A Textual Analysis of Orphan Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orphan Black"

CLONING THE IDEAL? UNPACKING THE CONFLICTING IDEOLOGIES AND CULTURAL ANXIETIES IN "ORPHAN BLACK" Danielle Marie Howell A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2016 Committee: Bill Albertini, Advisor Kimberly Coates © 2016 Dani Howell All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Bill Albertini, Advisor In this project, I undertake a queer Marxist reading of the television series Orphan Black. Specifically, I investigate the portrayal of women and queer characters in order to discover the conflicting dominant and oppositional ideologies circulating in the series. Doing so allows me to reveal cultural anxieties that haunt the series even as it challenges normative power relations. I argue that while Orphan Black’s narrative subverts traditional gender roles, critiques heteronormativity, and offers sexually fluid queer characters, the series still reifies the traditionally ideal Western female body—thin, attractive, legibly gendered, and fertile. I draw on Antonio Gramsci’s theory of ideology and hegemony, Heidi Hartman’s analysis of Marxism and feminism, and Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity to unpack the series’ non-normative depiction of gender and its simultaneous reliance on a stable gender binary. I frame my argument with Todd Gitlin’s understanding of hegemony’s ability to domesticate radical ideas in television. I argue that Orphan Black imagines spaces and scenarios that offer the potential to liberate women from heteronormative expectations and limit patriarchy’s harm. The series privileges a queer female collective and envisions a world where women have freedom from normative conceptions of gender and sexuality. -

English Department Course Descriptions Spring 2017 Macomb

English Department Course Descriptions Spring 2017 Macomb Campus Undergraduate Courses English Literature & Writing ENG 200 Introduction to Poetry Section 1 – Merrill Cole Aim: Marianne Moore’s famous poem, “Poetry,” begins, “I too dislike it.” Certainly many people would agree, not considering that their favorite rap or song lyric is poetry, or perhaps forgetting the healing words spoken at a grandparent’s funeral. We often turn to poetry when something happens in our lives that needs special expression, such as when we fall in love or want to speak at a public event. It is true that poems can be difficult, but they can also ring easy and true. Poems may cause us to think hard, or make us feel something deeply. This course offers a broad introduction to poetry, across time and around the globe. The emphasis falls, though, on contemporary poetry more relevant to our everyday concerns. For most of the semester, the readings are organized around formal topics, such as imagery, irony, and free verse. The course also attends to traditional verse forms, which are not only still in use, but also help us better to understand contemporary poetry. Toward the end of the semester, we shift focus to look at two important books of poetry, Frank O’Hara’s 1964 Lunch Poems and Kim Addonizio’s 2000 Tell Me. Although Marianne Moore recognizes that many people “dislike” poetry, she insists that “one discovers in / it after all, a place for the genuine.” William Carlos Williams concurs: ‘ Look at what passes for the new. You will not find it there but in despised poems. -

American Odyssey,' 'Last Ship,' 'Orphan Black' and More on Day 2 of Wonder-Con

'American Odyssey,' 'Last Ship,' 'Orphan Black' and more on Day 2 of Wonder-Con 04.05.2015 Day 2 of WonderCon 2015 has arrived and with it comes oodles of panels for shows about to premiere. The Last Ship (TNT) TNT joined the fray on Saturday, with banners advertising the second season of the show, as well as brand new "R U Immune 2?" t-shirts for those that attended the show's panel. TNT also released a season-two trailer on Friday. The Last Ship premieres June 28 at 9/8 c. The Messengers (CW) In Attendance: creator Eoghan O'Donnell; Executive Producer Trey Callaway; stars Jon Fletcher, Shantel VanSanten, Craig Frank, Diogo Morgado, Anna Diop, Joel Courtney and J.D. Pardo. CW's newest genre show certainly has a high concept: five different characters are given gifts and are tasked with the responsibility to prevent the end of days on Earth. Given the Easter weekend background and the appearance of angels and a Devil-like character in its pilot, it's easy to see the show's religious themes. But, Trey Callaway explains, "it's not a show about religion. It's a show about faith." Shantel VanSanten continues, "it's not about a specific faith or message, it's about coming together." This is a theme Callaway hopes can be explored "over many seasons." While The Messengers is about hope, that's not the show's main priority. "I'm a big sucker for a rollercoaster. Our first job is to entertain in a way a rollercoaster does. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

CFC Honours Orphan Black Creators Graeme Manson and John Fawcett with Award for Creative Excellence

