John Keats (1795-1821)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grave of John Keats Revisited

The Keats-Shelley Review ISSN: 0952-4142 (Print) 2042-1362 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yksr20 The Grave of John Keats Revisited Nicholas Stanley-Price To cite this article: Nicholas Stanley-Price (2019) The Grave of John Keats Revisited, The Keats- Shelley Review, 33:2, 175-193, DOI: 10.1080/09524142.2019.1659018 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09524142.2019.1659018 Published online: 18 Sep 2019. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yksr20 THE KEATS-SHELLEY REVIEW 2019, VOL. 33, NO. 2, 175–193 https://doi.org/10.1080/09524142.2019.1659018 ARTICLE The Grave of John Keats Revisited Nicholas Stanley-Price Advisory Committee, Non-Catholic Cemetery for Foreigners, Rome ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Many visitors in the nineteenth century to the grave of John Keats in John Keats; Rome; Rome thought it ‘neglected’ or ‘solitary’ and ‘unshaded’.Today’scritics Protestant cemetery; poet’s often characterize the grave as ‘marginal’, both literally and metaphori- grave; Percy Bysshe Shelley; cally, while ignoring the city authorities’ proposal to demolish it in the Joseph Severn; Romantics 1880s. An analysis of the grave’s original setting and its subsequent renovations suggests instead that it enjoyed a privileged position. Historical descriptions, when considered together with visitors’ accounts – avaluablesourceifusedcritically– and little-known artists’ depictions of Keats’s grave prompt a re-assessment of ideas of its ‘marginality’ and ‘neglect’ in the nineteenth century. The grave lies quite alone, and is evidently much neglected. -

![1875, June 29]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4783/1875-june-29-44783.webp)

1875, June 29]

[1875, June 29] [From: Pickering, B.M.]1 [To: Lord Alfred Tennyson] 196 Piccadilly W June 29 1875 Sir Several years ago when the books of the late Sir C.W. Dilke2 were sold by auction I purchased a volume containing “The Lover’s Tale”3[.] I unfortunately lent it to Mr. Richard Herne Shepherd4 he expressing a great desire to read it and I at the time believing him a trustworthy person[.] Soon after this I found that he had dishonestly printed this poem from a transcript he had taken from my copy. On that occasion (by paying the printer, when he pretended he could not pay unless he sold copies) I induced him to suppress the copies and he handed me his transcript [Page 2] but either he had a duplicate transcript or a copy of the printed type for I have just discovered that he has a second time put the poem into type[.] Mr. Locker5 mentioned to me that an advertisement 1 Basil Montagu Pickering (1835-1878) was a publisher who specialized in rare books and first editions of nineteenth-century poets (see the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [ODNB]). Pickering published Tennysoniana in 1866. 2 Charles Wentworth Dilke (1789-1864) was a newspaper editor and writer who, at various stages in his career, contributed to or led such publications as Retrospective Review, London Magazine, The Athenaeum (of which Dilke became editor in 1831), and the Daily News. Dilke had many friends and acquaintances among the literary elite of the country, including John Keats, Leigh Hunt, George Eliot, and Percy Shelley (see ODNB). -

Victoria Albert &Art & Love Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and Their Relations with Artists

Victoria Albert &Art & Love Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and their relations with artists Vanessa Remington Essays from two Study Days held at the National Gallery, London, on 5 and 6 June 2010. Edited by Susanna Avery-Quash Design by Tom Keates at Mick Keates Design Published by Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2012. Royal Collection Enterprises Limited St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1JR www.royalcollection.org ISBN 978 1905686 75 9 First published online 23/04/2012 This publication may be downloaded and printed either in its entirety or as individual chapters. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for non-commercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses please contact Royal Collection Enterprises Limited. www.royalcollection.org.uk Victoria Albert &Art & Love Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and their relations with artists Vanessa Remington Victoria and Albert: Art and Love, a recent exhibition at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, was the first to concentrate on the nature and range of the artistic patronage of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. This paper is intended to extend this focus to an area which has not been explored in depth, namely the personal relations of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and the artists who served them at court. Drawing on the wide range of primary material on the subject in the Royal Archive, this paper will explore the nature of that relationship. It will attempt to show how Queen Victoria and Prince Albert operated as patrons, how much discretion they gave to the artists who worked for them, and the extent to which they intervened in the creative process. -

