The North-South Institutions: from Blueprint to Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of Meeting of Letterkenny Electoral

MINUTES OF MUNICIPAL DISTRICT OF LETTERKENNY MEETING HELD IN THE LETTERKENNY PUBLIC SERVICES CENTRE ON TUESDAY, 13TH MARCH, 2018 MDL 93/18 MEMBERS PRESENT Cllr. Liam Blaney Cllr. Ciaran Brogan Cllr. Adrian Glackin Cllr. Jimmy Kavanagh Cllr. James Pat McDaid Cllr. Michael McBride Cllr. Ian McGarvey Cllr. Gerry McMonagle Cllr. John O’Donnell Cllr. Dessie Shiels MDL94/18 OFFICIALS PRESENT Cliodhna Campbell, Senior Engineer, Roads & Transportation (Part) Fergal Doherty, S.E.E./Area Manager, Roads & Transportation Donna Callaghan, Assistant Planner Joe Ferry, Senior Executive Scientist, County Laboratory Eunan Kelly, Area Manager, Corporate & Housing Services Linda McCann, Senior Staff Officer Christina O’Donnell, Development Officer Liam Ward, Director of Service The meeting was chaired by Mayor, Cllr. Jimmy Kavanagh. MDL95/18 APOLOGIES Martin McDermott, Executive Planner MDL96/18 ADOPTION OF MINUTES OF MDL MEETING HELD ON 13thFEBRUARY, 2018 On the proposal of Cllr. Gerry McMonagle and seconded by Cllr. Ciaran Brogan, the Minutes of MDL Meeting held on 9th January, 2018 were adopted. MDL97/18 PUBLIC LIGHTING PROGRAMME UPDATE Cliodhna Campbell went through the report “Public Lighting and Energy Efficiency” dated March 2018 circulated with the agenda and updated Members on the current Public Lighting LED Replacement Programme to address the matter of cessation of production of SOX type lamp bulbs over a five year period. The report was circulated to Members are part of the Roads Agenda. Cliodhna Campbell then circulated a further report “Supplementary Note to Public Lighting Update March 2018” along with a replacement schedule for the three years of the programme. Members welcomed the report and their queries in relation to energy cost savings, period and cost of the proposed loan, quality of the light etc were addressed by Cliodhna Campbell. -

University of Copenhagen

The General Election of 2011 in the Republic of Ireland: All Changed Utterly? Little, Conor Published in: West European Politics DOI: 10.1080/01402382.2011.616669 Publication date: 2011 Citation for published version (APA): Little, C. (2011). The General Election of 2011 in the Republic of Ireland: All Changed Utterly? West European Politics, 34(6), 1304-1313. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2011.616669 Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 The general election of 2011 in the Republic of Ireland: all changed utterly? Word count: 4,230 Conor Little, European University Institute Email: [email protected] This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in West European Politics on 1 November 2011, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01402382.2011.616669 Full citation: Little, C. 2011. ‘The general election of 2011 in the Republic of Ireland: all changed utterly?’, West European Politics 34 (6): 1304-1313. Acknowledgement I would like to acknowledge the contribution of the late Professor Peter Mair (1951-2011) to this election review article, both as Editor of West European Politics and as this author's mentor at the European University Institute. 1 On 9 March 2011, the 31 st Dáil (the lower house of the Irish parliament) convened for the first time and elected Enda Kenny of Fine Gael as Taoiseach (prime minister) by 117 votes to 27. Breaking with tradition, a depleted Fianna Fáil party did not propose an alternative candidate and abstained from the vote. Kenny's election brought to an end Fianna Fáil's fourteen consecutive years in Cabinet on the back of three successful elections in 1997, 2002 and 2007. -

Potential Outcomes for the 2007 and 2011 Irish Elections Under a Different Electoral System

