Sustainability in Mega-Events: Beyond Qatar 2022

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qatar 2022 Overall En

Qatar Population Capital city Official language Currency 2.8 million Doha Arabic Qatari riyal (English is widely used) Before the discovery of oil in Home of Al Jazeera and beIN 1940, Qatar’s economy focused Media Networks, Qatar Airways on fishing and pearl hunting and Aspire Academy Qatar has the third biggest Qatar Sports Investments owns natural gas reserves in the world Paris Saint-Germain Football Club delivery of a carbon-neutral tournament in 2022. Under the agreement, the Global Carbon Trust (GCT), part of GORD, will Qatar 2022 – Key Facts develop assessment standards to measure carbon reduction, work with organisations across Qatar and the region to implement carbon reduction projects, and issue carbon credits which offset emissions related to Qatar 2022. The FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ will kick off on 21 November 2022. Here are some key facts about the tournament. Should you require further information, visit qatar2022.qa or contact the Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy’s Tournament sites are designed, constructed and operated to limit environmental impacts – in line with the requirements Media Team, [email protected]. of the Global Sustainability Assessment System (GSAS). A total of nine GSAS certifications have been awarded across three stadiums to date: 21 November 2022 – 18 December 2022 The tournament will take place over 28 days, with the final being held on 18 December 2022, which will be the 15th Qatar National Day. Eight stadiums Khalifa International Stadium was inaugurated following an extensive redevelopment on 19 May 2017. Al Janoub Stadium was inaugurated on 16 May 2019 when it hosted the Amir Cup final. -

Qnbfs.Com.Qa [email protected] [email protected]

` QSE Intra-Day Movement Market Indicators 04 May 20 03 May 20 %Chg. Value Traded (QR mn) 439.1 401.1 9.5 9,300 Exch. Market Cap. (QR mn) 524,628.9 522,433.1 0.4 Volume (mn) 182.1 168.8 7.8 9,250 Number of Transactions 10,151 10,143 0.1 Companies Traded 46 44 4.5 9,200 Market Breadth 24:14 30:9 – 9,150 Market Indices Close 1D% WTD% YTD% TTM P/E Total Return 17,786.80 0.4 4.3 (7.3) 14.6 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 All Share Index 2,867.99 0.5 3.7 (7.5) 15.3 Banks 3,999.53 0.6 2.6 (5.2) 13.1 Industrials 2,628.79 0.5 7.1 (10.3) 20.9 Qatar Commentary Transportation 2,653.96 0.0 3.8 3.9 12.9 The QE Index rose 0.4% to close at 9,252.1. Gains were led by the Consumer Goods & Real Estate 1,401.96 (0.1) 2.7 (10.4) 13.9 Services and Banks & Financial Services indices, gaining 1.1% and 0.6%, Insurance 2,008.34 (0.7) (0.7) (26.6) 33.7 respectively. Top gainers were Doha Insurance Group and Qatari German Company Telecoms 890.29 (0.7) 7.4 (0.5) 15.0 for Medical Devices, rising 6.3% and 5.4%, respectively. Among the top losers, Qatar Consumer 7,450.84 1.1 5.3 (13.8) 19.0 General Insurance & Reinsurance Co. -

The Dark Side of Migration: Spotlight on Qatar's Construction Sector Ahead of the World Cup

THE DARK SIDE OF MIGRATION: SPOTLIGHT ON QATAR'S CONSTRUCTION SECTOR AHEAD OF THE WORLD CUP Amnesty International Publications First published in 2013 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2013 Index: MDE 22/010/2013 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom [ISBN:] [ISSN:] All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Doha skyline © Lubaib Gazir Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership -

Press Release

press release AS&P – Albert Speer & Partner GmbH Architekten, Planer architects, planners FIFA Inspection Visit in Qatar – Designs for all Stadiums now Going Public Hedderichstraße 108-110 60596 Frankfurt am Main Postfach 70 09 63 D-60559 Frankfurt am Main 2010-09-16 Telefon: +49 (0) 69-60 50 11-0 From 14-16 Sept., 2010 a delegation from FIFA will visit Qatar on the inspection visit Telefax: +49 (0) 69-60 50 11-500 for the FIFA World Cup 2022TM. All 11 candidate countries officially submitted their [email protected] applications on 14 May to the FIFA, in July the latter started its evaluation visits to the various countries. Geschäftsführer: In Qatar, the FIFA delegation will be able to study the potential to realize an extremely Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Albert Speer compact competition concept. Since all the stadiums will be within one hour’s drive of Dipl.-Ing. Gerhard Brand the FIFA headquarters, fans will be able to enjoy attending more than one game a day. Dipl.-Ing. Friedbert Greif A new and effective metro network of 320km in total length will be ready and waiting to move them around in 2021. All the stadiums are accessible from the Qatar expres- sway system and spectators will therefore have absolutely no difficulty in traveling to AS&P Architecture Consulting Co. and from the stadiums; indeed, some of the stadiums can even be reached by water Ltd. taxi. And not only the fans will benefit from this super-compact concept, but the teams, 841 Yan An Road (M) too – who will be able to remain in one and the same base camp for the duration of the Room 1102 entire tournament. -

