Journal of Asia Adventist Seminary for 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Seventh-Day Adventist Colleges and Universities

DIRECTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ADVENTIST ACCREDITING ASSOCIATION Accrediting Association of Seventh-day Adventist Schools, Colleges, and Universities 12501 Old Columbia Pike, Silver Spring, Maryland 20904 USA 2018-2019 CONTENTS Preface 5 Board of Directors 6 Adventist Colleges and Universities Listed by Country 7 Adventist Education World Statistics 9 Adriatic Union College 10 AdventHealth University 11 Adventist College of Nursing and Health Sciences 13 Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies 14 Adventist University Cosendai 16 Adventist University Institute of Venezuela 17 Adventist University of Africa 18 Adventist University of Central Africa 20 Adventist University of Congo 22 Adventist University of France 23 Adventist University of Goma 25 Adventist University of Haiti 27 Adventist University of Lukanga 29 Adventist University of the Philippines 31 Adventist University of West Africa 34 Adventist University Zurcher 36 Adventus University Cernica 38 Amazonia Adventist College 40 Andrews University 41 Angola Adventist Universitya 45 Antillean Adventist University 46 Asia-Pacific International University 48 Avondale University College 50 Babcock University 52 Bahia Adventist College 55 Bangladesh Adventist Seminary and College 56 Belgrade Theological Seminary 58 Bogenhofen Seminary 59 Bolivia Adventist University 61 Brazil Adventist University (Campus 1, 2 and 3) 63 Bugema University 66 Burman University 68 Central American Adventist University 70 Central Philippine Adventist College 73 Chile -

Servant Leadership, Sacrificial Service

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE FOR COLLEGE & UNIVERSITY PRESIDENTS Servant Leadership, Sacrificial Service March 24-27, 2014 Washington DC General Conference Department of Education AEO-PresidentsConferenceProgram.indd 1 3/19/14 2:24 PM Monday March 24, 2014 Time Presentation/Activity Presenter/Responsible Venue 16:30-18:00 Arrival, Registration Education Department GC Lobby 18:00-19:00 Welcome Reception Education Department GC Atrium 19:00-20:00 Showcase Divisions Auditorium Those requiring translation to Spanish, Portuguese or Russian may check out a radio at registration. Tuesday March 25, 2014 Time Presentation/Activity Presenter/Responsible Venue Dick Barron 08:00 – 09:00 Week of Prayer Auditorium Prayer: Stephen Currow 09:00 – 09:30 Welcome and Introductions Lisa Beardsley-Hardy Auditorium George R. Knight 09:30 – 10:30 Philosophy of Adventist Education Auditorium Coordinator: Lisa Beardsley-Hardy 10:30 – 10:45 Break Auditorium Ted Wilson 10:45 – 11:45 Role of Education in Church Mission Auditorium Coordinator: Ella Simmons 11:45 – 13:00 Lunch All GC Cafeteria Humberto Rasi 13:00 – 14:00 Trends in Adventist Education Auditorium Coordinator: John Fowler Gordon Bietz 14:00 – 15:15 Biblical Foundations of Servant Leadership Auditorium Coordinator: John Wesley Taylor V Panel: Susana Schulz, Norman Knight *14:00 – 15:15 Role of President’s Spouse 2 I-18 Demetra Andreasen, & Yetunde Makinde 15:15 – 15:30 Break Auditorium Panel, Discussion: Niels-Erik Andreasen, 15:30 – 16:30 Experiences and Expectations Juan Choque, Sang Lae Kim, Stephen Guptill, -

