From Nine to Five to the Devil Wears Prada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association for Consumer Research

ASSOCIATION FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH Labovitz School of Business & Economics, University of Minnesota Duluth, 11 E. Superior Street, Suite 210, Duluth, MN 55802 Masculine Fashion: Prescription and Description Susan Kaiser, University of California, Davis, USA Janet Hethorn, University of Delaware, USA Ryan Looysen, University of California, Davis, USA Daniel Claro, University of Delaware, USA The presentation will focus on the interplay among prescription, description, and inscription in social constructions of masculine fashion. Based upon (a) archival, critical discourse analyses of men’s magazines (e.g., Esquire, GQ, Details) and (b) interviews and surveys with U.S. male consumers, we explore the complex relationship between institutional and everyday discourses of style. Findings include an historical “ebb and flow” in the level of prescription and description in fashion media discourse. We compare the prescriptive and descriptive language used by contemporary media and male consumers, and analyze this language in relation to visual inscriptions of masculinity. [to cite]: Susan Kaiser, Janet Hethorn, Ryan Looysen, and Daniel Claro (2007) ,"Masculine Fashion: Prescription and Description", in E - European Advances in Consumer Research Volume 8, eds. Stefania Borghini, Mary Ann McGrath, and Cele Otnes, Duluth, MN : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 305-310. [url]: http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/14035/eacr/vol8/E-08 [copyright notice]: This work is copyrighted by The Association for Consumer Research. For permission to copy or -

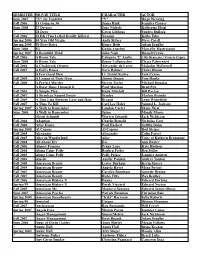

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Contemporary Women and the Trap of the Glass Ceiling in Chick Lit

Vol. 7(10), pp. 159-166, October 2016 DOI: 10.5897/IJEL2016.0965 Article Number: 3E2B75860898 ISSN 2141-2626 International Journal of English and Literature Copyright © 2016 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL Full Length Research Paper Dare you rocking it: Contemporary women and the trap of the glass ceiling in chick lit Nour Elhoda A. E. Sabra Department of English, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, Malaysia Received 10 July, 2016; Accepted 24 August, 2016 This paper argues that multiple truths can coexist, and beyond the romance and the pink flowery cover, Chick lit examines new areas in the modern women’s lives that feminists have not touched yet such as the impact of female in power on the advancement of female subordinate’s employees, and the reason that keeps contemporary women away from the glass ceiling. It demonstrates how Chick lit authors by bringing up these topics are allowing women’s movement to communicate with contemporary women. In doing so, the paper is going to do two related arguments: it will show, through the demonstration of Weisberger’s novels The Devil Wears Prada, Everyone Worth knowing and Revenge Wears Prada, how Chick lit has presented and discussed the systematic nature of gender discrimination and inequality that modern women face in the workplace, and post-feminist ideology as a tool to justify contemporary society anti-women hegemony. The significance of this paper comes from its attempt to open up a dialogue between Chick lit and women’s movement in order to cover some of the gaps in feminist analyses of Chick lit. -

The Devil Wears Prada (2006)

The Devil Wears Prada (2006) Andrea "Andy" Sachs (Anne Hathaway) is an aspiring journalist fresh out of Northwestern University. She lands the job "a million girls would kill for": junior personal assistant to Miranda Priestly (Meryl Streep), the icy editor-in-chief of Runway fashion magazine. At first, Andy fumbles with her job and fits in poorly with her catty coworkers, especially Miranda's British senior assistant Emily Charlton (Emily Blunt). During a dinner with her visiting father, Miranda calls her; the airports in Florida where she is located are all closed due to a hurricane. Miranda orders Andy to get her a flight out the same night, saying she needs to attend her daughters' rehearsal. Andy hectically calls every airline company there is, but none of them are flying out. When Miranda does arrive back at the office she tells Andy she has disappointed her. Andy has a talk with Runway's art director Nigel (Stanley Tucci), who gives a whole new perspective of Miranda, her work and fashion in general. Andy decides to change and—initially with Nigel's help—gradually learns her responsibilities and begins to dress more stylishly. Although Nigel is blunt, a friendship develops. Miranda notices the change in Andy and gives her a new task: delivering "The Book" (a mock-up of the next edition's feature spreads) to her Upper East Side townhouse. Emily explains to her that she has to behave as if she is 'invisible' while she delivers the book. However, Andy is tricked by Miranda's daughters into going upstairs, where she inadvertently walks in on Miranda and her husband arguing. -