Education City and Ahmad Bin Ali Stadiums to Stage FIFA Event

Sport TUESDAY 19 JANUARY 2021 IndiaInd eye fairytale Test win as Australia ffretre over paceman Mitchell Starc OneOne thing I know about Mitchell is he’s tough. He has played throughthro some injuries before and got the job done so he’ll be hopefullyhope good to go tomorrow. Australia's Steve Smith Sport |09 NBA RESULTS: San Antonio 103, Houston 91; Brooklyn 122, Orlando 115; Toronto 116, Charlotte 113; Memphis 106, Philadelphia 104 Education City Stadium Voting process begins for QFA Awards THE PENINSULA – DOHA The Board of Trustees of the Qatar Football Association (QFA) Award has announced the start of first phase of voting for the Best Awards for the 2020-21 season. The opening phase of the FIFA Club World Cup 2020 to kick off on February 4 voting process includes the first leg of QNB Stars League, where the Best Player and Best Under-23 Player are voted for. Education City and Ahmad Bin Ali Voting forms (55 question- naires and shortlists of the most prominent players in both categories during the league’s first leg) have been Stadiums to stage FIFA event sent out to the participants in the voting process, namely: QNB Stars League team THE PENINSULA – DOHA stage the first match on February coaches, Qatar national team 4 at 5:00pm Qatar time, and the coach, Qatar Under-23 team Following confirmation that FIFA Club World Cup champions Visa Presale offers exclusive coach, Team managers, Media Auckland City FC will be unable will be crowned at Education City representatives, Represent- to participate in the FIFA Club Stadium on February 11 as the ative of QFA, Representative World Cup 2020, FIFA has final kicks off at 9.00pm. -

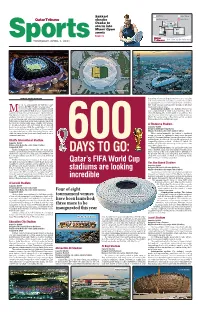

Days to Go: Lation

Sakkari QatarTribune Qatar_Tribune shocks QatarTribuneChannel qatar_tribune Osaka to storm into Miami Open semis PAGE 15 THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 2021 Ahmad Bin Ali Stadium Al Janoub Stadium Khalifa International Stadium TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK hospitality. This uniquely Qatari stadium comes complete DOHA with a state-of-the-art retractable roof and is surrounded by 400,000m² of green spaces for the local community. ARCH 31, 2021 marked the 600-day count- The venue will host nine matches through to the semi- down to the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™. finals stage of Qatar 2022. THE first WorldC up in the Middle East and Construction update: The stadium structure has Arab world will kick off on 21 November and been completed and is ready to host matches. This in- Mconclude 28 days later on 18 December – Qatar National cludes the laying of the stadium pitch in record time. This Day. Qatar’s infrastructure plans are well advanced. Four year, the venue achieved a high sustainability rating from stadiums have been inaugurated, the new metro system GSAS. The surrounding Al Bayt Park opened on Qatar is up and running, and a host of expressways have been National Sports Day in February 2020. built. Here’s a closer look at the eight stadiums which will host matches during Qatar 2022. Khalifa International, Al Janoub, Education City and Ahmad Bin Ali have all Al Thumama Stadium hosted major matches, while the construction of Al Bayt Capacity: 40,000 has been completed. Along with Al Bayt, Al Thumama and Designer: Arab Engineering Bureau Ras Abu Aboud are set to be inaugurated during 2021, Distance from Doha city centre: 12km (7 miles) while the venue for the Qatar 2022 final, Lusail, is set to With a design inspired by the ‘gahfiya’, a traditional open early next year. -