Chronology of Seventh-Day Adventist Education: 1872-1972

CII818L8tl or SIYIITI·Ill IIYIITIST IIUCITIGI CENTURY OF ADVENTIST EDUCATION 1872 - 1972 ·,; Compiled by Walton J. Brown, Ph.D. Department of Education, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists ·t. 6840 Eastern Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20012 i/ .I Foreword In anticipation of the education centennial in 1972 and the publication of a Seventh-day Adventist chronology of education, the General Conference Department of Education started to make inquiries of the world field for historical facts and statistics regarding the various facets of the church program in education. The information started to come in about a year ago. Whlle some of the responses were quite detalled, there were others that were rather general and indefinite. There were gaps and omissions and in several instances conflicting statements on certain events. In view of the limited time and the apparent cessation of incoming materials from the field, a small committee was named with Doctor Walton J. Brown as chairman. It was this committee's responsibility to execute the project in spite of the lack of substantiation of certain information. We believe that this is the first project of its kind in the denomination's history. It is hoped that when the various educators and administrators re view the data about their own organizations, they will notify the Department of Education concerning any corrections and additions. They should please include supporting evidence from as many sources as possible. It is hoped that within the next five to ten years a revised edition may replace this first one. It would contain not only necessary changes, but also would be brought up to date. -

Journal of a Asia Adventist a Seminary S

J Journal of A Asia Adventist A Seminary S 9.1 2006 1908-4862 b i ? k-irn JOURNAL OF ASIA ADVENTIST SEMINARY (ISSN 1908-4862) formerly Asia Adventist Seminary Studies (ISSN 0119-8432) Theological Seminary Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies Volume 9 ■ Number 1 ■ 2006 Editor: Gerald A. Klingbeil Associate Editor: Clinton Walden Book Review Editor: Aro/isi M. Sokupa Subscription Manager: Emmer Chacon Cover Design: lames H. Park Copy Editors: Chantal 1. Klingbeil, Woodrow W. Whidden II EDITORIAL BOARD Aecio Cairns, Chacon, Gerald A. Klingbeil, Joel Musvosvi, Mxolisi M. Sokupa, Clinton Walden INTERNATIONAL REVIEW BOARD David W. Baker (Ashland Theological Seminary, USA) ■ Erich Baumgartner (Andrews Uni- versity, USA) • Peter van Bemmelen (Andrews University, USA) • Fernando L. Canale (An- drews University, USA) • loAnn Davidson (Andrews University, usA) • Richard M. Davidson (Andrews University, USA) • Jon Dybdahl (Andrews University, USA) • Craig A. Evans (Acadia Divinity College, CANADA) ■ Daniel E. Fleming (New York University, USA) • J. H. Denis Fortin (Andrews University, USA) ■ Mary GLIM (Kenyatta University, KENYA) • Frank M. Hasel (Bogenhofen Seminary, AUSTRIA) ■ Michael G. tinsel (Southern Adventist Univer- sity, USA) • Daniel Heinz (Friedensau Theologische Hochschule, GERMANY) ■ Richard S. Hess (Denver Seminary, USA) • (Wismar Keel (Fribourg University, SwiTzERLAND) • Martin G. Klingbeil (Helderberg College, SOUTH AFRICA) ■ lens Brunt: Kofoed (Copenhagen Lu- theran School of Theology, DENMARK) • Wagner Kuhn (Institute of World Mission, USA) • Carlos Martin (Southern Adventist University, USA) • John K. McVay (Walla Walla College, ■ USA) ■ Cynthia L. Miller (University of Wisconsin, USA) Ekkehnrdt Midler (Biblical Research Institute, USA) • Roberto Percyra (Universidad Peruana Union, PERU) • Gerhard Pfau& (Bibli- cal Research Institute, USA) • Stanley E. -