Publicpolicy.ie Potential Outcomes for the 2007 and 2011 Irish elections under a different electoral system. A Submission to the Convention on the Constitution. Dr Adrian Kavanagh & Noel Whelan 1 Forward Publicpolicy.ie is an independent body that seeks to make it as easy as possible for interested citizens to understand the choices involved in addressing public policy issues and their implications. Our purpose is to carry out independent research to inform public policy choices, to communicate the results of that research effectively and to stimulate constructive discussion among policy makers, civil society and the general public. In that context we asked Dr Adrian Kavanagh and Noel Whelan to undertake this study of the possible outcomes of the 2007 and 2011 Irish Dail elections if those elections had been run under a different electoral system. We are conscious that this study is being published at a time of much media and academic comment about the need for political reform in Ireland and in particular for reform of the electoral system. While this debate is not new, it has developed a greater intensity in the recent years of political and economic volatility and in a context where many assess the weaknesses in our political system and our electoral system in particular as having contributed to our current crisis. Our wish is that this study will bring an important additional dimension to discussion of our electoral system and of potential alternatives. We hope it will enable members of the Convention on the Constitution and those participating in the wider debate to have a clearer picture of the potential impact which various systems might have on the shape of the Irish party system, the proportionality of representation, the stability of governments and the scale of swings between elections. -

20200214 Paul Loughlin Volume Two 2000 Hrs.Pdf

DEBATING CONTRACEPTION, ABORTION AND DIVORCE IN AN ERA OF CONTROVERSY AND CHANGE: NEW AGENDAS AND RTÉ RADIO AND TELEVISION PROGRAMMES 1968‐2018 VOLUME TWO: APPENDICES Paul Loughlin, M. Phil. (Dub) A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Professor Eunan O’Halpin Contents Appendix One: Methodology. Construction of Base Catalogue ........................................ 3 Catalogue ....................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. BASE PROGRAMME CATALOGUE CONSTRUCTION USING MEDIAWEB ...................................... 148 1.2. EXTRACT - MASTER LIST 3 LAST REVIEWED 22/11/2018. 17:15H ...................................... 149 1.3. EXAMPLES OF MEDIAWEB ENTRIES .................................................................................. 150 1.4. CONSTRUCTION OF A TIMELINE ........................................................................................ 155 1.5. RTÉ TRANSITION TO DIGITISATION ................................................................................... 157 1.6. DETAILS OF METHODOLOGY AS IN THE PREPARATION OF THIS THESIS PRE-DIGITISATION ............. 159 1.7. CITATION ..................................................................................................................... 159 Appendix Two: ‘Abortion Stories’ from the RTÉ DriveTime Series ................................ 166 2.1. ANNA’S STORY ............................................................................................................. -

Lessons from the Irish Citizenship Referendum

“Citizenship Matters”: Lessons from the Irish Citizenship Referendum J. M. Mancini Graham Finlay American Quarterly, Volume 60, Number 3, September 2008, pp. 575-599 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/aq.0.0034 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/aq/summary/v060/60.3.mancini.html Access Provided by National University of Ireland, Maynooth at 01/11/11 12:37PM GMT “Citizenship Matters” | 575 “Citizenship Matters”: Lessons from the Irish Citizenship Referendum J. M. Mancini and Graham Finlay n 1916, armed insurrectionists revolted against the chief ally of the United States. The rebels surrendered quickly, but were punished severely: 15 were Iexecuted, and 3,500 faced imprisonment. Curiously, the British govern- ment spared one of the rebel leaders, propelling him to take a central role in an ongoing and ultimately successful campaign to subvert British rule. Even more curiously, nearly fifty years later, in 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson welcomed this aging insurrectionist—who had abandoned his belief in the use of force against the British only a few years before—to the White House on a state visit. Johnson’s greeting to Eamon de Valera, by then the president of the Republic of Ireland, immediately suggests why he was spared: “This is the country of your birth, Mr. President . this will always be your home.”1 Although de Valera, the American-born son of an Irish mother and a Spanish father, lived in the United States for fewer than three years, both the Brit- ish courts and Johnson after them understood de Valera to be an American citizen—despite his expatriation, despite his participation in armed political struggle, and despite his ascent to the leadership of a foreign government. -

