The Effect of Nuchal Cord on Perinatal Mortality and Long-Term Offspring Morbidity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outcomes of Labour of Nuchal Cord

wjpmr, 2020,6(8), 07-15 SJIF Impact Factor: 5.922 Research Article Ansam et al. WORLD JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL World Journal of Pharmaceutical and Medical Research AND MEDICAL RESEARCH ISSN 2455-3301 www.wjpmr.com WJPMR OUTCOMES OF LABOUR OF NUCHAL CORD Dr. Ansam Layth Abdulhameed*1 and Dr. Rozhan Yassin Khalil2 1Specialist Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Mosul, Iraq. 2Consultant Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Sulaymania, Iraq. *Corresponding Author: Dr. Ansam Layth Abdulhameed Specialist Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Mosul, Iraq. Article Received on 26/05/2020 Article Revised on 16/06/2020 Article Accepted on 06/07/2020 ABSTRACT Background: The nuchal cord is described as the umbilical cord around the fetal neck. It is classified as simple or multiple, loose or tight with the compression of the fetal neck. The term nuchal cord represents an umbilical cord that passes 360 degrees around the fetal neck. Objective: To find out perinatal outcomes in cases of labour of babies with nuchal cord and compared with other cases without nuchal cord. Patient and Methods: The prospective case-control study was conducted in maternity teaching hospital centre in Sulaimani / Kurdistan Region of Iraq, from June 2018 to April 2019. Cases of study divided into two groups. First group comprised of women in whom nuchal cord was present at the time of delivery they were labelled as cases. Second group was a control group composed of women in whom nuchal cord was absent at the time of delivery. Results: This study included (200) patients, (100) women with nuchal cord in labour. (59%) of the cases of nuchal cord in age group (20-29) years, (40%) of them were primigravida, delivery modes for women with nuchal cord were mainly normal vaginal delivery (76%) and cesarean section (24%). -

Blood Volume in Newborn Piglets: Effects of Time of Natural Cord Rupture, Intra-Uterine Growth Retardation, Asphyxia, and Prostaglandin-Induced Prematurity

Pediatr. Res. 15: 53-57 (1981) asphyxia natural cord rupture blood volume prostaglandin F 2 intra-uterine growth retardation Blood Volume in Newborn Piglets: Effects of Time of Natural Cord Rupture, Intra-Uterine Growth Retardation, Asphyxia, and Prostaglandin-Induced Prematurity 137 OTWIN LINDERKAMP, , KLAUS BETKE, MONIKA GUNTNER, GIOK H. JAP, KLAUS P. RIEGEL, AND KURT WALSER Department of Pediatrics and Department of Veterinary Gynecology, University of Munich, Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Summary (27, 29, 32). Placental transfusion is accelerated by keeping the infant below the placenta (19, 27), by uterine contractions (32), Blood volume (BV), red cell mass (RCM; Cr-51) and plasma 125 and by respiration of the newborn (19). Placental transfusion is volume ( 1-labeled albumin) were measured in lOS piglets from prevented by holding the infant above the placenta (19, 27), by 28 Utters shortly after birth. Spontaneous cord rupture in healthy maternal hypotension ( 17), by tight nuchal cord ( 13), and by acute piglets occurred during delivery (n • 25) or within 190 sec of birth intrapartum asphyxia (5, 12, 13). Intra-uterine asphyxia results in (n • 82). Spontaneous and induced delay of cord rupture resulted prenatal transfusion to the fetus (12, 13, 33). In a time-dependent Increase in BV and RCM. BV (x ± S.D.) at It is to be assumed that blood volume in newborn mammals is birth was 72.5 ± 10.5 ml/kg (RCM, 23.6 ± 4.6 ml/kg) In the 25 similarly influenced by placental transfusion as in the human piglets with prenatal cord rupture and 110.5 ± 12.9 ml/kg (RCM, neonate. -

Is Nuchal Cord a Cause of Concern?