GIIGNL Annual Report Profile

The LNG industry GIIGNL Annual Report Profile Acknowledgements Profile We wish to thank all member companies for their contribution to the report and the GIIGNL is a non-profit organisation whose objective following international experts for their is to promote the development of activities related to comments and suggestions: LNG: purchasing, importing, processing, transportation, • Cybele Henriquez – Cheniere Energy handling, regasification and its various uses. • Najla Jamoussi – Cheniere Energy • Callum Bennett – Clarksons The Group constitutes a forum for exchange of • Laurent Hamou – Elengy information and experience among its 88 members in • Jacques Rottenberg – Elengy order to enhance the safety, reliability, efficiency and • María Ángeles de Vicente – Enagás sustainability of LNG import activities and in particular • Paul-Emmanuel Decroës – Engie the operation of LNG import terminals. • Oliver Simpson – Excelerate Energy • Andy Flower – Flower LNG • Magnus Koren – Höegh LNG • Mariana Ortiz – Naturgy Energy Group • Birthe van Vliet – Shell • Mika Iseki – Tokyo Gas • Yohei Hukins – Tokyo Gas • Donna DeWick – Total • Emmanuelle Viton – Total • Xinyi Zhang – Total © GIIGNL - International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers All data and maps provided in this publication are for information purposes and shall be treated as indicative only. Under no circumstances shall they be regarded as data or maps intended for commercial use. Reproduction of the contents of this publication in any manner whatsoever is prohibited without prior -

Five Key Facts About Education City Stadium I See You in 2022

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 06/17/2020 5:58:05 PM Education City Stadium Launch Pitches Architecture/Design Reporters Subject line: Diamond in the Desert: Architectural marvel now complete Hi, The 40,000-capacity football arena, dubbed Diamond in the Desert, is now complete. This is the third tournament venue for the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 in Doha, Qatar. The stadium sits in the heart of Qatar Foundation's Education City, and has been built for use long after the World Cup ends. I thought you might be interested in spotlighting this architectural marvel that skillfully blends design and sustainability. It blends both beautiful architecture with innovative systems built to sustainably cool spectators and athletes in a hot desert climate. Geometric patterns on the stadium's facade appear to change color as the sun moves during the day, and the stadium has received the prestigious five-star rating from the Global Sustainability Assessment System (GSAS), making it one of the most sustainable venues for Qatar 2022. Other notable features include: • Designed by Mark Fenwick of Fenwick Iribarren Architects in Madrid, Spain, the stadium was designed to provide intense and potent effect for soccer fans. The roof is designed to help acoustics bounce on to the pitch, heightening the excitement of the games. • Designed within Qatar Foundation's footprint, the Education City stadium takes advantage of the climate to maintain a cool temperature inside the structure. The stadium incorporates multiple passive design elements reducing the overall energy consumption. • The shape of the stadium stops wind from getting into the venue for more effective cooling in the desert heat. -

Qatar-An-Emerging-Sports-Destination

TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE CEO AND BOARD MEMBER 5 KEY HIGHLIGHTS 7 CHAPTER 1: SPORTS IN QATAR 12 CHAPTER 2: SPORTS EVENTS 16 CHAPTER 3: 2022 FIFA WORLD CUP 21 CHAPTER 4: BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES 23 CHAPTER 5: SPORTS ENTITIES 29 CHAPTER 6: SPORTS INFRASTRUCTURE 37 CHAPTER 7: ABOUT THE QFC 42 KEY CONTACTS FOR SETTING UP IN THE QFC 46 APPENDIX 47 GLOSSARY 69 2 QATAR – AN EMERGING SPORTS DESTINATION: BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES 3 MESSAGE FROM THE CEO AND BOARD MEMBER Over the last decade, Qatar has gained an enviable reputation for its ability to hold world-class sporting events to the very highest standards, beginning in 2006 when the nation successfully hosted the Asian Games. In the intervening years, Qatar has grown into a major sporting hub, attracting international events such as the World Indoor Athletics Championships, the Asian Football Confederation Asian Cup, the 24th Men’s Handball World Championship, and the AIBA World Boxing Championship. With ever-more prestigious international events on the horizon, including the 2022 FIFA World Cup and the 2023 FINA World Championships, sport continues to play a pivotal role in and around Qatar, while greatly contributing to the country’s infrastructural development. The sports sector delivers many local and international benefits, which are allowing Qatar to strengthen relations with nations worldwide. And, in an effort to consolidate the country’s commitment to the sporting industry, a Sports Sector Strategy (SSS) was developed as one of the 14-sector strategies within the Qatar National Vision 2030. Given the strategic importance of sports to Qatar’s economy, the Qatar Financial Centre (QFC) developed for the very first time since its establishment this study as an insightful overview into the nation’s sporting ecosystem, highlighting its flourishing business opportunities. -

How Can Qatar Land Its Sporting Strategy?

