfire Kng M150 Statewide Channel Plan Zone # Ch Zone Name Description Zone # Ch Zone Name Decription

2020 CALFIRE KNG M150 STATEWIDE CHANNEL PLAN ZONE # CH ZONE NAME DESCRIPTION ZONE # CH ZONE NAME DECRIPTION 1 ZONE 1- CMD or Other AGENCY SPECIFIC ZONE 29 ZONE 29-FOOTHILL 2 ZONE 2- CMD or Other AGENCY SPECIFIC ZONE 30 ZONE 30-SUSANA 3 ZONE 3- CMD or Other AGENCY SPECIFIC ZONE 31 ZONE 31-RRU Riverside Unit 4 ZONE 4- CMD or Other AGENCY SPECIFIC ZONE 32 ZONE 32-ORC Orange Co (SOLAR) 5 ZONE 5- CMD or Other AGENCY SPECIFIC ZONE 33 ZONE 33-MVU San Diego Unit 6 ZONE 6- CMD or Other AGENCY SPECIFIC ZONE 34 ZONE 34-SLU San Luis Obispo Unit 7 ZONE 7- CMD or Other AGENCY SPECIFIC ZONE 35 ZONE 35-BDU San Bernardino Unit 8 ZONE 8- CMD or Other AGENCY SPECIFIC ZONE 36 ZONE 36-LAC Los Angeles CO (CC) 9 ZONE 9- CMD or Other AGENCY SPECIFIC ZONE 37 ZONE 37-SBC Santa Barbara CO (CC) 10 ZONE 10-CMD/TAC CDF CMD/TAC 38 ZONE 38-VNC Ventura CO (CC) 11 ZONE 11-MEU Mendocino Unit 39 ZONE 39-PROS PROS PLAN 12 ZONE 12-HUU Humboldt-Del Norte Unit 40 ZONE 40 13 ZONE 13 Weather National Weather Service RX 41 ZONE 41-TUU Tulare Unit 14 ZONE 14-LNU Sonoma-Lake-Napa Unit 42 ZONE 42-MMU Madera-Mariposa-Merced 15 ZONE 15-MRN Marin County (CC) 43 ZONE 43-FKU Fresno Kings 16 ZONE 16-SCU Santa Clara Unit 44 ZONE 44-TCU Tuolumne-Calaveras Unit 17 ZONE 17-CZU San Mateo-Santa Cruz Unit 45 ZONE 45 18 ZONE 18-FED/IOP NIFC/Inter Op/USFS 46 ZONE 46-BEU San Benito-Monterey Unit 19 ZONE 19 - AIR AVIATION 47 ZONE 47-KRN Kern CO (CC) 20 ZONE 20 48 ZONE 48 21 ZONE 21-BTU Butte Unit 49 ZONE 49 22 ZONE 22-LMU Lassen Modoc Unit 50 ZONE 50-NTPAD 23 ZONE 23-NEU Nevada-Yuba-Placer Unit 51 ZONE 51-INC 1 INCIDENT CLONE ZONE 1 24 ZONE 24-SHU Shasta-Trinity Unit 52 ZONE 52-INC 2 INCIDENT CLONE ZONE 2 25 ZONE 25-TGU Tehama-Glenn Unit 53 ZONE 53-INC 3 INCIDENT CLONE ZONE 3 26 ZONE 26-SKU Siskiyou Unit 54 ZONE 54-INC 4 INCIDENT CLONE ZONE 4 27 ZONE 27-AEU Amador-Eldorado Unit 55 ZONE 55- CFA CFA ACADEMY 28 ZONE 28 NOTE: Zones 51,52,53, & 54 are the ONLY Zones you can modify by keypad programming. -

Bulletin 2020-11 Mandatory Moratorium on Cancellations

RICARDO LARA CALIFORNIA INSURANCE COMMISSIONER BULLETIN 2020-11 TO: All Admitted and Non-Admitted Insurers Writing Residential Property Insurance in California FROM: Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara DATE: November 5, 2020 RE: Mandatory Moratorium on Cancellations and Non-Renewals of Policies of Residential Property Insurance After the Declaration of a State of Emergency As enacted by Senate Bill 824 (Lara, Chapter 616, Statutes of 2018) Insurance Code section 675.1, subdivision (b)(1) provides: “An insurer shall not cancel or refuse to renew a policy of residential property insurance for a property located in any ZIP Code within or adjacent to the fire perimeter, for one year after the declaration of a state of emergency as defined in Section 8558 of the Government Code, based solely on the fact that the insured structure is located in an area in which a wildfire has occurred. This prohibition applies to all policies of residential property insurance in effect at the time of the declared emergency.” (Emphasis added.) Section 675.1, subdivision (d) defines “policy of residential property insurance” as follows: “…policy residential property insurance” has the meaning described in subdivision (a) of Section 10087.” (Emphasis added.) Section 10087, subdivision (a) provides: “…’policy of residential property insurance’ shall mean a policy insuring individually owned residential structures of not more than four dwelling units, individually owned condominium units, or individually owned mobilehomes, and their contents, located in this state -