ISSN: 2638-1575 Madridge Journal of Women’s Health and Emancipation Research Article Open Access Is Nuchal Cord a cause of concern? Surekha Tayade1*, Jaya Kore1, Atul Tayade2, Neha Gangane1, Ketki Thool1 and Jyoti Borkar1 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sewagram, India 2Department of Radiodiagnosis, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sewagram, India Article Info Abstract *Corresponding author: Context: The controversy about whether nuchal cord is a cause of concern and its Surekha Tayade adverse effect on perinatal outcome still persists. Authors express varying views and Professor Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology hence managing pregnancy with cord around the neck has its own concerns. Thus study Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical was carried out to find out the incidence of nuchal cord and its implications. Sciences Sewagram, 442102 Method: This was a prospective, cross sectional, comparative study carried out in the India Kasturba Hospital of MGIMS, Sewagram a rural medical tertiary care institute. All Tel: +917887519832 deliveries over a period of one year, were enrollled and studied for nuchal cord, tight or E-mail: [email protected] loose cord, number of turns, fetal heart rate irregulaties, pregnancy and perinatal Received: May 15, 2018 outcome. Accepted: June 19, 2018 Results: Total women with nuchal cord in labour room were 1116 (2.56%) of which Published: June 23, 2018 85.21 percent had single turn around the babies neck. Most of the babies ( 77.96 %) had Citation: Tayade S, Kore J, Tayade A, Gangane a loose nuchal cord, however 22.04 percent had a tight cord. -

A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of This Document Is Made Possible by Financial Contributions from Health Canada and Provincial and Territorial Governments

ICD-10-CA | CCI A Guide to Obstetrical Coding Production of this document is made possible by financial contributions from Health Canada and provincial and territorial governments. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada or any provincial or territorial government. Unless otherwise indicated, this product uses data provided by Canada’s provinces and territories. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be reproduced unaltered, in whole or in part and by any means, solely for non-commercial purposes, provided that the Canadian Institute for Health Information is properly and fully acknowledged as the copyright owner. Any reproduction or use of this publication or its contents for any commercial purpose requires the prior written authorization of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Reproduction or use that suggests endorsement by, or affiliation with, the Canadian Institute for Health Information is prohibited. For permission or information, please contact CIHI: Canadian Institute for Health Information 495 Richmond Road, Suite 600 Ottawa, Ontario K2A 4H6 Phone: 613-241-7860 Fax: 613-241-8120 www.cihi.ca [email protected] © 2018 Canadian Institute for Health Information Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre Guide de codification des données en obstétrique. Table of contents About CIHI ................................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. -

Effects of Delayed Versus Early Cord Clamping on Healthy Term Infants

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 893 Effects of Delayed versus Early Cord Clamping on Healthy Term Infants OLA ANDERSSON ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6206 ISBN 978-91-554-8647-1 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-198167 2013 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Rosénsalen, Ingång 95/96, Akademiska Barnsjukhuset, Uppsala, Thursday, May 23, 2013 at 09:30 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Andersson, O. 2013. Effects of Delayed versus Early Cord Clamping on Healthy Term Infants. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 893. 66 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-8647-1. The aim of this thesis was to study maternal and infant effects of delayed cord clamping (≥180 seconds, DCC) compared to early (≤10 seconds, ECC) in a randomised controlled trial. Practice and guidelines regarding when to clamp the cord vary globally, and different meta- analyses have shown contradictory conclusions on benefits and disadvantages of DCC and ECC. The study population consisted of 382 term infants born after normal pregnancies and ran- domised to DCC or ECC after birth. The primary objective was iron stores and iron defi- ciency at 4 months of age, but the thesis was designed to investigate a wide range of sug- gested effects associated with cord clamping. Paper I showed that DCC was associated with improved iron stores at 4 months (45% higher ferritin) and that the incidence of iron deficiency was reduced from 5.7% to 0.6%. -

Potentially Asphyxiating Conditions and Spastic Cerebral Palsy in Infants of Normal Birth Weight