Unlocking Eastlake Unlocking Eastlake

ng E nlocki astlak U e CREATED BY THE YOUNG EXPLAINERS OF PLYMOUTH CITY MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY No. 1. ] SEPTEMBER 22 - DECEMBER 15, 2012. [ One Penny. A STROKE OF GENIUS. UNLOCKING EASTLAKE UNLOCKING EASTLAKE It may be because of his reserved nature that Staff at the City Museum and Art Gallery are organising a range of events connected to the Eastlake is not remembered as much as he exhibition, including lunchtime talks and family-friendly holiday workshops. INTRODUCING deserves to be. Apart from securing more Visit www.plymouth.gov.uk/museumeastlake to stay up to date with what’s on offer! than 150 paintings for the nation, Eastlake was a key figure in helping the public gain like to i uld ntro a better understanding of the history of wo d uc WALKING TRAILS e e EASTLAKE western art. Through detailed catalogues, W THE simpler ways of picture display, and the Thursday 20th September 2012: : BRITISH ART’S PUBLIC SERVANT introduction of labels enabling free access to Grand Art History Freshers Tour information, Eastlake gave the us public art. YOUNG EXPLAINERS A chance for Art History Freshers to make friends as well as see what lmost 150 years after his Article: Laura Hughes the Museum and the Young Explainers death, the name of Sir Charles Children’s Actities / Map: Joanne Lees have to offer. The tour will focus on UNLOCKING EASTLAKE’S PLYMOUTH Eastlake has failed to live up to Editor: Charlotte Slater Eastlake, Napoleon and Plymouth. the celebrity of his legacy. Designer: Sarah Stagg A Illustrator (front): Alex Hancock Saturday 3rd November 2012: Even in his hometown of Plymouth, blank faces During Eastlake’s lifetime his home city Illustrator (inside): Abi Hodgson Lorente Eastlake’s Plymouth: usually meet the question: “Who is Sir Charles of Plymouth dramatically altered as it A Family Adventure Through Time Eastlake?” Yet this cultural heavyweight was transformed itself from an ancient dockland Alice Knight Starting at the Museum with interactive acknowledged to be one of the ablest men of to a modern 19th century metropolis. -

Eastlake's Scholarly and Artistic Achievements Wednesday 10

Eastlake's Scholarly and Artistic Achievements Wednesday 10 October 2012 Lizzie Hill & Laura Hughes Overview I will begin this Art Bite with a quotation from A Century of British Painters by Samuel and Richard Redgrave, who refer to Eastlake as one of "a few exceptional painters who have served the art they love better by their lives than their brush" . This observation is in keeping with the norm of contemporary views in which Eastlake is first and foremost seen as an art historian and collector. However, as a man who began his career as a painter, it seems it would be interesting to explore both of these aspects of his life. Therefore, this Art Bite will be examining the validity of this critique by evaluating Eastlake's artistic outputs and scholarly achievements, and putting these two aspects of his life in direct relation to each other. By doing this, the aim behind this Art Bite is to uncover the fundamental reason behind Eastlake's contemporary and historical reputation, and ultimately to answer; - What proved to be Eastlake's best weapon in entering the Art Historical canon: his brain or his brush? Introduction So, who was Sir Charles Lock Eastlake? To properly be able to compare his reputation as an art historian versus being a painter himself, we need to know the basic facts about the man. A very brief overview is that Eastlake was born in Plymouth in 1793 and from an early age was determined to be a painter. He was the first student of the notable artist Benjamin Haydon in January 1809 and received tuition from the Royal Academy schools from late 1809. -

Notes and References

Notes and References Prologue: Food Security and the Literary Imagination 1. Jane Austen, Letter to Cassandra Austen, 23 Hans Place, 23–24 August 1814, in Jane Austen (1995), Jane Austen’s Letters, ed. Deirdre Le Faye, 4th edn (Oxford University Press), pp. 281–4 (p. 238). 1 Food Matters 1. Cited in Frank Dikötter (2010), Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–62 (London: Bloomsbury), unpaginated preliminary pages. 2. Harry Thompson (2011), Peter Cook: A Biography (London: Hachette, 2011; orig. pub. Hodder & Stoughton, 1997), p. 47. 3. Francisco Goya y Lucientes, Saturn Devouring his Son (1819–23), 1.43 m x 81 cm, Museo Nacional Del Prado, Madrid, Spain; Hannibal Lecter first appeared in Thomas Harris’s novel Red Dragon (1981). 4. Maggie Kilgour (1990), From Communion to Cannibalism: An Anatomy of Metaphors of Incorporation (Princeton University Press). 5. See, for example, Bonnie J. W. Martin, Jeri A. Logemann, Reza Shaker and Wylie J. Dodds (1994), ‘Coordination Between Respiration and Swallowing: Respiratory Phase Relationships and Temporal Integration,’ Journal of Applied Physiology 76: 714–23. 6. Suzanne Collins (2009), Catching Fire (New York: Scholastic Press), p. 22. The political use of food and hunger in the Hunger Games trilogy is discussed further in the Epilogue. 7. Colin Tudge (2004), So Shall We Reap: What’s Gone Wrong with the World’s Food – and How to Fix It (London: Penguin; orig. pub. Allen Lane, 2003), p. 34. 8. Daniel Quinn (2009), Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit (New York: Random House; orig. pub. Bantam, 1992). -

