Policy & Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPUAP2020 Virual Abstract Book.Qxp Sestava 1

EPUAP VIRTUAL MEETING 24 September 2020 www.epuap.org ABSTRACT BOOK PROGRAMME OVERVIEW Time zone Thursday | 24 September 2020 CET Track A Track B Track C 09:00 - 09:15 Opening by Dimitri Beeckman 09:15 - 10:30 Session 1A: Medical device related pressure injuries; Session 1B: Prophylactic dressings; Chair: Jane Nixon Chair: Peter Worsley 09:15 - 09:35 Prevention and management of device related pressure ulcers: Reflecting Effectiveness of two silicone dressings for sacral and heel pressure ulcer on a decade of improvement and challenges to be addressed; prevention in 475 high risk intensive care patientss; Janet Cuddigan, United States Elisabeth Hahnel, Germany 09:35 - 09:55 Evaluating performance of medical devices in minimising risk of soft tissue Silicone adhesive multilayer foam dressings as adjuvant prophylactic damage; Dan Bader, United Kingdom therapy to prevent hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: a nationwide multicentre randomised open label parallel group medical device trial; Dimitri Beeckman, Belgium 09:55 - 10:15 Clinical perspectives on preventing device related pressure ulcers and the Systematic review prophylactic dressings for heel pressure ulcers; new International Consensus; Paulo Alves, Portugal Clare Greenwood, United Kingdom 10:15 - 10:30 Q&A Q&A 10:30 - 10:45 Short break 10:45 - 12:00 Session 2A: PPE and pressure injuries; Chair: Carina Baath Session 2B: Prone positioning - patient perspective and staff perspective; Chair: Maarit Ahtiala 10:45 - 11:05 The problem of facial injury using PPE in the general care setting; -

Download File

Number 54 September 2017 THE VETERAN THE NEW VTTA CHAMPIONS James McKenzie, enjoying the morning sun Don McLean & Mark Ledbetter battle through after a wet night - 24 Hour Champion the rain - 24 Hour Tandem Champions Richard Bideau clinched the 12 Hour Championship with 312.101 miles (+107.571), having already taken the 100 Mile with 3:38:40 (+1:13:52) All images courtesy of Kimroy Katja Rietdorf’s 258.508 miles earned her Lynne Biddulph - 100 Mile 1st woman on std & 1st woman, club team and group team in club team; 12 Hour 2ⁿd woman on std & club the 12 Hour Championship team; 24 Hour 3rd o/all on std, 1st woman on std, group team, club team 2 National Association for the 40 years old and over racing cyclist NATIONAL EXECUTIVE 2017/18 President Carole Gandy (Kent) 01622 762837 : [email protected] Honorary Life Vice President Keith Robbins Vice Presidents Mrs D Maher E A Green Chairman Andrew Simpkins (Midlands) 18 Richmond Close, Hollywood, Birmingham, B47 5QD 07767 835004 : [email protected] Treasurer National Secretary Mary Corbett (Wessex) Rachael Elliott 28 The Meadows 6 Pindar Place Lyndhurst, Hampshire, SO43 7EL Newbury, RG14 2RR 07837 551768 [email protected] 07931 722817 [email protected] Records Secretary Geoff Perry (London & Home Counties) Membership Secretary 8 The Meadway Merv Player (East Anglian) Loughton, Milton Keynes, MK5 8AN 18 New Close 01908 200680 Knebworth, Herts, SG3 6NU [email protected] 01438 814154 [email protected] Editor & Advertising Secretary Mike Penrice (Yorkshire) -

Download June's Parish Magazine

Welcome to your JUNE Digital Magazine We are now welcoming you to the third digital online magazine, and we are in danger of saying it’s beginning to be normal to be doing this. We do hope that this will be the last online only version of Mayfield Church and Village news and if restrictions continue to ease next month’s magazine (July) could well see us back at the printers and distributing real magazines to our 270 plus subscribers of which a significant minority have no internet access so can’t download this very magazine, However, our online magazine has proved to be a bit of a hit gaining more and more readers with each issue. Our April Magazine the first, was downloaded 256 and our second magazine May has risen to 312 downloads. Recognising that there are existing readers who cannot download the magazine it means we have gained 50 or more readers. The online edition allows us to publish many more photos and in colour, simply impossible with the cost of printing. However the printed magazine carries adverts and is by subscription both of which provides much needed funds for the church. The Future So, we are debating exactly what we do in the future. We will be printing the magazine and if you like what you see and do not subscribe already then do contact us as editors to ensure you always get a copy. To do that you can contact Joyce Beeson Email: [email protected] Tel. 346959 or Stephen Dunn Email: [email protected] Tel. -