Smoke Still Hurting Northern California Air Quality, but LNU Fire Isn't Main

Smoke still hurting Northern California air quality, but LNU Fire isn’t main culprit By Michael McGough Sacramento Bee, Monday, Aug. 31, 2020 The air remained unhealthy in the Sacramento area Monday morning as wildfires continue to burn across Northern California, and some of the morning relief that helped out last week is absent. Monitors from local air quality districts showed AQI readings in the “unhealthy” classification, from 151 to 200, in the early morning hours across the capital region, according to SpareTheAir.com. Pollutant levels are expected to stay in that range most of the day, with the sky already hazy and the smell of smoke apparent outdoors as of 6:30 a.m. A couple of days last week, an overnight Delta breeze helped clear some smoke away from Sacramento and kept AQI readings significantly lower until pollutants rolled in around midday. The weather hasn’t been quite as cooperative this week. The Spare The Air forecast page says that a “strong temperature inversion” combined with onshore winds Sunday increased wildfire pollutant buildup for Sacramento. Poor air quality will persist as northerly winds continue. Smoke has sullied the skies in Northern California for two weeks, ever since dozens of large fires and hundreds of smaller ones sparked during a powerful thunderstorm that brought down thousands of lightning strikes. For much of that stretch, Sacramento’s air pollution has come primarily from the LNU Lightning Complex, which as of Sunday evening had scorched more than 375,000 acres in parts of Napa, Sonoma, Solano, Yolo and Lake counties west of the capital. -

2021 California Mobilization Guide

2021 2021 California Mobilization Guide Table of Contents Chapter 10 – Objectives, Policy, Scope of Operations and Administration ....................................................1 Mission Statement ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographic Area Coordination Center ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Unit Level .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Incident Priorities ............................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Initial Attack ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Immediate Need ................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Drawdown for Initial Attack (IA) ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mobilization/ -

GACC Detailed Situation Report - by Protection

GACC Detailed Situation Report - by Protection Report Date: 09/25/2021 Geographic Area: Northern California Area Coordination Center Preparedness Level: IV 0 Wildfire Activity: Agency Unit Name Unit ID Fire P/ New New Uncntrld Human Human Lightning Lightning Total Total Acres Danger L Fires Acres Fires Fires Acres Fires Acres Fires (YTD) (YTD) (YTD) (YTD) BIA Hoopa Valley Tribe CA-HIA H 5 0 0 0 61 70 0 216 61 286 BIA 0 0 0 61 70 0 216 61 286 BLM Northern California District (CA-LNF) CA-NOD L 1 0 0 0 16 146.6 22 149.6 38 296.2 BLM 0 0 0 16 146.6 22 149.6 38 296.2 C&L Auburn Volunteer Fire Department CA-ABR N/R American Canyon Fire Protection District CA-ACY N/R Adin Fire Protection District CA-ADI N/R Anderson Fire Protection District CA-AFD N/R Alta Fire Protection District CA-AFP N/R Albion/Little River Volunteer Fire Department CA-ALR N/R Alturas City Fire Department CA-ALV N/R Annapolis Volunteer Fire Department CA-ANN N/R Arbuckle/College City Fire Protection District CA-ARB N/R Arcata Fire Protection District CA-ARF N/R Artois Fire Protection District CA-ART N/R Anderson Valley Fire Department CA-AVY N/R Bayliss Fire Protection District CA-BAY N/R Brooktrails Community Service District Fire Department CA-BCS N/R Bodega Bay Fire Protection District CA-BDB N/R Beckwourth Fire Protection District CA-BEC N/R Ben Lomond Fire Protection District CA-BEN N/R Sep 25, 2021 1 7:04:29 PM GACC Detailed Situation Report - by Protection Report Date: 09/25/2021 Geographic Area: Northern California Area Coordination Center Preparedness Level: IV -