Fetus-Placenta-N ewborn Potentially asphyxiating conditions and spastic cerebral palsy in infants of normal birth weight Karin B. Nelson, MD, and Judith K. Grether, PhD Bethesda, Maryland, and Emeryville, California OBJECTIVE: Our purpose was to examine the association of cerebral palsy with conditions that can inter rupt oxygen supply to the fetus as a primary pathogenetic event. STUDY DESIGN: A population-based case-control study was performed in four California counties, 1983 through 1985, comparing birth records of 46 children with disabling spastic cerebral palsy without recognized prenatal brain lesions and 378 randomly selected control children weighing 2:2500 g at birth and surviving to age 3 years. RESULTS: Eight of 46 children with otherwise unexplained spastic cerebral palsy, all eight with quadriplegic cerebral palsy, and 15 of 378 controls had births complicated by tight nuchal cord (odds ratio for quadriplegia 18, 95% confidence interval 6.2 to 48). Other potentially asphyxiating conditions were uncommon and none was associated with spastic diplegia or hemiplegia. Level of care, oxytocin for augmentation of labor, and surgical delivery did not alter the association of potentially asphyxiating conditions with spastic quadriplegia. Intrapartum indicators of fetal stress, including meconium in amniotic fluid and fetal monitoring abnormalities, were common and did not distinguish children with quadriplegia who had potentially asphyxiating conditions from controls with such conditions. CONCLUSION: Potentially asphyxiating conditions, chiefly tight nuchal cord, were associated with an appre ciable proportion of unexplained spastic quadriplegia but not with diplegia or hemi-plegia. Intrapartum abnor malities were common both in children with cerebral palsy and controls and did not distinguish between them. -

HAC 2016 ABSTRACT for Oral Presentations

HAC 2016 ABSTRACT for Oral Presentations Presentation no.: F1.6 Presenting Author: M T SOO Dr, KWH ACON(PAD) Project title Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping in Premature Neonates Author(s) SING C(1), LAM YY (2) , LAU WL(1), SOO M T(2), PAU B(2), TAI S M (1), LEUNG Y N(1),NG D (2), LEUNG W C (1) Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital (1) Department of Paediatrics, Kwong Wah Hospital (2) Keyword(s) delayed umbilical cord clamping premature neonates neonatal jaundice intraventricular hemorrhage necrotizing enterocolitis Approval by Ethics Committee: N ****************************************************************************** Introduction Early umbilical cord clamping (<20 seconds after birth) has been a routine for decades. Recent evidence reveals delayed cord clamping (30 seconds or more after birth) allows blood flow between the placenta and neonate. The return of placental blood volume to the neonate leads to a higher neonatal blood volume, whichy ma cause a higher incidence of severe neonatal jaundice (NNJ) related to polycythaemia. However, the higher neonatal blood volume has also been linked to many benefits, including decreases in the number of blood transfusions, intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) and necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) in preterm neonates. In light of these beneficial effects, our Obstetric and Paediatrics service leads the change of delayed umbilical cord clamping (DCC) after thorough evidence review. Objectives (1)‐ To provide evidence‐based recommendation on time of cord clamping in premature neonates; and (2) to assess the effects of DCC for neonates from 30 to 35 weeks 6 days of gestation age. Methodology A working group including paediatricians, obstetricians and midwives, has been set up since July 2013 to study the feasibility and refinement of a safe and effective practice for DCC Singleton vaginal births from 30 to 35 + 6 weeks of gestation age are assessed for DCC. -