University of Minnesota

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ;UafCH CommcNccment 1950 NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 16 AT EIGHT O'CLOCK Unillersitll 0/ jUinnesota THE BOARD OF REGENTS Dr. James Lewis Morrill, President Mr. William T. Middlebrook, Secretary Mr. Julius A. Schmahl, Treasurer The Honorable Fred B. Snyder, Minneapolis First Vice President and Chairman The Honorable Ray J. Quinlivan, St. Cloud Second Vice President The Honorable James F. Bell, Minneapolis The Honorable Daniel C. Gainey, Owatonna The Honorable Richard L. Griggs, Duluth The Honorable J. S. Jones, St. Paul The Honorable George W. Lawson, St. Paul The Honorable Albert J. Lobb, Rochester The Honorable E. E. Novak, New Prague The Honorable A. J. Olson, Renville The Honorable Herman F. Skyberg, Fisher The Honorable Sheldon V. Wood, Minneapolis As a courtesy to those attending functions, and out of respect for the character of the build· ing, be it resolved by the Board of Regents that there be printed in the programs of all functions held in the Cyrus Northrop Memorial Auditorium a request that smoking be confined to the outer lobby on the main floor, to the gallery lobbies, and to the lounge rooms. ~ltisls VOllf UniVefsilv The University of Minnesota: "FOUNDED IN THE FAITH THAT MEN ARE ENNOBLED BY UNDERSTANDING, DEDICATED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF LEARNrNG AND THE SEARCH FOR TRUTH, DEVOTED TO THE INSTRUCTION OF YOUTH AND THE WELFARE OF THE STATE"-this is your University. CHARTERED in February, 1851, by the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Min nesota, the Univ~rsi~ of Minnesota 'YiIl soon c~le~rate its on~ hu?dr~dth ~irthday. -

Download File

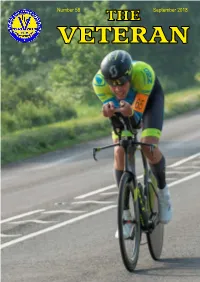

Number 58 THE September 2018 VETERAN 1 The Born to Bike women took the Club Team Rachael Mellor (Holmfirth Championship - Lynne Biddulph, Katja Reitdorf CC) indulges in some multi- and Susan Semple tasking NATIONAL 100 MILES CHAMPIONSHIP Gethin Butler (Preston Whs) looking determined Richard Bideau (Pendle Forest CC) on his way to 7th overall and a Group Team retained his 100 mile crown medal for North Lancs & Lakes Championship images courtesy of Front cover - Keith Murray (Drag2Zero & North Group) cruised to a championship bronze medal 2 National Association for the 40 years old and over racing cyclist NATIONAL EXECUTIVE 2018/19 President Carole Gandy (Kent) 01622 762837 : [email protected] Honorary Life Vice President Keith Robbins Vice Presidents Mrs D Maher E A Green Chairman Andrew Simpkins (Midlands) 18 Richmond Close, Hollywood, Birmingham, B47 5QD 07767 835004 : [email protected] Treasurer National Secretary Mary Corbett (Wessex) Rachael Elliott (London & Home Counties) 28 The Meadows 6 Pindar Place Lyndhurst, Hampshire, SO43 7EL Newbury, RG14 2RR 07837 551768 07931 722817 [email protected] [email protected] Records Secretary Membership Secretary Geoff Perry (London & Home Counties) Merv Player (East Anglian) 8 The Meadway 18 New Close Loughton, Milton Keynes, MK5 8AN Knebworth, Herts, SG3 6NU 07808 839811 01438 814154 [email protected] [email protected] Editor & Advertising Secretary Awards Secretary Mike Penrice (Yorkshire) Ian Greenstreet (London & Home Count) Tawnylands, South -

November 29, 2002 Vol

Inside Archbishop Buechlein . 4, 5 Editorial . 4 Question Corner . 15 The Sunday & Daily Readings. 15 Serving the CChurchCriterion in Centralr andi Southert n Indianae Since 1960rion www.archindy.org November 29, 2002 Vol. XXXXII, No. 9 50¢ Holy Land violence increases while war looms with Iraq WASHINGTON (CNS)—Violence in who are experiencing difficult moments The mother of 13-year- the Holy Land brought fresh condemna- of great suffering.” old Israeli Hodaya tions and prayers for peace, while groups A focus of the congregation’s meeting Asraf, who was killed in the United States and Europe continued was strengthening the Church’s pastoral in a Palestinian suicide their protests against a potential U.S.-led outreach, a process particularly difficult CNS photo from Reuters bomb attack, weeps war against Iraq. in the Middle East and other areas where during the girl’s funeral Pope John Paul II entrusted prayers for Christians are fleeing violence, discrimi- in Jerusalem on peace in the Middle East to the interces- nation and economic stagnation. Nov. 21. The bomber sion of Blessed John XXIII. That same focus lead a group of killed 11 people and The pope said the Holy Land and other British pilgrims to visit holy sites in injured 29 when he regions of the Middle East are “caught up Jerusalem and the West Bank in mid- blew himself up on a in a dangerous cycle which seems November. crowded commuter humanly unstoppable. May God make “Our presence here is to show support bus carrying, among this vortex of violence stop,” the pope of the Holy Land in these difficult times. -

