None of the Above: Protest Voting in the World's Largest Democracy*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Voting In-Person Through Physical Secret Ballot

CL 166/13 – Information Note 1 – April 2021 Alternative Voting Modalities for Election by Secret Ballot Introduction 1. This note presents an update on the options for alternative voting modalities for conducting a Secret Ballot at the 42nd Session of the Conference. At the Informal Meeting of the Independent Chairperson with the Chairpersons and Vice-Chairpersons of the Regional Groups on 18 March 2021, Members identified two possible, viable options to conduct a Secret Ballot while holding the 42nd Conference in virtual modality. Namely, physical in-person voting and an online voting system. A third option of voting by postal correspondence was also presented to the Chairpersons and Vice- chairpersons for their consideration. 2. These options have since been further elaborated in Appendix B of document CL 166/13 Arrangements for the 42nd Session of the Conference, for Council’s consideration at its 166th Session under item 13 of its Agenda. During discussions under item 13, Members not only sought further information on the practicalities of adopting one of the aforementioned options but also introduced a further alternative voting option: a hybrid of in-person and online voting. 3. In aiming to facilitate a more informed decision by Members, this note provides additional information on the previously identified voting options on which Members have already received preliminary information, and introduces the possibility of a hybrid voting option by combining in- person and online voting to create a hybrid option. 4. This Information Note further adds information on the conduct of a roll call vote through the Zoom system. Such a vote will be required at the beginning of the Conference for the endorsement of the special procedures outlined in Appendix A under item 3, Adoption of the Agenda and Arrangements for the Session, following their consideration by the General Committee of the Conference at its first meeting. -

The Political Effects of Electronic Voting in India

Technology and Protest: The Political Effects of Electronic Voting in India † Zuheir Desai∗ Alexander Lee April 7, 2019 Abstract Electronic voting technology is often proposed as translating voter intent to vote totals better than alternative systems such as paper ballots. We suggest that electronic voting machines (EVMs) can also alter vote choice, and, in particular, the way in which voters register anti- system sentiment. This paper examines the effects of the introduction of electronic voting machines in India, the world’s largest democracy, using a difference-in-differences methodol- ogy that takes advantage of the technology’s gradual introduction. We find that EVMs are as- sociated with dramatic declines in the incidence of invalid votes, and corresponding increases in vote for minor candidates. There is ambiguous evidence for EVMs decreasing turnout, no evidence for increases in rough proxies of voter error or fraud, and no evidence that machines with an auditable paper trail perform differently from other EVMs. The results highlight the interaction between voter technology and voter protest, and the substitutability of different types of protest voting. Word Count: 9995 ∗Department of Political Science, University of Rochester, Harkness Hall, Rochester, NY 14627. Email: [email protected]. †Department of Political Science, University of Rochester, Harkness Hall, Rochester, NY 14627. Email: alexan- [email protected]. 1 Introduction Social scientists have long been aware that voting technology may have important -

Medical Management of Biologic Casualties Handbook

USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Fourth Edition February 2001 U.S. ARMY MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES ¨ FORT DETRICK FREDERICK, MARYLAND 1 Sources of information: National Response Center 1-800-424-8802 or (for chem/bio hazards & terrorist events) 1-202-267-2675 National Domestic Preparedness Office: 1-202-324-9025 (for civilian use) Domestic Preparedness Chem/Bio Help line: 1-410-436-4484 or (Edgewood Ops Center - for military use) DSN 584-4484 USAMRIID Emergency Response Line: 1-888-872-7443 CDC'S Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Center: 1-770-488-7100 John's Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefense: 1-410-223-1667 (Civilian Biodefense Studies) An Adobe Acrobat Reader (pdf file) version and a Palm OS Electronic version of this Handbook can both be downloaded from the Internet at: http://www.usamriid.army.mil/education/bluebook.html 2 USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Fourth Edition February 2001 Editors: LTC Mark Kortepeter LTC George Christopher COL Ted Cieslak CDR Randall Culpepper CDR Robert Darling MAJ Julie Pavlin LTC John Rowe COL Kelly McKee, Jr. COL Edward Eitzen, Jr. Comments and suggestions are appreciated and should be addressed to: Operational Medicine Department Attn: MCMR-UIM-O U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) Fort Detrick, Maryland 21702-5011 3 PREFACE TO THE FOURTH EDITION The Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook, which has become affectionately known as the "Blue Book," has been enormously successful - far beyond our expectations. Since the first edition in 1993, the awareness of biological weapons in the United States has increased dramatically. -