Some Remarks on Keats and His Friends

SOME REMARKS ON KEATS AND HIS FRIENDS By SIR ROBERT ARMSTRONG-JONES, C.B.E., M.D., D.L. LONDON, ENGLAND HE function of poetry is to of short stature, with a long and oval express and embody beautiful face, arresting features even to the and elevated ideas in language casual passer-by, every lineament that can stir the emotions and strongly cut and delicately alive. His Tit has an orderly, methodical wayhead of was well shaped, his eyes were presenting its creations, generally with dark, sensitive, large and glowing. His metrical and rhythmic periods. Ebe hair was golden brown, thick and curly. poet is a creator, who begins with the Severn said his eyes were like the hazel concrete and leads on to abstract eyes of a wild gipsy maid. Haydon said thought, so as to arouse pleasurable he had an eye that had an inward look sentiments in combination with a feel perfectly divine like a Delphic priestess ing of power, wonder, curiosity, respect, that had visions. affection, exaltation and love or some He was born on October 31, 1795, in times of envy and hatred. a posting-house, the Swan and Hoop, Probably no poet has ever kindled now 85 Moorgate, London; opposite a deeper feeling of pity and sympathy the entrance to Finsbury Circus, and for than Keats, mingled as this has been this accident he was taunted as the with a compelling admiration for his “cockney” poet as contrasted with the brilliant but short life’s work, shorter “Lakists.” His father, Thomas Keats, than that of any noted English poet. -

John Keats 1 John Keats

John Keats 1 John Keats John Keats Portrait of John Keats by William Hilton. National Portrait Gallery, London Born 31 October 1795 Moorgate, London, England Died 23 February 1821 (aged 25) Rome, Italy Occupation Poet Alma mater King's College London Literary movement Romanticism John Keats (/ˈkiːts/; 31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English Romantic poet. He was one of the main figures of the second generation of Romantic poets along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, despite his work only having been in publication for four years before his death.[1] Although his poems were not generally well received by critics during his life, his reputation grew after his death, so that by the end of the 19th century he had become one of the most beloved of all English poets. He had a significant influence on a diverse range of poets and writers. Jorge Luis Borges stated that his first encounter with Keats was the most significant literary experience of his life.[2] The poetry of Keats is characterised by sensual imagery, most notably in the series of odes. Today his poems and letters are some of the most popular and most analysed in English literature. Biography Early life John Keats was born in Moorgate, London, on 31 October 1795, to Thomas and Frances Jennings Keats. There is no clear evidence of his exact birthplace.[3] Although Keats and his family seem to have marked his birthday on 29 October, baptism records give the date as the 31st.[4] He was the eldest of four surviving children; his younger siblings were George (1797–1841), Thomas (1799–1818), and Frances Mary "Fanny" (1803–1889) who eventually married Spanish author Valentín Llanos Gutiérrez.[5] Another son was lost in infancy. -

THE POLITICS of CATASTROPHE in the ART of JOHN MARTIN, FRANCIS DANBY, and DAVID ROBERTS by Christopher J

APOCALYPTIC PROGRESS: THE POLITICS OF CATASTROPHE IN THE ART OF JOHN MARTIN, FRANCIS DANBY, AND DAVID ROBERTS By Christopher James Coltrin A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History of Art) in the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Susan L. Siegfried, Chair Professor Alexander D. Potts Associate Professor Howard G. Lay Associate Professor Lucy Hartley ©Christopher James Coltrin 2011 For Elizabeth ii Acknowledgements This dissertation represents the culmination of hundreds of people and thousands of hours spent on my behalf throughout the course of my life. From the individuals who provided the initial seeds of inspiration that fostered my general love of learning, to the scholars who helped with the very specific job of crafting of my argument, I have been the fortunate recipient of many gifts of goodness. In retrospect, it would be both inaccurate and arrogant for me to claim anything more than a minor role in producing this dissertation. Despite the cliché, the individuals that I am most deeply indebted to are my two devoted parents. Both my mother and father spent the majority of their lives setting aside their personal interests to satisfy those of their children. The love, stability, and support that I received from them as a child, and that I continue to receive today, have always been unconditional. When I chose to pursue academic interests that seemingly lead into professional oblivion, I probably should have questioned what my parents would think about my choice, but I never did. Not because their opinions didn‟t matter to me, but because I knew that they would support me regardless. -