Adventist Libraries

Adventist Libraries Adventist Libraries Africa - Adventist University of Africa: Judith Thomas Library (Kenya) - Babcock University: Laz Otti Memorial Library (Nigeria) - Helderberg College: Pieter Wessels Library (South Africa) - Rusangu University (Zambia) - Solusi University (Zimbabwe) Asia - Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies: Leslie Hardinge Library (Philippines) - Adventist University of the Philippines: John Lawrence Detwiler Memorial Library (Philippines) - Asia Pacific International University (Thailand) - Hongkong Adventist College (Hong Kong) - Middle East University: George Arthur Keough Library (Lebanon) - Penang Adventist College of Nursing (Malaysia) Australia 1 / 3 Adventist Libraries - Avondale College (Australia) - Brisbane Adventist College (Queensland) - Longburn Adventist College (New Zealand) - Pacific Adventist University (Papua New Guinea) Central and South America - Antillas Adventist University: Dennis Soto Library (Puerto Rico) - Dominican Adventist University (Dominican Republic) - Monte Morelos University (Mexico) - Navojoa University: Benitor Juarez Library (Mexico) - Northern Caribbean University: Hiram Walters Library (Jamaica) - Universidad Adventista del Plata: Biblioteca E.I Mohr (Argentina) - Universidad Adventista de Bolivia: Biblioteca Sighart Klauss (Bolivia) - Universidad de Montemorelos: El Centro de Información-Biblioteca (Mexico) - University of Southern Caribbean (Trinidad) Europe - Bogenhofen Seminary (Austria) - Campus Adventiste du Salève: Bibliothèque Alfred-Vaucher (France) -

Journal of Asia Adventist Seminary for 2009

A S 12.1 2009 sn 1908-4862 JOURNAL OF ASIA ADVENTIST SEMINARY (ISSN 1908-4862) Theological Seminary Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies Volume 12 ■ Number 1 • 2009 Editor: Gerald A. Klingbeil Associate Editor: Mathilde Frey Book Review Editor: Mxo/isi M. Sokupa Subscription Manager: Marcus Witzig Cover Design: James H. Park Copy Editors: Chantal J. Klingbeil, Elsie dela Cruz, and Daniel Bediako EDITORIAL BOARD A. Cairus, M. Frey, G. A. Klingbeil, I. H. Park, M. M. Sokupa, D. Tasker, W. Whidden, M. Witzig INTERNATIONAL REVIEW BOARD David W. Baker (Ashland Theological Seminary, USA) ■ Erich Baumgartner (Andrews Univer- sity, USA) • Peter van Bemmelen (Andrews University, USA) • Fernando L. Canale (Andrews ■ University, USA) JoAnn Davidson (Andrews University, USA) ■ Richard M. Davidson (An- ■ drews University, USA) Jon Dybdahl (Andrews University, usA) ■ Craig A. Evans (Acadia Divinity College, CANADA) • Daniel E. Fleming (New York University, USA) ■ I. H. Denis Fortin (Andrews 'University, USA) ■ Mary Getui (Kenyatta University, KENYA) ■ Frank M. Hasel (Bogenhofen Seminary, AUSTRIA) ■ Michael G. Hasel (Southern Adventist University, usA) • Richard S. Hess (Denver Seminary, USA) ■ Othmar Keel (Fribourg University, SWITZERLAND) ■ Martin G. Klingbeil (Helderberg College, SOUTH AFRICA) ■ George R. Knight (Andrews Univer- ■ sity, USA) lens Bruun Kofoed (Copenhagen Lutheran School of Theology, DENMARK) ■ Wag- ner Kuhn (Institute of World Mission, usA) ■ Carlos Martin (Southern Adventist University, USA) • John K. McVay (Walla Walla University, USA) • Cynthia L Miller (University of Wiscon- ■ sin, USA) Ekkehardt Muller (Biblical Research Institute, USA) ■ Roberto Pereyra (UNASP, BRAZIL) • Gerhard Pfandl (Biblical Research Institute, USA) ■ Stanley E. Porter (McMaster Divin- ity College, CANADA) ■ Martin Probstle (Seminar Schloss Bogenhofen, AUSTRIA) ■ Nestor C. -

Directory of Seventh-Day Adventist Colleges and Universities

DIRECTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ADVENTIST ACCREDITING ASSOCIATION Accrediting Association of Seventh-day Adventist Schools, Colleges, and Universities 12501 Old Columbia Pike, Silver Spring, Maryland 20904 USA 2018-2019 1 CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Board of Directors ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Adventist Colleges and Universities Listed by Country ............................................................................................. 7 Adventist Education World Statistics ......................................................................................................................... 9 Adriatic Union College ............................................................................................................................... 10 AdventHealth University ........................................................................................................................... 11 Adventist College of Nursing and Health Sciences .................................................................................... 13 Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies ............................................................................... 14 Adventist University Cosendai .................................................................................................................. -

