Gender and Power in the Devil Wears Prada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Nine to Five to the Devil Wears Prada

Women’s Studies, 40:336–350, 2011 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0049-7878 print / 1547-7045 online DOI: 10.1080/00497878.2011.553574 BACKLASH: FROM NINE TO FIVE TO THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA LILIAN CALLES BARGER University of Texas, Dallas Susan Faludi’s 1991 bestselling book Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women described the position of women in the United States that year. Faludi pointed out the media pundits who declared that while women had made unprecedented advances in the prior two decades and “equality . had largely been won,” women were suffering from “new problems that have no name” (Faludi x). Experts announced a plague of barren wombs, bad nerves, fear of intimacy, alcoholism, and chronic loneliness falling on women. The liberal feminism that emerged in the 1960s had created a woman who was successful at work but a wreck at home. Liberated from male control and pursuing their own ambitions, society had concluded, “Women were unhappy because they were free” (x). Faludi observed that the decade of the 1980s produced a steady stream of articles, books, and television shows all with the same message, “the awful truth about women’s lib” (xi). According to these sources, women needed men and stable domestic rela- tionships. By 1990, women had become familiar with the news that career success had reduced their chances of marriage and children, ensuring them a lifetime of unhappiness. Faludi called the unrelenting news about the dangers of success the “backlash” against women’s equality (xix). Film trends starting in the 1970s and continuing into the new millennium demonstrated the endur- ing validity of Faludi’s argument. -

The Czech Republic: on Its Way from Emigration to Immigration Country

No. 11, May 2009 The Czech Republic: on its way from emigration to immigration country Dušan Drbohlav Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Lenka Lachmanová-Medová Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Zden ěk Čermák Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Eva Janská Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Dita Čermáková Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Dagmara Dzúrová Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Table of contents List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. 3 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 1. Social and Migration Development until 1989 ...................................................................... 7 1.1. Period until the Second World War ................................................................................ 7 1.2. Period from 1945 to 1989 .............................................................................................. 10 2. Social and Migration Development in the Period -

Strategies in an Arts Program for Adults with Atypical Communication

STRATEGIES IN AN ARTS PROGRAM FOR ADULTS WITH ATYPICAL COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES AND ADAPTATIONS IN AN ARTS PROGRAM FOR ADULTS WITH ATYPICAL COMMUNICATION A Master’s Degree Thesis by Christina Lukac to Moore College of Art & Design In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Art Education with an Emphasis in Special Populations Philadelphia, PA August 2017 Accepted: ________________________________ Lauren Stichter | Graduate Program Director Masters in Art Education with an Emphasis in Special Populations STRATEGIES IN AN ARTS PROGRAM FOR ADULTS WITH ATYPICAL ii COMMUNICATION Abstract The purpose of this study was to observe and implement strategies and adaptations in an arts program for adults with atypical communication due to developmental and intellectual disabilities. This study was conducted in the field using an action research approach with triangulated methods of data collection including semi- structured interviews, participant observations, and artwork analysis. While research was conducted in two different art programs with similar populations, the main site of study was at SpArc Service’s Cultural Arts Center located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The secondary site was at Center for Creative Works located in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania. The data collected between these sites produced common trends in strategies and adaptations that are used in the art room. Individual case studies conducted at SpArc Services allowed strategies to be implemented and documented in the art room. When implementing these findings, I saw how these strategies supported the participant’s goals as outlined in their Individual Outcome Summary. While working with the individual participants, areas of art making included textiles, mixed-media materials, and pop culture references. -

Association for Consumer Research

ASSOCIATION FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH Labovitz School of Business & Economics, University of Minnesota Duluth, 11 E. Superior Street, Suite 210, Duluth, MN 55802 Masculine Fashion: Prescription and Description Susan Kaiser, University of California, Davis, USA Janet Hethorn, University of Delaware, USA Ryan Looysen, University of California, Davis, USA Daniel Claro, University of Delaware, USA The presentation will focus on the interplay among prescription, description, and inscription in social constructions of masculine fashion. Based upon (a) archival, critical discourse analyses of men’s magazines (e.g., Esquire, GQ, Details) and (b) interviews and surveys with U.S. male consumers, we explore the complex relationship between institutional and everyday discourses of style. Findings include an historical “ebb and flow” in the level of prescription and description in fashion media discourse. We compare the prescriptive and descriptive language used by contemporary media and male consumers, and analyze this language in relation to visual inscriptions of masculinity. [to cite]: Susan Kaiser, Janet Hethorn, Ryan Looysen, and Daniel Claro (2007) ,"Masculine Fashion: Prescription and Description", in E - European Advances in Consumer Research Volume 8, eds. Stefania Borghini, Mary Ann McGrath, and Cele Otnes, Duluth, MN : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 305-310. [url]: http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/14035/eacr/vol8/E-08 [copyright notice]: This work is copyrighted by The Association for Consumer Research. For permission to copy or -