Finance Accounts

FINANCE ACCOUNTS Audited Financial Statements of the Exchequer For the Financial Year 1st January 2004 to 31st December 2004 Presented to both Houses of the Oireachtas pursuant to Section 4 of the Comptroller and Auditor General (Amendment) Act, 1993. BAILE ÁTHA CLIATH ARNA FHOILSIÚ AG OIFIG AN tSOLÁTHAIR Le ceannach díreach ón OIFIG DHÍOLTA FOILSEACHÁN RIALTAIS TEACH SUN ALLIANCE, SRÁID THEACH LAIGHEAN, BAILE ÁTHA CLIATH 2, nó tríd an bpost ó FOILSEACHÁIN RIALTAIS, AN RANNÓG POST-TRÁCHTA, 51 FAICHE STIABHNA, BAILE ÁTHA CLIATH 2, (Teil: 01 - 6476834/35/36/37: Fax: 01 - 6476843) nó trí aon díoltóir leabhar. ______ DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2. or by mail order from GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS, POSTAL TRADE SECTION, 51 ST. STEPHEN'S GREEN, DUBLIN 2, (Tel: 01 - 6476834/35/36/37; Fax: 01 - 6476843) or through any bookseller. ______ (Prn. XXXX) Price €XXX © Copyright Government of Ireland 2005. Catalogue Number F/xxx/xxxx ISBN xxxxxx Contents Foreword 5 AUDIT REPORT 6 EXCHEQUER ACCOUNT 7 PART 1 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF EXCHEQUER RECEIPTS AND ISSUES AND GUARANTEED LIABILITIES CURRENT : Tax Revenue 11 Non-Tax Revenue 12 Issues for Current Voted Expenditure 14 Payments charged to Central Fund in respect of Salaries, Allowances, Pensions etc. (a) 15 Payments to the European Union Budget 15 Other Non-Voted Current Expenditure 16 CAPITAL : Issues for Capital Voted Expenditure 17 Loan Transactions 18 Share Capital acquired in State-sponsored Bodies 19 Investments in International Bodies under International Agreements 20 Investments - Shares of Sundry Undertakings 20 Receipts from the European Union 21 Payments to the European Union 21 Other Capital Receipts 22 Other Capital Payments 22 OTHER : Guaranteed Liabilities 23 Further Breakdown of Payments charged to Central Fund in respect of Salaries, Allowances, Pensions etc. -

Tony Heffernan Papers P180 Ucd Archives

TONY HEFFERNAN PAPERS P180 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2013 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Administrative History iv Archival History v CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content vi System of Arrangement viii CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access x Language x Finding Aid x DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note x ALLIED MATERIALS Published Material x iii CONTEXT Administrative History The Tony Heffernan Papers represent his long association with the Workers’ Party, from his appointment as the party’s press officer in July 1982 to his appointment as Assistant Government Press Secretary, as the Democratic Left nominee in the Rainbow Coalition government between 1994 and 1997. The papers provide a significant source for the history of the development of the party and its policies through the comprehensive series of press statements issued over many years. In January 1977 during the annual Sinn Féin Árd Fheis members voted for a name change and the party became known as Sinn Féin the Workers’ Party. A concerted effort was made in the late 1970s to increase the profile and political representation of the party. In 1979 Tomás MacGiolla won a seat in Ballyfermot in the local elections in Dublin. Two years later in 1981 the party saw its first success at national level with the election of Joe Sherlock in Cork East as the party’s first TD. In 1982 Sherlock, Paddy Gallagher and Proinsias de Rossa all won seats in the general election. In 1981 the Árd Fheis voted in favour of another name change to the Workers’ Party. -

The Irish Student Movement As an Agent of Social Change: a Case Study Analysis of the Role Students Played in the Liberalisation of Sex and Sexuality in Public Policy