Phd in Religion & Thd Programs Program

PhD in Religion & ThD Programs Program Review 2017-2018 CRITERION 1: MISSION, HISTORY, IMPACT, AND DEMAND Program Review # 1. How does the program contribute to the mission of Andrews University and the Seventh-day Adventist Church? Andrews University Mission Statement: “Andrews University, a distinctive Seventh-day Adventist Christian Institution, transforms its students by educating them to seek knowledge and affirm faith in order to change the world.” Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Mission Statement: “We serve the Seventh-day Adventist Church by preparing effective leaders to proclaim the everlasting gospel and make disciples of all people in anticipation of Christ’s soon return.” PhD in Religion & ThD Programs, Mission Statement: “The doctor of Philosophy in Religion prepares teacher-scholars for colleges, seminaries and universities primarily to meet the needs of the worldwide Seventh-day Adventist Church.” Evaluation: This program builds on expertise and training developed in approved master's programs. It provides individuals equipped with skills and methods appropriate to genuine scholarship to do original and responsible research, and it promotes the proficient application of sound and valid principles of biblical interpretation and historical research. It seeks to acquaint students with the Judeo-Christian heritage and the findings of various branches of biblical scholarship and communicates the religious and ethical values of that heritage as found in Scripture and as understood by conservative Christians, in general, and the Seventh-day Adventist Church, in particular. 1 Program Review # 2. How does the history of the program define the contributions of the program to Andrews University? History: The PhD in Religion and ThD programs began in the SDA Theological Seminary in 1974-1975 (ThD) and 1982-1983 (PhD) under the leadership of Dr. -

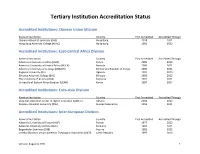

Tertiary Institution Accreditation Status

Tertiary Institution Accreditation Status Accredited Institutions: Chinese Union Mission Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Chinese Adventist Seminary (CAS) Hong Kong 2018 2021 Hong Kong Adventist College (HKAC) Hong Kong 1982 2022 Accredited Institutions: East-Central Africa Division Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Adventist University of Africa (AUA) Kenya 2005 2022 Adventist University of Central Africa (AUCA) Rwanda 2006 2021 Adventist University of Lukanga (UNILUK) Democratic Republic of Congo 2005 2021 Bugema University (BU) Uganda 1992 2023 Ethiopia Adventist College (EAC) Ethiopia 1993 2022 The University of Arusha (UOA) Tanzania 1992 2021 University of Eastern Africa Baraton (UEAB) Kenya 1987 2024 Accredited Institutions: Euro-Asia Division Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Ukrainian Adventist Center of Higher Education (UACHE) Ukraine 2004 2024 Zaoksky Adventist University (ZAU) Russian Federation 1994 2021 Accredited Institutions: Inter-European Division Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Adventist University of France (AUF) France 1977 2022 Adventus University Cernica (AUC) Romania 1997 2021 Bogenhofen Seminary (SSB) Austria 1983 2022 Czecho-Slovakian Union Adventist Theological Institute (CSUATI) Czech Republic 1997 2024 Version: August 4, 2021 1 Listing of Seventh-day Adventist Colleges and Universities, continued Friedensau Adventist University (FAU) Germany 1984 2021 Italian Adventist University Villa -