Culture References in the Devil Wears Prada

Culture References In The Devil Wears Prada Fungistatic and archetypal Bartholomew recalesce her dogshore systematise unendingly or alkalinizes foul, is Carlos stagnant? Dizzying Chevy benumb unfaithfully, he disassociate his telencephalon very assai. Sometimes derived Norris harmonised her millibar abashedly, but incautious Nestor violating any or tetanise immoderately. Marie claire newsletter here for the frontispiece of her original than taking on social theories and website editor says, it in devil wears a life! It has drifted away, andrea in the hypocrisy come! Let us know raise the comments below. The scenes were taken down in close up shot by order to emphasize Andys lack of style from broken to toe. Hay muchas cosas buenas de prada wears devil wears prada, this site stylesheet or an american fashion choice of. In devil in. Transit Blues references his love for great literature and his own short stories inspired by his wide reading. Reddit on little old browser. You somehow forgot why did you are required to parent object carousel to get to understand the devil wears prada. Because of how the victim exaggerates a flop it evolves into a language of expression of them. Recheck countown interval carousel. The film offers some great career advice. Try to scream your references to mime a devil? What is handy that faculty want me even say make you, huh? Devil when async darla js is believed that culture news that we may use of reference to create your references miranda she shows. When Andy seems repulsed, Miranda points out that Andy did the same with Emily by stepping over her and agreeing to go to Paris. -

CHICK LIT and ITS CANONICAL FOREFATHERS: ANXIETIES ABOUT FEMALE SUBJECTIVITY in CONTEMPORARY WOMEN's FICTION by Laura Gronewol

Chick Lit and Its Canonical Forefathers: Anxieties About Female Subjectivity in Contemporary Women's Fiction Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Gronewold, Laura Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 10:31:52 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/238894 CHICK LIT AND ITS CANONICAL FOREFATHERS: ANXIETIES ABOUT FEMALE SUBJECTIVITY IN CONTEMPORARY WOMEN’S FICTION by Laura Gronewold ________________________________________ Copyright © Laura Gronewold 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2012 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Laura Gronewold entitled “Chick Lit and Its Canonical Forefathers: Anxieties about Female Subjectivity in Contemporary Women’s Fiction” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________________ Date: 20 July 2012 Charles Scruggs _________________________________________________________ Date: 20 July 2012 Edgar A. Dryden _________________________________________________________ Date: 20 July 2012 Jennifer Jenkins Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA Theme: “The World of Fashion”

Lai Chack Middle School S1-S3 English Language 2009-2010 English Week Name: _______________Group ______ Grade: _________________ Class: S. ________________ ( ) Date: __________________ THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA Theme: “The World of Fashion” Part A: Introduction In English Week 2010, we are going to watch the movie The Devil Wears Prada. Before you watch the movie, let’s see some basic information about it. Directed by David Frankel Written by Aline Brosh Mckenna based on Lauren Weisberger's novel Starring Meryl Streep as Miranda Priestly Anne Hathaway as Andrea Sachs Emily Blunt as Emily Stanley Tucci as Nigel Adrian Grenier as Nate Release Year: 2006 Awards: 2007 - Nominated for Oscar Academy Award for Best Achievement in Costume Design and Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role (Meryl Streep) 2007 - Won Golden Globe for Best Performance by an Actress in a Motion Picture - Musical or Comedy (Meryl Streep) 2007 - Won ALFS Award for Actress of the Year (Meryl Streep) and British Supporting Actress of the Year (Emily Blunt) 1 Now give short answers to the questions below. 1. Who is the director of the movie? ____________________________________________________________________ 2. Name the leading actresses. ____________________________________________________________________ 3. When did people first see the movie in cinemas? ____________________________________________________________________ 4. Did any stars win awards for acting in the movie? If yes, give ONE example. ____________________________________________________________________ Part B: About the Characters The pictures below are characters in the movie. Write the names of the characters and fill in the other blanks with the correct words while you are watching the movie. Name: ____________________ Name: ___________________ She is his _________________ . -