An Exploration of the Use of Devices for the Prevention of Heel Pressure Ulcers in Secondary Care: a Realist Evaluation

An exploration of the use of devices for the prevention of heel pressure ulcers in secondary care: A realist evaluation Clare Elizabeth Greenwood Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Healthcare July 2020 II Intellectual property and publication statements The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own, except work which has formed part of jointly authored publications. The contribution of the candidate and the supervisors to this work has been explicitly indicated below. The candidate confirms that appropriate credit has been given within the thesis where reference has been made to the work of others. Chapter 3 GREENWOOD, C. E., NELSON, E. A., NIXON, J. & MCGINNIS, E. 2014. Pressure‐ relieving devices for preventing heel pressure ulcers. The Cochrane Library. (Withdrawn 2017 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011013.pub2) GREENWOOD, C., NIXON, J., NELSON, E. & MCGINNIS, E. 2019. Comparative effectiveness of medical devices for the prevention of heel pressure ulcers: a systematic review CRD42019152949. PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews [Online]. GREENWOOD, C. E., NELSON, E. A., NIXON, J., VARGAS-PALACIOSM, A., & MCGINNIS, E. 2020 Comparative effectiveness of heel-specific medical devices for the prevention of heel pressure ulcers: a systematic review. Submitted to BMC Systematic Reviews My own contributions, fully and explicitly indicated in the thesis, have been conception of the systematic review, lead on protocol -

April 4, 2003 Vol

Inside Archbishop Buechlein . 4, 5 Editorial . 4 Question Corner . 15 The Sunday & Daily Readings. 15 Serving the CChurchCriterion in Centralr andi Southert n Indianae Since 1960rion www.archindy.org April 4, 2003 Vol. XXXXII, No. 25 75¢ Pope says Iraqi war must not tur n into ‘religious catastrophe’ VATICAN CITY (CNS)—As the toll at the loss of life on both sides, including “War must never be allowed to divide of death and destruction mounted during four U.S. soldiers killed by an Iraqi suicide world religions. I encourage you to take the second week of war in Iraq, Pope bomber at a military checkpoint. this unsettling moment as an occasion to John Paul II repeatedly prayed for peace Speaking at a noon blessing from his work together, as brothers committed to CNS photo from Reuters and said the conflict must not be allowed apartment window above St. Peter’s peace, with your own people, with those to become a “religious catastrophe.” Square on March 30, the pope said the of other religious beliefs, and with all The pope, who strongly opposed an world was experiencing a moment in men and women of good will in order to attack on Iraq, made the comments as which “painful armed conflicts are threat- ensure understanding, cooperation and photos of civilian victims in Iraq pro- ening humanity’s hope in a better future.” solidarity,” he said. voked sadness and indignation in much of He offered a special prayer to Mary for “Let us not permit a human tragedy the world, especially in Muslim countries. -

Updates from Our National Committee and Branches

APRIL 2016 www.medsin.org ISSUE #1 [email protected] UPDATES FROM OUR NATIONAL COMMITTEE AND BRANCHES Join our current national committee members, and branches on a tour through some fantastic Medsin successes and adventures! ALUMNI AFFILIATES GHC Bristol! Find out what some From tours to Spotlights are on of our alumni have training, fundraising the sustainable been up to after to campaigns, hear development their Medsin days! their stories! goals...and some individuals! IFMSA MARCH MEETING 2016 - MALTA From policy proposals to trainings, inspirations to beaches, meet our delegates for this March's meeting, and what they've been up to during a trip to Malta! The ADVOCATE 1 CONTENTS MAIN A Message from the National Director, 4 Contact Us, 3 National Working groups Updates, 24 - 26 Love, Medsin, 28 - 29 Support Us, 33 FEATURE - p5 IFMSA March Meeting, 5 - 6 Sustainable Development: Our Roles in the Goals, 6 Infectious Idea: St George's Epidermic Simulation, 7 Medsin's Response to Gobal Surgery, 8 The Biggest Challenge in Global health, 9 -10 UPDATES FROM THE NATIONAL COMMITTEE - p12 Secretary - Matt Quinn, 13 - 14 Communications - Yue Guan, 14 Policy & Advocacy Director - Lotte Elton, 15 Updates from Affiliates - Alex Peterson, 16 - 17 REGIONAL & BRANCHES - p18 Midlands - Laura Myers, 18 Southwest - Laurence Wright, 18 Northern - Clare Greenwood, 18 Branches - Various, 20 - 23 Branch Spotlights -- UCL, 20 -- Cardiff, 21 16 -- Bristol, 22 -- Bart's, 23 The Advocate is a bi-annual ALUMNI CORNER - p30 e-magazine of Medsin - a student network and registered charity Natalie May, Joel Burton, Elly Pilavachi, Johnny tackling global and local health Currie, Beth Thomas, Karthick Selvakumar.