Issue 6 November 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RARE BOOK AUCTION Wednesday 24Th August 2011 11

RARE BOOK AUCTION Wednesday 24th August 2011 11 68 77 2 293 292 267 54 276 25 Rare Books, Maps, Ephemera and Early Photographs AUCTION: Wednesday 24th August, 2011, at 12 noon, 3 Abbey Street, Newton, Auckland VIEWING TIMES CONTACT Sunday 21st August 11.00am - 3.00 pm All inquiries to: Monday 22nd August 9.00am - 5.00pm Pam Plumbly - Rare book Tuesday 23rd August 9.00am - 5.00pm consultant at Art+Object Wednesday 24th August - viewing morning of sale. Phones - Office 09 378 1153, Mobile 021 448200 BUYER’S PREMIUM Art + Object 09 354 4646 Buyers shall pay to Pam Plumbly @ART+OBJECT 3 Abbey St, Newton, a premium of 17% of the hammer price plus GST Auckland. of 15% on the premium only. www.artandobject.co.nz Front cover features an illustration from Lot 346, Beardsley Aubrey, James Henry et al; The Yellow Book The Pycroft Collection of Rare New Zealand, Australian and Pacific Books 3rd & 4th November 2011 ART+OBJECT is pleased to announce the sale of the last great New Zealand library still remaining in private hands. Arthur Thomas Pycroft (1875 – 1971) a dedicated naturalist, scholar, historian and conservationist assembled the collection over seven decades. Arthur Pycroft corresponded with Sir Walter Buller. He was extremely well informed and on friendly terms with all the leading naturalists and museum directors of his era. This is reflected in the sheer scope of his collecting and an acutely sensitive approach to acquisitions. The library is rich in rare books and pamphlets, associated with personalities who shaped early New Zealand history. -

New Zealand and the Colonial Writing World, 1890-1945

A DUAL EXILE? NEW ZEALAND AND THE COLONIAL WRITING WORLD, 1890-1945 Helen K. Bones A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at the University of Canterbury March 2011 University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand 1 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................... 1 Index of Tables ................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... 3 Abstract ............................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5 PART ONE: NEW ZEALAND AND THE COLONIAL WRITING WORLD 22 Chapter One – Writing in New Zealand ................................................. 22 1.1 Literary culture in New Zealand ................................................. 22 1.2 Creating literature in New Zealand ..................................... 40 Chapter Two – Looking Outward ............................................................. 59 2.1 The Tasman Writing World ................................................. 59 2.2 The Colonial Writing World ................................................. 71 Chapter Three – Leaving New Zealand ................................................ -

Montague Harry Holcroft, 1902 – 1993

150 Montague Harry Holcroft, 1902 – 1993 Stephen Hamilton Born in Rangiora on the South Island of New Zealand on 14 May 1902, Montague Harry Holcroft was the son of a grocer and his wife and the second of three boys. When his father’s business failed in 1917, he was forced to leave school and begin his working life in the office of a biscuit factory. Two years later he abandoned his desk in search of adventure, working on farms throughout New Zealand before crossing the Tasman Sea to Sydney, Australia in the company of his friend Mark Lund. Here he returned to office work and married his first wife, Eileen McLean, shortly before his 21st birthday. Within three years the marriage ended and Holcroft returned to New Zealand. However, during his sojourn in Sydney his emerging passion for writing had borne fruit in stories published in several major Australian magazines. With aspirations to become a successful fiction writer, he submitted a manuscript to London publisher John Long. Beyond the Breakers appeared in 1928. After a brief interlude on the staff of a failing Christchurch newspaper, he departed for London in late 1928 with a second novel stowed among his luggage. Despite having stories accepted by a number of British magazines, London proved unsympathetic to his efforts, even after a second novel, The Flameless Fire, appeared in 1929. After visiting France and North Africa, and with the Depression beginning to bite, Holcroft elected to again return to New Zealand. In Wellington in July 1931 he married Aralia Jaslie Seldon Dale. -