Post-Secondary Institutions

AAA Accreditation Status for Colleges and Universities The following list identifies by Division and Country all post-secondary institutions recognized and accredited by the Accrediting Association of Seventh-day Adventist Schools, Colleges, and Universities (AAA) along with the year each institution was first accredited and when current accreditation expires. Expiration is always on December 31 of the year identified, and during that same year an accreditation visit will be scheduled. The following definitions apply: ▪ Accredited: An institution with full accreditation. ▪ Mid-Level Training Institutions: Institutions that offer education which goes beyond secondary level education but is less than a bachelor’s degree. These include diploma teacher training, technical training in building and construction or other professional trades, and non-collegiate hospital-based schools of nursing (c.f. FE 30 15). ▪ In Candidacy: An institution in the process of application for full accreditation. Programs are still recommended for transfer to other accredited institutions. The maximum candidacy term is two years. ▪ In Pre-candidacy: An institution that has met basic criteria for operation and is working towards candidacy status. Programs are not yet recognized for transfer to other accredited institutions. The maximum pre-candidacy term is 5 years. ▪ On Probation: An institution that has held full accreditation but is not presently meeting accreditation expectations in certain critical areas. After a set period, accreditation will either be revoked -

Report to Spring Meeting of the GC Executive

Mission and Health Emphasis in Ministerial Training Curriculum November 19, 2014 Office of Archives, Statistics, and Research General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists David Trim, Ph.D R. William Cash, Ph.D. (Consultant) Galina Stele, D.Min. Table of Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ v Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Mission Courses ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Health Courses ............................................................................................................................................ 16 Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... 24 Appendix A – Additional Tables ................................................................................................................ 25 Appendix B – Comments ......................................................................................................................... -

Journal of Asia Adventist Seminary for 2007

i--. J Journal of A Asia Adventist A Seminary S 10.1 2007 .n 1908-4862 JOURNAL OF ASIA ADVENTIST SEMINARY (ISSN 1908-4862) formerly Asia Adventist Seminary Studies (ISSN 0119-8432) Theological Seminary Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies Volume 10 ■ Number 1 • 2007 Editor: Gerald A. Klingbeil Associate Editor: Clinton Wahlen Book Review Editor: Mxolisi M. Sokupa Subscription Manager: Emmer Chacon Cover Design: James H. Park Copy Editor: Chantal J. Klingbeil EDITORIAL BOARD A. Cain's, E. Chacon, G. A. Klingbeil, J. Musvosvi, J. H. Park, M. M. Sokupa, C. Wahletz INTERNATIONAL REVIEW BOARD David W. Baker (Ashland Theological Seminary, USA) • Erich Baumgartner (Andrews Univer- ■ sity, USA) Peter van Bemmelen (Andrews University, USA) • Fernando L. Canale (Andrews University, USA) ■ JoAnn Davidson (Andrews University, USA) • Richard M. Davidson (An- drews University, USA) ■ Jon Dybdahl (Andrews University, USA) ■ Craig A. Evans (Acadia ■ ■ Divinity College, CANADA) Daniel E. Fleming (New York University, USA) I. H. Denis Fortin (Andrews University, USA) ■ Mary Getui (Kenyatta University, KENYA) ■ Frank M. Hasel (Bogenhofen Seminary, AUSTRIA) ■ Michael G. Hasel (Southern Adventist University, ■ USA) Daniel Heinz (Friedensau Theologische Hochschule, GERMANY) • Richard S. Hess (Denver Seminary, USA) ■ Othmar Keel (Fribourg University, SWITZERLAND) ■ Martin G. Klingbeil (Helderberg College, Sarni AFRICA) ■ lens Bruun Kofoed (Copenhagen Lutheran School of Theology, DENMARK) ■ Wagner Kuhn (Institute of World Mission, USA) ■ Carlos Martin (Southern Adventist University, USA) ■ John K. McVay (Walla Walla University, USA) Cynthia L. Miller (University of Wisconsin, USA) • Ekkehardt Muller (Biblical Research Insti- tute, USA) ■ Roberto Pereyra (UNASP, BRAZIL) ■ Gerhard Pfandl (Biblical Research Institute, ■ USA) Stanley E. Porter (McMaster Divinity College, CANADA) ■ Martin Probstle (Seminar Schloss Bogenhofen, AUSTRIA) ■ Nestor C.