Suppose You Want to Vote Strategically

DONALD SAARI Suppose You Want to Vote Strategically e honest. There have been times when you voted strate- To check, suppose five voters prefer the candidates Anita, Bgically to try to force a personally better election result; Bonnie, and Candy in that order, denoted by ABC, six oth- I have. The role of manipulative behavior received brief ers prefer CBA, and the last four prefer ACB. While it doesnt attention during the 2000 US Presidential Primary Season seem like anything can go wrong, lets check. when the Governor of Michigan failed on his promise to • By voting for one candidate, the commonly used plural- deliver his states Republican primary vote for George Bush. ity system, Anita wins with a 60% landslide; the ACB out- His excuse was that the winner, John McCain, strategically come has the 9:6:0 tally. attracted cross-over votes of independents and Democrats. • Bonnie failed to receive a single plurality vote, yet she McCains strategy was just the accepted behavior of en- wins when each voter votes for her top two candidates couraging supporters who can vote, to vote. But lets pursue where the BCA outcome has the 11:10:9 tally. this issue further; lets question whether the power of math- • Candy? She wins with the procedure offering 5 and 4 ematics can help identify when and how you can strategically points, respectively, to a voters first and second choices; alter the election outcome of your fraternity, sorority, social the CAB outcome has a 46: 45: 44 tally. group, or department to force a personally better conclusion. -

Nber Working Paper Series Valuing the Vote

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES VALUING THE VOTE: THE REDISTRIBUTION OF VOTING RIGHTS AND STATE FUNDS FOLLOWING THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT OF 1965 Elizabeth U. Cascio Ebonya L. Washington Working Paper 17776 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17776 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2012 We thank Bill Fischel, Alan Gerber, Claudia Goldin, Naomi Lamoreaux, Ethan Lewis, Sendhil Mullainathan, Gavin Wright and seminar participants at Dartmouth College, Hunter College and the University of Miami for helpful conversations in preparation of this draft. Cascio gratefully acknowledges research support from Dartmouth College, and Washington gratefully acknowledges research support from the National Science Foundation. All errors are our own. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Elizabeth U. Cascio and Ebonya L. Washington. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Valuing the Vote: The Redistribution of Voting Rights and State Funds Following the Voting Rights Act of 1965 Elizabeth U. Cascio and Ebonya L. Washington NBER Working Paper No. 17776 January 2012, Revised August 2012 JEL No. D72,H7,I2,J15,N32 ABSTRACT The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) has been called one of the most effective pieces of civil rights legislation in U.S. -

Randomocracy

Randomocracy A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Why the B.C. Citizens Assembly recommends the single transferable-vote system Jack MacDonald An Ipsos-Reid poll taken in February 2005 revealed that half of British Columbians had never heard of the upcoming referendum on electoral reform to take place on May 17, 2005, in conjunction with the provincial election. Randomocracy Of the half who had heard of it—and the even smaller percentage who said they had a good understanding of the B.C. Citizens Assembly’s recommendation to change to a single transferable-vote system (STV)—more than 66% said they intend to vote yes to STV. Randomocracy describes the process and explains the thinking that led to the Citizens Assembly’s recommendation that the voting system in British Columbia should be changed from first-past-the-post to a single transferable-vote system. Jack MacDonald was one of the 161 members of the B.C. Citizens Assembly on Electoral Reform. ISBN 0-9737829-0-0 NON-FICTION $8 CAN FCG Publications www.bcelectoralreform.ca RANDOMOCRACY A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Jack MacDonald FCG Publications Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Copyright © 2005 by Jack MacDonald All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2005 by FCG Publications FCG Publications 2010 Runnymede Ave Victoria, British Columbia Canada V8S 2V6 E-mail: [email protected] Includes bibliographical references. -