View Complete Text Here

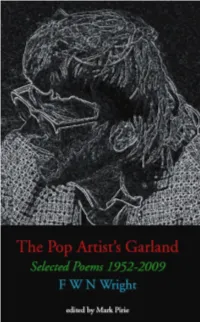

1 The celebrated poet Eileen Duggan and the influential editor J H E Schroder were among the early appreciators of Niel Wright’s verse. This selection draws on six decades of writing, 120 Books of Wright’s epic poem The Alexandrians as well as his Post-Alexandrian work, and displays an extraordinary and wide-ranging talent. Avoiding the narrow constraints of a regionalist poetry or the bohemian outlook of the Wellington group of poets, Wright has consistently forged his own path and poetic style since the 1950s often at odds with contemporary fashion and modernist/postmodernist tendencies. As with the English poet Robert Bridges, he has sought above all to renew the prosody. Skilled in many traditional forms such as the triolet, the epigram, the ballad, the ode, the sonnet and the lyric as well as classical and epic narrative verse, the selection presents for the first time a generous sampling of his prolific output and reveals his original and remarkable voice in New Zealand poetry. … a delight to see the classics revived in a comparatively new land and in an age alien to them. – Eileen Duggan, personal correspondence … a witty turn of phrase … – James K Baxter, New Zealand Listener … a poet of unusual range … Mr Wright’s use of prosody and his use of half-rhymes and assonances often recall those of Wilfred Owen. – Peter Dronke, Landfall … a pot-pourri of astonishing richness, lyrical in its presentation but with a strong narrative thread. – Michael Gifkins, New Zealand Listener 2 THE POP ARTISTS GARLAND Frank William Nielsen Wright was born in Sydenham, Christchurch, in 1933 and educated at Christchurch Boys High School and Canterbury University and Victoria University of Wellington (where he was awarded his PhD in 1974). -

Newton JGH.Pdf (6.164Mb)

"That•s me trying to step out of that sentence" An Approach to Some Recent Hew Zealand Poetry A thesis submitted in partial :fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master o:f Arts in English in the University of Canterbury by J .G.H. Hewton University of Canterbury 1981 CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE ABSTRACT IHTR0DUCTIOR........................................ 1 (1) FROM AKITIO TO JERUSALEM ........................ 10 i) The geography master ....................... 11 ii) The trick of walking naked ................. 24 iii) The slave of God .........•................•... 34 1 V) "My Gift to you, Col in" ..................... 52 V) "The third-person you"; the "first-person you" ...................... 59 (2) "THE SEVEN TI ES" ....................................•• 70 i) The embrace of "1" and "you".............. 71 ii) "Your sentence comes back at you".......... 100 iii) ApproachinC Manhire............................ 120 CHAPTER PAGE (3) WILY TE TUTUA'S OUTLAW GAMBOL .......•........•.. 142 i) The appeal to Janguage ... u ... , ........... 143 ii) Holy sonnets .................................. 146 iii) WorkinC for the Law ........ , .............. 155 iv) SteppinC out ................................. 16 q. v) The uses of tee hnoloC y .................... 178 Vi) Permanent revolution ........................ 165 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................... 192. SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY ................................... 193 ABSTRACT This thesis addresses itself to changes which came over Hew Zealand poetry in the early 1970s. It discusses in detail the work of three poets whose public careers began in this period: Ian Wedde, Murray Edmond and Bill Manhire, Its perspective also necessitates the inclusion of one poet from either side of this chronological site: it opens by considering James K. Baxter and closes with a look at Leigh Davis. My focus is on the arrangement of pronouns, and on the way in which particular pronominal formations evolve through the work of these five poets. -

The Early Poetry of Elizabeth Riddell (1907-1998)

ka mate ka ora: a new zealand journal of poetry and poetics Issue 12 March 2013 Made in New Zealand: The Early Poetry of Elizabeth Riddell (1907-1998) Marcia Russell Editor’s Note: This essay is taken from Marcia Russell’s Master of Literature thesis (2012) at the University of Auckland. We are very pleased to have Marcia’s permission to publish this work. The whole project was to have been a Doctoral thesis and no one was better placed than Marcia, with her literary and journalistic expertise and understanding, to write about and recover for us the life and work, and especially the New Zealand context and origins, of Elizabeth Riddell, poet and journalist. Sadly Marcia died towards the end of 2012 and was unable to complete her undertaking. We are grateful to Marcia’s supervisors, Dr Jan Cronin and Professor Michele Leggott, for enabling this publication and to Heidi Logan for her copy editing on the text. - Murray Edmond 2 Part One: ‘A writing life but not a literary life’1 Elizabeth Richmond Riddell was born on 21 March 1907 in Napier, the second daughter of Violet Whitbread Riddell (nee Williams) and Richmond John Sydney Riddell. Her father was an accountant and solicitor for a Napier stock and station agency, her mother was the third of five children born to George and Emily Williams, all of Napier. Violet’s three sisters, Rose, Myra and Leslie all lived, like the Riddells, on the hills above Napier; the youngest sibling, Patrick, eventually married and settled in Wellington. Riddell’s paternal grandfather, George Riddell, who was the deputy-registrar in the Napier Lands and Deeds Registry, died unexpectedly while cycling to Western Spit on the Petane Road, the year before Riddell was born. -