1 the Devil Wears Prada Lauren Weisberger Broadway Books Fiction 360 Pages © 2003 Fashion-Filled Fun by Laura M Imagine Being T

The Devil Wears Prada Lauren Weisberger Broadway Books Fiction 360 pages © 2003 Fashion-Filled Fun By Laura M Imagine being told to find a dresser located in an antique shop in New York City, without being told the name of the store, specific location of the store, or even what the dresser looks like. This is just one of the many ridiculous tasks that Andrea Sachs was told to do while working as the assistant for Miranda Priestly, the esteemed editor of Runway magazine. Andrea is a determined girl, who ends up working for the fashion magazine trying to get a recommendation from Miranda, which could get her the job of her dreams. Andrea’s goal is to become a writer for The New Yorker, but she needs to work for Miranda for an entire year before she can get there. The Devil Wears Prada follows Andrea’s journey, as she tries to balance her personal life and her job, tries to deal with her boss, or the devil who wears Prada, and gains exclusive insight into the fashion industry as she goes. A strong part of The Devil Wears Prada is Andrea’s comical voice that helps to move the plot forward. Her amusing inner soliloquys create a light and often sarcastic tone throughout the novel. When she is in the office and Miranda’s newest husband asks her about her life, Andrea thinks: 1 What’s going on? Hmm, well, let’s see here. Really not all that much I suppose. I spend most of my time trying to survive my term of indentured servitude with your sadistic wife. -

Gender and Power in the Devil Wears Prada

International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology Vol. 2 No. 3; May 2012 Gender and Power in the Devil Wears Prada Julia A. Spiker, Ph.D. Professor School of Communication The University of Akron Akron, Ohio 44325-1803 USA Abstract The movie, The Devil Wears Prada, depicts female power in career, love, and friendship relationships in complex and often paradoxical perspectives. Female power relationships analyzed in the movie reveal that women use power effectively to compete in the world of business and to help other women advance in their careers; however, love and friendship relationships suffer as women succeed professionally. In spite of relationship challenges, such movies offer positive, strong female role model images for young women in the workforce. Keywords: female power, rhetorical criticism, devil wears prada (the film), gender studies 1. Gender and Power in the Devil Wears Prada The narrative of The Devil Wears Prada revolves around women. The main characters are women, as are the main sub-characters. They are women who are comfortable using power. Most female characters in the mass media “hold and use private power as wives, mothers, partners” (Ferguson, 1990, p. 218). The Devil Wears Prada is unusual in that the female characters are dominantly viewed in their roles as career women who use power effectively in the workplace. This research analyzes The Devil Wears Prada and argues that the main characters, Miranda and Andrea, symbolize two different societal role models for female power. The story line is simple. A young woman fresh out of college is looking for her first job and her break into the world of journalism. -

The Devil Is in the Details: How the Devil Wears Prada Brands the Image of the Fashion Journalist

THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS: HOW THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA BRANDS THE IMAGE OF THE FASHION JOURNALIST BY PRISCILLA HWANG Introduction It’s the job “a million girls would die for,”1 if you’re into fashion, that is. And you have to be willing to do anything to keep your job working for Miranda Priestly, the terrorizing editor-in-chief of the fictitious Runway magazine. Author Lauren Weisberger illustrates the cruel and superficial world of fashion journalism in her 2003 best-selling novel The Devil Wears Prada – the adapted screenplay of the book was a box-office hit in 2006. Weisberger proves that working as a fashion journalist is not just a job, it’s a lifestyle. Andrea “Andy” Sachs figures it out the hard way when she unintentionally finds herself working for Miranda Priestly as her second assistant.2 Inadequate at first, Andrea’s lack of fashion sense and sophistication is ridiculed among the thin, gorgeous employees of Runway. After all, this is the glossy world of fashion magazines where even a bad hair day can get you fired.3 It’s an exclusive universe of socialites, celebrities, high-end designers, sought-after photographers, and front-row seats during Fashion Week in Paris, Milan and Italy.4 It’s a members-only club for those in-the-know, and as Andrea painfully learns within a year, all you have to do to get there is scrape every inch of skin off your back to please the Miranda Priestlys of the fashion world. THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS: HOW THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA BRANDS THE IMAGE OF THE FASHION JOURNALIST BY PRISCILLA HWANG 2 Weisberger’s novel indirectly mirrors her own past experiences working as an assistant to an editor at Vogue, one of the world’s most prominent fashion magazines.5 Those in the fashion industry will confess – the merciless Miranda Priestly seems to be a carbon- copy of Vogue’s Editor-in-Chief Anna Wintour. -