The Knightly Times 1St Edition December, 2020

The Knightly Times 1st Edition December, 2020 Staff: Chief Editor: Simran Bhasin Editors: Jiya Kohli Yukti Malik Rachael Rakhara Reporters/Photographers: Jiya Ashar Nilani Bharathvajan Simran Bhasin Saara Dash Afsheen Fathima Evelyn Fu Sana Gupta Praveen Hariharan Mahreen Hydari Jiya Kohli Ananya Mahidhara Yukti Malik Sreehaas Mannepalli Khushee Matani Akshita Mohapatra Trisha Ojha Rachael Rakhara Deepsikha Sahu Diya Senthil Emma Shrivastava Vihaan Singh Dhriti Vohra Manas Yedia Advisors: Mrs. Coscarelli Mr. Cherence Digital Dilemma in Virtual Classroom By: Mahreen Hydari As we know, the Coronavirus pandemic started in 2019 and has stayed with us. Coronavirus is a very deadly virus and has caused a lot of death and suffering throughout the world. Coronavirus can spread by air so it is important for everyone to keep their distance from those who are not part of their family or their household. This resulted in schools closing throughout the world including New Jersey. As in-person schools closed, the classes had to go virtual. Students had to learn a new way of studying and how to deal with studying from home. The schools went virtual initially in March so the end of last year was spent from home for many teachers and students. Since no one was ready for a big change like that, it was very hard for everyone to adjust. Everyone needed to have a computer and internet at home. This is not the case for every student so it may have taken a while for everyone to get going. Once students were able to get online, they had to learn a new learning platform which was different from anything they may have been used to. -

Unit Identifier Guide: Data Report

A Publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Unit Identifier Guide: Data Report PMS 931 - Published Date: Wednesday, June 17, 2020 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Data Management Committee. Prepared and maintained by the Unit Identifier Unit. Questions regarding the content of this product should be directed to the NWCG Unit Identifier Unit (UIU), National Interagency Fire Center, 3833 S Development Avenue, Boise ID 83705, or to the UIU members listed on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: none. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group”, “NWCG”, and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report 2020

National Interagency Coordination Center Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report 2020 Cameron Peak Fire, Colorado Table of Contents Identifier Legend page…………..2 Preface page…………..3 Fire Environment Summary page…………..4 National Fire Activity Synopsis page…………..7 Significant Wildfires page…………..10 Wildfires and Acres page ………….12 National Preparedness Levels page…………..19 International Resource Mobilizations page…………..20 Type 1 and 2 Incident Management Teams page…………..20 Department of Defense page…………..23 Crews page…………..24 Engines page…………..26 Overhead page…………..29 Helicopters page…………..30 Fixed Wing Aircraft page…………..32 Equipment Services (Caterers and Showers) page…………..38 Radio and Weather Equipment page…………..40 Wildland Fires and Acres by State and Agency page…………..41 Benchmarks (Records) page…………..52 Acronyms and Terminology page…………..53 1 Identifier Legend Interagency Coordination Centers Government Agencies NICC – National Interagency Coordination Center NIFC – National Interagency Fire Center Department of the Interior: AK - Alaska BIA - Bureau of Indian Affairs EA - Eastern Area BLM - Bureau of Land Management GB - Great Basin FWS - Fish & Wildlife Service NO - Northern California NPS - National Park Service NR - Northern Rockies NW - Northwest RM - Rocky Mountain Department of Agriculture: SA - Southern Area FS – USDA Forest Service SO - Southern California SW - Southwest Department of Defense: DOD CIFFC - Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre Department of Homeland Security: FEMA - Federal Emergency Management Agency ESF #4 – Emergency Support Function 4, Firefighting Department of Commerce: NWS - National Weather Service Department of Energy: DOE ST – State ST/OT – State and Other combined OT – Other PRI – Private CNTY – County CN – Canada AU – Australia NZ – New Zealand 2 Preface Statistics used in this report were gathered from the interagency Fire and Aviation Management Web Applications (FAMWEB) system, which includes the Situation Report and Incident Status Summary (ICS-209) programs1. -