Albert Moore

MA Dissertation Laurence Shafe Albert Moore and the Science of Beauty June 2008 Supervisor: Caroline Arscott Word count: 10,448 (excluding footnotes and bibliography) Abstract Albert Moore and the Science of Beauty This dissertation investigates the work of Albert Moore (1841-1893) and is based on his sketches at the Victoria and Albert and British Museums and his working principles described in his biography by Alfred Lys Baldry (1858-1939). These working principles were based in part on the work of the interior decorator and theoretician David Ramsey Hay (1798-1866) whose ideas were described in his book Science of Beauty and incorporated in the training given by the Schools of Design that Moore attended. Hay’s work was related to the work of the palaeontologist Richard Owen (1804-1892) who, in 1848, proposed a theory of an archetype based on ideal Platonic forms, and in 1852 Hay described mathematical rules of beauty for the human figure based on the proportions of classical works of art thought to represent the Platonic idea of beauty. Moore’s classical figures referenced this aesthetic classical ideal rather than the conventional heroic narrative of early nineteenth-century Neoclassical works. Moore was also influenced by the International Exhibition at South Kensington in 1862 which presented art and science as a single experience, introduced Japanese art to a wider audience and positioned the classicized nude as an example of modernity. It argues that Moore, and to some extent the other members of the Aesthetic Movement, were influenced not only by French aesthetic ideas but also by the Neoclassical theories of Hay and others and their scientific approach to achieving beauty through the use of mathematical proportions based on musical intervals, the Neoplatonic ideas of beauty that parallel Owen’s work on the archetype and Japanese art seen at the International Exhibition of 1862. -

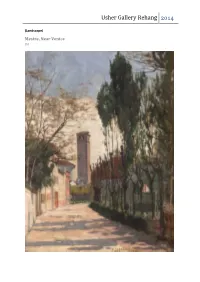

Usher Gallery Rehang 2014

Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Landscape) Mestre, Near Venice Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Landscape) Church of St. Maria Della Salute, c.1885 Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Landscape) Venice Oil (Landscape) Venice Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Still Life) Flowers in a Persian Bottle Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Still Life) Daffodils Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Still Life) Garden Flowers Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 Michiel Jansz. van Miereveldt – (1 May 1567 – 27 June 1641) About The artist, Michiel Jansz. van Miereveldt was born in the Delft and was one of the most successful Dutch portraitists of the 17th century. His works are predominantly head and shoulder portraits, often against a monochrome background. The viewer is drawn towards the sitter’s face by light accents revealed by clothing. After his initial training, Mierevelt quickly turned to portraiture. He gained success in this medium, becoming official painter of the court and gaining many commissions from the wealthy citizens of Delft, other Dutch nobles and visiting foreign dignitaries. His portraits display his characteristic dry manner of painting, evident in this work where the pigment has been applied without much oil. The elaborate lace collar and slashed doublet are reminiscent of clothes that appear in Frans Hals's work of the same period. Work in The Usher Gallery (Portrait) Maria Van Wassenaer Hanecops Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 Mary Henrietta Dering Curtois – (1854 - 6 October 1928) About Mary Henrietta Dering Curtois was born at the Longhills, Branston, in 1854 and was the eldest daughter of the late Rev Atwill Curtois (for 21 years Rector of Branston and the fifth of the family to be rector there), and a brother of the Rev Algernon Curtois of Lincoln. -

Vebraalto.Com

164 Westfield Plymouth, PL7 2EH Price £195,000 Freehold 164 Westfield, Plymouth, PL7 2EH Price £195,000 Freehold Cross Keys Estates are delighted to present for sale this immaculately presented three bedroom end of terrace home situated within the popular residential district of Plympton. Having undergone a recent program of refurbishment this wonderful home now offers newly decorated accommodation comprising entrance hallway, fitted kitchen, sitting room, separate dining room, utility, downstairs WC, three ample upstairs bedrooms and a shower room. Other benefits include a sheltered patio area, rear garden and access to a large single garage with parking directly in front. The property boasts a new kitchen and upgraded boiler and is in situated within a quiet cul de sac setting with a pedestrianized area to the front. Offered to market with no onward chain, this property would make a fantastic first home, investment or family property and an early internal viewing is highly recommended. • End Terrace Family Home • Popular Residential Location • Close To Local Amenities • Newly Refurbished Home • Early Viewing Essential • No Onward Chain • Front & Rear Gardens • Large Single Garage & Parking • PVCu DG & GCH • EPC - D Plympton Plympton was the site of an important priory in the early 12th century. The members were Augustinian canons and the priory soon became the second richest monastic house in Devon. The gatehouse of the priory is still in existence. The town was the birthplace and early residence of the painter Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds was Mayor of Plympton, as well as first president of the Royal Academy of Art. His father was headmaster of Plympton Grammar School which itself is an attractive historic building in the centre of the town, now known as Hele's Secondary School.