The Irish student movement as an agent of social change: a case study analysis of the role students played in the liberalisation of sex and sexuality in public policy. Steve Conlon BA Thesis Submitted for the Award of Doctorate of Philosophy School of Communication Dublin City University Supervisor: Dr Mark O’Brien May 2016 Declaration I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctorate of Philosophy is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ______________________ ID No.: 58869651 Date: _____________ i ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks to my supervisor Dr Mark O’Brien, a tremendous advocate and mentor whom I have had the privilege of working with. His foresight and patience were tested throughout this project and yet he provided all the necessary guidance and independence to see this work to the end. I must acknowledge too, Prof. Brian MacCraith, president of DCU, for his support towards the research. He recognised that it was both valuable and important, and he forever will have my appreciation. I extend my thanks also to Gary Redmond, former president of USI, for facilitating the donation of the USI archive to my research project and to USI itself for agreeing to the donation. -

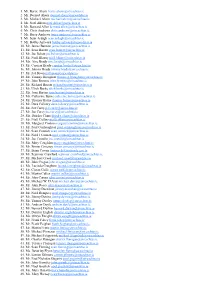

1. Mr. Bertie Ahern [email protected] 2. Mr. Dermot Ahern [email protected] 3. Mr. Michael Ahern [email protected] 4

1. Mr. Bertie Ahern [email protected] 2. Mr. Dermot Ahern [email protected] 3. Mr. Michael Ahern [email protected] 4. Mr. Noel Ahern [email protected] 5. Mr. Bernard Allen [email protected] 6. Mr. Chris Andrews [email protected] 7. Mr. Barry Andrews [email protected] 8. Mr. Seán Ardagh [email protected] 9. Mr. Bobby Aylward [email protected] 10. Mr. James Bannon [email protected] 11. Mr. Sean Barrett [email protected] 12. Mr. Joe Behan [email protected] 13. Mr. Niall Blaney [email protected] 14. Ms. Aíne Brady [email protected] 15. Mr. Cyprian Brady [email protected] 16. Mr. Johnny Brady [email protected] 17. Mr. Pat Breen [email protected] 18. Mr. Tommy Broughan [email protected] 19. Mr. John Browne [email protected] 20. Mr. Richard Bruton [email protected] 21. Mr. Ulick Burke [email protected] 22. Ms. Joan Burton [email protected] 23. Ms. Catherine Byrne [email protected] 24. Mr. Thomas Byrne [email protected] 25. Mr. Dara Calleary [email protected] 26. Mr. Pat Carey [email protected] 27. Mr. Joe Carey [email protected] 28. Ms. Deirdre Clune [email protected] 29. Mr. Niall Collins [email protected] 30. Ms. Margaret Conlon [email protected] 31. Mr. Paul Connaughton [email protected] 32. Mr. Sean Connick [email protected] 33. Mr. Noel J Coonan [email protected] 34. -

North/South Ministerial Council & North-South Bodies

Centre for International Borders Research Papers produced as part of the project Mapping frontiers, plotting pathways: routes to North-South cooperation in a divided island THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE NORTH/SOUTH MINISTERIAL COUNCIL AND THE NORTH-SOUTH BODIES Tim O’Connor Project supported by the EU Programme for Peace and Reconciliation and administered by the Higher Education Authority, 2004-06 ANCILLARY PAPER 5 THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE NORTH/SOUTH MINISTERIAL COUNCIL AND THE NORTH-SOUTH BODIES Tim O’Connor MFPP Ancillary Papers No. 5, 2005 (also printed as IBIS working paper no. 51) © the author, 2005 Mapping Frontiers, Plotting Pathways Ancillary Paper No. 5, 2005 (also printed as IBIS working paper no. 51) Institute for British-Irish Studies Institute of Governance Geary Institute for the Social Sciences Centre for International Borders Research University College Dublin Queen’s University Belfast ISSN 1649-0304 ABSTRACT BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE NORTH/SOUTH MINISTERIAL Tim O’Connor is Joint Secretary of the North/South Ministerial Council, Armagh. A COUNCIL AND THE NORTH-SOUTH BODIES graduate of St Patrick’s College Maynooth, he served in the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs, including postings in Bonn and Washington, and terms as Director This paper sets out the background to the new North-South institutional architecture of the Africa Section, Director of Human Rights Unit, and Deputy Secretary General contained in the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement—the negotiations themselves and of the Forum for Peace and Reconciliation (1994-96). He was part of the Irish Gov- the outcome. Given that much of the detail remained to be further worked out after ernment delegation in the negotiations which led to the Good Friday Agreement. -