Collective Intelligence in Emergency Management 1

Collective Intelligence in Emergency Management 1 Running head: COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE IN EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT: SOCIAL MEDIA’S ROLE IN THE EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTER Collective Intelligence in Emergency Management: Social Media's Emerging Role in the Emergency Operations Center Eric D. Nickel Novato Fire District Novato, California Collective Intelligence in Emergency Management 2 CERTIFICATION STATEMENT I hereby certify that this paper constitutes my own product, that where the language of others is set forth, quotation marks so indicate, and that appropriate credit is given where I have used the language, ideas, expressions, or writings of another. Signed: __________________________________ Collective Intelligence in Emergency Management 3 ABSTRACT The problem was that the Novato Fire District did not utilize social media technology to gather or share intelligence during Emergency Operations Center activations. The purpose of this applied research project was to recommend a social media usage program for the Novato Fire District’s Emergency Operations Center. Descriptive methodology, literature review, two personal communications and a statistical sampling of fire agencies utilizing facebook supported the research questions. The research questions included what were collective intelligence and social media; how was social media used by individuals and organizations during events and disasters; how many fire agencies maintained a facebook page and used them to distribute emergency information; and which emergency management social media programs should be recommended for the Novato Fire District’s Emergency Operations Center. The procedures included two data collection experiments, one a statistical sampling of United States fire agencies using facebook, to support the literature review and research questions. This research is one of the first Executive Fire Officer Applied Research Projects that addressed this emerging subject. -

CALIFORNIA PROFESSIONAL FIREFIGHTERS 1780 Creekside Oaks Drive, Sacramento, CA 95833

CALIFORNIA PROFESSIONAL FIREFIGHTERS 1780 Creekside Oaks Drive, Sacramento, CA 95833 Adin Fire Protection District Aerojet Fire Services Ken Richardson, Fire Chief Greg Granados, Fire Chief P.O. Box 16 P.O. Box 13222, BLD 02-028 Adin, CA 96006 Sacramento, CA 95813 Office: (530) 299-4700 Fax: Office: (916) 355-4251 Fax: (916) 355-4035 General Email: General Email: Chief Email: Chief Email: [email protected] Dept. Web: Dept. Web: City Web: City Web: MACS Designator: ADI Personnel: Mostly Volunteer MACS Designator: AFS Personnel: Paid County: Modoc Fire Dept. ID: 25005 County: Sacramento Fire Dept. ID: 34003 Agnews Developmental Center Air National Guard Fire Dept. Mike Horton, Fire Chief Christopher Diaz, Fire Chief 3500 Zanker Road 5323 E. McKinley Ave. San Jose, CA 95134 Fresno, CA 93727 Office: (408) 451-7403 Fax: (408) 451-7411 Office: (559) 454-5315 Fax: (559) 454-5329 General Email: General Email: Chief Email: [email protected] Chief Email: [email protected] Dept. Web: Dept. Web: City Web: City Web: MACS Designator: ASH Personnel: Paid MACS Designator: REE Personnel: Paid County: Santa Clara Fire Dept. ID: 43490 County: Fresno Fire Dept. ID: 10800 Alameda City Fire Dept. Alameda County Fire Dept. Doug Long, Fire Chief David Rocha, Fire Chief 1300 Park Street 6363 Clark Avenue Alameda, CA 94501 Dublin, CA 94568 Office: (510) 337-2100 Fax: (510) 521-7851 Office: (925) 833-3473 Fax: (925) 875-9387 General Email: [email protected] General Email: Chief Email: [email protected] Chief Email: [email protected] Dept. Web: www.cityofalamedaca.gov/City-Hall/Fire Dept. -

Sept 2021 Complete Package

SNC Governing Board Meeting September 2, 2021 This meeting will be held online. Image - Mt. Shasta seen from Ahjumawi Lava Springs State Park Board Meeting Agenda September 2, 2021 — Virtual Board Meeting September 2, 2021 9:00 a.m. – 2:00 p.m. (End time is approximate) Board Meeting 9:00 a.m. – 2:00 p.m. (End time is approximate) Pursuant to Executive Order N-8-21 issued by Governor Gavin Newsom on June 11, 2021, certain provisions of the Bagley-Keene Open Meeting Act are suspended due to a State of Emergency in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Consistent with this Executive Order, the September 2021 Sierra Nevada Conservancy (SNC) Governing Board Meeting will be conducted virtually through the Zoom Webinar Platform. Members of the public may join the meeting using either of the following steps: Join the webinar Or Dial either of these numbers and enter the conference code to join the meeting by telephone: Dial: USA 636 651 3142 US Toll USA 877 402 9757 US Toll-free Conference code: 347291 Meeting materials are available on the SNC Board Meetings page (https://sierranevada.ca.gov/our-board/board-meetings/). Members of the public can make comments on agenda items during the meeting by using either method of joining the meeting – virtually or telephonically – and by following the moderator’s directions on how to indicate their interest in speaking. Public comment will be taken at the appropriate time during each agenda item and during the Public Comment agenda item at the end of the meeting for non-agenda items.