Spring 2014, Volume 5, Issue 3

. Poetry Notes Spring 2014 Volume 5, Issue 3 ISSN 1179-7681 Quarterly Newsletter of PANZA Zealand. She was included in a Inside this Issue Welcome bibliography of legends/myths for her collection Māori Love Legends Hello and welcome to issue 19 of published after the First World War in Welcome Poetry Notes, the newsletter of PANZA, 1920. 1 the newly formed Poetry Archive of As with some other poets profiled Mark Pirie on Marieda New Zealand Aotearoa. recently in Poetry Notes, Batten does Batten (1875-1933) Poetry Notes will be published quarterly not appear in any New Zealand and will include information about anthology that I’m aware of, but she is Classic New Zealand goings on at the Archive, articles on listed with other New Zealand poets of poetry by Noeline historical New Zealand poets of interest, this period in New Zealand Literature 6 Gannaway occasional poems by invited poets and a Authors’ Week 1936: Annals of New record of recently received donations to Zealand Literature: being a List of New Comment on Travis the Archive. Zealand Authors and their works with Wilson (1924-1983) 7 Articles and poems are copyright in the introductory essays and verses, page 40: names of the individual authors. National Poetry Day poem: “Batten, Ida Marieda (Mrs Cook [sic]). The newsletter will be available for free 1915, Star dust and sea foam (v); 9 Jean Batten download from the Poetry Archive’s c1918, Love-life (v); 1920, Maori love website: legends (v); 1925, Silver nights (v).” Tribute to Warren Dibble Marieda Batten appears with the New 10 http://poetryarchivenz.wordpress.com Zealand poets Jessie Mackay, Alan E. -

Issue 4 November 2009

broadsheet new new zealand poetry Issue No. 4, November 2009 Editor: Mark Pirie THE NIGHT PRESS WELLINGTON / 1 Poems copyright 2009, in the names of the individual contributors Published by The Night Press Cover drawing of Ruth Gilbert in Samoa by Michael OLeary broadsheet is published twice a year in May and November Subscriptions to: The Editor 97/43 Mulgrave Street Thorndon Wellington 6011 Aotearoa / New Zealand http://headworx.eyesis.co.nz Cost per year $12.00 for 2 issues. Cheques payable to: HeadworX ISSN 1178-7805 (Print) ISSN 1178-7813 (Online) Essay on Ruth Gilbert copyright F W N Wright 2009 Please Note: At this stage no submissions will be read. The poems included are solicited by the editor. All submissions will be returned. Thank you. 2 / Contents PREFACE / 5 JEANNE BERNHARDT / 6 ALISTAIR TE ARIKI CAMPBELL / 7 MEG CAMPBELL / 9 JILL CHAN / 11 BILL DACKER / 13 LYNN DAVIDSON / 15 MICHAEL DUFFETT / 17 A R D FAIRBURN / 20 JAN FITZGERALD / 21 RUTH GILBERT / 22 MICHAEL HARLOW / 26 SIOBHAN HARVEY / 27 LEONARD LAMBERT / 29 MICHAEL STEVEN / 30 BRIAN TURNER / 31 ESSAY FEATURE / 32 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS / 40 / 3 Acknowledgements Grateful acknowledgement is made to the editors and publishers of the following collections where the following poems in this issue first appeared: Jeanne Bernhardt: Damians Poem from 26 Poems (Dunedin: Kilmog Press, 2009). Jill Chan: The Blind One from These Hands Are Not Ours (Paekakariki: ESAW, 2009). Michael Duffett: The poem Sarah was recorded on the jazz CD, Within and without (MusicLabs, 1999), with James Hackworth. A R D Fairburn: Jazz from Count Potocki de Montalk, the all time bad boy of Aotearoa letters: news of some recent developments in Potocki studies: a report, F W N Wright (Wellington: Cultural and Political Booklets, 1997). -

Autumn 2016, Volume 7, Issue 1

. Poetry Notes Autumn 2016 Volume 7, Issue 1 ISSN 1179-7681 Quarterly Newsletter of PANZA research journal and I was paid a 6- Inside this Issue Welcome month bonus in cash every summer. So, 18 months salary for half a year’s work. Hello and welcome to issue 25 of The idea is not to make you a lazy, Welcome Poetry Notes, the newsletter of PANZA, privileged academic but a hard-working 1 the newly formed Poetry Archive of responsible one. It worked that latter Michael Duffett on New Zealand Aotearoa. way with me. I settled down to write a New Zealand in 1979 Poetry Notes will be published quarterly book - The Variety of English and will include information about Expression - I had been contemplating Poetry by Eileen Van Trigt goings on at the Archive, articles on for years, wrote in my office, wrote in a historical New Zealand poets of interest, vacation cottage on the Izu Peninsula, 2 occasional poems by invited poets and a wrote at home and eight chapters a year record of recently received donations to In Memoriam: Ruth Gilbert came out in the annual English and 1917-2016 the Archive. American Cultural Studies Research 4 Articles and poems are copyright in the Journal of the university. I went on to names of the individual authors. write a sequel - The Growth of English Ruth Gilbert’s The Luthier The newsletter will be available for free by Niel Wright Fiction - towards the end of my stay in download from the Poetry Archive’s 5 Japan and in what turned out to be my website: last year I also taught on an adjunct basis at The University of the Sacred Rachel Bush (1941-2016) http://poetryarchivenz.wordpress.com 7 Heart, an institution which decided to invite Father Frank McKay to come Comment on James K from New Zealand and lecture on a 8 Baxter’s Complete Prose Michael Duffett on guest basis on Katherine Mansfield. -