Americans and Russians Are Mostly Disinterested and Disengaged with Each Other

Americans and Russians Are Mostly Disinterested and Disengaged with Each Other Brendan Helm, Research Assistant, Public Opinion, Chicago Council on Global Affairs Arik Burakovsky, Assistant Director, Russia and Eurasia Program, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University Lily Wojtowicz, Research Associate, Public Opinion, Chicago Council on Global Affairs August 2019 The last few years have seen a substantial deterioration in relations between the United States and Russia. The international crisis over Ukraine, Russia’s interference in the 2016 US presidential election, and US sanctions against Russia have all contributed to the growing acrimony. Recent surveys conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and the Levada Analytical Center reveal that large majorities of both Russians and Americans now view their countries as rivals. But in the midst of heightened tensions between Moscow and Washington, how do regular citizens of each country view one another? A joint project conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, the Levada Analytical Center, and The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University shows that despite the perception of rivalry between their countries, Russians’ and Americans’ views on the people of the other country are more favorable. However, the survey results also show that Russians and Americans are not particularly curious about each other, they rarely follow news about one another, and the majority of each group has never met someone from the other. Nonetheless, self-reported interests from each side in arts and sciences suggest that there are non-political paths toward warmer relations. Key Findings • 68 percent of Americans view Russians either very or fairly positively, while 48 percent of Russians have those views of Americans. -

John Lewis' 'Good Trouble' Handbook

“THE RIGHT TO VOTE IS THE MOST POWERFUL NONVIOLENT TOOL WE HAVE IN A DEMOCRACY. I RISKED MY LIFE DEFENDING THAT RIGHT.” – Congressman John Lewis, John Lewis: Good Trouble Go to Map GOOD TROUBLE Congressman John Lewis’ life’s work has changed the very fabric of this country. Born in During the protest, John Lewis was hit on the head by a state trooper and suffered a the heart of the Jim Crow South, in the shadow of slavery, he saw the profound injustice fractured skull. On Bloody Sunday, Lewis risked his life for the right to vote and has since all around him and knew, from a young age, that he wanted to do something about it. By devoted his life to ensuring that every American has access to the ballot box. his late teens, he had joined the first Freedom Riders and later became the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), one of the groups responsible Unfortunately, Congressman Lewis’ work did not end with the Civil Rights era. In 2013, for organizing the 1963 March on Washington. On August 28, 1963, on the steps of the Voting Rights Act, for which he shed his blood, was effectively gutted by a Supreme the Lincoln Memorial, John Lewis gave his own rousing speech alongside some of the Court decision, Shelby County v. Holder. In the years since, voter suppression targeting greatest leaders of the civil rights movement, including Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. communities of color has significantly increased. But it was March 7, 1965, that etched Congressman Lewis into the American psyche. -

Spillover from High Profile Statewide Races Into Races

COLLECTIVE AND COMPONENT CONSTITUENCIES: SPILLOVER FROM HIGH PROFILE STATEWIDE RACES INTO RACES FOR THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES by GREGORY J. WOLF (Under the Direction of Jamie L. Carson) ABSTRACT It is widely known that turnout is substantially lower during midterm elections than it is in presidential elections. However, little research has addressed how turnout varies state by state. It is hypothesized that competitive high profile races increase turnout. Additionally, increases in turnout should impact races down the ballot through coattail effects. These hypotheses are tested in on- and off-year elections, expecting different results due to the presence of the presidential race at the top of the ticket in on-years. The results indicate competitive high profile races significantly increase turnout. Additionally, states with same-day voter registration have higher turnout rates than states that do not. Coattails are extended from the presidential race to House races in on-years and from Senate and gubernatorial races in off-years. Surprisingly, Senate races are the only types of races that see enhanced coattail effects when the race is competitive and they are negative in nature. INDEX WORDS: elections, congress, constituency, coattails, turnout COLLECTIVE AND COMPONENT CONSTITUENCIES: SPILLOVER FROM HIGH PROFILE STATEWIDE RACES INTO RACES FOR THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES by GREGORY J. WOLF B.A., The University of Pittsburgh, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Gregory J. Wolf All Rights Reserved COLLECTIVE AND COMPONENT CONSTITUENCIES: SPILLOVER FROM HIGH PROFILE STATEWIDE RACES INTO RACES FOR THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES by GREGORY J. -