OIR : Core Book 53

TUARASCÁIL ón gComhchoiste Fiosrúcháin i dtaobh na Géarchéime Baincéireachta An tAcht um Thithe an Oireachtais (Fiosrúcháin, Pribhléidí agus Nósanna Imeachta), 2013 REPORT of the Joint Committee of Inquiry into the Banking Crisis Houses of the Oireachtas (Inquiries, Privileges and Procedures) Act, 2013 Volume 1: Report Volume 2: Inquiry Framework Volume 3: Evidence Oireachtas OIR : Core Book 53 January 2016 Table of contents – by line of inquiry R5: Clarity and effectiveness of the Government and Oireachtas oversight and role R5d: Appropriateness of relationships between Government , the Oireachtas , banking sector and the property sector Bates Number Description Page [Relevant Pages] DOT00716 018 Letter from Alan Cooke Chief Executive Officer IAVI (Extract) 2-3 [001-002] DOT00727 Letter from Sean McEniff Tyrconnell Group, July 2000 (Extract) 4-6 [001-003] DOT00728 Letter from Taoiseach to Sean McEniff 25 July 2000 (Extract) 7-8 [001-002] Memo to Taoiseach and Letter from Hooke McDonald June 2000 DOT00729 9 (Extract) [001] Fax message from Taoiseach to DoE enclosing letter from Ken DOT00730 10-13 McDonald [001-004] DOT00736 Minutes of Taoiseach’s Meeting with Ken McDonald 20 09 2000 14 [001] DOT00745 Letter from O’Flynn, 27th April, 2004 15 [001] DOT00749 Briefing Note for meeting with O’Flynn 08 July 04 (Extract) 16 [001] DOT00750 Letter from Noel O’Callaghan to Dept of Taoiseach on planning 17-19 [001-003] DOT00751 52 Letter and enclosure from O’Flynn Construction (Extract) 20-23 [001-004] PUB00333 Interview with Brian Dobson 26 Sep -

Hare Coursing and Fox Hunting, You Are in the Majority of the Electorate

Dear Voter, Thank you for taking the time to read our "Irish Politicians and Animal Issues" booklet. If you care about animals and are opposed to the cruelty of activities such as hare coursing and fox hunting, you are in the majority of the electorate. Despite most Irish people wanting cruelty ended, some politicians ignore this and shamelessly work to defend those involved in terrorising, injuring and killing wildlife. In the following pages, you will see where politicians stand. If TDs in your constituency have spoken in favour of cruelty in the past, please contact them now. Encourage them to respect the wishes of the majority and reconsider their stance. How you and your family vote in the next election will help determine if Ireland's next government is one which chooses to protect animals or protect animal abusers. Before you cast your vote, consider the views of each of the candidates. If particular candidates are not included in this booklet, question them directly. We also recommend watching our "Politicians" playlist at www.youtube.com/icabs We believe that Ireland will only ever achieve true greatness, when foxhunting, hare coursing and all forms of cruelty are permanently abolished here. On election day, please choose compassion over cruelty. Thank you. Irish Council Against Blood Sports www.banbloodsports.com The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated ~ Gandhi TDs listed alphabetically Bannon, James . .09 Cowen, Barry . .36 Flanagan, Terence . .64 Barrett, Seán . .10 Creed, Michael . .37 Fleming, Sean . .65 Barry, Tom .