Poetry Notes

. Poetry Notes Spring 2012 Volume 3, Issue 3 ISSN 1179-7681 Quarterly Newsletter of PANZA Caddick as ‘declaiming passionate Inside this Issue Welcome verses’ and ‘ignoring his wound’ fresh from the trenches. Caddick who had Hello and welcome to issue 11 of returned from the First World War and Welcome Poetry Notes, the newsletter of PANZA, by then become a teacher at Wellington 1 the newly formed Poetry Archive of College was also a former student at Mark Pirie on The Old Clay New Zealand Aotearoa. Victoria University College. It was at Patch (Victoria College) Poetry Notes will be published quarterly Victoria that Caddick wrote verses, anthology and will include information about edited and contributed to The Spike (the goings on at the Archive, articles on student magazine) and appeared in the historical New Zealand poets of interest, Classic New Zealand influential anthology of verse and song, poetry by Rev. J H Haslam occasional poems by invited poets and a The Old Clay Patch, edited by fellow 5 record of recently received donations to undergrad students, F A de la Mare and the Archive. S Eichelbaum. Cricket poetry references New publication of Robert The newsletter will be available for free J Pope’s poetry abound within the pages of this book. 6 download from the Poetry Archive’s The Old Clay Patch contained a website: significant amount of university Comment on Louis capping, extravaganza and sporting Johnson by Niel Wright http://poetryarchivenz.wordpress.com songs as well as verse. My cricket 7 poetry anthology, A Tingling Catch, Comment on Tiki Cootes took its title from a line by one of the Mark Pirie on The Old Victoria songwriters of the period, 9 Seaforth Simpson Mackenzie, a future Clay Patch (Victoria lawyer: ‘For the wicket true, and the New publication by College) anthology field in fettle, / and the man who’s safe 10 PANZA member for a tingling catch’ (‘Sports Chorus’, 1907). -

Notes from Prue

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Social and Literary Constraints On Women Writers In New Zealand 1945-1970 By Michael John O‘Leary A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Gender and Women‘s Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2011 Contents Contents ........................................................................................................... ii Abstract ........................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ vi Chapter 1 Introduction .................................................................................... 1 Motivation for writing this thesis ......................................................................... 4 Why write this thesis in GWS ............................................................................. 5 Chapter 2 Methodology/Literature Review .................................................... 9 Feminist methodology ........................................................................................ 9 Literature Review ............................................................................................. 18 Selection of the Women Writers ....................................................................... 22 -

(Ca.); Thomas Lodge; William Warner (Ca

1558 ELIZABETH I (-1603) Births Chidiock Tichborne (ca.); Thomas Lodge; William Warner (ca. 1558-59); Robert Greene (1558 baptized) 1559 • The Mirror of Magistrates, with 20 tragic tales; enlarged repeatedly until 1609 Births George Chapman 1560 Births Anthony Munday, baptized; Sir John Harington (?), baptized 1561 • Julius Caesar Scaliger's poetics published in France Births Mary Herbert, countess of Pembroke; Robert Southwell (?) 1562 Births Henry Constable; Samuel Daniel; Nicholas Grimald Deaths Nicholas Grimald (ca.); William Gray of Reading (ca.) 1563 • Barnabe Googe's Eglogs, Epytaphes, and Sonettes • Second edition of The Mirror of Magistrates, including Thomas Sackville's Induction and Complaint Births John Dowland (ca.); Michael Drayton; Sir Robert Sidney (Philip's younger brother); Joshua Sylvester (?) Floruit Thomas Newberry 1564 Births Christopher Marlowe, baptized on Feb. 6; William Shakespeare, baptized on April 26 in Stratford upon Avon parish church 1565 • Arthur Golding's translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses, books I-IV, published, completed in 1575 Births John Davies (ca. 1564-65); Francis Meres (ca. 1565-66) 1566 • Isabella Whitney's The Copy of a Letter (1566-67) Births John Hoskyns; James I of England (James VI of Scotland). 1567 Births Thomas Campion; Thomas Nashe 1568 • John Skelton's poems published Births Sir Henry Wotton 1569 • Barnabe Barnes' sonnet sequence Parthenophil and Parthenophe Births Sir John Davies; Emilia Lanyer, née Bassano 1570 Births Sir Robert Aytoun (Scotland); Thomas Bateson (?); Thomas Dekker