SPECIAL REPORT | QATAR Up in the air: how can Qatar land its sporting strategy? Qatar is well on the way to becoming an international sports superpower. An investor in a string of global properties and an increasingly prominent host of major events, the tiny state is already preparing to stage the 2022 Fifa World Cup, amidst a swell of controversy and no little bewilderment. SportsPro, with the help of experts from a variety of fields, looks at the five keyquestions facing Qatar as it prepares for its most important decade. By David Cushnan and James Emmett How do you intend to build and use mass of just over 11,500 square kilometres, and no little bewilderment. There may ten to 12 World Cup stadiums in a with the vast majority located in and be few real doubts about Qatar’s ability country of 1.9 million people? around the capital city, Doha, on the east to build the ten to 12 stadiums required coast. The decision to award Qatar the \ In 2022, Qatar will stage the most tournament, following a Fifa Executive \ compact Fifa World Cup in history. Just 1.9 Committee vote in December 2010, has presents a far greater challenge for local million people live in a state with a land \ organisers and Qatar’s rulers. 94 | www.sportspromedia.com SportsPro Magazine | 95 SPECIAL REPORT | QATAR Qatar’s 2022 Fifa World Cup stadium plan (as per 2010 bid) Al-Gharafa Stadium Khalifa International Stadium Location: Al- Location: Al- Rayyan Rayyan Capacity: 44,740 Capacity: 68,030 Cost: US$135 Cost: US$71 million million Matches: Group Matches: Group matches, -

Spaces of Mega Sporting Events Versus Public Spaces: Qatar 2022 World Cup and the City of Doha

The Journal of Public Space ISSN 2206-9658 2019 | Vol. 4 n. 2 https://www.journalpublicspace.org Spaces of Mega Sporting Events versus Public Spaces: Qatar 2022 World Cup and the City of Doha Simona Azzali James Cook University, College of Science and Engineering, Singapore [email protected] Abstract In the last decades, many emerging countries have been staging mega sporting events more and more frequently. Among those nations, Qatar stands out for being the first Arab country to host a FIFA World Cup. With the rationale of diversifying its economy and promoting itself as a tourist destination, Doha, its capital city, has recently staged many international events and is literally under construction, undergoing important changes in terms of transportation, infrastructure, and sports facilities. While hosting cities and organising committees often promote the supposed benefits of a mega event, experience shows an opposite trend: outcomes from staging major events are mostly harmful, and their effects are planned to last only for a short time. When it comes to sporting events sites, stadiums, and their precincts, they usually become under-used and very costly to maintain in a very short time, and their precincts are completely abandoned. THE JOURNAL OF PUBLIC SPACE THE JOURNAL What will be the destiny of the 2022 World Cup stadiums and infrastructure? How can this event be leveraged as a momentum of experimentation and sustainable growth of its capital city, Doha? Is it possible to transform the Cup’s stadiums and precincts into liveable, enjoyable and well-integrated public spaces and neighbourhoods? This work focuses on the city of Doha, which hosted the 2006 Asian Games and will host the 2022 FIFA World Cup and aims to identify strategies to plan and maximise the post- event use of event sites and venues, more specifically stadiums, to generate more liveable and sustainable public spaces. -

Sustainability Strategy 1

Sustainability Strategy 1 FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022TM Sustainability strategy 2 FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ Sustainability Strategy 3 Contents Foreword by the FIFA Secretary General 4 Foreword by the Chairman of the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 LLC and Secretary General of the Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy 6 Introduction 8 The strategy at a glance 18 Human pillar 24 Social pillar 40 Economic pillar 56 Environmental pillar 64 Governance pillar 78 Alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals 88 Annexe 1: Glossary 94 Annexe 2: Material topic definitions and boundaries 98 Annexe 3: Salient human rights issues covered by the strategy 103 Annexe 4: FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ Sustainability Policy 106 4 FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ Sustainability Strategy 5 Foreword © Getty Images by the FIFA Secretary General Sport, and football in particular, has a unique capacity The implementation of the FIFA World Cup Qatar We are also committed to delivering an inclusive As a former long-serving UN official, I firmly believe to inspire and spark the passion of millions of fans 2022™ Sustainability Strategy will be a central FIFA World Cup 2022™ tournament experience that in the power of sport, and of football in particular, around the globe. As the governing body of element of our work to realise these commitments is welcoming, safe and accessible to all participants, to serve as an enabler for the SDGs, and I am football, we at FIFA have both a responsibility and over the course of the next three years as we attendees and communities in Qatar and around personally committed to seeing FIFA take a leading a unique opportunity to harness the power of the prepare to proudly host the FIFA World Cup™ in the world.