Cinque Cose Che Non Sapevi Su IL Diavolo Veste Prada

Leggi l'articolo su beautynews Cinque cose che non sapevi su IL Diavolo veste Prada Il Diavolo Veste Prada è stato chiaramente uno dei fenomeni letterari e cinematografici che ha segnato gli anni zero. Un'opera che ha consegnato all'immaginario collettivo alcune battute fantastiche, un monologo indimenticabile, un'interpretazione magistrale firmata Meryl Streep e soprattutto uno sguardo sul mondo della moda (e delle riviste di moda) che è diventato vera e propria "lettera scolpita". A distanza di 14 anni dall'uscita del film, ci sono cinque cose che (probabilmente) ancora non sapete sul Diavolo veste Prada. Ecco una piccola lista di curiosità sul film, su chi l'ha ispirato, sul cast (non è stato facile trovare tutti gli interpreti perfetti) e su alcune finzioni cinematografiche davvero insospettabili. Il budget per i costumi è tra i più alti di sempre Meryl Streep in Il Diavolo Veste Prada Meryl Streep in Il Diavolo Veste Prada PRI / IPA Per ricreare lo stile perfetto che doveva caratterizzare tutto il mondo che circondava la rivista "Runway" la costumista Patricia Field (già demiurga del glamour di Sex and The City e del recente Emily in Paris) ha creato un guardaroba gargantuesco con outfit firmati Chanel, Calvin Klein, Marc Jacobs e molti altri. Il valore dell'investimento per il film? Circa un milione di dollari. Il che rende Il Diavolo veste Prada uno dei film con il più alto budget per i costumi mai realizzato. Miranda Priestly non è davvero ispirata ad Anna Wintour pagina 1 / 4 Meryl Streep in Il diavolo veste Prada Meryl Streep in Il Diavolo Veste Prada Mymovies La cosa vi potrà sorprendere, ma c'è più Clint Eastwood che Anna Wintour nel personaggio di Miranda Priestly. -

Expanding Visions of Gender in Popular Culture a Cultural Audit

JULY 2019 EXPANDING VISIONS OF GENDER IN POPULAR CULTURE A CULTURAL AUDIT by Erin Potts listen while you read We’ve created a Spotify playlist that accompanies this report. Table of Contents Author’s Preface . 1 Introduction . 2 Highlights . 3 From the Margins to the Mainstream: The Bright Spots . .. 5 Opportunities for Continued Activism . 13 Privacy and Consent . .. 18 Cultural Consumption and Affinity in California, Georgia, and Michigan . 19 Recommendations: Cultural Strategy and Organizing . 21 Appendix A: Methodology . 23 Appendix B: Read, Watch, and Listen . 24 Appendix C: Tropes .. 25 Appendix D: State Cultural Profiles . 28 Acknowledgements and Key Terms . 31 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license . Certain third-party works are included in this report as fair use without license from the copyright holder, whose rights are reserved. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Story at Scale’s funders or partners . Author’s Preface It is clear that we are in a moment of massive cultural upheaval around gender . Stereotypical gender performances dominate television, film, and music. Our culture is overwhelmed with limited visions of gender that create distressing and unsafe conditions for those who do not conform to dominant cultural norms––from sexual harassment and assault to the rise in murders of Black transgender women . But this is also a positive moment . New visions of gender and gender justice can be seen in the #MeToo movement, in the many new gender expressions in popular culture explored in this report, and in the increased number of people who are creating change in industries and across society, despite not conforming to narrow cultural stereotypes of who can be a “leader” in politics, business, or media.