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CFC Honours Orphan Black Creators Graeme Manson and John Fawcett with Award for Creative Excellence Award to be presented by writer and showrunner Hart Hanson and CFC founder Norman Jewison at CFC’s annual L.A. event Toronto, March 17, 2015 – The Canadian Film Centre (CFC) is pleased to present alumni Graeme Manson and John Fawcett with the 2015 Award for Creative Excellence for their originality, vision and exciting work on the award-winning, Space original series Orphan Black. This critically acclaimed ground-breaking conspiracy drama has captured audiences around the world and has been hailed as one of television's most compelling genre series, quickly becoming a cult-hit. Award-winning writer and showrunner Hart Hanson (Bones, Backstrom), along with renowned filmmaker and CFC founder Norman Jewison, will present John and Graeme with the CFC’s Award for Creative Excellence at a reception in Beverly Hills on March 26, 2015. “We are truly honoured to present Graeme and John with the 2015 Award for Creative Excellence,” said Slawko Klymkiw, CEO, CFC. “They embody the mission of the CFC – to accelerate the development of exciting talent and projects, to push the creative envelope and to enrich the global entertainment landscape. We are so proud of the remarkable work and talent that has come out of the CFC; John, Graeme and Orphan Black are perfect examples of that world-class talent and content.” The genesis of Orphan Black was developed through the CFC’s Bell Media Prime Time TV Program in 2008 when Graeme was the Showrunner-in-Residence. -

Short-Term Fate of Rehabilitated Orphan Black Bears Released in New Hampshire

Human–Wildlife Interactions 10(2): 258–267, Fall 2016 Short-term fate of rehabilitated orphan black bears released in New Hampshire Wˎ˜˕ˎˢ E. S˖˒˝ˑ1, Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, 56 College Road, Durham, NH 03824, USA [email protected] Pˎ˝ˎ˛ J. Pˎ˔˒˗˜, Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, 56 College Road, Durham, NH 03824, USA A˗ˍ˛ˎˠ A. T˒˖˖˒˗˜, New Hampshire Fish and Game Department, 629B Main Street, Lancaster, NH 03584, USA Bˎ˗˓ˊ˖˒˗ K˒˕ˑˊ˖, P.O. Box 37, Lyme, NH 03768, USA Abstract: We evaluated the release of rehabilitated, orphan black bears (Ursus americanus) in northern New Hampshire. Eleven bears (9 males, 2 females; 40–45 kg) were outfi tted with GPS radio-collars and released during May and June of 2011 and 2012. Bears released in 2011 had higher apparent survival and were not observed or reported in any nuisance behavior, whereas no bears released in 2012 survived, and all were involved in minor nuisance behavior. Analysis of GPS locations indicated that bears in 2011 had access to and used abundant natural forages or habitat. Conversely, abundance of soft and hard mast was lower in 2012, suggesting that nuisance behavior, and consequently survival, was inversely related to availability of natural forage. Dispersal from the release site ranged from 3.4–73 km across both years, and no bear returned to the rehabilitation facility (117 km distance). Rehabilitation appears to be a valid method for addressing certain orphan bear issues in New Hampshire. -

Metaphors of Patriarchy in Orphan Black and Westworld

Feminist Media Studies ISSN: 1468-0777 (Print) 1471-5902 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfms20 Metaphors of patriarchy in Orphan Black and Westworld Olivia Belton To cite this article: Olivia Belton (2020): Metaphors of patriarchy in OrphanBlack and Westworld, Feminist Media Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2019.1707701 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2019.1707701 Published online: 21 Jan 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 70 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfms20 FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2019.1707701 Metaphors of patriarchy in Orphan Black and Westworld Olivia Belton Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Orphan Black (2013–17) and Westworld (2016-) use their science Received 7 August 2018 fiction narratives to create metaphors for patriarchal oppression. Revised 12 November 2019 The female protagonists struggle against the paternalistic scientists Accepted 18 December 2019 and corporate leaders who seek to control them. These series break KEYWORDS away from more liberal representations of feminism on television Science fiction; television; by explicitly portraying how systemic patriarchal oppression seeks patriarchy; cyborgs; to control and exploit women, especially under capitalism. They feminism also engage with radical feminist ideas of separatism and compul- sory heterosexuality. The science fiction plots allow them to deal with feminist issues. Westworld uses computer programming as a metaphor for patriarchal social conditioning, while Orphan Black’s clones recall cyborg feminism. -

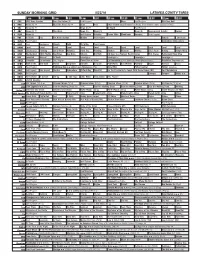

Sunday Morning Grid 5/22/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/22/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid 2016 French Open Tennis First Round. From Roland Garros Stadium in Paris. 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Supervisorial Debate Explore 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program FabLab I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Somewhere Slow (2013) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley Rick Steves Retirement Road Map 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Firehouse Dog ›› (2007) Josh Hutcherson. -