Beyond Survival

2nd Edition 525 Twenty-third St. N.W., Washington, D.C. 20037 Tel: 202.974.3000 Fax: 202.974.3724 www.paho.org/alimentacioninfantil Beyond survival: Integrated delivery care practices for long-term maternal and infant nutrition, health and development Beyond survival: integrated delivery care practices for long-term maternal and infant nutrition, health and development 2nd Edition PAHO HQ Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ********************************************************************************************************* Pan American Health Organization. Beyond survival: integrated delivery care practices for long-term maternal and infant nutrition, health and development. 2. ed. Washington, DC : PAHO, 2013. 1. Infant, Newborn. 2. Infant Care. 3. Infant Nutrition. 4. Child Development. 5. Delivery, Obstetric. I. Title. ISBN 978-92-75-11783-5 (NLM classification: WS 420) The Pan American Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or trans- late its publications, in part or in full. Applications and inquiries should be addressed to the Department of Knowledge Management and Communications (KMC), Pan American Health Organization, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. ([email protected]). The Family Health, Gender, and Life Course will be glad to provide the latest information on any changes made to the text, plans for new editions, and reprints and translations already available. Please contact Dr. Chessa Lutter at [email protected] or go to www.paho.org/alimentacioninfantil. © Pan American Health Organization, 2013. -

April 2017 a Newborn with Amniotic Band

NEONATOLOGY TODAY News and Information for BC/BE Neonatologists and Perinatologists Volume 12 / Issue 4 April 2017 A Newborn with Amniotic Band Table of Contents Syndrome By Kelechi Ikeri, MD; Surendra Gupta, MD; Case Report A Newborn with Amniotic Alexander Rodriguez, MD Band Syndrome A large-for-gestational-age full-term baby was delivered vaginally to a thirty-six--year-old By Kelechi Ikeri, MD; Surendra Introduction Gravida 4 female with one previous molar Gupta, MD; Alexander Rodriguez, pregnancy. She was an early registrant at the MD Amniotic Band Syndrome (ABS) has been prenatal clinic, was fully immunized and took Page 1 described clinically as rupture of amnion, only prenatal vitamins and iron in pregnancy. followed by encircling of developing structures She had no illnesses in pregnancy and denied A Comparison Between by strands of amnion. These may vary from alcohol or illicit drug use. There was no history constricting bands to limb reduction defects. C-Reactive Protein and of maternal trauma. Multiple etiologies may cause this single Immature to Total Neutrophil defect that produces a pattern of congenital Quad screening done showed an increased Count Ratio in the Early abnormalities. Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis risk of having a baby with Trisomy 18 (>1:10), but was negative for Down Syndrome and By Mary Grace S. Tan, MD; Hao The estimated incidence of ABS ranges from open neural tube defects. Subsequent Ying, PhD; Woei Bing Poon, 1:1200 to 1:15,000 live births1 and 1:70 2 amniocentesis results were unremarkable. MRCPCH, FAMS; Selina Ho, stillbirths. Serial Ultrasounds, however, revealed a MRCPCH, FAMS fetus with clubbing of the foot, and possible Page 8 We report a case of a newborn with abnormal bone deformity. -

Mortality Perinatal Subset, 2013

ICD-10 Mortality Perinatal Subset (2013) Subset of alphabetical index to diseases and nature of injury for use with perinatal conditions (P00-P96) Conditions arising in the perinatal period Note - Conditions arising in the perinatal period, even though death or morbidity occurs later, should, as far as possible, be coded to chapter XVI, which takes precedence over chapters containing codes for diseases by their anatomical site. These exclude: Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities (Q00-Q99) Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases (E00-E99) Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes (S00-T99) Neoplasms (C00-D48) Tetanus neonatorum (A33 2a) A -ablatio, ablation - - placentae (see alsoAbruptio placentae) - - - affecting fetus or newborn P02.1 2a -abnormal, abnormality, abnormalities - see also Anomaly - - alphafetoprotein - - - maternal, affecting fetus or newborn P00.8 - - amnion, amniotic fluid - - - affecting fetus or newborn P02.9 - - anticoagulation - - - newborn (transient) P61.6 - - cervix NEC, maternal (acquired) (congenital), in pregnancy or childbirth - - - causing obstructed labor - - - - affecting fetus or newborn P03.1 - - chorion - - - affecting fetus or newborn P02.9 - - coagulation - - - newborn, transient P61.6 - - fetus, fetal 1 ICD-10 Mortality Perinatal Subset (2013) - - - causing disproportion - - - - affecting fetus or newborn P03.1 - - forces of labor - - - affecting fetus or newborn P03.6 - - labor NEC - - - affecting fetus or newborn P03.6 - - membranes -

Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping

Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping It is the position of the American College of Nurse-Midwives that • Delayed cord clamping should be the standard of care in all birth settings for term and preterm newborns. In situations requiring resuscitation, umbilical cord milking may be of benefit when delayed cord clamping is not feasible, particularly for the preterm newborn. • Delayed cord clamping results in a placental transfusion of blood into the newborn that facilitates transition to extrauterine life by increasing birth weight, blood volume, and hemoglobin concentration, thereby increasing infant iron stores at 6 months of age.1,2 • For term newborns, delaying the clamping of the cord for 5 minutes if the newborn is placed skin-to-skin or 2 minutes with the newborn at or below the level of the introitus ensures the greatest benefit.3 • Delayed cord clamping does not increase the risk of developing tachypnea, clinical jaundice, or symptomatic polycythemia.1-3 • For preterm newborns, the benefits of delaying cord clamping for 30 to 60 seconds include a significant reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage and a reduced need for blood transfusion.4-7 • When a tight nuchal cord is present, delayed cord clamping can be accomplished with the use of the somersault maneuver rather than clamping and cutting the cord prior to birth of the newborn’s body.8 • In the event that early or immediate clamping is necessary for resuscitation or cesarean delivery, milking the cord may benefit preterm and term newborns.3,9,10 • Delayed cord clamping has not been associated with an increase in maternal hemorrhage and should not delay the administration of oxytocic drugs to the mother as needed.2,11,12 8403 Colesville Road, Suite 1550, Silver Spring, MD 20910-6374 240.485.1800 fax: 240.485.1818 www.midwife.org • The practice of delayed cord clamping should not affect a provider’s ability to manage the delivery of the placenta.11,13 Background Clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord after birth is one of the oldest interventions in the birth process. -

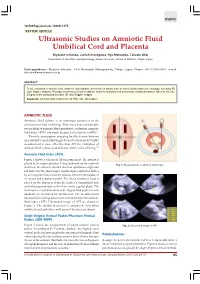

Ultrasonic Studies on Amniotic Fluid Umbilical Cord and Placenta

DSJUOG 10.5005/jp-journals-10009-1179 REVIEW ARTICLE Ultrasonic Studies on Amniotic Fluid, Umbilical Cord and Placenta Ultrasonic Studies on Amniotic Fluid Umbilical Cord and Placenta Kiyotake Ichizuka, Junichi Hasegawa, Ryu Matsuoka, Takashi Okai Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Showa University, School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan Correspondence: Kiyotake Ichizuka, 1-5-8 Hatanodai Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo, Japan, Phone: +81-3-3784-8551, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Detail evaluation of amniotic fluid, umbilical cord and placenta has been obtained by means of ultrasound new technology, including 3D color Doppler imaging. This paper summarizes fetal membrane anatomy and disorders using many ultrasound images taken by not only 2D gray scale ultrasound but also 3D color Doppler images. Keywords: Amniotic fluid, Umbilical cord, Placenta, 3D Doppler. AMNIOTIC FLUID Amniotic fluid volume is an important parameter in the assessment of fetal well-being. There have been considerable two methods of amniotic fluid quantitative evaluation, amniotic fluid index (AFI)1 and single deepest vertical pocket (SDP).2 Recently, some papers comparing the effectiveness between AFI and SDP reported that single deepest vertical pocket (SDP) measurement is more effective than AFI for evaluation of amniotic fluid volume as an indicator of the fetal well-being.3,4 Amniotic Fluid Index (AFI) Figure 1 shows a schema of AFI measurement. The patient is placed in the supine position. Using landmark on the maternal Fig. 1: Measurement of amniotic fluid index abdomen, the uterus is divided into four quadrants—right and left halves by the linear nigra, and the upper and lower halves by an imaginary line across the midway between the fundus of the uterus and symphysis pubis.