2 the Idea.Pages

THE IDEA ‘Sure I’ve got a minute. What’s your series about?’ Imagine this: through luck or perseverance, you have tracked down the exact producer you want to meet. You’ve done your homework. You know exactly who this person is, what shows they made and why they are perfect to executive produce your series. You’ve got them on the phone or you’ve planted yourself directly in their path outside a screening. However it happens, you’ve got their attention. For about a minute. How you use that minute will determine whether you are invited to come in for a meeting, or whether that producer will excuse themselves with a polite, ‘good luck.’ So what do we say? How do we best answer this basic question: ‘What is your series about?’ I’m going to give you a formula for this in a minute, but before I do, it’s important that you understand that there are at least two levels of communication going on in this situation. There is the WHAT (i.e., basic information that describes your series) and there is the HOW (i.e., the level of confidence and professionalism with which you speak). Which of these two do you think matters most at the outset? You don’t need to be a deep student of psychology or interpersonal relations to know that confidence is crucial in a situation like this. How you communicate matters tremendously. And yet, where is this confidence supposed to come from? You, someone who has never made a tv series? Perhaps never even staffed or written a pilot – how are you supposed to convey the confidence and authority to make this person comfortable enough to trust you? It’s actually pretty simple: practice. -

Teen-Targeted Broadcast TV Can Be Vulgar… but Stranger Things Are

Teen-Targeted Broadcast TV Can Be Vulgar… But Stranger Things Are Happening On Netflix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The entertainment industry has, for decades, The Parents Television Council renews its call for cautioned parents who want to protect their children wholesale reform to the entertainment industry- from explicit content to rely on the various age- controlled ratings systems and their oversight. based content ratings systems. The movie industry, There should be one uniform age-based content the television industry, the videogame industry rating system for all entertainment media; the and the music industry have, individually, crafted system must be accurate, consistent, transparent medium-specific rating systems as a resource to and accountable to those for whom it is intended to help parents. serve: parents; and oversight of that system should be vested primarily in experts outside of those who In recent years, the Parents Television Council has produce and/or distribute the programming – and produced research documenting a marked increase who might directly or indirectly profit from exposing in profanity airing on primetime broadcast television. children to explicit, adult-themed content. All of the television programming analyzed by the PTC for those research reports was rated as appropriate for children aged 14, or even younger. Today, with much of the nation ostensibly on lockdown as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, children are at home instead of at school; and as a result, they have far greater access to entertainment media. While all forms of media consumption are up, the volume of entertainment programming being consumed through over-the-top streaming platforms has spiked dramatically. -

(IOM) (2019) World Migration Report 2020

WORLD MIGRATION REPORT 2020 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This flagship World Migration Report has been produced in line with IOM’s Environment Policy and is available online only. Printed hard copies have not been made in order to reduce paper, printing and transportation impacts. The report is available for free download at www.iom.int/wmr. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 717 9111 Fax: +41 22 798 6150 Email: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int ISSN 1561-5502 e-ISBN 978-92-9068-789-4 Cover photos Top: Children from Taro island carry lighter items from IOM’s delivery of food aid funded by USAID, with transport support from the United Nations. © IOM 2013/Joe LOWRY Middle: Rice fields in Southern Bangladesh. -

AN EXAMINATION of EMILY DICKINSON THESIS Presented To

310071 EMILY AND THE CHILD: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CHILD IMAGE IN THE WORK OF EMILY DICKINSON THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Nancy Eubanks McClaran, B. A. Denton, Texas May, 1974 ABSTRACT mcClaran, Nancy Eubanks, Emily and the Child.: An Examination of the Child Image in the Work of Emily Dickinson. Master of Arts (English), May, 1974, 155 pp., 6 chapters, bibliography 115 titles. The primary sources for this study are Dickinson's poems and letters. The purpose is to examine child imagery in Dickinson's work, and the investigation is based on the chronological age of children in the images. Dickinson's small child exists in mystical communion with nature and deity. Inevitably the child is wrenched from this divine state by one of three estranging forces: adult society, death, or love. After the estrangement the state of childhood may be regained only after death, at which time the soul enters immortality as a small child. The study moreover contends that one aspect of Dickinson's seclusion was an endeavor to remain a child. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 II. INFANCY - .-- -. * . 21 III. EARLY CHILDHOOD: EARTH'S CONFIDING TIME * " 0 27 IV. THE PROCESSOF ESTRANGEMET . ... 64 V. THE ESTRANGED CHILD ...--...... " 0 0 123 VI. CHILDHOOD IN MORTALITY . 134 BIBLIOGRAPHY 0 0-- 0 -- 40.. .. .. " 0 0 156 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The poetry of Emily Dickinson has great significance in a study of imagery. Although that significance seemed apparent to critics almost from the moment the first volume of her poems was posthumously published in 1890, very little has been written on Dickinson's imagery. -