Episode Guide

Episode Guide Episodes 001–050 Last episode aired Saturday August 12, 2017 www.bbcamerica.co.uk c c 2017 www.tv.com c 2017 c 2017 c 2017 www.bbcamerica.co.uk orphanblack.wikia.com www.threeifbyspace.net c 2017 twocentstv.com c 2017 www.metro.us c 2017 c 2017 popinsomniacs.com www.tvgoodness.com c 2017 www.buddytv.com The summaries and recaps of all the Orphan Black episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http: //www.bbcamerica.co.uk and http://orphanblack.wikia.com and http://www.threeifbyspace.net and http:// twocentstv.com and http://www.metro.us and http://www.tvgoodness.com and http://popinsomniacs.com and http://www.buddytv.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on August 14, 2017 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.59 Contents Season 1 1 1 Natural Selection . .3 2 Instinct . .5 3 Variation Under Nature . .7 4 Effects of External Conditions . 11 5 Conditions of Existence . 15 6 Variations Under Domestication . 19 7 Parts Developed in an Unusual Manner . 21 8 Entangled Bank . 25 9 Unconscious Selection . 27 10 Endless Forms Most Beautiful . 29 Season 2 33 1 Nature Under Constraint and Vexed . 35 2 Governed by Sound Reason and True Religion . 39 3 Mingling Its Own Nature With It . 43 4 Governed as It Were by Chance . 47 5 Ipsa Scientia Potestas Est . 51 6 To Hound Nature in Her Wanderings . 55 7 Knowledge Of Causes, And Secret Motion Of Things . -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

2015 Summer Reading

WCU ENGLISH DEPARTMENT SUMMER READING & VIEWING LIST: Faculty Picks 2015 This annual list presents suggestions for summer reading/viewing from individual faculty of the West Chester University English Department. You can also find this list & its predecessors at http://www.wcupa.edu/_academics/sch_cas.eng/facultyPicks.aspx. Book, podcast, film, site: Recommender: 20 Feet From Stardom Maureen McVeigh Trainor Morgan Neville, Director They sing your favorite songs, but you’ve probably never heard of them. This film highlights the backup singers of some of the most iconic American bands and the stark contrast of their lives to those of the famous musicians. Exploring ideas of gender, race, and economics, this film is engaging, thought-provoking, and entertaining, just like the music it includes. I saw this movie on a whim and have been recommending it ever since. It won an Oscar for Best Documentary and is available on Netflix. And, fellow faculty, because of this film, I learned we all have something in common with the woman who inspired the song Brown Sugar as she is now an adjunct professor of languages. 99% Invisible Rodney Mader http://99percentinvisible.org The title comes from a quotation by Buckminster Fuller about the unseen centrality of design to human lives: "Ninety-nine percent of who you are is invisible and untouchable.” A favorite of Ira Glass and the Radiolab team, the production values are excellent, and the stories are cocktail party gold. Recent shows cover the popularity of the Portland airport’s carpet design; the introduction of palm trees to Los Angeles; an electric bulb that has been continuously operating for 113 years; and how you can always tell what used to be a Pizza Hut. -

"She's Not a Real Monster": Orphan Black's Helena and the Monstrous-Feminine Natalie Eisen Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 "She's Not a Real Monster": Orphan Black's Helena and the Monstrous-Feminine Natalie Eisen Scripps College Recommended Citation Eisen, Natalie, ""She's Not a Real Monster": Orphan Black's Helena and the Monstrous-Feminine" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 929. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/929 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SHE’S NOT A REAL MONSTER”: ORPHAN BLACK’S HELENA AND THE MONSTROUS-FEMININE by NATALIE EISEN SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR ANDREJEVIC PROFESSOR CHENG DECEMBER 9, 2016 Eisen 1 The scene opens on a pool of blood in a sink. As the camera skitters madly through a series of fractured images – bloodstained bandages on the countertop, bloodstained gloves holding rubbing alcohol, bloodstained boots and bloodstained skin – the scene echoes with the soundtrack’s mechanical screeches and a woman’s labored gasps of pain. The woman in question is invisible to the audience, at least as a whole body; she is fractured – inhuman – monstrous. The scene blurs and shifts, irrationally, and at last the camera focuses on the woman’s mouth. All she says: “I’m not Beth.” So that is the entirety of her identity: what it is that she is not. Female monsters are defined by their unpredictability, their inability to suit a clear definition.