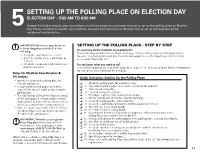

Setting up Polling Place on Election

ELECTION JUDGE/COORDINATOR HANDBOOK | GENERAL ELECTION 2020 CHAPTER 4 SETTING UP THE POLLING PLACE ON ELECTION DAY ELECTION DAY - 5:00 AM TO 6:00 AM Chapter 5 includes step-by-step instructions on all the procedures you need to know to set up the polling place on Election 5 Day. Please review this chapter very carefully. You only have one hour on Election Day to set up and organize all the equipment and materials. IMPORTANT! Before you open the doors SETTING UP THE POLLING PLACE - STEP BY STEP to the polling place, you MUST do the Do you have all the materials and equipment? following: Review the diagram of the ESC in Chapter 4 on page 20 to see where materials and equipment are • Set up the e-poll books (see step 8). located. For a listing of Election Day materials and equipment, see the Supply List (Form 21) in the • Begin the update of the e-poll books by sleeve of the door of the ESC. 5:15 am. • Check the equipment is labeled for your Do you know what you need to do? precinct and ward. First, read the quick overview of all the procedures, steps #1-18. Then, go on to the detailed instructions for each of the steps starting on the next page. Rules for Election Coordinators & All Judges Quick Overview: Setting Up the Polling Place • You MUST report to the polling place by 5:00 am and no later. ❏ 1. Check the polling place for a portable ramp. • Let poll watchers with proper credentials ❏ 2. -

Rhode Island Voter Information Handbook 2020 What’S in This Guide

Voter Information Handbook A Guide to State Referenda and Voting Procedures in Rhode Island General Election November 3, 2020 B A L LO T B A L L O T Nellie M. Gorbea Secretary of State Be Voter Ready! Message from the Secretary BALLOT Dear Rhode Island Voter: As your Secretary of State, it is my responsibility to make sure you are able to exercise your right to vote safely and securely. The social Preview a sample ballot distancing practices that help us prevent the spread of COVID-19 Your choice of candidates depends have forced us to change many aspects of our lives but we can still on where you live. be united in casting our votes. I am sending you this guide to make it Locally, there are 21 communities in easy for you to be informed, be engaged, and be a voter in 2020. which you will be asked to approve or reject municipal ballot questions. As a Rhode Island voter, you have the power to help move our great You can see a sample of your local state forward. You have three options for safely and securely casting ballot by visiting the online Voter a ballot this year and this guide offers more information on each of Information Center at vote.ri.gov. these voting methods. I urge you to make your voice heard. If you have applied for a mail ballot, be sure to fill out your ballot and return it as quickly as possible (see page 5). Ballot Your guide also contains information about a very important state question you will see on your ballot. -

None of the Above: Protest Voting in the World's Largest Democracy*

None Of The Above: Protest Voting in the World’sLargest Democracy Gergely Ujhelyi, Somdeep Chatterjee, and Andrea Szabóy February 29, 2020 Abstract Who are “protest voters” and do they affect elections? We study this question using the introduction of a pure protest option (“None Of The Above”) on Indian ballots. To infer individual behavior from administrative data, we borrow a model from the consumer demand literature in Industrial Organization. We find that in elections without NOTA, most protest voters simply abstain. Protest voters who turn out scatter their votes among many candidates and consequently have little impact on election results. From a policy perspective, NOTA may be an effective tool to increase political participation, and can attenuate the electoral impact of compulsory voting. We thank Sourav Bhattacharya, Francisco Cantú, Alessandra Casella, Aimee Chin, Julien Labonne, Arvind Magesan, Eric Mbakop, Suresh Naidu, Mike Ting, and especially Thomas Fujiwara for useful com- ments and suggestions. We also thank seminar participants at Oxford, Columbia, WUSTL, Calgary, the 2016 Wallis Institute Conference, the 2016 Banff Workshop in Empirical Microeconomics, NEUDC 2016, and the 2016 STATA Texas Empirical Microeconomics conference for comments. Thanks to seminar participants at the Indian Statistical Institute Kolkata, Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, and Public Choice Society 2015 for feedback on an earlier version. We gratefully acknowledge use of the Maxwell/Opuntia Cluster and support from the Center for Advanced Computing and Data Systems at the University of Houston. A previous version of the paper circulated under “‘None Of The Above’Votes in India and the Consumption Utility of Voting”(first version: November 1, 2015).