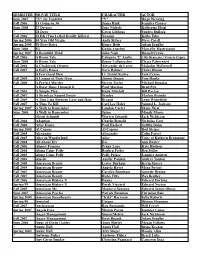

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Contemporary Women and the Trap of the Glass Ceiling in Chick Lit

Vol. 7(10), pp. 159-166, October 2016 DOI: 10.5897/IJEL2016.0965 Article Number: 3E2B75860898 ISSN 2141-2626 International Journal of English and Literature Copyright © 2016 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL Full Length Research Paper Dare you rocking it: Contemporary women and the trap of the glass ceiling in chick lit Nour Elhoda A. E. Sabra Department of English, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, Malaysia Received 10 July, 2016; Accepted 24 August, 2016 This paper argues that multiple truths can coexist, and beyond the romance and the pink flowery cover, Chick lit examines new areas in the modern women’s lives that feminists have not touched yet such as the impact of female in power on the advancement of female subordinate’s employees, and the reason that keeps contemporary women away from the glass ceiling. It demonstrates how Chick lit authors by bringing up these topics are allowing women’s movement to communicate with contemporary women. In doing so, the paper is going to do two related arguments: it will show, through the demonstration of Weisberger’s novels The Devil Wears Prada, Everyone Worth knowing and Revenge Wears Prada, how Chick lit has presented and discussed the systematic nature of gender discrimination and inequality that modern women face in the workplace, and post-feminist ideology as a tool to justify contemporary society anti-women hegemony. The significance of this paper comes from its attempt to open up a dialogue between Chick lit and women’s movement in order to cover some of the gaps in feminist analyses of Chick lit. -

The Devil Wears Prada (2006)

The Devil Wears Prada (2006) Andrea "Andy" Sachs (Anne Hathaway) is an aspiring journalist fresh out of Northwestern University. She lands the job "a million girls would kill for": junior personal assistant to Miranda Priestly (Meryl Streep), the icy editor-in-chief of Runway fashion magazine. At first, Andy fumbles with her job and fits in poorly with her catty coworkers, especially Miranda's British senior assistant Emily Charlton (Emily Blunt). During a dinner with her visiting father, Miranda calls her; the airports in Florida where she is located are all closed due to a hurricane. Miranda orders Andy to get her a flight out the same night, saying she needs to attend her daughters' rehearsal. Andy hectically calls every airline company there is, but none of them are flying out. When Miranda does arrive back at the office she tells Andy she has disappointed her. Andy has a talk with Runway's art director Nigel (Stanley Tucci), who gives a whole new perspective of Miranda, her work and fashion in general. Andy decides to change and—initially with Nigel's help—gradually learns her responsibilities and begins to dress more stylishly. Although Nigel is blunt, a friendship develops. Miranda notices the change in Andy and gives her a new task: delivering "The Book" (a mock-up of the next edition's feature spreads) to her Upper East Side townhouse. Emily explains to her that she has to behave as if she is 'invisible' while she delivers the book. However, Andy is tricked by Miranda's daughters into going upstairs, where she inadvertently walks in on Miranda and her husband arguing. -

The Importance of Diversity on Film By: Ashlyn Hauser

The Importance of Diversity on Film By: Ashlyn Hauser Across the world, television has been changing. How exactly? There have been massive steps in the representation of people of color, women, the LGBTQ+ community, and even shows and films including developmental and mental disorders. With shows like Atypical, On My Block, and Tales of the City, diversity and intersectionality are on the rise. You may be wondering, why is this so important? Showing an across-the-board diverse cast, especially in teen shows, could help teens identify with themselves more, showing a character in the LGBTQ+ community could be eye-opening for those who don’t understand, and it could change the assumptions or stereotypes of some. Atypical is a coming-of-age television series on Netflix. Created by Robia Rashid, the series focuses on 18-year-old Sam Gardener (Keir Gilchrist) who’s been diagnosed with autism when he was a little boy. In his school, Sam is sometimes seen as a nerd by his peers, and is called a “freak.” When joining college, Sam was told that only 1 in 5 with autism graduate, and end in success. This haunts him, and he begins frantically preparing for everything. Many people believe that people on the autism spectrum aren’t capable of succeeding in life, and that’s where many are wrong. Sam shows that just because he was diagnosed with something that makes him a little different than others, he can be accepted and as successful as anyone else. In Atypical’s most recent season, Casey Gardener (Brigette Lundy-Paine), Sam’s younger sister, is struggling with something she’s never felt before.